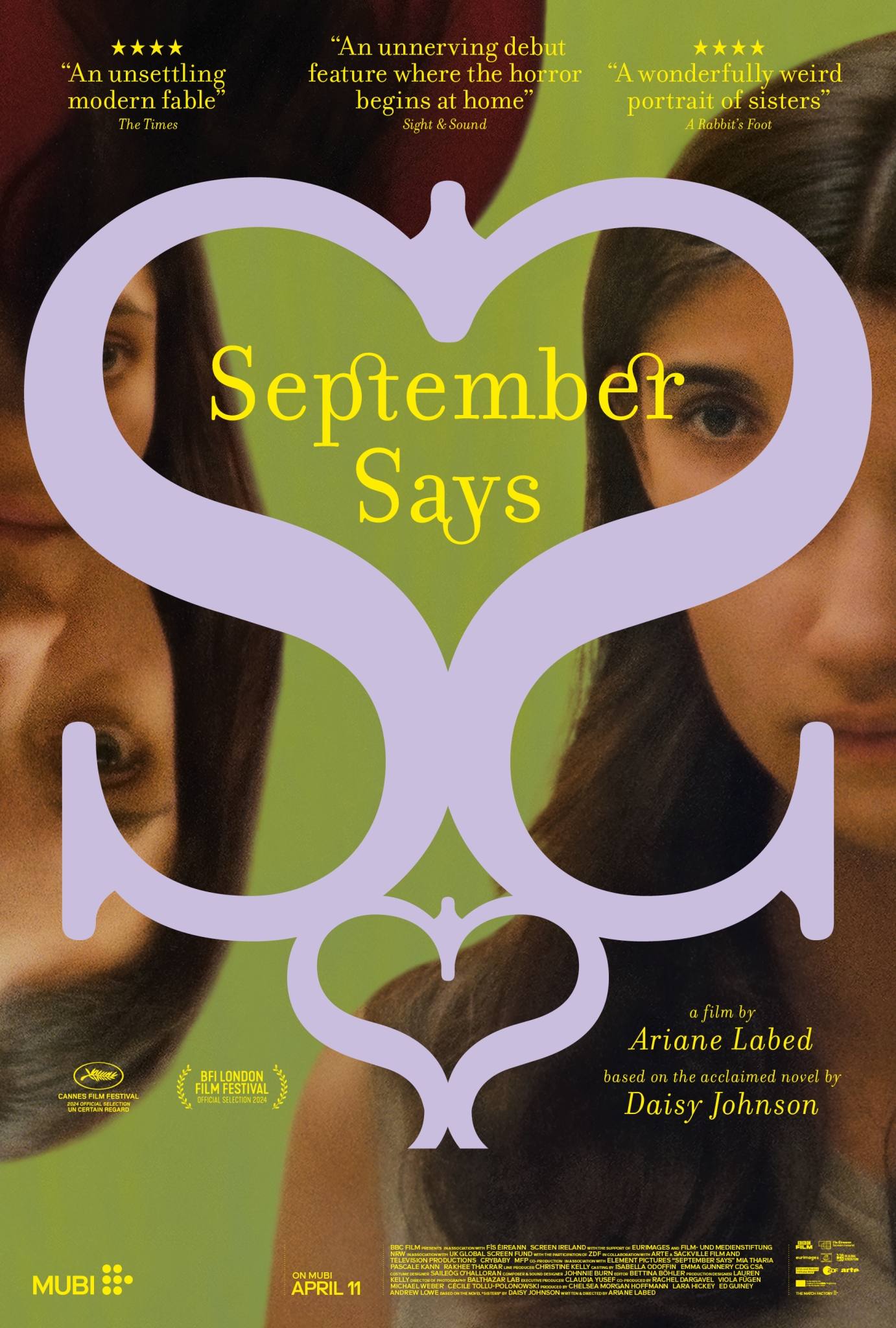

An actor and director, Ariane Labed is an enigmatic figure in contemporary cinema, and has herself always felt like an outsider. Kitty Grady met the September Says director in Athens to talk about her breakout role Attenberg, working with Brady Corbet and why she doesn’t trust language.

Who is Ariane Labed? It’s a question I have come to Athens to answer. From London, I fly south, coasting in the twilight over vast plateaus of rock which are empty apart from the occasional house as a torch. I land two hours into the future. London to Greece ‘jet lag’, my friend later tells me, is a real phenomenon. I spend my first evening playing catch-up in a city that is falling asleep while I am still wide awake.

A director and actor, Labed has a habit of creeping up in work I like—Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir and Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist (she appears in the 1980s epilogue, delivering a speech about her uncle László Toth in Venice). I watched her directorial short film debut Olla—about a Russian mail order bride —with great amusement. I want to know who this woman is: at once French and Greek, famous but not quite, and seemingly beloved by many of our great contemporary directors. I first saw her in person at a press junket for her debut feature film September Says at the Cannes Film Festival last year. In a corporate room of the cruise-like Palais she held court as a scene of international journalists asked questions, disappearing occasionally behind a dramatic puff of her vape.

