The “high priestess of body horror” Julia Ducournau and Tahar Rahim discuss Alpha, an AIDs allegory, which despite its austere surfaces, contains deep messages about love, family and belonging.

Love may not be the word that comes to mind when thinking of director Julia Ducournau, high priestess of body horror and winner of the 2021 Palme d’Or for Titane. But “Love!” is what she says decisively, bringing her fist down on the table, when I ask her what her latest film Alpha is about.

Ducournau, 41, is graceful and self possessed. She looks you in the eye. She says what she thinks, and what she thinks she means. I am talking to her at Curzon’s headquarters in Soho, alongside her lead actor Tahar Rahim, 44—star of A Prophet, The Mauritian, and more recently, Hollywood titles such as Madame Web—who has a gentle presence and a smile quick to grace his lips. It’s their first time working together, but for both, it “didn’t feel like it”. As we talk, they laugh a lot and finish one another’s sentences. If 2016’s Raw used cannibalism as a visceral lens to explore a young girl’s appetite and coming of age and 2021’s Titane dissected gender and family through a woman who gets pregnant with a car, Alpha is a different monster entirely.

“Immediately, for me, I was using the grammar of [the horror] genre in order to create empathy and understanding and humanity, as opposed to creating unease, disgust, fear, as I’ve used in the past”, Ducournau explains.

Alpha is a difficult film to describe. On paper, it’s about Alpha (Mélissa Boros), a 13 year old girl from a Berber-French family who lives with her single mother (Golshifteh Farahani). They live amidst the chaos playing out on hospital wards and at her school regarding a contagious blood-borne virus. Alpha’s uncle Amin (Tahar Rahim) comes to stay, recovering from heroin addiction and—as later revealed—the virus.

But it’s also an abstract meditation on how it feels to grieve; how addiction turns loved ones into strangers and the tragic impossibility of “saving” someone from their fate. It’s about the tension between the old world of myth (here, it’s expressed through the invented “red winds”) and the contemporary one of science and modernity (Alpha’s mother is a doctor; many scenes take place in the neon-flashback of a hospital ward). Like Raw, it’s about the trauma we inherit, as well as hereditary dispositions. A striking scene shows Alpha—who may or may not be sick—and Amin, their bodies wildly convulsing in tandem as they sleep. The film captures the ambivalent and at times dehumanising feelings that I have felt in my own recovery from addiction, as well as the underwater state that I fell into when my dad died suddenly three years ago.

The virus in this world turns people into marble, a visual detail that is significant, Ducournau tells me. “Marble is a very noble material. And it’s a material that is also linked to sacredness, to a verticality, if you wish, because it’s used in churches, in cathedrals. This is what saints are sculpted out of”.

Ducournau continues, “to portray the lives and the deaths of people who have been treated like pariahs and marginals, and who have been shamed by an entire society, was a way to reclaim their dignity, to build a sacred monument to them”.

Love and fear are two sides of the same coin, because the moment you start loving someone, then you start fearing losing them.

Julia Ducournau

Rahim embodies this complexity, playing Amin as both a mischievous urchin and small, scared child trapped in a grown man’s body. A particular scene—a bustling and jovial family dinner at Eid—shows how alienated and invisible he is to those around him, even his own family. “Amin is not reduced to either his addiction or his affliction. Amin is a real person. He’s a brother. He’s an uncle. He’s both childlike and extremely wise at the same time,”Rahim tells me. He’s both completely chaotic and extremely balanced in other ways. And he’s a person who has loved, who still loves and who is loved. At no point for me was it about analysing or dissecting his addiction. All that I was interested in was just him” animated.

Rahim’s insistence on playing Amin as a complex character, not defined by his addiction or his disease, is a sentiment echoed by Ducournau. “I’m never shooting a close-up on a needle getting into a vein. That would have been like fetishisation. That would have been gross to me, to be honest”.

Then there are the similarities to the AIDS pandemic, which aren’t accidental; while writing the script, Ducournau reflected upon the way that, back then, “society mistreated people who were in need of care and abandoned them, both physically, medically, and morally more than anything.” In her film, she gets to subvert the cruelty of reality, as well as the well-worn trope of the sick, outcast and disabled, as monstrous. “I wanted people to immediately feel empathy and accept these patients not as others, not as foreigners, not as creatures”.

To enable him to physically inhabit Amin’s tortured subjectivity,Rahim lost 40lb, following a strictly supervised diet that stretched him like a “rubber band”. Losing weight, he said, helped him believe in the role, giving him a part of his character he could authentically embody. “You find a source of truth, and if there’s one thing that the camera never misses, it’s the truth”.

The film manages to avoid the trap of romanticising addiction or making Amin a cliche of the drug-addled-fuck-up.

“I wanted to show respect to the people I spent time with. And that was a conversation with Julia beforehand. Not just to depict him by his addiction, but as a human being who’s not seen by others. How that hurts. To show he has sort of a goofy kid energy”, he says. “The way she thought about the character was the most important thing for me, because I wanted to blend into her universe. I mean, I wouldn’t have played the role the same way if it was for, let’s say, Ken Loach.”

