The director discusses making Hard Truths, the prospect of retirement, and why it’s important to keep fighting.

There isn’t another film in recent memory that will take a sledgehammer to your gut quite like Mike Leigh’s Hard Truths. It sneaks up on you: the movie’s first half is filled with laugh-out-loud moments, following stay-at-home wife and mother Patsy (Marianne Jean-Baptiste, on top form) as she goes about her days unleashing a barrage of bitter insults at her plumber husband Curtley (David Webber), introverted twenty-something son Moses (Twain Barrett), sister Chantelle (Michele Austin), and just about anyone, strangers included, who dares interact with her. But a sense of dread clings to Patsy’s shadow, and we find out about halfway through Hard Truth‘s runtime that the grief of losing her mother, with whom she had an up-and-down relationship, is at the root of her crotchety demeanour. It engulfs her—soon, it engulfs us too.

Despite Hard Truths being, without a doubt, one of the finest films of the year, featuring, without a doubt, one of the most staggering lead performances of the year, directed by, without a doubt, one of the most important voices in British cinema ever, it’s had a remarkably difficult time from the get-go. “It’s discouraging.” Leigh says, during our conversation in central London. “It took years to get this made.” In 2024, after a shoot plagued by delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the movie was rejected for consideration by both the Cannes and Venice film festivals—peculiarly, considering Leigh previously won Best Director at Cannes for Naked in 1993, and then the Palme d’Or itself only a few years later for Secrets & Lies (1996). As I write this, the Academy have just announced their nominations for the 2025 Oscars, without so much as a nod to Leigh, Hard Truths, nor any of its utterly fantastic cast (thankfully, the BAFTAs knew better, with the film and Jean-Baptiste being nominated for Outstanding British Film and Best Actress, respectively).

It’s true that Leigh’s approach to filmmaking might not scream pound signs to studios looking for a smash hit. “What I might pitch to investors…the fuckers…is: ‘can’t tell you anything about it, can’t discuss casting, and don’t interfere with it.’ The result of which is that nobody is interested.” It’s part of the beauty of the work, though, that the auteur makes little room for compromise or studio interference. It’s for that reason that he was able to pay homage to his son, Leo Leigh (also a filmmaker), during a standout moment in Hard Truths involving a biker funeral that offers no other explanation for its existence than the fact that it simply is. It’s because his filmmaking process begins, famously, not with a script, but a seed of a story that he gradually fleshes out over months of improvisational rehearsals with his actors, that Hard Truths captures Black-British dialect with more authenticity than just about any other white filmmaker could. It’s what makes Hard Truths a movie that, despite being largely omitted from the conversation, will age better than many of the films nominated for Best Picture this year.

The 81 year-old Leigh isn’t as mobile as he used to be, but it’s not uncommon here in London to spot him attending screenings at the likes of the BFI or the Curzon Soho, where I once stood behind him on a cold October afternoon as we patiently queued for a screening of Luca Guadagnino’s Bones & All. “It would be like a writer who doesn’t read books or an artist that doesn’t go to galleries,” he says. He remains a fervent champion of cinema—a fan of the medium and an advocate for the next generation of filmmakers, whose creative freedom he feels is suffocating in an industry dominated by studio box-ticking. While discussing his current struggle to secure financing for his next film, Leigh indirectly offers those same filmmakers a sentiment that they would be wise to keep note of: “It’s even more important now to make films because it’s so much harder to get them made. You need to keep fighting the fight.”

Below, Leigh discusses making Hard Truths, the prospect of retirement, and shutting up and getting the hell on with it.