Labed comes up behind me when I meet her next. We are at Foyer Espresso Bar in Pangrati, a middle-class area of Athens which has the horse-shoe shaped Panathinaiko Stadium—home of the first international Olympic Games—as its key landmark. Labed, who lives a short walk away in the neighbourhood of Vyronas, has just returned from the island of Tinos, and after some back and forth about where and when to meet, she is here, sitting opposite me, on, what many Athenians tell me, is the first properly warm day of the year.

As we order coffee—iced latte for me, espresso freddo for her, asked for in her impeccable, but French-accented Greek—I ask Labed about the theme of language in her work, why she creates and portrays characters who struggle with language or fail to understand one another. In Olla, the Russian bride is unable to verbally communicate with her French husband (he even changes her name to Lola in his efforts to assimilate her). Labed explains that feeling like an outsider is a deeply personal quandary. “I live in a country that is not my first language. I lived in the UK for ten years and I never learned to speak proper English. I think that language is part of being a foreigner, and since I’ve been a foreigner all my life, it’s part of my identity.”

Labed was born in Athens in 1984 to French parents. Her surname is Algerian in origin—her great grandfather having moved to France after WW1. “They used Algerians like pieces of meat,” she notes sternly. Her parents were school teachers at the French school in Athens, and they were part of an insular expat community amongst other French people. They stayed until she was six, before relocating to Germany for another six years. “It was the same thing,” she says. Then it was time to go to France. It was a disillusioning experience. “They told me, that’s home. I didn’t connect with it. I’m supposed to be in my country and I don’t really feel I belong,” she recalls. Even in her native language, she failed to feel understood. “The difficulty of communication is one of the things that really interests me. Most of the time when people try to use language to express themselves, it fails. The only moment I feel like people can connect is through physicality, or animality, or things like that. Words, I don’t trust them that much.”

After moving to Provence for her acting studies, Labed came back to Athens at the age of 24 for a theatre role. It was supposed to be a nine-month stint but she met Athina Rachel Tsingari, who cast her as the lead in her second feature Attenberg. The film centres on Marina, a sexually inexperienced woman in her early 20s with a sick father. The title refers to the David Attenborough documentaries she compulsively watches. She took on the part, despite not really knowing the language. “It was a problem that I was French,” she recalls, explaining how a language coach helped her with Greek. “I translated it so I knew what I was saying, but they weren’t words I was familiar with.” Labed’s lack of fluency adds a naivety of her character, whilst making way for more honest expressions of the body. In the opening scene Marina and a friend stick their tongues down each other’s mouth. In a regular interlude we see them dancing, somewhat insanely, down a pathway in uniform. As a party trick, Marina dislocates her shoulders (Labed confirms this is actually her doing this).

“Most of the time when people try to use language to express themselves, it fails. The only moment I feel like people can connect is through physicality, or animality, or things like that. Words, I don’t trust them that much.”

Ariane Labed

The film is categorised as part of the so-called ‘Greek Weird Wave’—a brand of off-kilter, transgressive cinema that depicts contemporary Greece away from its recognizable clichés. “I hate that term,” says Labed, to my surprise. “I don’t think it exists. It’s like three films, two directors. And it’s not a wave. I just don’t get it.” The other titles—Dogtooth and Alps, are directed by Yorgos Lanthimos, who also stars as Labed’s love interest in Attenberg—their mechanical foreplay is excruciatingly unerotic, and I feel strange having watched it alone in my hotel room the night before. It is a role that has somewhat haunted Labed, who a relative unknown—won the Coppa Volpi Award at Venice Film Festival for her performance. “I’m still searching for something as good as an actor,” she tells me. “I have done other films that I am very proud of, but I have done some that I am very ashamed of. I think as any creative profession you have the stuff you just do when you need to eat something. But when you start with such an amazing artist, with such beautiful, interesting language, it’s hard to continue because you keep hoping and searching for something that unique and inspired.”

After Greece, Labed moved with Lanthimos, to whom she is married, to London for nine years—another place she felt like an outsider. “I never felt completely that I belonged…I was always trying to understand what people mean, because they don’t tell you it’s bad or I don’t like it, and that makes everything so difficult for me to understand,” she says, of the (painfully familiar) trait whereby British people are unable to say what they really mean. “I was trying to translate and be like, I think that means they don’t like it. You have to read between the lines.” Brexit—the 2016 referendum that resulted in the decision to leave Europe—she adds, felt like a less ambivalent “fuck off’”. “I feel European,” says Labed. “Whatever that means.”

