Martin Brest’s 1992 film has become a crowd-pleasing classic since it first swept cinemas 32 years ago. We talk to the director about the making of his award-winning drama, alongside a special note from star Al Pacino.

It’s the tail-end of 1990. Rows of cork boards line the walls of an old bungalow suite tucked away somewhere on the Universal studio lot, Los Angeles, where director Martin Brest and screenwriter Bo Goldman are dreaming up their Oscar-winning box office hit Scent of a Woman (1992). Or rather, they’re meant to be. The truth is, for the past two weeks, from 9:30AM to dusk, the two collaborators have simply been…talking. And Brest is starting to get nervous.

“We didn’t talk about the story once,” he tells me, Zooming in from his NYC apartment. “We just talked about our upbringing, our lives. Then, finally I just said ’I love hanging out with you, but shall we start working on the story?’” In response, Goldman, who had already begun earning a name for himself as a “screenwriter’s screenwriter”, told Brest something that Mike Nichols had taught him years earlier: that, in script-building, the digressions are the story. “I didn’t really understand what that meant,” Brest admits. “But I came to understand.” What followed was nine more months and 60 hours a week of what Brest describes as “mutual psychotherapy”, during which the pair would eat, sleep, talk, and, piece by piece, assemble the shape of a narrative out of memories of their own lives.

The narrative in question follows Charlie Simms (Chris O’Donnell), a scholarship student at wealthy prep school Baird, who takes a job watching over blind Vietnam war veteran Lieutenant Colonel Frank Slade (Al Pacino) over Thanksgiving weekend, so he can afford to fly home to Oregon for Christmas. Slade is a brash and impulsive alcoholic, but over the course of the weekend, in which he strong-arms Simms into taking him to New York City, a bond forms between them. Meanwhile, Simms is wrestling with a moral dilemma after witnessing three classmates prank Baird’s headteacher, who gives him a choice: expose the culprits, or risk his future scholarship at Harvard.

Chris O’Donnell, Al Pacino and Martin Brest at the 1993 Oscars for Scent of a Woman.

Even if you haven’t seen Scent of a Woman for a few years (like Brest, who, though he considered a rewatch before our interview, opted instead to “just close my eyes and play it in my head”), there are a series of four or five scenes that might spring to mind at the mention of it. There’s the Ferrari scene, in which Slade and Simms fly through NYC in a 1989 Mondial T Cabriolet (with Simms riding shotgun), or the tango sequence, which sees Slade and Donna (played by British-American beauty Gabrielle Anwar) dance to Por una cabeza. Or, if you thought your family get-togethers were bad, look no further than the movie’s centrepiece, in which Slade visits his estranged brother’s family for a nightmarishly stormy Thanksgiving dinner—a scene born from Goldman’s tempestuous relationship with his own brother, and another product of his and Brest’s therapy sessions. “He had this revelation about their relationship. And he said, ’The truth is… he’s no fuckin’ good, and he never has been’. I said ’Bo… I hate to taint this precious moment of self-reflection, but that’s a fucking spectacular line, and I know exactly where to put it.” The line, a variant of which is delivered by Pacino in the movie, is one of its most crucial, telling you everything you need to know about Slade, a man whose spirit is being clung to by a demon.

Multitudes can and have been said about Pacino’s performance as Slade, which earned him his first Best Actor Oscar in 1993. Boisterous and sometimes over-the-top, though utterly entertaining, it’s a far cry from his nuanced turn as Vito Corleone in The Godfather series, which introduced him to the world stage over half a century ago. In some ways, Scent of a Woman marked a turning point for the actor, who seems to have taken elements of Colonel Slade with him to films such as Donnie Brasco (1997), Heat (1995), The Irishman (2019), and more during his later career. Though this act of Pacino’s career, and this performance, birthed an endless stream of parody (some loving and some critical), Slade is a complex character, and with the role comes the terribly difficult task of encouraging a paradox of emotion from an audience. It’s hard to imagine many other actors handling the role with the efficiency of Pacino, who takes the character to the kind of emotional peaks that only he and a few others of his generation could. A version of the character first appeared in Italian director Dino Risi’s original Scent of a Woman (Profumo di donna) in 1974, played by the great Italian actor Vittorio Gassman. “There was something about the nature of the lead character that burnt itself in my skull,” Brest says. “The idea of a raging, bitter asshole, utterly profane, and, even at the time, politically incorrect, who, as repulsed as you are, you can’t help but reach out to and root for.”

