John Pawson’s work may be synonymous with minimalism, but as one of Britain’s most respected architects, there’s more to his philosophy than simply spare-and-stripped-back. His interest in clarity; what is essential in the spaces we inhabit, the freedom for residents or visitors to breathe is a satisfying contrast to the Maximalist revival that has taken hold over the past few years.

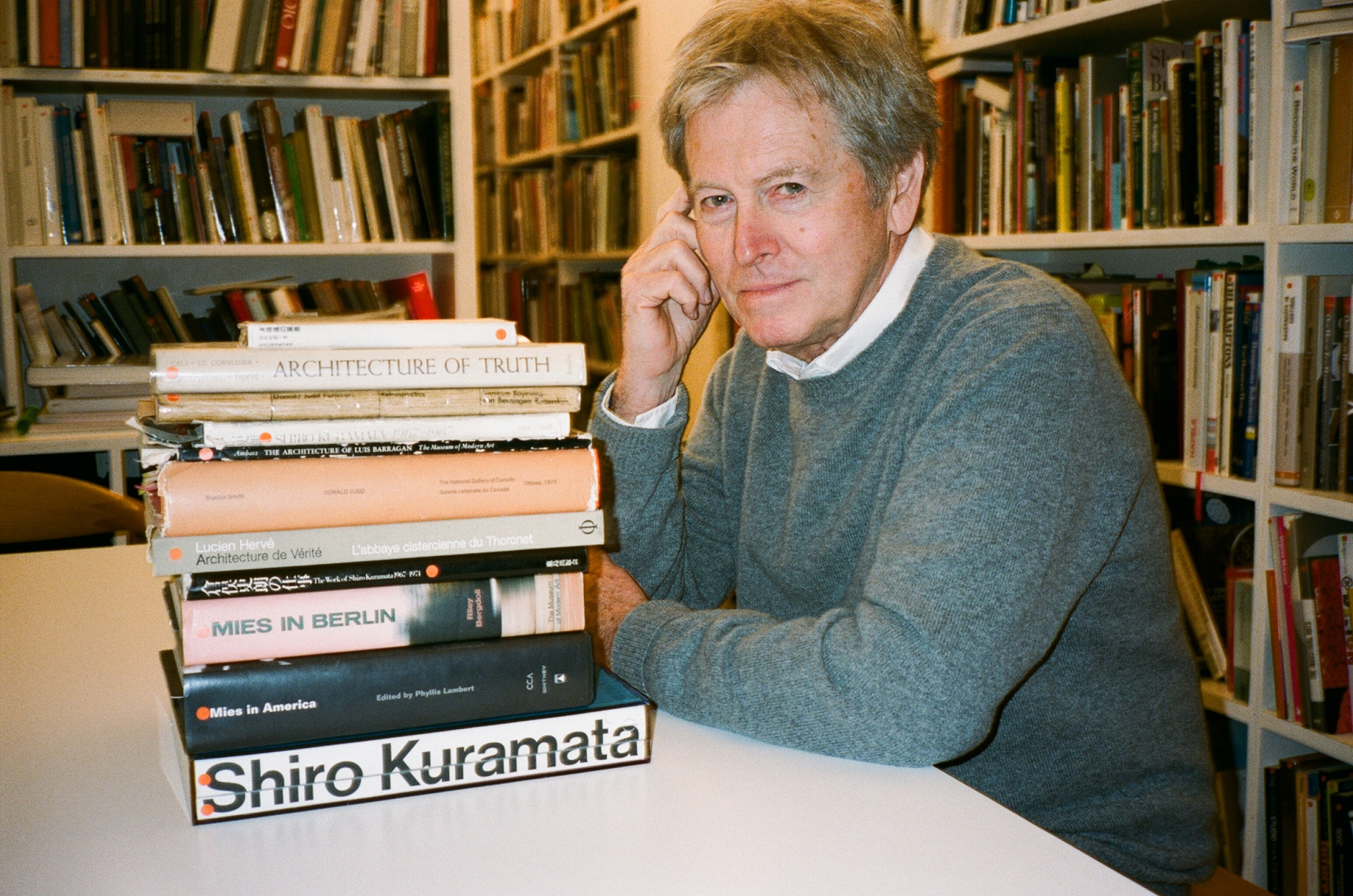

Born four years after WWII in Halifax, England, Pawson is also something of an outsider to the trade. Beginning his early career in textiles, he then emigrated from London to Tokyo in his mid-twenties to study with the Japanese architect Shiro Kuramata. Finding a touch of zen, he would return home and enrol in the National Architect’s Association, leaving in 1981 to begin his own independent practice that celebrated negative space, symmetry and light beauty.

