The director of Opus dishes on his debut feature, an A24 cult-horror starring Ayo Edibiri and John Malkovich.

There’s an image seared into the mind of Mark Anthony Green, the writer-director behind new A24 thriller Opus, that blurs the lines between that which is harmless and that which is terrifying. “There’s this Beatles fan.” The Kansas-City native tells me, describing the seed that would become his debut feature. “She’s at a Beatles concert, and she’s screaming. Losing her shit. I can see her face. And if you take the crowd out of it, it looks like she’s in danger. You put the crowd behind her, and she looks like she’s having the time of her life. Same image, same person, same exact expression.”

Opus, similarly, appears harmless at first glance. The film opens with an invitation: 90s pop icon Alfred Moretti (John Malkovich) has emerged from retirement with news of a new album, and a lucky few have been chosen to visit his private compound in Utah for a very exclusive sampler. Among them: a talk show host, a radio jockey, a social media influencer, and Ariel (Ayo Edibiri), an upstart at a major culture publication struggling to make a name for herself as a journalist. It becomes clear, as the retreat unfolds, that the idyllic commune run by Moretti is far more sinister and cult-like in nature than any of his special guests could have anticipated. “I wanted to explore something that on the surface seems unproblematic and not at all scary,” he continues. “Because that’s how they get you.”

It’s a by-product of Green’s far-reaching interests and ideas that Opus will be read differently by each person who sees it. Some will zone in on how he examines the dangerous role that tribalism plays in contemporary culture, while others might see the ideological conflict between Malkovich’s and Edibiri’s characters (artist and journalist, respectfully) as parallels to Green’s own journey from feature writer—at GQ, for thirteen years—to feature filmmaker. He maintains he’s a direct avatar for neither character, at least not by design, but admits that it does explain the authenticity with which he portrays the worlds they inhabit in Opus. “If you’re a basketball player and you watch White Men Can’t Jump, you’ll probably really focus on basketball. But White Men Can’t Jump isn’t about basketball. And Opus isn’t about journalism.”

In the same vein, Opus isn’t necessarily about music either, but it is music, nevertheless, that serves as the film’s electrical pulse. As much a music aficionado as he is a cinephile (he mentions taking inspiration from the great horrors of Japanese cinema while making Opus), it only makes sense for Green to open his film with Eddie Hazel’s brain-melting guitar solo on Funkadelic track ‘Maggot Brain’(itself the opener on the beloved album of the same name). “George Clinton [leader of Funkadelic] was the first black man that I ever saw with his hair coloured.” He explains. “That was the first time I had ever seen that. [Funkadelic] were pioneers of a certain taste that I reference throughout the film in ways that I don’t think anyone cares about but me [laughs].” He calls that phenomena ‘Black alt music auteurism’, to which he nods affectionately throughout the film, from a blink-and-you-miss-it Lenny Kravtiz cameo to recruiting dream-team producers Nile Rodgers and The Dream to write three original songs for Malkovich’s character in the movie, as well as executive produce the soundtrack. “I needed [Moretti’s music] to sound like a 90s pop star made a massive hit today… that’s the assignment I gave to Nile and Dream. They approached that with such intensity, and really nailed it.”