Pacino embraced the role, spending time with an armed forces consultant whose job was to teach him how to assemble and disassemble a gun in under 45 seconds with his eyes closed. Every time he did so successfully, the consultant would shout “Hoo-ah”, a phrase that Pacino famously adopted for Slade—according to Brest, the only time Pacino deviated from script was to insert a “Hoo-ah” into a given scene.

Pacino got so into the role that Brest unconsciously began calling him by his character’s name, with the actor responding in kind. In fact, he’s so convincing as a blind man that his eyes, though absent of prosthetics or contacts, seem to take on a glassy quality, at once completely still and full of emotion. He laughs when I ask him if there’s truth to reports that Pacino purposefully blurred his vision in order to get into character. “Surgically? No, but whatever he was doing on the set, it prevented him from seeing. He willed himself not to see in some extraordinary way. I don’t know what the process was…” He thinks for a moment, before surrendering himself to the unexplainable. “He’s Al Pacino.”

A still from Scent of a Woman (dir. Martin Brest, 1992)

There’s a certain old-school, rockstar quality about the way Brest operated in Hollywood during his prime. Despite his filmography boasting big studio franchise hitters, critical darlings, and pop-culture classics like Beverly Hills Cop (1984) and Midnight Run (1988), Brest was the farthest thing from a company man—he was an artist through and through. “I never thought from a career standpoint. That’s just the way I always operated. My philosophy was an extension of film school, where everything you made was a product of your desire. I lived by that model. I waited for an idea to enthral me and then I made it exactly how I wanted to make it. Until my last debacle, I enjoyed total creative freedom for years.”

The “debacle” Brest is referring to with the ominousness of someone afraid they might accidentally summon a hell-demon is Gigli (2003), the only film in his oeuvre plagued by studio interference. Not coincidentally, the rom-com starring Jennifer Lopez and Ben Affleck also happens to be one of the most expensive box office bombs of all time—Brest’s only flop. Unfortunately, in Hollywood, a single failure is enough to nullify an entire career of success, and Brest was consequently exiled from the City of Stars, with Gigli remaining his most recent film to date.

But for the most part, his collaborations with the studio system were largely without compromise, a scenario most filmmakers only dream of. Then again, most filmmakers never make a Beverly Hills Cop, a pop phenomenon so massive that not only did it serve as the three-peat to Eddie Murphy’s star making run, alongside 48 Hrs (1982) and Trading Places (1983), but the wave of it is also still being felt today, with Netflix’s legacy sequel Axel F hitting the streamer this year. “I was not approached for it,” he says. “Even if my career was what it was back then, I wouldn’t want to touch that.”

Considering his track record of only making movies that appeal to his personal artistic sensibilities, Brest’s style of filmmaking is so vast and varied that finding a through-line of authorship within his filmography might prove challenging at first. Even the most casual filmgoer could probably pick a Quentin Tarantino film out of a lineup, but with Brest the tells are a little less obvious, a quality the pop-auteur takes pride in. “I’ve seen people review my movies online,” he says. “They love all the details. They love everything about ’em. Then they’ll concede that it was mediocrely directed. And I laugh, because what they’re perceiving is all I’m doing. I’m not doing fancy stuff, I’m doing inconspicuous stuff. I’m an architect of the emotions of the viewer in ways they can’t see, but they can only feel.”

I ask him if the validation that came with the film’s awards attention, particularly at the Oscars, meant as much to him as it did to Pacino, who had long been denied a little gold man. “I lost faith in the Oscars in 1980 when Raging Bull didn’t win,” he replies. “I realised that this wasn’t God coming down and saying this is the best movie. What was the best breath you took while you’ve been talking to me? Who the fuck knows?”

