Coralie Fargeat sits down with A Rabbit’s Foot to discuss The Substance, a body horror exploring ageing, celebrity and corporeal destruction.

The pursuit of eternal beauty and youth—and its pitfalls—is well-trodden territory in cinema. Death Becomes Her (1992) is Robert Zemeckis’s high camp tale of two actresses who drink a potion to stay forever young, becoming accidentally immortal. Pedro Almodovar’s The Skin I Live In (2011) follows a plastic surgeon obsessed with creating a flawless epidermis for his imprisoned patient. Helter Skelter (2012) is Mika Ninagawa’s horror about a supermodel’s attempts to stay popular through full-body cosmetic surgery. In a sense, all of cinema, wittingly or not, pursues eternal beauty, as a spectre machine with the capacity to play and replay footage of actors in their youth—whether that be Marilyn Monroe or Marlon Brando—long after they are rotting in the ground.

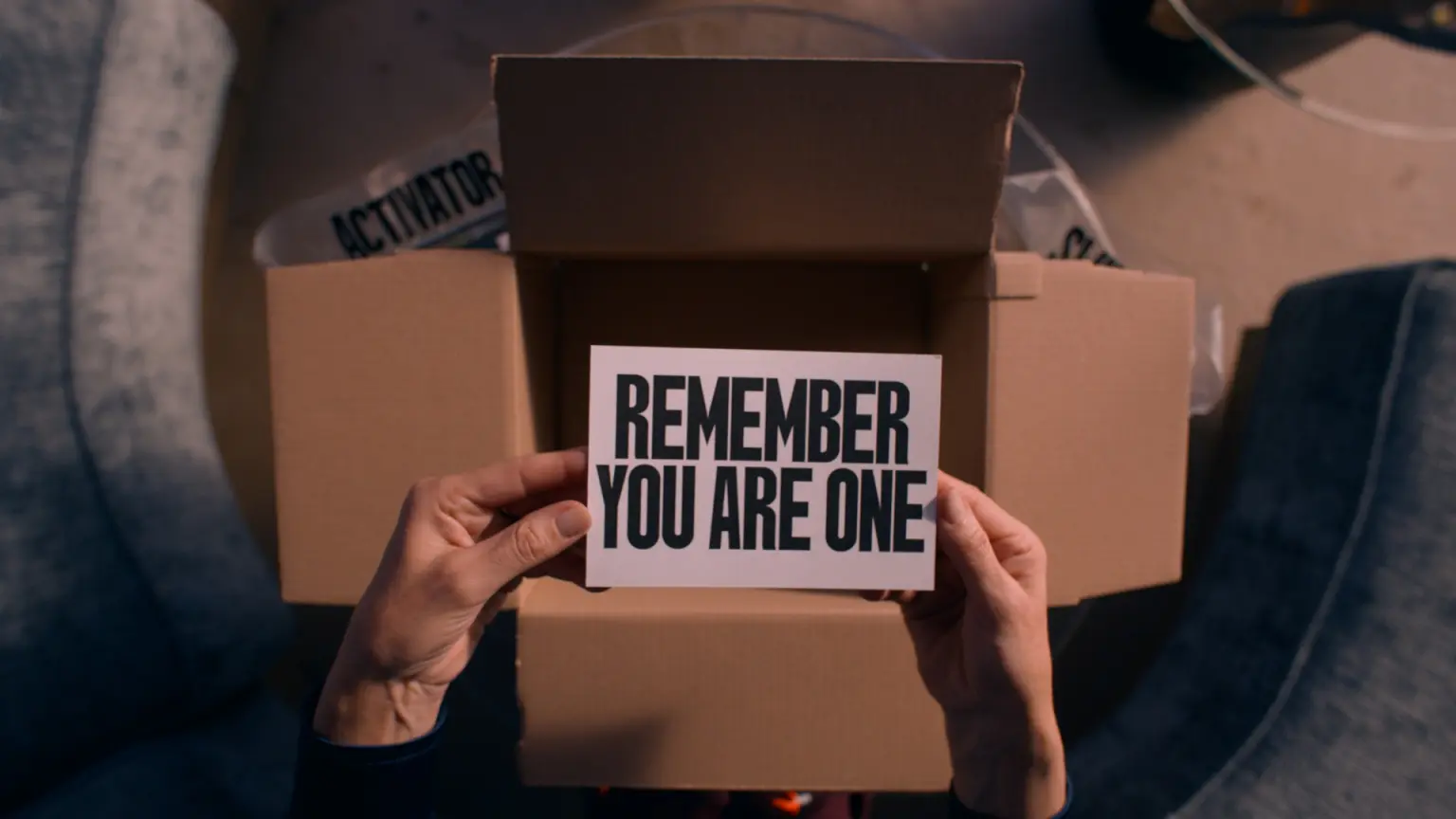

Still, nothing can prepare you for The Substance, Coralie Fargeat’s 2024 body horror about ageing, beauty and celebrity. In it, Demi Moore is thinly veiled as Elisabeth Sparkle, a famous actress past her prime, who presents 80s-inspired exercise videos and lives alone in a plush apartment with an unbroken view of Hollywood. Sacked by her boss Harvey, over a lunch in which he sucks the brains out of prawns, she quickly spirals into a crisis. A solution is presented to her by way of the Substance, a lurid green, generically branded injectable which allows Elisabeth to create Sue (Margaret Qualley), a younger version of herself who picks up Elisabeth’s career where it was dwindling off. “Remember you are one,” is the product’s tagline. The two women—forced to “switch” every seven days—end up at war with each other, and The Substance descends into a carnage which by the end feels as if it is splattering out into the theatre seats.

A Rabbit’s Foot caught up with the director from her apartment in Paris to talk genre cinema, motherhood and making deals with the devil.

KG: What ties your debut feature Revenge with The Substance?

The Substance is really a continuation of the work I started with Revenge. I knew I wanted to continue writing my own films and keep creating my own worlds and I also wanted this movie to be a genre film. Genre is a wide appellation that kind of embodies everything that is not realism. It can be sci-fi, it can be horror, it can be action. Everything that’s not in everyday life and allows you to cross boundaries and go very far and extreme.