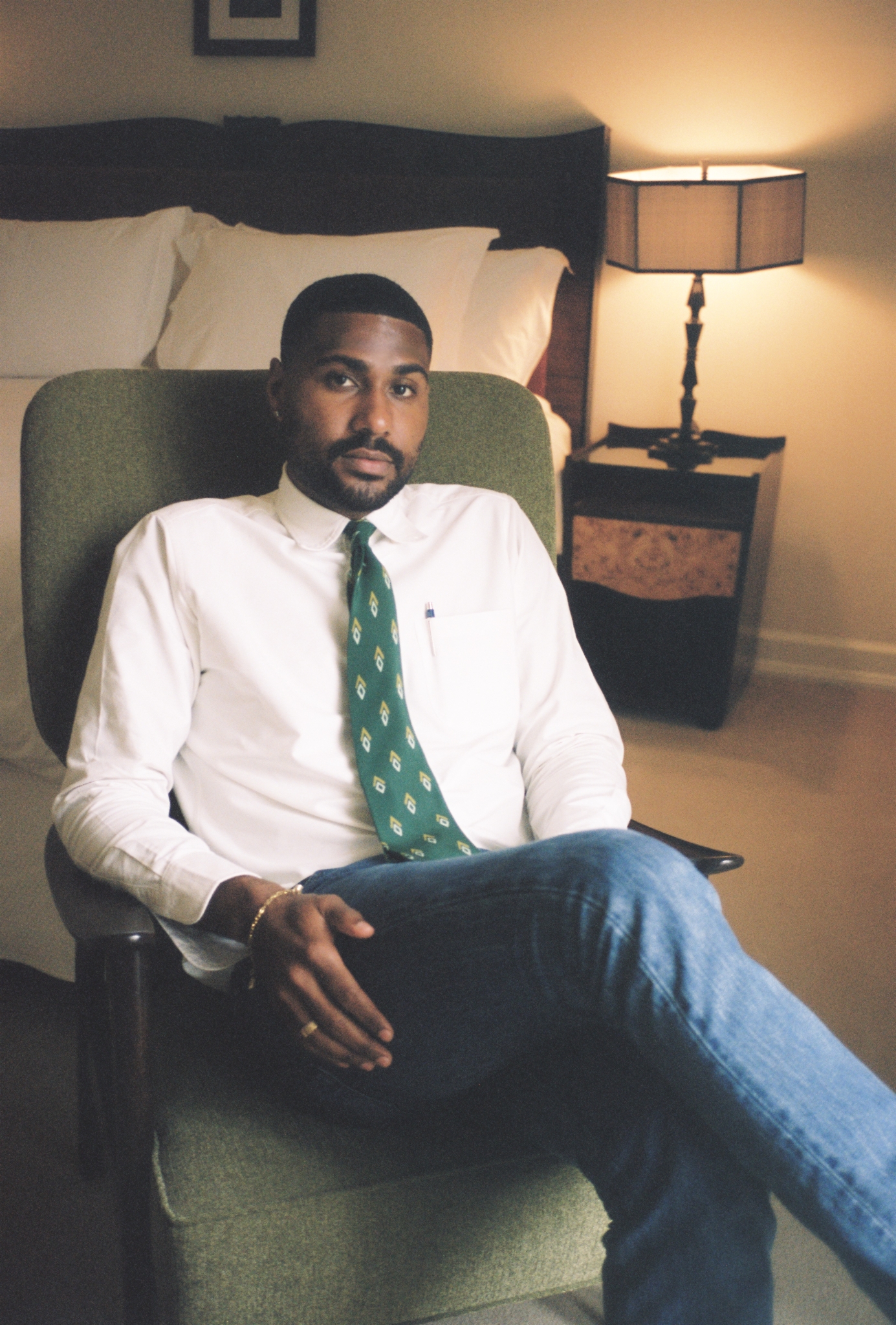

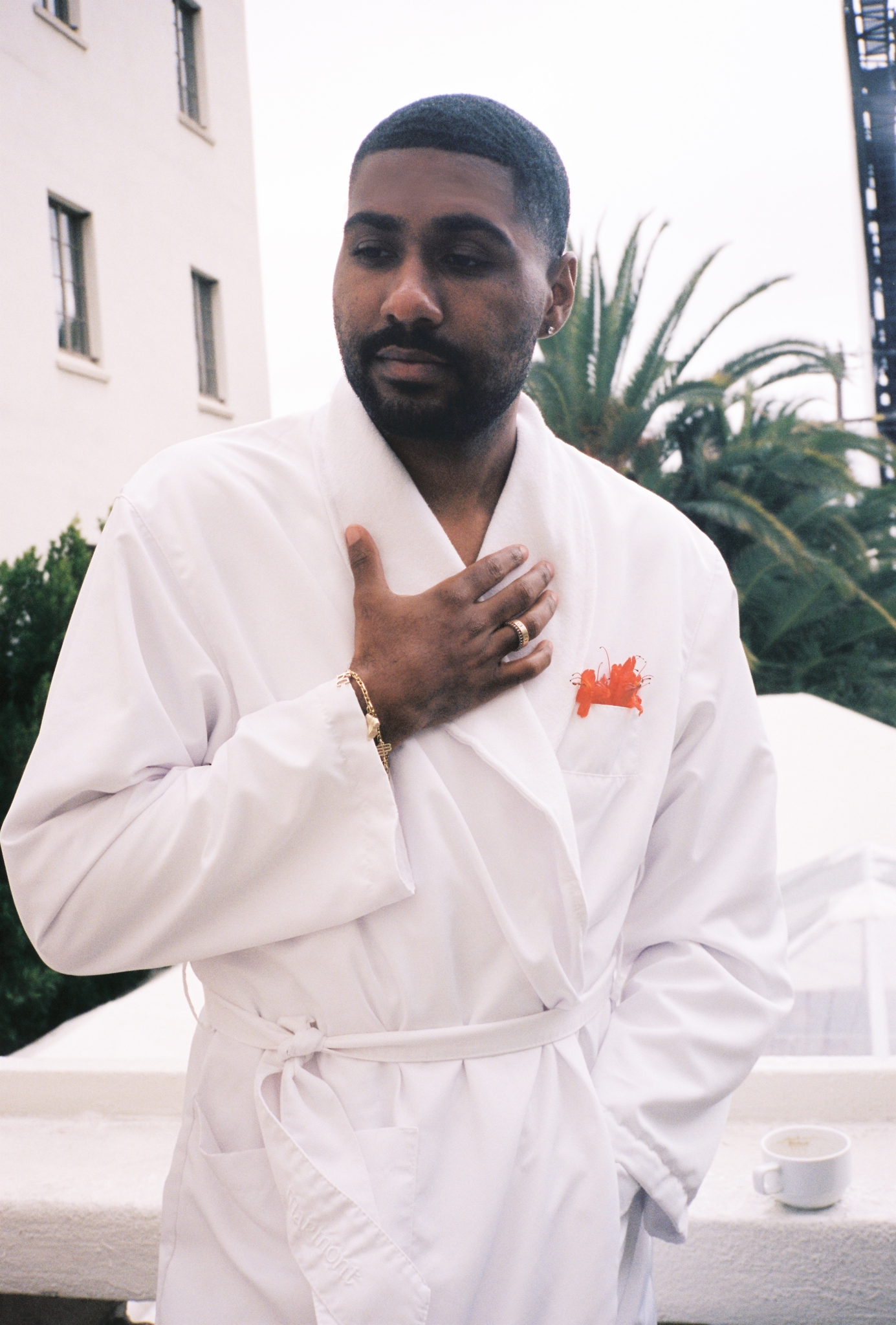

During an intimate shoot with A RABBIT’S FOOT creative director Fatima Khan at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, we sat down with Green to discuss Black alt music auteurism, making horror the Japanese way, and why he wanted Alfred Moretti’s sound to channel Michael Jackson’s Invincible.

Luke Georgiades: How does it feel for you to let go of this thing you’ve been working towards for several years? To have it not be yours in the sense that it was before.

Mark Anthony Green: I thought it would be hard for me. That it would be torturous. But there’s a little bit of relief. There’s the human relief of knowing I put everything into this film. One of the best feelings in the world is getting home after a long day of work and feeling deeply satisfied. I feel good because I know I gave it everything. And I’m excited for the next one. You don’t get to the next one if you’re holding on to this one. This is part of the process, and I’m trying to enjoy it.

LG: Watching the film, I knew as an audience member I was in safe hands when I heard the ‘Maggot Brain’ needle drop in the opening.

MAG: In the film there’s a throughline of, I haven’t quite coined it, but, like, ‘Black alt music auteurism’. The film starts with Funkadelic, whose heyday was before I was born. That song is older than me. But George Clinton was the first Black man that I ever saw with his hair coloured. That was the first time I had ever seen that. They’re pioneers of a certain taste that I reference throughout the film in ways that I don’t think anyone cares about but me [laughs]. Like Lenny Kravitz making a cameo. Like Nile Rodgers and The Dream producing the soundtrack. The closing credits song is a TV On The Radio track, which to me is like the younger generation Parliament of black indie, alt, thoughtful, cool as hell, stylish without chasing fashion trends—just that thing. It was fun sneaking that stuff into the movie.