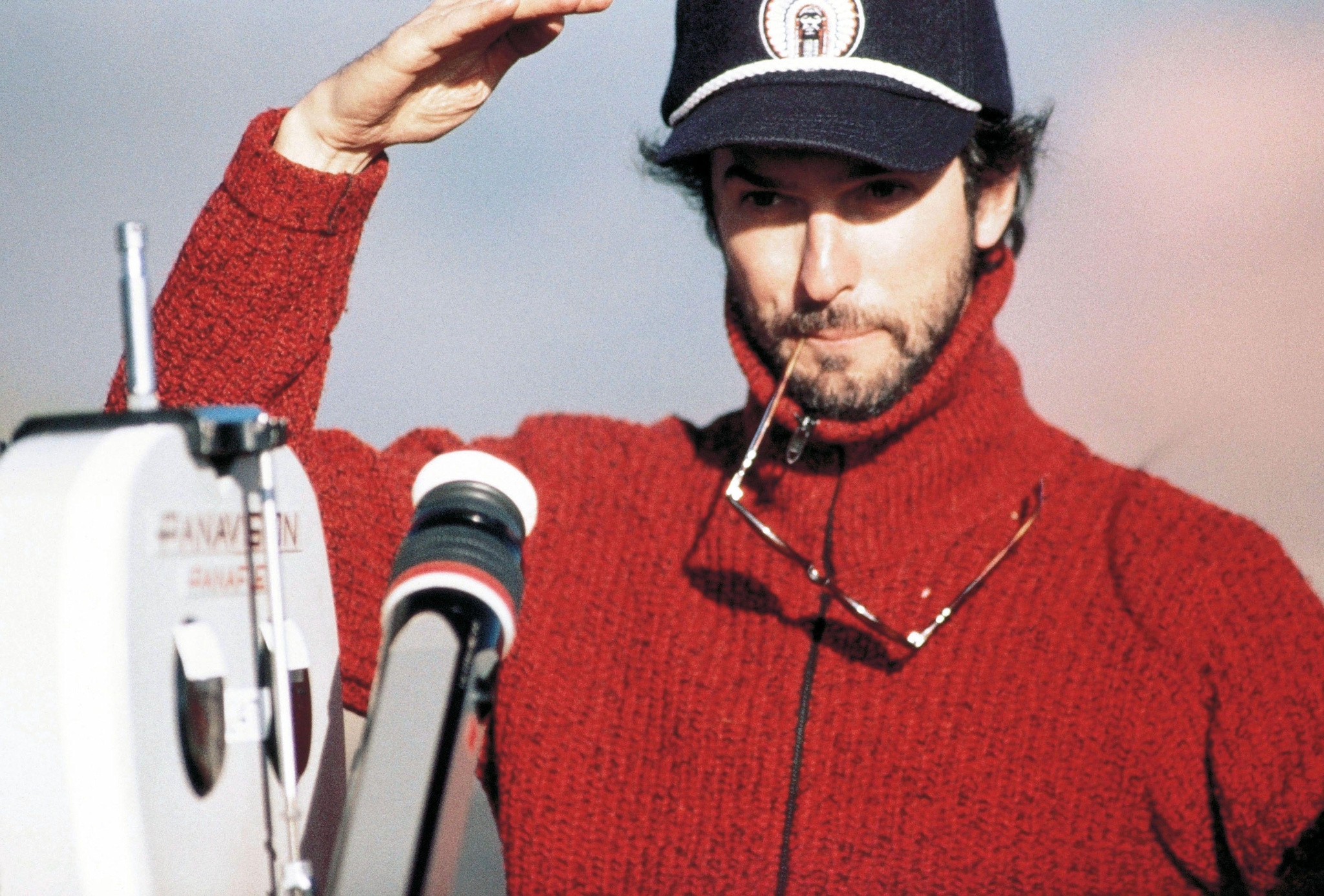

Director Martin Brest on the set of Midnight Run (1988)

“Let’s talk about great actors,” Brest says, when I ask about his experience working with two of the most important screen actors of their generation—De Niro and Pacino—on back-to-back projects. ”Each one is different, and each one figures out their own way to flip their reality so profoundly that their performance triggers in the viewer a sudden insight into human behaviour that they may never have had before. And those are the greats. De Niro and Pacino? They’re gods.” Brest’s philosophy is to approach his films through the eyes and heart of the lead character—a true actor’s director. “That’s why you look at Eddie Murphy in Beverly Hills Cop and think ’No one else could have played Axel Foley.’ But it’s because, in my movies, the actor’s interpretation of the role is influencing at every turn the shaping of the film, and in response, the film tries to squeeze out the essence of what they have to offer.”

The filmmaker has a limitless splen-dour of anecdotes about Pacino on the set of Scent of a Woman—story after story of arguably the greatest actor of all time being, well… the greatest actor of all time. He recalls walking Pacino through a scene where the blind Slade walks across a busy street unassisted. “We’d called in all these stunt cars to make sure he could cross and not get hit. You have to commit when you cross, you can’t hesitate, you have to leave your fate with the drivers. I said ’Al, take a look at this’ and I took his little blind man’s cane and I walked into the traffic, with all the cars screeching around me. I looked around and said, ’Isn’t this great!’ and he looked white as a sheet. He said ’You almost got killed!’”