It was while in London that Labed was approached by BBC Film and Element Pictures to write and direct an adaptation of Sisters (2020), a gothic novel by Daisy Johnson about September and July, two imaginative young sisters who, violently close, move from Oxford to a remote house in Yorkshire with their mother, Shula, who is mentally unstable. Labed immediately felt connected to the story—narrated mainly by July—from the first read. “I never asked Daisy Johnson if she’d seen Attenberg, but I could see some links between this young woman who creates another world in order to manage it. People that are considered outsiders building another language.” Filmed across the UK and Ireland, Labed’s September Says (in French the title is September July to avoid misunderstanding it as September “seize” or 16), creates a vision of the British Isles which, through her foreign lens, is defamiliarizing, without any grounding sense of heritage or nostalgia. Clips from David Attenborough also make their way in, alongside a British reality TV about dating which is similarly animalistic.

It is a film about the growing pains of adolescence, and the unhealthily close friendships girls are particularly prone to. (There is a big twist, which I won’t reveal, but Labed jokes that they “should do the second ticket half price.”) The director, who has two older sisters, drew closely on her own experiences as a teenager. “I had a group of friends that were kind of fucked up,” she says, recalling once again the “alienated” period of her life after she returned to France at the age of 12. “I wanted to talk about that period of time without all the clichés. I really consider the teenage years the most important time of our lives. Slamming doors, scrolling phones…I think it’s way deeper than that. It’s a period of time that is truly between life and death.”

It is also a film about the messy ways women behave outside of the male gaze. In one scene, Shula has sex with a stranger she met at the pub, we see her bemused face and hear her mundane thoughts in voiceover as he does his business. This scene seems to find its flipside in Olla, when the protagonist masturbates at the kitchen table whilst eating a packet of cheese. “We don’t have fun, maybe as men imagine,” says Labed. “I don’t know how they imagine when we are alone or whatever. It’s dirtier. We’re not lying down and lighting candles.”

We talk for a while about the work of Chantal Akerman, who we agree is particularly good at showing how women roll around at home alone. “She was a genius. She created language… She’s my goddess,” says Labed. Labed cites other directors as influences: Alice Rohrwacher and Kelly Reichardt, Robert Bresson and John Cassevetes, and mentions the photographers Justine Kirland and Joanna Piotrowska, who capture the awkwardness of teenage girls and contorted choreographies respectively, as the key visual influence for September Says. “I didn’t want to have any [cinematic] references, because I think it brings too much weight.”

Her relationship with Lanthimos was naturally formative. “When I met him, I was just starting to get interested in cinema… so he was my film school. All the films I watched, I watched them with him.” They look over each other’s scripts, but for September Says, she first shared it with her mother and sisters. “I love, maybe even more, to talk about films with my mum or my sisters who don’t have anything to do with it,” she explains.

Labed speaks with particular fondness of her work with Joanna Hogg (“the most interesting British director alive”) on both installments of The Souvenir. “I explained that I wanted to understand the way she works,” says Labed. Hogg gave Labed the novel that she famously wrote in lieu of a script. “I was not allowed to tell the other actors,” she notes. “I try to work with people I admire—people that I consider are taking risks and trying something that really matters to me. Even if it’s a small part or a big part, I’m just happy to be involved. And also, that’s my film school. For me, being on set, that’s how I learned to direct.” I ask her about her role in Brady Corbet’s seismic title The Brutalist. “I’m not in The Brutalist,” she jokes of her (admittedly pretty small) part, before expressing admiration of his work. “I love the fact he’s a proper American guy who really wants to work hardcore like a European,” she notes. “Although, when we see that as Europeans, we’re like, fuck you—we dream of making cinema that Americans have. And you’re almost pretending that it’s romantic to not have the fucking money to do it.”

The photographer joins us and we head towards the restaurant called Karavitis, a taverna a few streets away from the coffee shop. “I had forgotten this place existed,” says Ariane, who points out that the road outside, Arrianou, is where she first lived when she moved back to Athens from France. The coincidence of their names felt like a sign, and she explains Ariadne importance in Greek mythology. Ariadne was given a ball of thread by Theseus to help him navigate himself out of the labyrinth after he had slayed the minotaur. The road, in short, was a route back to herself, to a place that would start to feel like home again.

As we sit in the restaurant, filled with families and the odd lost-looking tourist, Labed tells me about her future plans. An acting project this Spring has been pushed, so she is going to use the time to start writing on Tinos. As we chat, she mentions how David Lynch ate a Greek salad everyday. “But never in his lifetime did he come to Greece,” adds our photographer. “It’s a shame as I think he would have liked it, especially the northern parts, where it becomes more mountainous and strange,” continues Labed, her fork stabbed vertically into the flesh of some cucumber. When I Google it later, a Reddit thread tells me that the great director didn’t, in fact, eat a Greek Salad everyday, but a Lynchian perversion of one: canned Tuna, olive oil, feta cheese and tomatoes. The cucumber was missing, swapped for fish. But as far as I can tell, he indeed never made it to Greece.

Kitty Grady was a guest of Mona Athens (mona-athens.com). September Says is available to watch on MUBI.