LG: It sets the tone in an interesting, slightly subversive way.

MAG: I wanted to approach it differently than what a lot of traditional horror films do. I’m really inspired by Japanese horror films. Takeshi Miike is one of my favourite directors. The thing that you see a lot in those films is that they take their time. Playing ‘Maggot Brain’, in that style, with those visuals, it felt like settling everybody in. I’m trying to earn the audience’s attention.

LG: It’s true—films like Audition and Cure and Pulse are unsettlingly mundane for stretches of their runtime.

MAG: Some people are frustrated by that. But I see that restraint as a challenge—the challenge of not killing or kidnapping someone in the first five minutes of your horror movie. That unsettledness of not clearly broadcasting my intentions to the audience. That’s way more interesting as a theatrical experience to me. I get it’s frustrating for some, but, shit, that’s one of my favorite things about the film.

LG: How did you feel Nile Rodgers and The Dream’s creative brains worked differently?

MAG: They’re different, but they know exactly what part of themselves to offer up to the other. They have a great rapport. It’s easy to make the argument that Nile and The Dream are two of the most successful record producers in the history of humanity. If you look at the numbers and the impact of the songs they’ve made, the scale and impact of the work, it would be really hard to find five producers that have done more than those two. Both of those guys live in the studio. Dream can make six songs in a day. Nile makes a song every day. That’s the first thing he does when he wakes up in the morning. So for two people that talented to be willing to work with me, and do it for a fraction of what they usually get paid, just purely out of the spirit of creativity, is really cool.

Like any other sensitive creative, I want everyone to love me. I want everyone to love every word that I write, I want them to love every creative decision I make. I want that. But more than that desire is the want for your work to make them feel something, even if it’s anger or frustration.

Mark Anthony Green

LG: How did you want Moretti’s music to come across in the movie?

MAG: Remember that Michael Jackson album Invincible? The later one, it’s got that song ‘You Rock My World’. That song is incredible. ‘Butterflies’ is incredible. There’s one other song on there that’s good. But then the rest of the album doesn’t really work because Michael is trying to sound current. And he dates himself and dates the music because it’s so not him. It’s really hard to have someone whose prime was thirty years ago make music that at once feels very “now” but also very “then”. That’s the assignment I gave to Nile and Dream. I needed it to sound like a 90s pop star made a massive hit today. They approached that with such intensity, and really nailed it.

LG: I thought a lot about The Menu while watching Opus. I thought a lot about Blink Twice. Where do you think that obsession we have with the cult manifesting itself through celebrity or prestige is coming from?

MAG: I think power has always been ugly, but in my lifetime, I don’t know if it’s ever been this ugly. This bucktoothed. So I think a lot of artists across all mediums are observing this power imbalance, we internalise that and then put something out in the world that reflects it. Me and Zoe [Kravitz] and Mark [Mylod] have all made very different films, but it’s come from a shared feeling of being struck by this singular observation. It’s a bit like a smell. You know how a smell doesn’t really enter a room like a lightswitch? It creeps in and slowly fills the room. And this observation I have of how we treat one another is a thing that has gotten worse and more obvious as time has gone on. I started working on Opus six years ago and unfortunately it’s more relevant now, because the problem has gotten worse. At its most successful, Opus makes people ask that question: does tribalism still serve us?

LG: I know Ayo’s character isn’t necessarily an avatar for you, but I wonder if during your time as a journalist you ever witnessed a scenario as bizarre as some of what we see in this film?