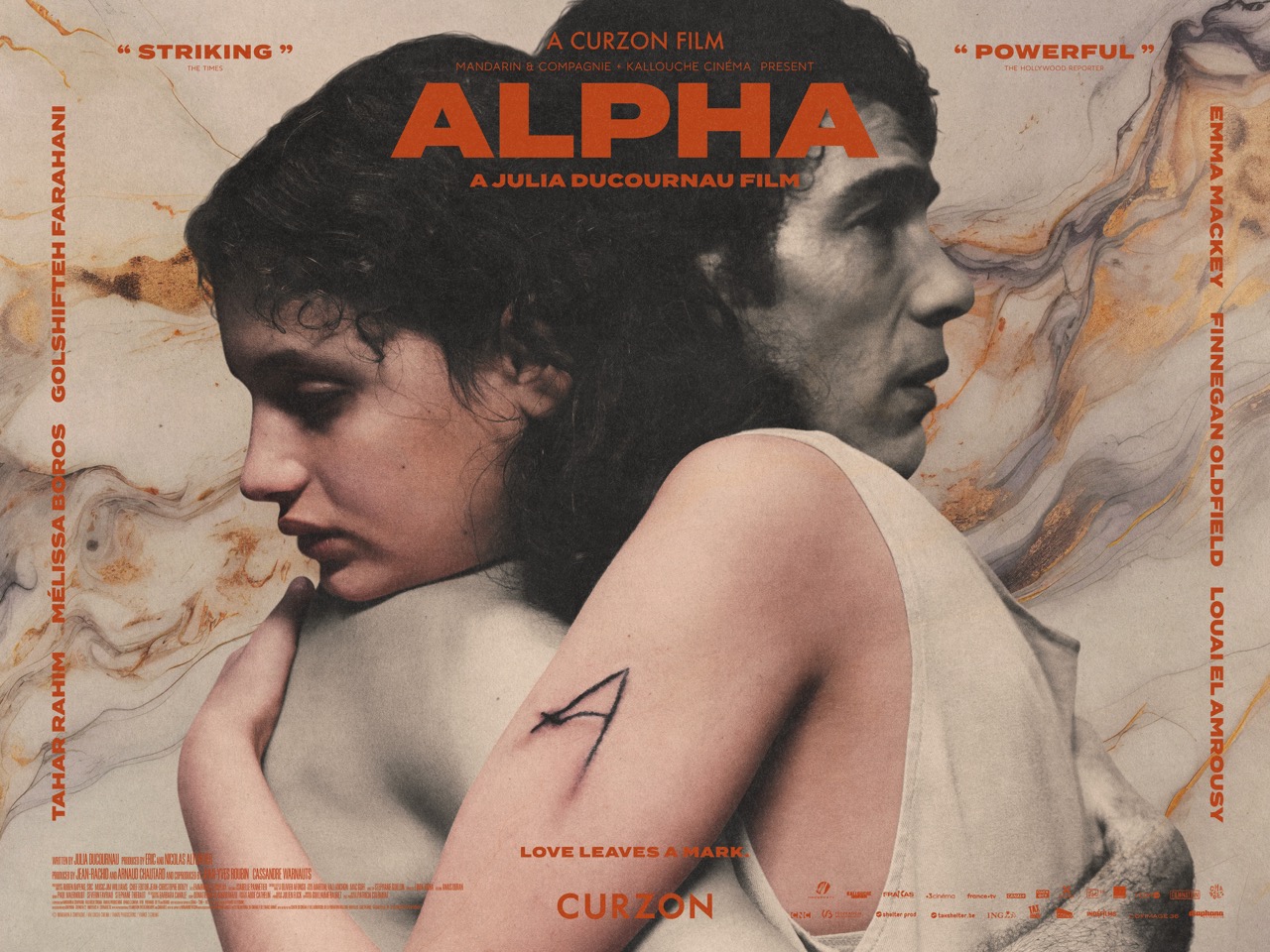

Poster for Alpha, directed by Julia Ducournau (2025)

Ducournau sees the film’s message as being, centrally, about the bonds of love, and how we have to detach from them in order to live our own life. As she tells me this, I can’t take my eyes away from her; it feels profound to be sat in this blindingly white windowless room, hearing Julia Ducournau’s treatise on love. “Love is a tricky thing because it implies something is taken for granted or completely denied, sometimes: love implies a form of responsibility.”

“Love means respecting the other one’s free will and their freedom. Even though it can become, at some point, an obstacle in the way you express or you feel your love,” continues Ducournau. “And obviously, love and fear are two sides of the same coin, because the moment you start loving someone, then you start to fear losing them. And this is a thin line that’s often overpassed, right?”.

We are speaking about Alpha and her mother, and Alpha’s mother and Amin, how she wants to rescue them, and the impossibility and frustration of this. As we talk about this, I feel Ducournau’s eyes boring into me, assuaging the red winds of my own grief and memories.

“Love drives people crazy, sometimes”, she laughs, in a final way, looking at Rahim. Our time is up. Later on, walking around the city, the conversation lingers inside my body for a while, like a pulse, faint beneath the skin, strange and restless.

Alpha is in cinemas now