For decades, Jacques Audiard has refused to give in to what audiences and critics expect of him. He speaks to A Rabbit’s Foot about his work on Emilia Pérez, and why he still has faith in the experimental power of cinema.

Jacques Audiard is a filmmaker who defies categorisation. Born in Paris in 1952, he is a famous “anti-auteur” with a taste for crime stories, and a renegade who goes against what is expected of him by the critics. His 10th movie, Emilia Pérez, is the most dramatically different of them all: a musical set in the Mexican underworld and centred on a mob boss who transitions into a woman. It is moving and violent, but very unlike his most internationally known film A Prophet (2009). Yet, with Audiard’s reliable skills as a filmmaker, it is just as powerful. Emilia Pérez is now streaming on Netflix to great success, and took home the Jury Prize at Cannes, with its three lead stars (Zoe Saldaña, Karla Sofía Gascón, and Selena Gomez) jointly winning Best Actress. It had great success at the Golden Globes recently, too, winning (among other prizes) the Best Picture in the Musical and Comedy award.

That’s very impressive for a first-time musical director. But what does anyone expect from an artist who has always fearlessly confronted many mediums, stories, and languages, as a writer and a filmmaker. “I don’t like the word challenge,” Jacques Audiard insists, when we meet. “Let’s call them difficulties instead.” This sums up his entire approach: no complaining—just do it.

We are sitting together near London’s Whitehall, a stone’s throw from the Royal Courts of Justice and the Houses of Parliament. If there was a difficulty, he explains, when I ask him how he approached such an ambitious project, it “was to have everyone work as a collective, everyone together on the same project. And the key thing is to have us all communicate quickly.” But for all of his perceived regiment, Audiard’s collaborators, including his long-time costume designer Virginie Montel, tell me the opposite: “In his structure, he allows for complete creative expression. Working with Jacques is freeing.”

“I’m not as cynical as people think,” he tells me, fully self-aware. “Sure, there are difficulties when I’m making films that are unexpected, like Emilia Pérez. But they keep me curious and help me to explore new questions. And that is why I make cinema.”

Audiard—along with Leos Carax, Céline Sciamma, Olivier Assayas, Claire Denis, François Ozon, and Arnaud Desplechin—is one of France’s established storytellers. There have been critical highs abroad, but he has never reached the fame as a director that he enjoys at home. And in France, where the greats are never above the guillotine of scrutiny, journalists and commentators sometimes judge Audiard’s anti-conformity. In an article for Le Monde, Thomas Sotinel mentioned being present at a screening for A Prophet, where an approving critic grumbled: “I never liked Audiard, but this…” The critic probably wouldn’t approve of Emilia Pérez. Not that Audiard cares. “You cannot please everyone,” the filmmaker explains to me. “Nor should you want to.”

Emilia Pérez tells the story of a Mexican lawyer (Saldaña), who is offered an unusual job: to help a notorious cartel boss (Gascón) fulfil a desire to retire and transition into living as a woman—all to the backdrop of Clément Ducol’s musical score. While there are themes and throughlines that connect Emilia Pérez, you could mistake Audiard’s previous films for having been made by a different director. “Is this the same person who made the brutal Rust and Bone (2012)?” I thought, while being entertained during a scene in a Thai sex clinic. There’s violence in Emilia Pérez; Audiard has always been good at that (and especially at the transcendental kind), but if you’re looking for similarities across his oeuvre, you will be grasping at straws.

“I found the process absolutely exhilarating, and then I learned how to interact with certain professionals. Because I’m not in the music industry, I didn’t know how to speak to dancers or singers, so I had to learn how to communicate.”

