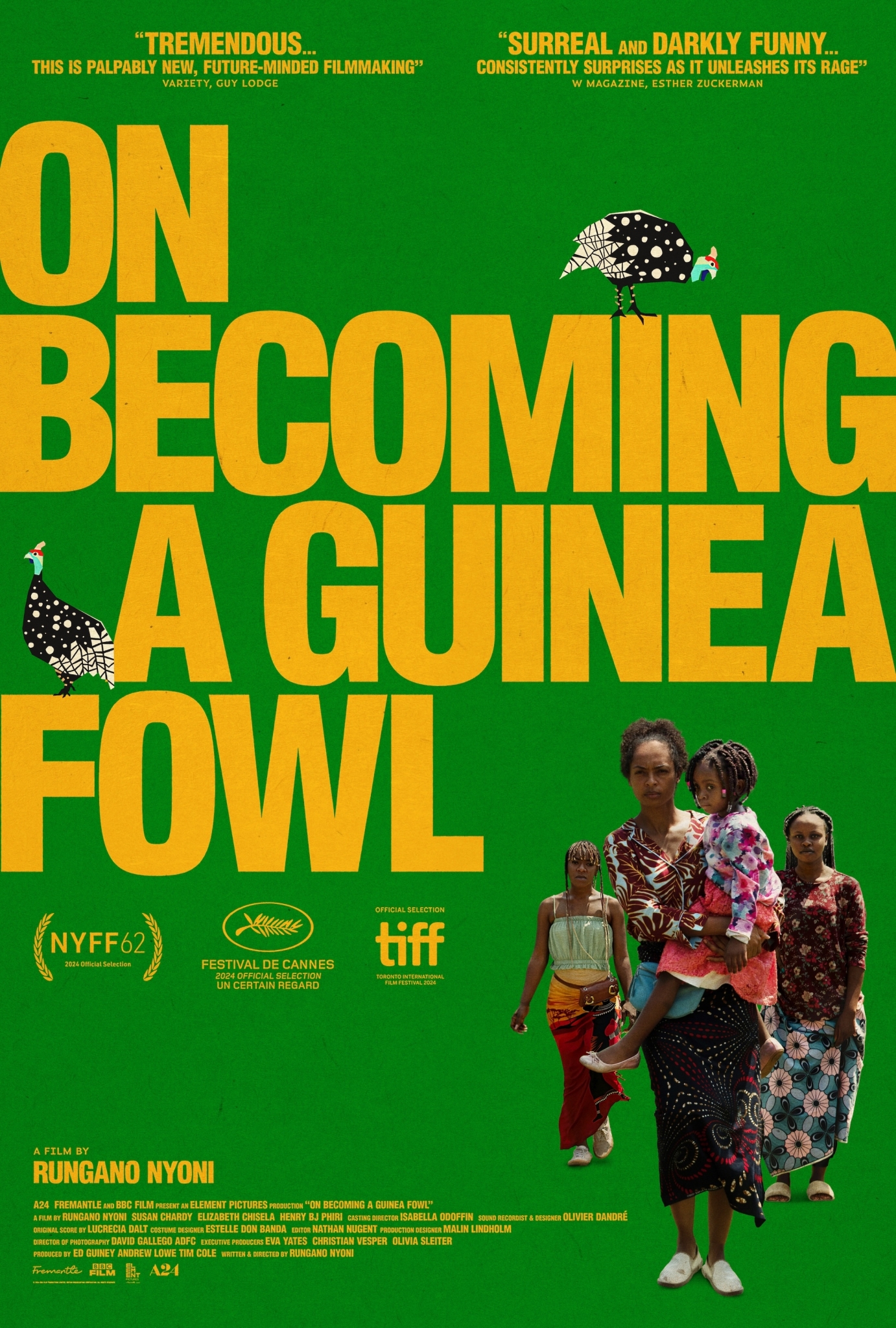

Rungano Nyoni discsusses the origins and inspirations of her second feature, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, which took home the prize for Best Film in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes Film Festival earlier this year.

“Film is about making things tangible, right? Like how do you deal with your past? Why do you stumble across it on a dark road?” The Zambian-Welsh director Rungano Nyoni is talking to me about the opening sequence of her second feature On Becoming a Guinea Fowl. Shula (Susan Chardy), recently back in town, is driving back from a fancy dress party, when, just down the road from a brothel, she encounters a corpse in the empty street. It is Uncle Fred, her mother’s brother who sexually abused her—and other female family members—as a child. After sitting for several moments, Her cousin, Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela), arrives, banging at the window. Shula is reluctant to let her in.