Once Brest explained the concept to Pacino, it was his turn. He crossed without a hitch, but accidentally tripped into a nearby garbage can on the other side of the road. Of course, he stayed in character, turning an unusable shot into a window through which you can more deeply gaze into his character. “I got down on my knees in the middle of Park Avenue and I raised my hands to the heavens and screamed, ’I’M THE LUCKIEST FUCKING DIRECTOR IN THE WORLD’.”

A still from Scent of a Woman (dir. Martin Brest, 1992.)

If Brest is Scent of a Woman’s architect, then Pacino is its alchemist, ready at a moment’s notice to take the unexpected and make gold dust out of it. Brest’s favourite example of this occurred on the very first day of shooting, during the very first scene they shot of Pacino in character, which he describes as one of the single most miraculous moments he has ever experienced on a film set. The scene takes place near the end of the movie, after Slade delivers an impassioned monologue to Baird’s disciplinary committee in defence of Simms, on the verge of expulsion for his refusal to name the students responsible for the prank on Headmaster Trask. Leaving the assembly, they meet another teacher, who takes a liking to Slade. The shot is a tight closeup—the two have a conversation, Pacino walks out of frame, and the scene ends. Waiting just outside of the frame are the crew: production assistants, boom operators, extras waiting to enter the frame, you name it. “I guess I wasn’t clear with the cameraman that he doesn’t pan when Al leaves the shot, because on the very first take, he exits and the cameraman pans with him. I’m thinking, ’Whatever, it’s not going to be usable’. But, I’m looking at the monitor, and I’m thinking, ’OK, well, this kind of looks nice… OK, well, wait a minute, this looks spectacular’, and the next thing I know, I’m waving at everyone to get the fuck out of the way for Al and the camera. Everybody’s running with their chairs, the assis-tant directors are abandoning their extras and letting them run wild.” Brest keeps the cameras rolling, just barely clearing production in time to make room for the approaching Pacino and O’Donnell. “And then Al starts talking, and he says, ’Don’t tell me, Charlie… 5 ’7 “, auburn hair, beautiful brown eyes’ and he starts to describe the woman. It was not rehearsed. He just went into the role of the character, and he would have gone home in character if we had let him.”

To Brest, however, Pacino’s true genius lay in his deep understanding of the filmmaking process, to the degree that his performance as Slade took on an almost interdimensional qual-ity. The scope of Pacino’s foresight was so great that it reached beyond the film shoot and into the editing room itself, with the actor leaving winks and clues in his performance that he knew would influence Brest and his editors in post-production, like an act of celluloid time travel. “If you watch his dailies, he’ll stop in the middle of a take, and go back and repeat it a little bit differently. If you don’t understand editing, that might look goofy, but in the editing room, we know, and he knows, that he can hit a spot that wouldn’t have been possible without playing out the process all the way through.”

Brest recalls once assembling a series of Pacino’s takes, marking spools of film with a grease pencil and leaving his editor to manually cut them together into a full sequence. When he returned to view the final product, it didn’t feel quite right, despite his editor’s insistence that he used the takes that were marked by Brest himself. “I didn’t believe it,” says Brest. “So we took out all the reels of film and, sure enough, the marks were all there where I had left them. Then I noticed something: that after delivering a line, Al does something that’s more important than the line. He would purposely leave a pause after the dialogue that was critical to the perception of what was happening in the scene. But the editor had cut that out, and it made the reception totally different. He went back and put the pauses back in, and it was fantastic. I said to Al, ’What, are you going to tell every director you work with to tell their editor to watch out for those little pieces of gold?’” Brest chuckles, before continuing. “He knew, as I do, that the takes you pick, the pauses you decide to leave, the juxtapositions of different performances, create little emotional moments that aren’t visible on screen but you can feel them in your gut.”