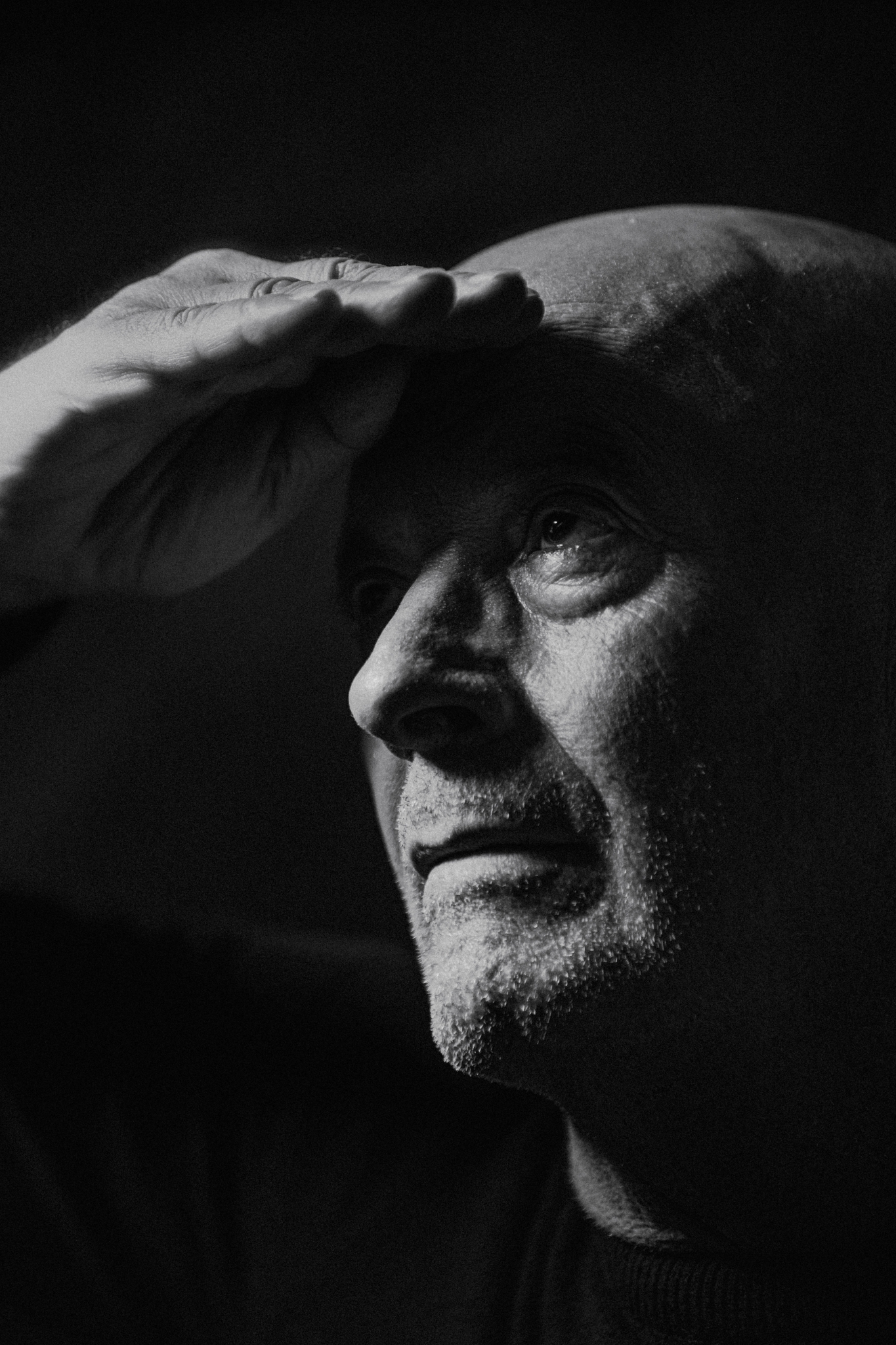