In a suitably minimalist exchange, our creative director Fatima Khan questions the visionary designer on the philosophy behind his lifelong passion at Pawson’s King’s Cross studio.

Fatima Khan: You’ve of course always been closely linked to minimalism — I’m interested in where you think maximalism fits in, in a modern world increasingly leaning into minimalism.

John Pawson: Minimalism and maximalism are two threads that have run through history for centuries. Sometimes one appears much more dominant than the other and then this prominence switches over again. There will always be people who are instinctively drawn to maximalism, in the same way that minimalism represents everything that makes sense to me, aesthetically, visually and emotionally. I think that what shifts is the way we find to express these preferences, according to the priorities and preoccupations of our times.

FK: In his film Columbus, Japanese-American minimalist director Koganada suggests that architecture has the power to “heal”. Do you view the art form as having a spiritual quality to it? If so, how has it affected you in a spiritual way?

JP: Everything about a spatial environment — from the quality of its light, to its proportions, surfaces and atmosphere — has a profound impact on how we feel. When you walk into a space where all of these conditions are right, the sense of quiet exhilaration is immediate and immense — for some people the reaction is a literal exhalation, accompanied by a lowering of the shoulders, as tension is released. For me, this quality of ease and stillness has a spiritual dimension.

FK: What did you learn from your time studying the craft in Japan that you couldn’t have found anywhere else?

JP: During the years I was living in Japan in the 1970s, what struck me was the meticulous attention to details of construction and surface, alongside a reverence for materials, which at the time felt unparalleled.

FK: I read somewhere that Shiro Kuramata persuaded you to become an architect. What’s something that inspired or struck you about his style? What’s the best piece of advice he gave you?

JP: My first encounter with Kuramata was in an issue of the Italian architecture and design magazine, Domus. I was still in my teens and something inside me resonated with what I saw on those pages. Kuramata had a genius for turning ideas into physical realities, but the most important lessons he taught me during the time I spent hanging around his studio in Tokyo concerned the value of discipline and hard work and the need always to find the ‘sparks’. The best advice he ever gave me was to return to London from Japan and enrol at The Architectural Association School of Architecture.

FK: Your new show Mass opened in April in Tokyo. How do you find your work has been received differently in Japan than other places in the world?

JP: The reception is markedly different in Japan. There is real commitment in the people who come to see the work — a desire to immerse themselves in the encounter and to process the experience in a serious way.

FK: What was the most recent example where a personal life experience bled into your creative vision?