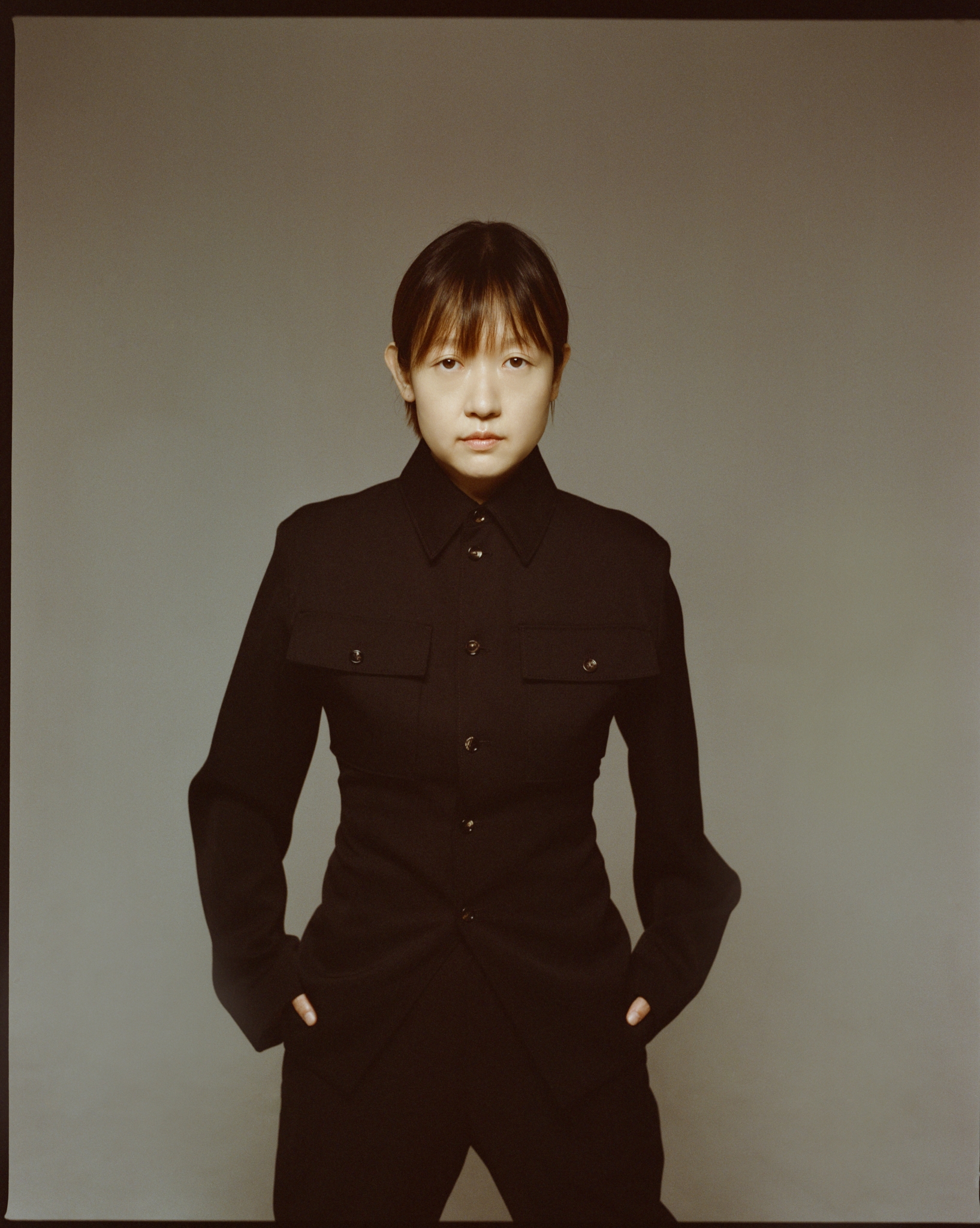

A still from Hard Truths (dir. Mike Leigh, 2024).

LG: Why was it important for you to return to contemporary London after 14 years?

ML: I’ve made contemporary films and I’ve made period films, I think the more important thing is whether it’s about people. For me, it’s about humanity, irrespective. I’ve made films about different sectors of society. I’ve made films about posh people, about working class people, I’ve made films in Northern Ireland about Catholics and Protestants, Republicans and Loyalists. I did a play in Australia about Greek Australians. I did a play at the National Theatre about Jews. For me, it’s about looking at people, and that includes 19th century people, and it includes 20th and 21st century people.

LG: Hard Truths is one of your shortest films.

ML: It’s a practical business. It’s a lower budget film, which means the canvas is smaller. With a bigger budget I might have had a more complex story so far that there would be more actors and locations, so I didn’t really plan it that way. I wouldn’t have wanted this film to be a bigger budget film—I would have wanted a bigger budget, and it therefore would have been a different film. I would like to have the same kind of budget we had for Peterloo, but to do a contemporary film, what I might pitch to investors—the fuckers—is: “can’t tell you anything about it, can’t discuss casting, and don’t interfere with it.” The result of which is that nobody is interested. Only when we said, “it’s about Gilbert and Sullivan, it’s about J.M. W Turner, it’s about the Peterloo massacre”, i.e. historical, were we able to get a bigger budget. I would have liked that kind of budget on this film, but it has nothing to do with the final product. Hard Truths is the film that it is, and I’m absolutely pleased with it. And so is everybody else. And so are you.

LG: Absolutely. You’ve mentioned that it’s become harder for you to get films funded. Does that ever discourage you from pursuing certain narratives?

ML: It’s discouraging. It took years to get this made, obviously the pandemic didn’t help. But, no, not at all. If it ever were to become impossible, then I’d say, “there you go.” I can always make stage plays. My number one passion is film. It’s even more important now to make films, because it’s so much harder to get them made. You need to keep fighting the fight.

LG: Quentin Tarantino has said that after 10 films he’s going to call it a day and quit while he’s ahead. You’re still making some of your best films at this point in your career. Does that thought of putting a full stop at the end of your career resonate with you?