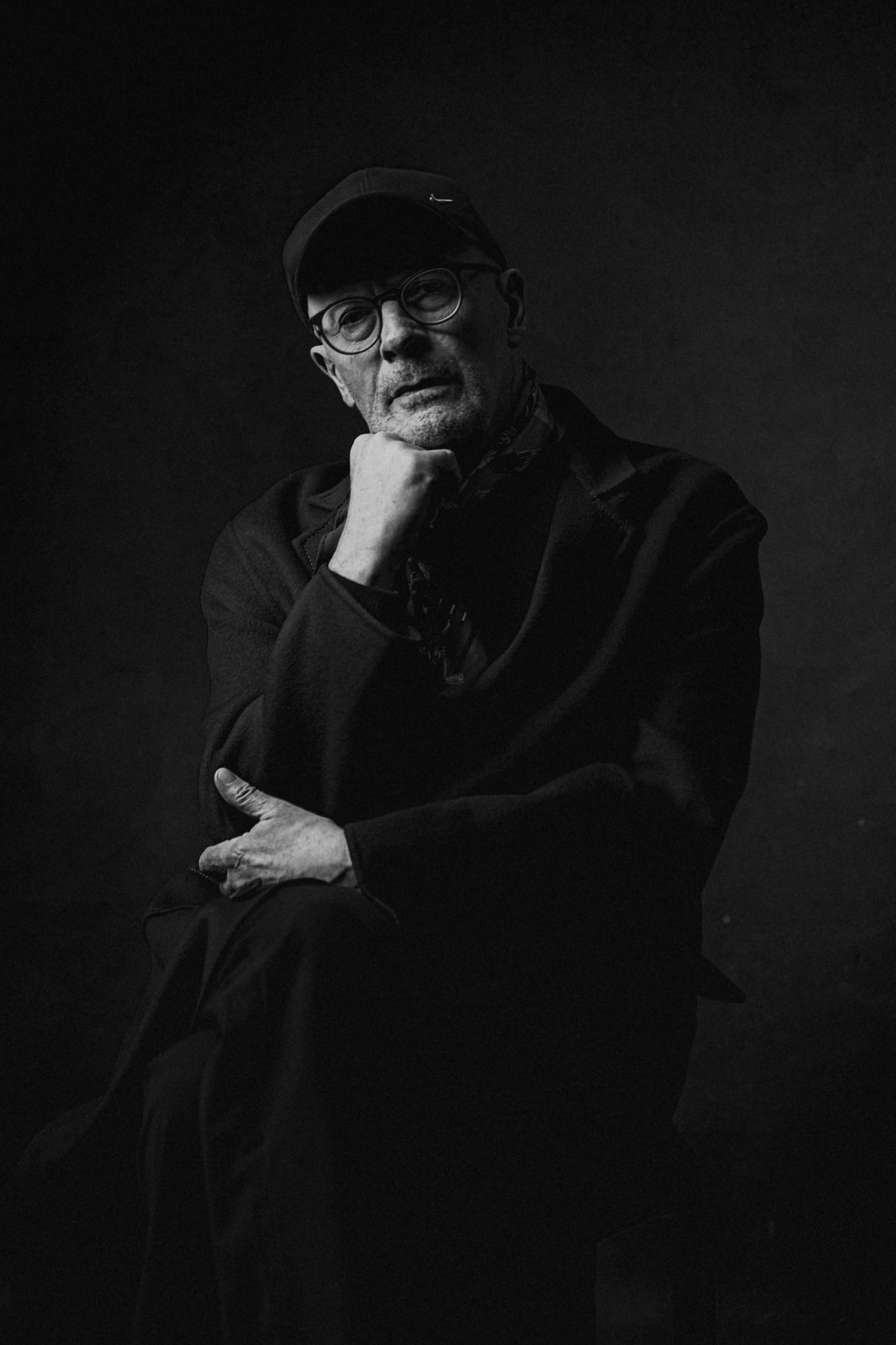

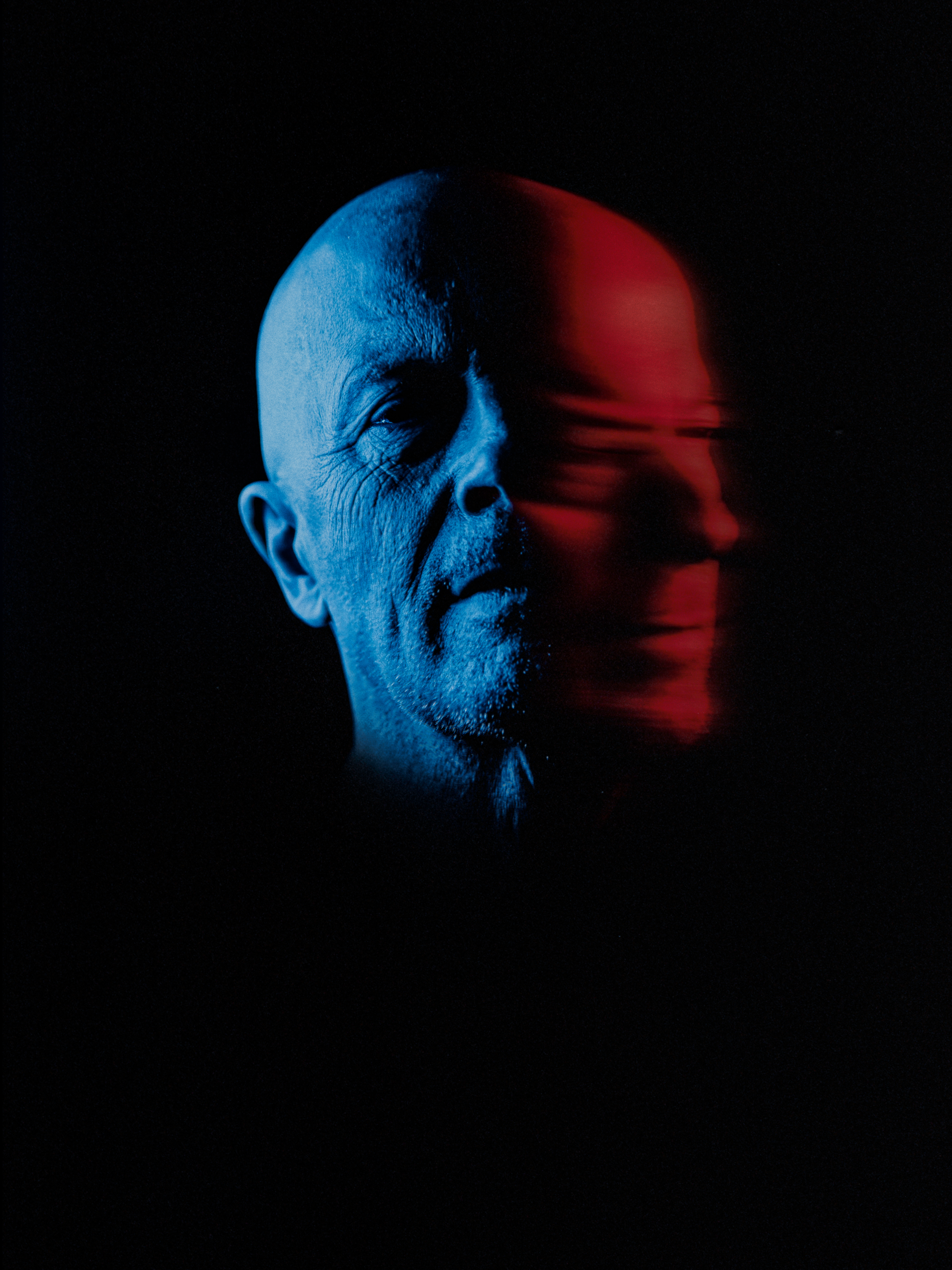