Set in middle class Zambia, where Nyoni is based, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl explores the inexpressibility of trauma, the performativity of grief and societal hypocrisies. Shula’s female elders are shown as a collective body of ecstatic mourners, whilst Shula, Nsansa and her other younger cousin Bupe resort, respectively, to repressed silence, inebriation and suicide attempts. Fred’s young wife, meanwhile, is accused of being a bad wife, and is ostracized by the community. On Becoming a Guinea Fowl’s central metaphor is a reference to a TV show Shula watched as a child, perhaps just before or after the assault by her uncle. This oblique memory presents us with the titular guinea fowl, an animal which provides a metaphor of transformation. “Guinea fowls can escape a hunting dog,” says Nyoni. “When [they] come together they can escape.”

Whilst the three young women’s ability to really heal seems remote, and Fred’s wife’s prospects seem even bleaker, with its moments of magical realism (so subtle they are more uncanny than dream-like) and moments of pitch black comedy, Nyoni finds other forms of release in the filmic medium. A Rabbit’s Foot spoke to Nyoni about animal metaphors, mourning, and finding inspiration from Federico Fellini.

Kitty Grady: Can you tell me about the starting point for On Becoming a Guinea Fowl? Was there a germ for the idea?

Rungano Nyoni: It’s difficult to say, I have a different answer every time. I’d forgotten but when I screened the film in Cannes, my producer of my first film told me, that I’d always wanted to tell the story of a girl who had experienced sexual abuse, and that I Am Not a Witch had this element in it. So she said she was happy that I actually finally got to tell the story and I had totally forgotten about that. She had actually advised me not to include it in that as it took away from the main story and maybe that deserves to be its own film.

KG: I was interested in the central animal metaphor of the guinea fowl. Was the television show you reference a real thing or memory? And why was this animal metaphor something you wanted to follow?

RN: The guinea fowl came in lots of different forms. It’s a Bemba saying about guinea fowls. It isn’t about sounding the alarm [as it is in the film], it’s that guinea fowls can escape a hunting dog, or something like this. But then I felt that it was too earnest somehow. I have to find the saying, but it’s something like, when guinea fowls come together, they can escape a hunting dog, meaning, you have to work in collaboration, even if you’re small and weak and too fragile to escape beasts. If we work together things will work out. So that was the idea, but it felt earnest so I decided to change it to a kid’s show. And when I found out more about guinea fowls, I was like, oh yeah that’s kind of the same thing, guinea fowls do have this way about them and they sound the alarm.

KG: I love the opening scene, where we have Shula in this kind of futuristic guinea fowl costume.

RN: [Laughs]. It’s a Missy Elliot costume! No one knows the reference and it makes me feel so old!

KG: Really?!

RN: Yes! Look it up, it’s a Missy Elliot costume from ‘The Rain’. People wear it for Halloween. But I guess it’s an age thing. It’s 90s hip hop. Videos didn’t come out very often so it’s sort of ingrained in my head. I’m like oh, she’s wearing fancy dress. I know, she’ll go dressed as Missy Elliot. But you don’t have to know the reference, actually. It’s good that people see it as this futuristic, funny costume.

KG: Yeah, well I was going to say I found it interesting you have this futuristic look at the beginning when it’s a film about addressing the past. She’s driving along, and it’s sort of about how trauma stops you in your tracks and sends you backwards.

RN: Yeah, it’s a good way to put it. Film is about making things tangible, right? Like how do you deal with your past? Why do you stumble across it on a dark black road? Trauma is minding your business and then there’s a body lying next to you and you’ve been avoiding it all this time, and you’ve got no choice but not to avoid it.

KG: Could you talk about how you use space in the film. I was struck by the use of confined spaces—the car or the kitchen cupboard.

RN: Yeah that was all deliberate. You have to find a way of trapping her. You either trap her with a camera—I was thinking of ways to express what she feels like. That’s why most of the film is in the dark, by the way. It wasn’t meant to be like that. The lighting was meant to come on and off, but when I was filming it, people were asking ‘is this a lights on day, or a lights off day?’. I was like just keep them off. I just started feeling really dark and moody I guess. I was trying to find ways of confining her and not having a still camera, because my cameras are always still. In the end, we got a dolly but it was too cumbersome. So it ends up being stillness on top of stillness. You can use the camera to confine them. The pantry was something from real life that I wanted to use. We were very much trapping her in the car, too. That’s why the end is how it is. It has to be something completely different to what we see. So, it’s not only light, but it’s in an open space. If I could have had the film in one location, I would have. But it didn’t work out like that and I just kept on expanding it.

Image courtesy A24

KG: Were there any film references you had in mind while making this?

RN: It’s going to sound like it has nothing to do with the film. It was—what’s his name? La Dolce Vita. Fellini. Someone, when they watched this they said it was like Fellini. But I’d only seen one or two of his films. But then he also combines professional and non-actors. He’s interested in faces. There’s an old-fashionedness to his camera that I really like. I like things that are obvious. If you didn’t understand what was happening, you could understand just through the image. There are some films that are so abstract. I don’t like abstraction in the camera. Like if you’re reading a storybook. Fellini films like this, and he uses a lot of surrealism which I’m a fan of. And his films just go everywhere, they are meandering. But his [films] are meandering in a good way. I still haven’t got the art of meandering. I would love to meander more.