I wanted to address the themes that I had started to develop in Revenge about feminism, about what it is to be a woman, how you’re seen, the powerful imprint you have in public space, which eyes are on you, how you’re seen, how you’re valued, which I have been influenced by since I was very young. I turned 40 and was more impacted than ever about what it’s like to be a woman, the feeling that if I wasn’t young and pretty and sexy, I would be totally erased from the surface of the earth. So there was this kind of emergency, this vitality to the things I speak about in my film. But I address it in this form I love, which is through pure entertaining genre.

KG: When I watched the film the second time, I couldn’t help but see it as a film about motherhood. Was that something you were interested in exploring with the movie?

CF: Not in a conscious way, but it’s an important theme in that it defines the place that we have in society—if we are a mother, if we are not a mother, if women are able to have children or not. There was one moment that was removed from the editing. When Elisabeth is at lunch with Harvey and he’s eating his shrimp and says, “but anyway, don’t worry, now you’ll have time with your family” and she says “I don’t have kids,” and he’s stuck.

I’m exploring the place we give to women who decide not to have children, who achieve differently, or give birth to something in a different way. I think I give birth through my art, through what I create. What you leave after yourself is definitely a very big theme of the movie. Because it’s also about the fear of ending, that we are going to be replaced and we are mortal. It’s a fear of the human condition. I think having children is a way to perpetuate yourself in the world. I had a very strong reaction to David Cronenberg’s film Dead Ringers (1988). The heroine can’t have children, and she says that when she’s gone, everything is gone. In The Substance, I’m trying to represent a desire to exist in the world in another form from being a mother. I call it the ‘birth scene’ when Sue is created. But the fact it comes from a different process than a natural birth is important to me.

DEMI MOORE IN THE SUBSTANCE. IMAGE COURTESY MUBI.

KG: Absolutely. Even in the opening scene where we see the Hollywood star, there’s this idea of legacy or afterlife, which really contrasts to the rest of the film which is about this messy reality of being a human being and being finite.