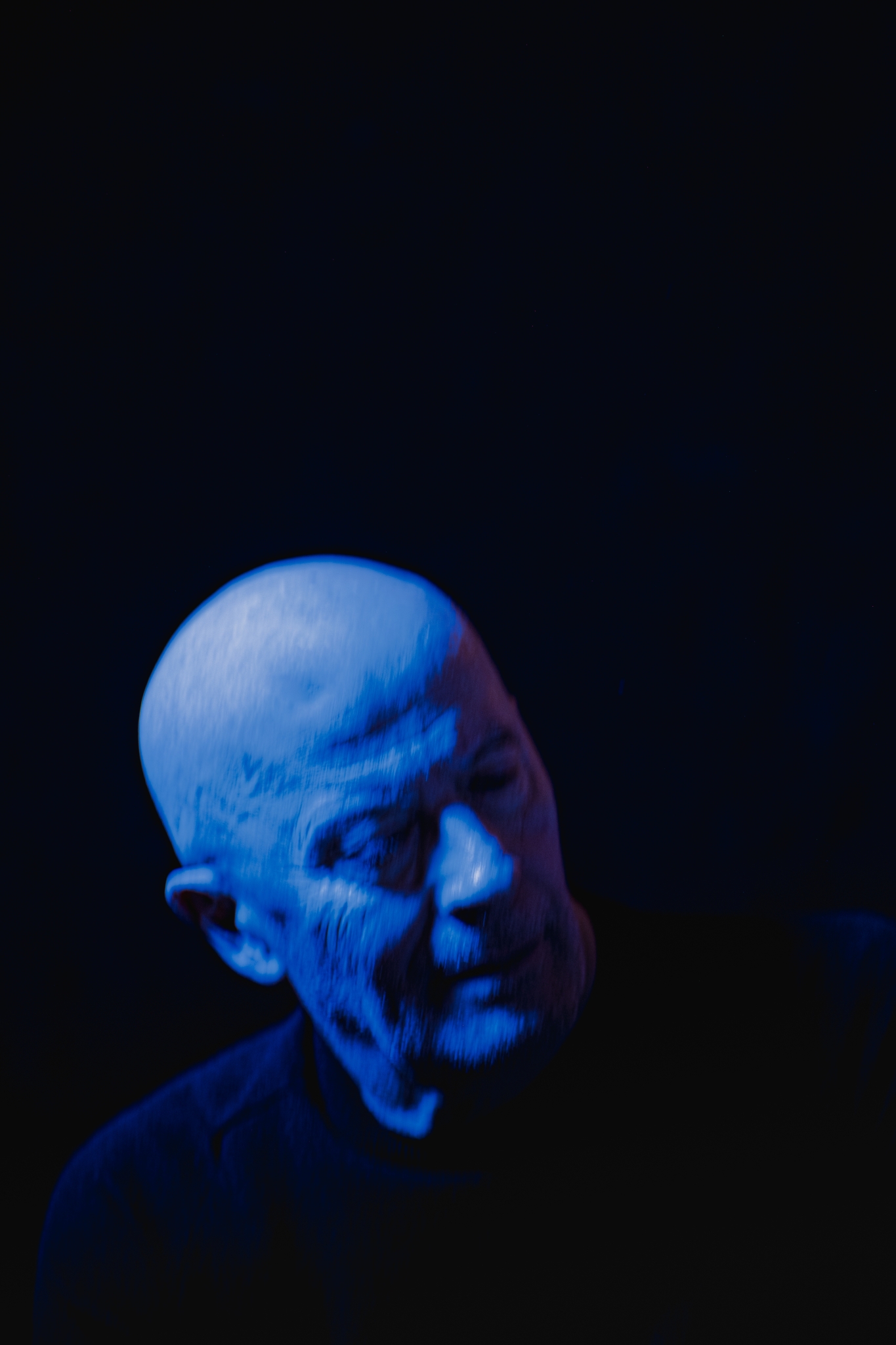

Jacques Audiard

Jacques Audiard. By Laurence Hills.