KG: I thought the surrealist elements you handled very subtly. There is a magical element to it. But did you ever think about pushing it further and making it more mad?

RN: I would love to. I feel like I was too earthy. Because they’re not really surreal enough. They’re more like, as you say, magical realism rather than surreal. I think I was taking it a little bit too literally, because I was literally logging down my actual dreams. But I’d love to push that even further. Fellini does that so well. Not for the sake of it. So I have meaning or feeling. And you’re just transported somewhere else.

KG: I loved the use of water—did that come from a dream?

RN: Yes, it was a very specific dream, which, I don’t think we had enough budget to shoot. Water literally means being overcome with emotions that you can’t deal with. I was having these water dreams when I was going to funerals and I began to write them down.

KG: With Shula’s performance and character, she’s so constrained, and you almost want to shake her to make her let out some emotion. What sort of things were you saying in her ear?

RN: Susan is not like her character at all. It was a lot of work for her to go against herself. She’s an open book and really generous. My family and friends have said that with Shula I’ve basically made myself. They say, this is you. I’m like, really? I have done that subconsciously. I was writing other films and there’s always this talk of agency. People don’t want to make films unless women have agency. But in reality, that is something that’s really hard to have for yourself. You can have agency in some aspects of your life, but in others you become a little girl. Lots of people couldn’t understand that. Why can’t she do something? Why can’t she say something? It’s very difficult to explain in a culture that values silence and complicity and all this stuff.

KG: The sense of silence and secrecy is so heavy. We never have a moment where the wrongs are righted.

RN: It’s definitely a reflection of how I feel about real life. It’s very difficult to right those wrongs. It’s not as easy as saying your truth and then everyone is on board and it’s having to live with the consequences. People comment on the silence. But she said it when she was young. Everybody knows what he’s like, yet it still continues. How do you deal with that?

KG: We see these very particular performances of grief, which on the one hand feel performative, but on the other hand those rituals are culturally important. What do you think about this tension?

RN: I find funerals absurd. There’s a certain way you have to breathe. The women are expected to cry. And if you’re an outsider you’re thinking what kind of funeral is this. But when you’re in it, it’s very important, because it’s trying to tell you to let it out, don’t keep it in. But in the story, I love these people and I find it difficult. Imagine if you didn’t like the person at all. You’d feel disjointed from reality. You’d have to disassociate yourself from the whole thing. But I love the outpouring of grief, when you love someone. I’ve been to different funerals where everyone is sniffing and repressed. If I had to choose one I’d choose the one where you are screaming.

KG: The film is set in Zambia. But it’s a British and Irish co-production. Then it’s being distributed by A24. On the one hand it’s very culturally specific, but then also universal in terms of its message as well as it’s production and distribution. I was wondering how you define the film’s nationality?

RN: Nationality is complicated. Because in film you have to pick sides. For me it is a very Zambian film, because the language is so specific to Zambia. But, I think it’s trying to marry these different cultures because, inevitably, the people that hold the purse strings have to understand the film also. With co-productions you get a certain type of film. Ireland, they understood it actually, this culture of mourning wasn’t a foreign thing to them. People exotifying it are the worst, oohing and aahing. I only think about the audience in terms of do you understand what I’m trying to say? Do you understand the gesture I am trying to make? The frustration comes when you think you are filtering your ideas through the ideas that other people have from your culture. I feel this about a lot of international films. If they’re made as a co-production, it’s usually a version of a film that [everyone] understands and feels universal.

KG: What is your hope for the film of how the film will be received?

RN: I don’t know how I want this to be received. I don’t even know why I’m doing this. It just felt like something I needed to express at a moment in time. It’s hard. I always come out of films feeling really depleted and I ask the same question. Maybe next year I will have the answer. When you’re still feeling the ripple effects of making a film, I always have this crisis of conscience of why am I doing this? Why is it so hard? There are a thousand films being made and lots of them sound way more interesting. This always worries people, because I say ‘nobody is going to watch this film’. It’s a funeral. It’s in the Bemba language. You aren’t going to take a day off and order some popcorn with it.

KG: But I don’t think that’s your responsibility. Not every film is made to be watched with popcorn!

RN: But then you have conversations where it is treated as such. Justine Triet said at her Palme D’Or acceptance speech that she’s lucky she got to discover herself as a filmmaker and worries about the next generation. I believe that as well because every film is treated like, if this isn’t a Marvel film, what are we doing here? Let’s just accept that nobody is going to watch it and do the boldest version of what we’re doing.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl is in UK cinemas from 6th December and in the USA from 7th March 2025