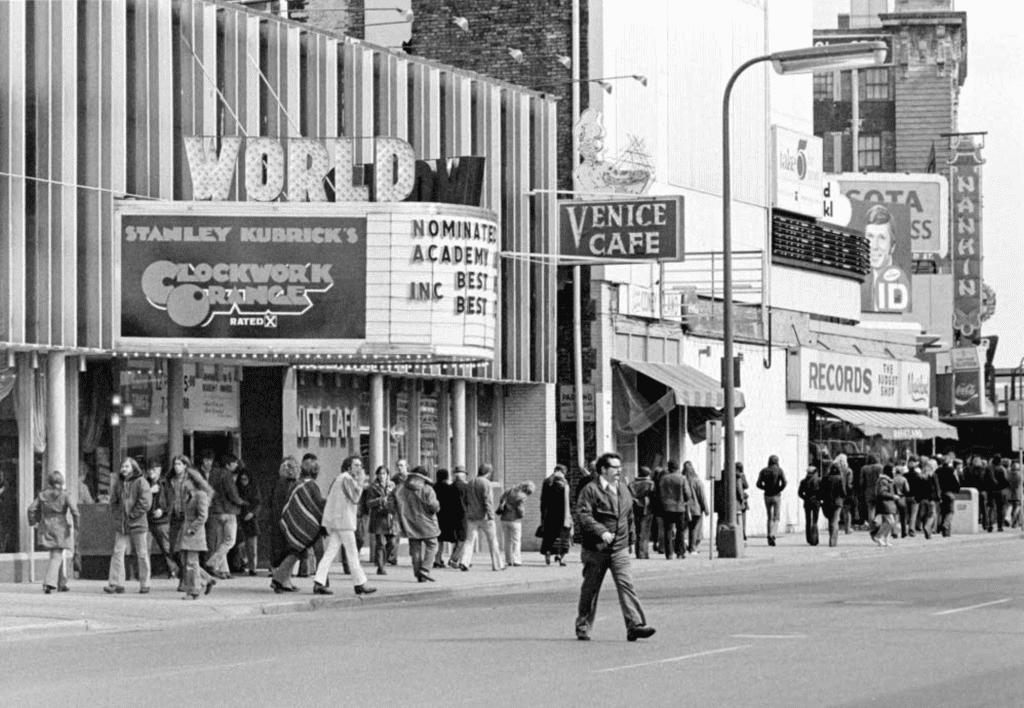

My first exposure to sex in the cinema was when I went with my brother Joel to see John Cassavetes’ Husbands at the Downtown World Theater in Minneapolis. I was twelve years old.

I vividly remember the movie’s first scene—Cassavetes, Peter Falk, and Ben Gazzara lengthily vomiting in adjacent stalls in a public toilet. I also vividly remember the movie’s being in black-and-white, which—a glance at IMDB now tells me—it wasn’t. So, so much for vividly remembering. I’m certain about the vomiting though, and that the three men then proceeded to have loutish, larkish adventures, encountering women who were sexual but not glamorous and speaking dialogue which in a movie theater in Minneapolis in 1970 seemed surreally mundane and which I’d now conjecture was improvised. The theme of the movie, so far as a twelve-year old could discern it, was that it’s very hard to be a man.

I was thunderstruck. I thought, not, “This is a terrible movie,” and not, “This is a wonderful movie,” but, “This is a movie?” Then, at a certain middish point in my ridiculous journey through life, I found myself working with Ben Gazzara. I was excited. I tried to describe to him my experience in that movie theater off of Hennepin Avenue where I sat in the front row at a matinee whose entire audience was my brother and myself and watched Ben and his two colleagues vomiting and escapading and having sex, sex, SEX, an experience in which my artistic horizons were neither lifted nor lowered but somethinged forever. Well, of course, at the time, Little Ethan didn’t know he had artistic horizons, much less changing ones, and didn’t know anything about sex; all he knew—as I tried to explain to Ben—was that the movie confused him; he didn’t understand any of it. And now here was Little Ethan, an adult, talking to Ben Gazzara, and still not quite understanding it, but that was okay, now, however alarming it had been, then.

Ben looked at me like I had just plucked his hat off his head and was now squatting in front of him shitting in it. Clearly, to Ben’s mind, I was not delivering homage. But I didn’t mean to disrespect him. Or his art, or his friends’ art. I was only trying to tell him—well I still don’t know what I was trying to tell him—but maybe it was that, then, knowing nothing about movies except for Hollywood movies and nothing about sex, much less “real” sex, the fraught sex that grown-ups apparently engaged in, I was anxious to learn more about both. I did gather from his movie that it was fraught sex, that sex and suffering were connected; I got that loud and clear. However, I may misremember Husbands, I know it was telling me that.

And then, now, just a few days ago, I saw the movie Joyland, which is about how confusing sex is in Pakistan. Well, why should Pakistan be an exception? My point once again is not that that’s a good movie—Joyland—or a bad one. I happen to think it’s a good movie, until the end maybe, I don’t know about that going-to-the-ocean, but it’s hard to be a good movie your entire running time. No, my point is sex. Or sex in movies. There are Hollywood movies, where sex is simple, and Joyland/Husbands movies, where sex is complicated, and modern mainstream movies, where sex is slick as a yogurt commercial.

And then there’s sex in the movie I just made with my wife, Tricia Cooke, who’s a lesbian—one more thing that Little Ethan in the front row of Husbands in Minneapolis in 1970 did not foresee (can you blame him?) The sex in our movie Drive Away Dykes is sweet and simple, tending to Hollywood I hope, not to yogurt commercial, but that’s not my point. Above and beyond (or below and beneath) movie-sex there’s sex in real life, and maybe my point is that it’s confusing, all of it. And you can choose (but are you really choosing?) which kind of sex to have and which kind of movie to watch and which kind of movie to do and whether to make a complete fool of yourself in front of Ben Gazzara as you put sex and movies and life into one great big blender and hit PUREE. And what’s the relationship of all those things to each other and to an audience and to you in the front row with your little overwhelmed heart? I don’t know, I’m not a deep thinker, but when I recall it now in the kind of remembering where you get to correct things I stop all attempt to explain and just clap Ben on the shoulder and say, “Never mind, buddy. I was right there with you.”