Unlike Carax or Desplechin, he doesn’t focus on telling stories about French society. And in fact, he consciously acts against this. “I get tired of seeing the same faces in France,” he tells me coolly. “There are many people doing that already.” Instead, his films (particularly in his recent period) are about ethnic underbellies either in France or elsewhere in the world: Tamil refugees in Dheepan (2015); Algerian and Corsican prison inmates in A Prophet; the Russian mafia in The Beat That My Heart Skipped (2005); American gunslingers in The Sisters Brothers (2018), and Mexican cartels in Emilia Pérez. An interest in crime stories has earned him the moniker “French Scorsese”. And he appears to be having a lot of fun ticking away a series of cultural identities to explore and set about trying to understand them, almost as though he is an investigative journalist, I tell him. “That’s because I’m a curious person,” he tells me. During his life, Audiard has travelled extensively with projects, and will continue to do so—there’s no greater pleasure, he admits. “[Jacques] is always travelling, and so it’s hard to catch him,” a Parisian journalist for Le Figaro, who knows Audiard personally, explained to me. But his voyages have deeper meaning.

“Another reason I shoot abroad is that I believe the function of cinema is identification. It brings up a mirror to the societies it is made in. The first big American film was The Birth of a Nation (1915).” For good or bad, he says, it holds up a mirror to the America of that time. “And I believe the power of cinema is not only holding up that mirror but of helping the collective understand and reconcile themselves.”

Like Audiard’s previous films, there is a social message that underpins his narrative: Mexico’s struggles with criminal corruption. As a young man, Audiard travelled to the country and has continued returning over the years as a tourist. “When I was 23, I remember finding the country ‘cute’,” he explains. “And there was all this corruption that felt exotic.” He watched as the corruption grew worse on each return, and started to infiltrate daily lives: “I noticed the impact of the drug cartels; women and journalists being killed and so on. I found that increasingly depressing.” Then he came in contact with Écoute by Boris Razon (2018). In the book, a minor character—a hyper-masculine drug kingpin—undergoes a gender transition to evade the law. The stars were aligning, and his narrative was taking shape. “They haven’t translated Écoute into English, but it’s excellent,” he assures me. One of his heroes is Philip Roth, who also deals with paradoxes around sexuality and identity. “And there is a huge paradox that lives within this character who goes from the most violent type of man and seeks femininity, and that makes you think: what did this character live through to get to this point?” In the film, this is Menitas, played by Gascón, and later the titular character Emilia Pérez. What really interests Audiard is the idea of someone changing their lives: “How many chances do you get to change your life,” he tells me. “And crucially, at what cost? What do you gain? It’s like a screenwriter: you write an epic; the story of the arc of a character. I’m more interested in the concept of people changing lives.”

When Audiard finished the book, it gave him a new reason to visit and develop his ideas. Developing the story as a musical was a more inspired way to approach the brutal world of the cartels. “In a country that is suffering, what better way to portray suffering than by singing and dancing?” he shrugs. “If you’re going to be serious about it, you are suffering twice as much.”

Many of Audiard’s films have featured different languages. “I’ve always been drawn to the musicality of language,” he tells me. For Emilia Pérez, this grew into a desire to work with music itself (in Spanish, which Audiard does not speak, to make it a bit harder). It’s certainly ambitious. Again, just don’t mention the challenges. “It was fine,” he grins. “The work I do with actors is all about picking the right notes anyway.”

Jacques Audiard and Karla Sofía Gascón on the set of Emilia Pérez (2024)

“When you decide to do a musical, you allow your imagination to run wild,” Audiard says, bearing a wide grin. “And I don’t need much to let my imagination flow. Before I would’ve said the idea of making a musical came to me suddenly. But the more I think about it, there were signs along the way and this is a natural progression.”