ML: No, it doesn’t. However, and I don’t know how old Quentin is, but I’m 81 and disabled, so those are the issues. But even as we speak, I’m trying to raise the money for another film. Writers don’t stop writing, painters don’t stop painting, so why should filmmakers stop making films? Obviously, bless him, he’s got a whole different lifestyle than me, and probably you and me. I am a filmmaker. My job is to get the hell on with it, make films and shut up.

LG: There’s a moment in the film that really stood out to me: Patsy and her sister are visiting their mum’s grave and this biker gang drives through the cemetery. It felt like we were getting a glimpse into a different movie. Can you tell me about that moment?

ML: In a way, it was. My son, Leo Leigh, is a filmmaker and he made a feature last year called Sweet Sue. It’s about a middle-aged woman who goes to a biker’s funeral and has a relationship with this biker. So, as an homage to Leo Leigh, I decided to have a biker’s funeral in Hard Truths. That’s the genesis of it, but, of course, that’s the personal explanation.

But the great thing about film, although it should be true of all art in one way or another, is that it’s imagery, and the things that happen can be inexplicable, they don’t need a rational or intellectual explanation. That’s why so many films have fucked up by studio executives interfering and trying to rationalise everything. Fortunately, that doesn’t happen with my films, nobody interferes at all, so you can have something like that based entirely on instinct. That moment felt really right.

A still from Hard Truths (dir. Mike Leigh, 2024).

LG: Happy Go Lucky explores the inverse of Hard Truths in some ways.

ML: A few people have said that and it hadn’t occurred to me.

LG: I wonder what you think the common ground might be between Poppy (Sally Potter) and Patsy, though their attitudes to life are so different.

ML: I don’t really know the answer to that. It’s academic, that. They’re two quite different spirits, they don’t need commonality with each other. It certainly wouldn’t have occurred to me, other than the fact that I would certainly rather hang out with Poppy than this Pansy.

LG: I want to ask you about the moment where Curtley throws out Patsy’s flowers, seemingly unprovoked. I’ve enjoyed trying to unravel that moment since I saw the film.

ML: And I refuse to help you. It’s in the nature of the thing: to hand it over to you for you to speculate. I think the audience, in the nicest possible way, needs to do a bit of work. To analyse it for you psychologically, which will undoubtedly go into print, will fuck the experience up for any of your readers that are potential audiences of the film.

LG: What do you make of where we are now in terms of how highly valued television is by audiences, streamers and studios, considering for some time your art lived on the small screen during the early years of your career?

ML: The truth of the matter is, when we made our films for television, the BBC mostly, there was total freedom. Ken Loach, Stephen Frears. Play For Today. Each producer had four or five slots (i.e. films), and once you got a producer to agree to give you one of those slots, that was it. And they’d say, “we don’t know what you wanna do, but this is the budget, this is the deadline, now go away and make your film.” Nobody would interfere. That was it.

It isn’t like that now. I’ve been turned down twice by the BBC in the last eighteen months, because “we don’t know what we’re going to get,” as though I’m trying to con somebody. In fact, I’ve made twenty-eight films and over twenty plays, all on the same basis. You go to Netflix. It took them less than 5 minutes to say no. The mantra I hear is: “we respect what you do, we like what you do, but if we can’t screw it all up, then we’re not interested.” When we decided to make a film about the Peterloo massacre, which plainly would have to have a bigger budget, my producers went to Cannes to hustle for it, and on day 1 they met Ted Hope at Amazon. Amazon Studios were new on the film scene, wet behind the ears, and my producers told them “Mike Leigh wants to make a film about-” and they said, “great, you’re on!” They backed it immediately, they were totally supportive. It was fantastic. Now because they’ve grown up, and they’ve been around for a while, when we approach them with a movie they say, “not for us.”

I’m not worried for myself, because I can also go “Tarantino” and stop doing it. But I’m worried about younger filmmakers who are having a tough time having the freedom to do what they want to do and how they want to do it. They are constantly subject to box ticking. It’s iniquitous.

LG: Do you often look back on your films and put them in the context of the present day?

ML: I don’t really, no, without sounding pompous. A lot of people have claimed that obviously Hard Truths is a post-pandemic film. Is it? I don’t know what’s post-pandemic about it. Obviously you can speculate on how being holed up in that house might have an affect on Pansy, but she isn’t a function of that. If we made the film 20 years ago the issues would have been the same, because they’re universal. My films aren’t time specific, not really, though they’re rooted in 20th and 21st century life and culture. You don’t see many mobiles in my films. In fact, this film is the first time you see a sustained scene with a mobile in any of my films. Local details, you know?

Hard Truths is out in UK cinemas on 31st January. You can read our review of the film here.