MAG: There’s no direct parallel to any part of the film, but when I first started fleshing out the idea of Opus, I had this image of this Beatles fan. She’s at a Beatles concert, and she’s screaming. Losing her shit. I can see her face. And if you take the crowd out of it, it looks like she’s in danger. You put the crowd behind her, and she looks like she’s having the time of her life. Same image, same person, same exact expression. I wanted to explore something that on the surface seems unproblematic and not at all scary. Because that’s how they get you. If I tell you we’re going to share a loaf of bread, there’s no harm in that, right? If your favourite musician calls you and says, “hey, I love what you’re doing, we have this beautiful community, I’d love for you to come visit”, there’s nothing wrong with that phone call. But when you peel back the layers, it gets more and more fucked up, until you’re suddenly holding a soggy loaf of bread, and you don’t know how you got there. When I was researching cults, I kept asking myself, like, really, what is it? How does someone get so deep? It soon became apparent to me that it’s because the “invitation”, so to speak, was so above board, so enticing, that you just fall into it. I crafted some of the moments like that in the film because I assume that’s how it feels.

LG: Do you have any sympathy for a character like Moretti? Is there tragedy in his character?

MAG: I love that question. What do you think?

LG: It makes me think of Kanye, because he’s been in the news recently, and the complexity of him being deified throughout his career by fans, by himself and how that has affected him in the long term in various ways.

MAG: Hmm. Do I feel sympathy for Moretti? The honest answer is: no. But there is a point that he makes at the end of the film, like most good villains, that suggests that it isn’t all black and white. It’s about power, but not only about power. I can see that. My approach to achieving that point would be very different from his, whether people believe that or not. Some people think I’m him.

LG: John Malkovich is in a film directed by Robert Rodriguez that famously isn’t going to be released for a hundred years. It’s a very Moretti thing to do. Did that play into why you wrote the character for him?

MAG: [Laughs] I heard about that. With John, there are two hundred and fifty things like that. That’s just how the man lives. He wakes up in the most sincere way possible. He wakes up and he charges after a very interesting life. I recently said to a friend that people perceive him as this eccentric villain, and he is one percent as villainous as you think he is, but he is two million times more eccentric. He really is that guy. Working with him was the most fun, inspiring part of making this film. He trusted me 100%. He was the best partner I could have asked for.

“I’m proud of evoking a strong response. Like any other sensitive creative, I want everyone to love me. I want everyone to love every word that I write, I want them to love every creative decision I make. I want that. But more than that desire is the want for your work to make them feel something, even if it’s anger or frustration.”

Mark Anthony Green

LG: The movie is out now. It’ll be well received by some. Others may criticise it. What do you make of all that, as a former journalist and an artist?

MAG: It will be polarising. It’s safe to say that. I’m proud of evoking a strong response. Like any other sensitive creative, I want everyone to love me. I want everyone to love every word that I write, I want them to love every creative decision I make. I want that. But more than that desire is the want for your work to make them feel something, even if it’s anger or frustration.

LG: Did it ever feel like you were putting two sides of yourself against each other in that way?

It’s more an exploration of self. Your first question was how does it feel to give this movie away. Part of that process is letting people take the movie how they want to take it. The next step of this film’s life are audiences and critics watching it. So if you take Opus as a criticism of the media, it’s not my right to get in the way of that. If you were to ask me? Not only was that not my intention but it’s not how I read it. But as an artist you want the dialogue. If something isn’t provocative then there’s no conversation, and that would be the biggest bummer in the world to me. If the movie did two billion at the box office but people weren’t having the conversations they’ve been having after the film, I’d be happy about the money, because money’s cool, but I’d be bummed that the conversation wasn’t happening. So, yeah, I feel really good [laughs].

LG: Speaking of being provocative, tell me about your use of the grotesque in a few key scenes in this film.

MAG: It’s a very Korean and Japanese approach where It’s not like a slasher movie that’s gory all the time. I want to make people look away. It’s not intended as a crude exploration of how far we can push body horror and mutilation, but if you’re going to do it, then go all the way. That’s the Japanese lesson. Japanese horror goes all the way. I think it’s fun. It’s what makes this ride super fun so you engage with the ideas of the film. The medicine just goes down easier with a lot of honey.

Movement director: Andrew Georgiades

Videography: Matilda Montgomery

OPUS is in UK and US cinemas now.

Special thank you to Chateau Marmont, Los Angeles.