There was a crucial, and delicate decision, he made to preserve the fantasy tone he was after. While set predominantly in Mexico City, Emilia Pérez was shot on soundstages in Paris: “I shot on a soundstage, not on location… Why? Because the soundstage creates an artifice. It’s as close as possible to the opera.” This might come as a surprise, but apart from Cabaret (1972), Hair (1979), and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), all of which he appreciates for their political angles, musicals have never really been Audiard’s thing. The film was first intended to be an opera libretto. Four acts and set-pieces with characters that were more like archetypes. The opera still exists in the film’s identity; there is a tragic ending and a diva in the spectacle and thundering power of Gascón’s performance, who has more in common with a Maria Callas or Renata Tebaldi than Judy Garland and Julie Andrews (although Saldaña and Gomez are a bit more Broadway). On my second watch I had a very good time approaching it as a staged production. But there is an eclectic mix of sounds, from tango to rap and mariachi music, all of which serve the tone and setting. “An opera doesn’t need to be refined,” Audiard explains. “It’s kitsch; ridiculous. You have to allow it to be like that.” The vibrant “kitschiness” of neighbourhoods like Roma Norte and Juárez are brought to life, I tell him. And he is happy to hear that.

Much of this is due to his long relationship with his set designer and creative lead Emmanuelle Duplay and his costume designer Virginie Montel, who has worked with Audiard for decades, and understands his “perfectionist mentality”, as she tells me in a brief interview, just after I meet Audiard.

The next difficulty was becoming fluent in the language of stage productions, dancers, and singing coaches. But it was another that Audiard welcomed. “We had to open up all these rehearsals,” he says, smiling, relishing the challenge. “I found the process absolutely exhilarating, and then I learned how to interact with certain professionals. Because I’m not in the music industry, I didn’t know how to speak to dancers or singers, so I had to learn how to communicate.”

Audiard could be 20 years younger than his 72 years. He was born in Paris in 1952, a sweet spot to come of age in the 1960s, as the Nouvelle Vague transitioned from art-house rebels to respected mainstream revolutionaries.

His father, Michel Audiard, was a filmmaker known for his humourist films. The young Audiard wanted to be a philosopher, but instead, he followed in Michel’s footsteps. It has been said that Audiard is the torchbearer of the French New Wave; a director who has a grasp on the converging of reality and unreality. I think of Emilia Pérez as his version of Jean-Luc Godard’s A Woman Is a Woman (1961), where he follows his parable on street life Breathless (1960) with a more fantastical vision. He made a modern French New Wave film, too: Paris, 13th District (2022), a black-and-white drama about multi-ethnic Parisian 20-somethings finding love.