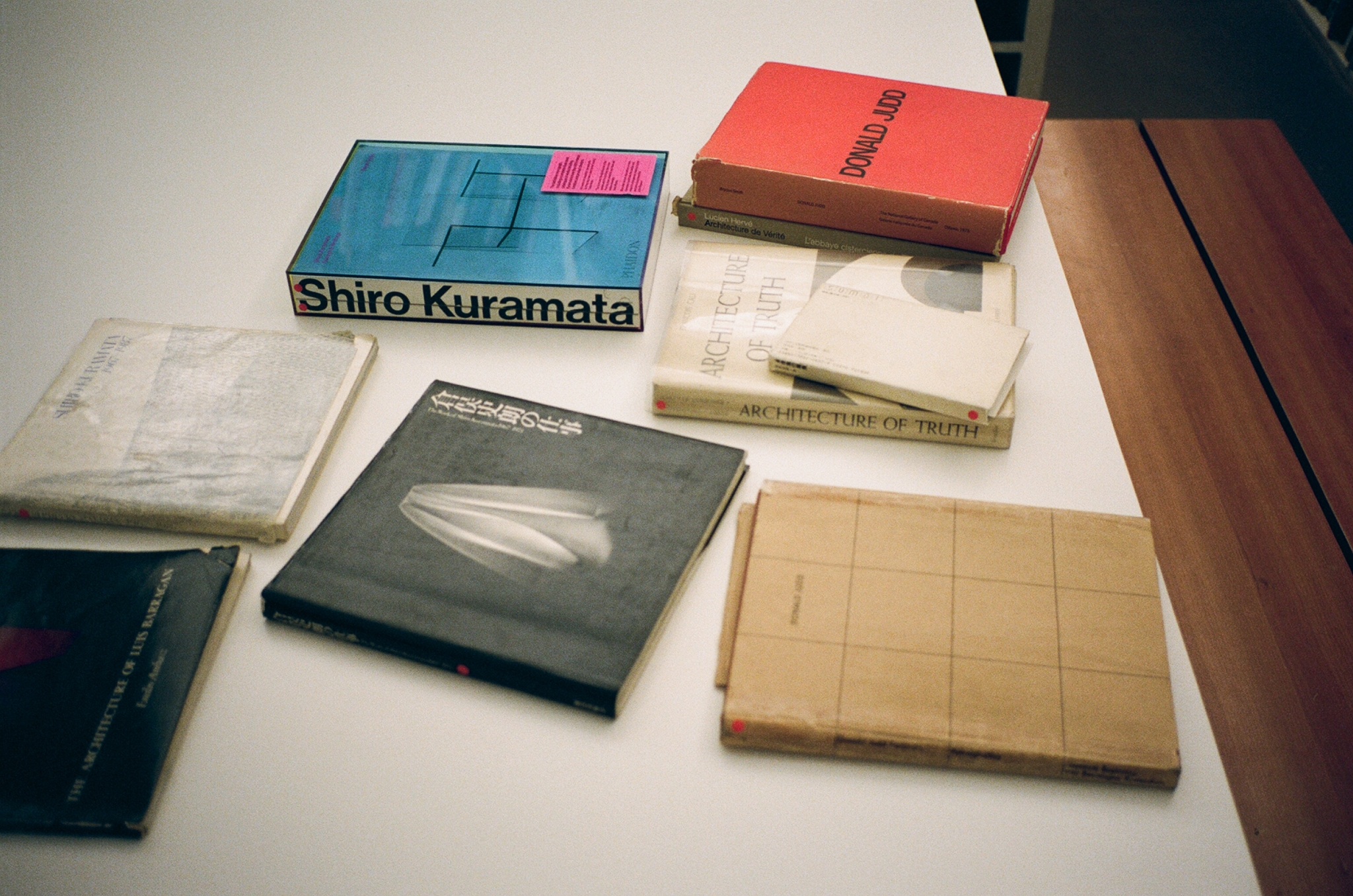

JP: There have been a number of personal life experiences — including the deaths of people important to me and encounters with a few extraordinary places, like Donald Judd’s work in Marfa, Texas — that have given pause and influenced my outlook, but it is my family that has always been the great continuum, driving my creative vision.

FK: What’s your favourite colour and what emotion does it bring to you?

JP: It was Herman Melville who described whiteness as ‘not so much a colour as the visible absence of colour’, but for me it is the richest of all colours, encompassing an infinity of shades and tones, all of them the perfect context for the play of light and shadow. In personal terms, it is a physical expression of emotional calm.

FK: Does the minimalistic aspect of your taste influence your experience with other art forms such as film or music?

JP: I am not someone who wants everything to conform to my own aesthetic preferences and I have always enjoyed a wide range of other art forms. When it comes to music, my elder son, Caius, is in the music business, which means that I am in the fortunate position of constantly encountering new music — and the people who make it.

FK: You’ve always been an avid traveller — where’s the last place you travelled that changed the way you think about your approach to architecture?

JP: I am frequently profoundly moved and excited by the places I visit, but I don’t think this necessarily translates into shifts in my approach to architecture. Looking back over the past decades, there have been many projects in many locations, but I can see the same thinking that shaped the first work I ever made, driving the most recent.