Another link with Revenge, I found, was how your protagonist’s bodies are being destoyed and mutilated, but they also have this residual life force and resistance and drive to survive. That for me is what gives your films their feminist tonality.

CF: Yes, it’s a lot about our sensations and, you know, getting into the flesh and bone of how our body. As human beings in general, but especially as women, our body is such an object of discourse, of contemplation, of judgement, of transformation, that it plays a major role in our lives whether we hate it, whether we take care of it, or whether we want to destroy it. I’m interested in exploring in a visceral way, how our bodies can be destroyed, but also how they can fight and survive that destruction. It’s about more than ageing. Her deforming, it’s as if all her angry thoughts are being represented in this huge deformed knee, or this extra hunched back. It was a strong way for me to imprint her inner soul on the body. I would say the final liberation for her character is when she doesn’t have a human body anymore. When she’s reunited with her Walk of Fame star, she doesn’t have to care anymore about what she looks like. There’s this kind of moment of relief.

THE SUBSTANCE. IMAGE COURTESY MUBI.

KG: Having Demi Moore in the lead role, playing an ageing actor… was it important that the casting was self-referential?

CF: Yeah. I work with symbolism. There isn’t much dialogue in my films. So you can use symbolism to develop strong ideas. That’s why I chose my main character to be an actress, because who can better represent, in a heightened way, the concerns about ageing and looks? She concentrates those concerns 1000%. But she’s a symbol of what we as normal women live through as well. It’s also this collective unconscious Hollywood idea. So getting an actress who is herself an icon who is known and scrutinised for her beauty and appearance, meant this wouldn’t need any explanation.

The challenge was to work with an actress who had that status. Because I knew I’d be confronting her with her worst phobia. We were thinking about different names and Demi came to mind. I thought we shouldn’t waste time even sending her the script. When I heard she responded positively, I was surprised. I discovered a different side of her. I realised she was in a phase of her life where she had confronted these issues in a painful way but had gotten a lot of strength for herself regarding them which is why she felt playing the role wouldn’t put her in danger. She was strong enough to show vulnerability.

MARGARET QUALLEY IN THE SUBSTANCE. IMAGE COURTESY MUBI.

KG: You have two lead roles in the film, and I found it interesting that they are not really in any scenes together, even though their characters are so linked. Was that an interesting tension to work around as a director?

CF: My instinct when we started was that I didn’t want Demi and Margaret to share too much ahead of the shoot because although the movie is about replicating yourself, it’s really about the idea that if you have a different body, even if you’re the same person, you’re going to think completely differently. You’re going to live things completely differently. Even if the day before you were in that other body, if you wake up in another body, your world experience is not the same. That’s the idea, that the different voices we have within ourselves can be very powerful and antagonistic, even if we are one, even if we’re ‘us’. We had a few readings and some rehearsals for the fights, but basically each of them could create their own character. I didn’t want them to have the same gestures or any continuity like that. There was a chemistry we needed to find, but at the same time I wanted to preserve the experience they had for themselves in the movie.

KG: The Substance‘s title refers to a product that Elisabeth buys, this thing that promises to make her young again, and it has this very distinctive branding and identity. What were the inspirations that inspired its aesthetic?

CF: I knew I wanted the product to be this mysterious thing that exists but at the same time doesn’t exist and is dehumanised and is basically a voice on the phone. You never get to see anyone when you receive it. It’s like when you call administration and you just have those ‘press one, press two’ options. I liked the fact it was something a bit under the table, a bit black market. When I write I let myself go with ideas that arrive. I don’t analyse them or intellectualise them at the time. And the deeper meaning often comes to me after. The fact that she becomes a number, she doesn’t have a name anymore. She calls and says Elisabeth Sparkle but she has to say 503 otherwise no one answers. It’s basically this pact with the devil. This appealing thing that is promised, but it isn’t handled by real human beings. You know something is there but it comes to you in this mysterious way. I think it has a lot of meaning in itself, and then, also on an unconscious level. The voice on the phone is really the voice you use to talk to yourself: Do you want to stop? That voice that teases you and makes your addiction stronger.