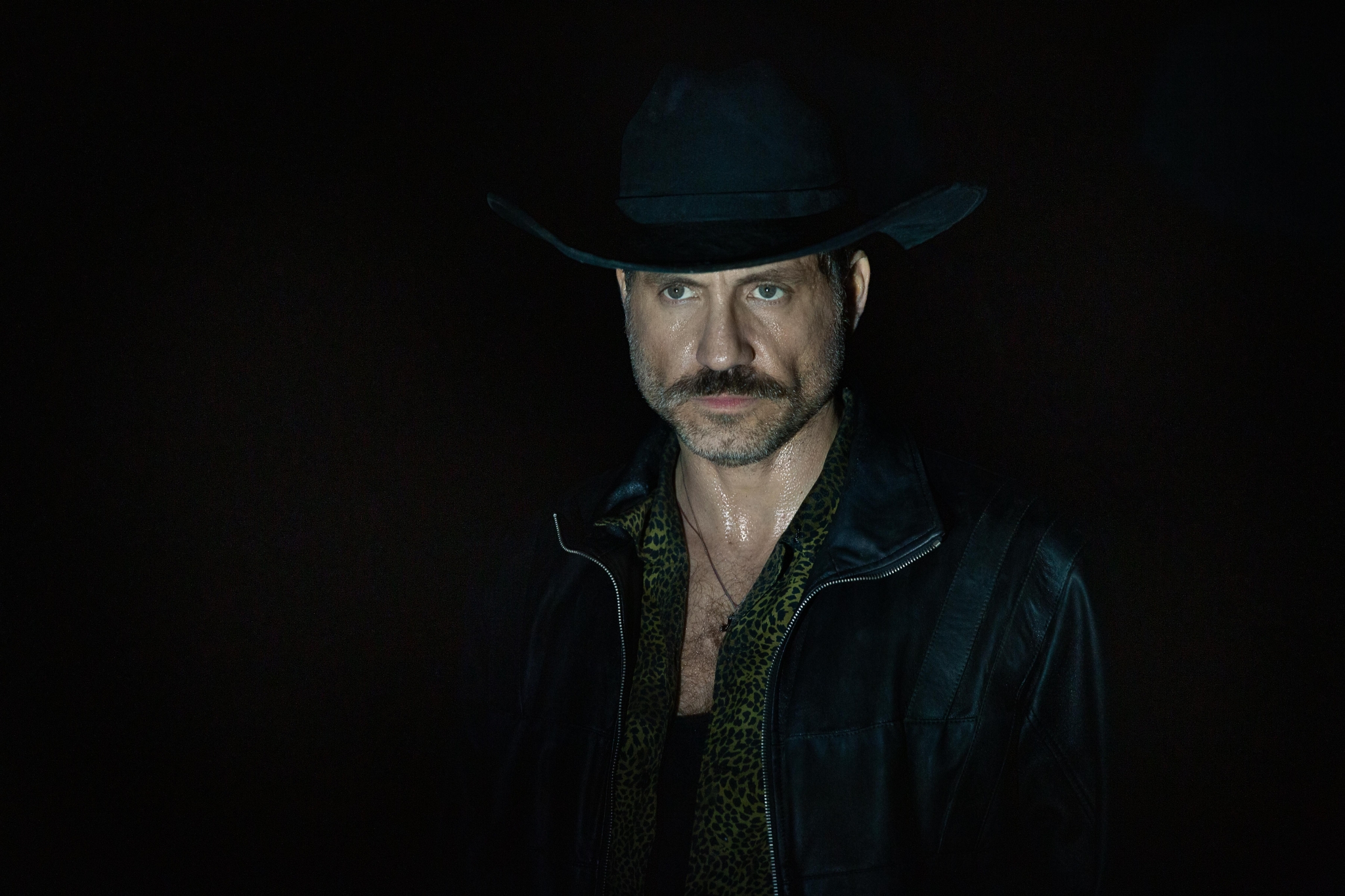

But I think—and this might be a stretch that reaches all the way to the Champs de Mars—that Audiard resembles Godard in that he has an “auteur’s style”. His black sunglasses, nonchalantly thrown-on scarves, and fedora hat (although, recently he’s swapped it for a baseball cap) have given him a recognisable look. In the bustle of the Cannes Film Festival, I could spot Audiard through a squint at events or press activities, and his stylish presence is clear to me now, when I think back to interviewing him. Through his experimental approach, his interest in street life, and his style, he is the closest bridge we have to the essence of the Nouvelle Vague.

He is famous for discovering great talent and giving them a platform to shine. Speaking with Tahar Rahim, he mentioned how he coincidentally shared a taxi with Audiard. “I told him I was a fan,” Rahim says. Afterward, the filmmaker contacted him for A Prophet— the role that propelled Rahim’s career. There are countless stories of Audiard behaving this way; being a guide and a teacher, working from instinct and through difficulty, but doing so without compromise. “It’s because I have faith in cinema.” Not that everyone shares his view. “The worry is that I don’t always like what I’m seeing at the moment. You can’t have faith if you’re the only believer out there.” As he pointed out to me at the start of our conversation, the word challenge does not reside in Audiard’s vocabulary—for good reason: that would be admitting defeat. “You think I’d learn my lesson by now,” he smiles. “But I can’t help it.”

Editor’s note: the above interview took place and was written in 2024.

Foot Note

The Essential Jacques Audiard

See How They Fall (1994)

A Self-Made Hero (1996)

Read My Lips (2001)

The Beat That My Heart Skipped (2005)

A Prophet (2009)

Rust and Bone (2012)

Dheepan (2015)

The Sisters Brothers (2018)

Paris, 13th District (2021)

Emilia Pérez (2024)