Al Pacino and Chris O’Donnell in Scent of a Woman (dir. Martin Brest, 1992)

We spend considerable time, also, gushing about the performance of a then struggling actor who would go on to become one of the most revered character actors of his generation. “Philip Seymour Hoffman was so unbelievable that I immediately said, ’Oh my God, I’ve just discovered the next great actor.’ He just came from another planet.” The 25 year-old Hoffman, who, at the time, was working in a deli and had featured in a few bit roles here and there, was originally overlooked for the part of George Willis Jr, the privileged, spineless son of one of Baird’s investors, and the moral opposite of Simms, who the film makes a point of embodying working class values like integrity, empathy, and respect. Of course, once Brest saw him in action, it was undeniable: a fully formed performer out of the gate, making the kinds of choices as an upstart that even the most seasoned actors wouldn’t think to consider.

Brest tells me that one take from Hoffman was so passionately delivered that it stunned the cast and crew into silence—unfortunately, it didn’t quite fit the tone of his character, and was left on the cutting room floor. “Phil’s performance in that wide shot was one of the most intense, balls-to-the-wall performances I’d ever seen. It was fucking amazing, and the most extraordinary thing he did on the set the entire film. But it was the wrong performance—it was fucking amazing—but it was from another movie. So I told him to play it again, and this time to focus on not ripping his heart wide open in the long shot. Save that bit of your soul for when we move in tighter. It’s an extraordinary piece of footage, wherever it is, probably residing in some salt mine somewhere.” Nevertheless, the footage that did make it to the final product was of such high calibre that it caught the attention of a pimple-faced young director named Paul Thomas Anderson, who wrote the character of Scottie J in Boogie Nights (1997) specifically for Hoffman, in turn leading to a longterm collaborative relationship between the two generational talents that continued until Hoffman’s early death in 2014.

Phillip Seymour Hoffman in Scent of a Woman (dir. Martin Brest, 1992.)

While Hoffman was a scene stealer from the outset, 22-year-old Chris O’Donnell thrived in his tenderness. “I hope Chris doesn’t mind me saying it, but he looked crucially virginal. Bo used to have an expression, when somebody is ’without side’, meaning without any hidden agenda. Chris had that thing where as hard as you looked, you could only find innocence.” The role of Charlie Simms was the hottest ticket in town, and reportedly everyone from Matt Damon to Chris Rock auditioned for the chance to star opposite the great Al Pacino. Going toe-to-toe with the man considered to be one of the two or three defining screen faces of a generation would be intimidating for any actor just starting out—a lamb sparring with a lion—and Brest tells me a story about how a particularly courageous take from O’Donnell became lost in the ether.

In the scene, Simms tearfully attempts to convince a depressed Slade not to commit suicide, with the conversation escalating in emotional intensity until the point where Slade has Simms bent backwards on the dresser with a gun pressed to his neck. “Chris really tried very hard, it was his roughest scene in the movie. We did it over and over again, and he was burnt out, his back hurt, his soul was beat.” But Brest still didn’t have quite what he needed, emotionally, to move on. Trusting that O’Donnell had something special buried somewhere in his reserves, he asked the actor for one last take. “We did the scene, and Chris was so emotionally charged at this point, that after he stood up he started crying. It was this sincere emotional flood—the dam just burst. I thought, ’Oh my God, this is it’, and I glanced at the monitor and the camera was out of focus. I looked back at Chris, achieving a lifetime high of acting, and I looked back at the cloud on the monitor, and I looked at the assistant cameraman, and burnt a fucking hole in his head. The piece of film was Chris’s best piece, and it was utterly unusable. I was suicidal for months. It tore my heart out.” The turmoil Brest felt at having lost the take ran so strong that he attempted, several times over several months, to make contact with the CIA, whom he thought must have super technology that could increase the resolution of the blurry image. “We never had a response.”

Listening to Brest talk is a pop-the-hood experience; an illuminating glimpse into the tragedies and miracles that occur while making a film. Thematically, Scent flickers with the same genetic coding: what is lost and found: the tragedy of losing one’s sight and the miracle of regaining one’s spirit. With the theme on my mind, I ask Brest if he still feels the itch to return to filmmaking after so many years out of the fold. He replies as if he never truly left. “There’s a project I’m madly in love with that I’ve been trying to get going for a while. It’s an adaptation. It’s been a little challenging because I’m in director jail… more like director supermax. It’s a dangerous thing for an older director to have a passion project. But this one’s a beauty.”

Between shooting scenes from the set of his latest movie, Al Pacino himself found a few moments to share with us some thoughts on his time making Scent of a Woman. The actor didn’t originally didn’t intend to be a part of the film, owing to a personal reading of the script. But that changed, he tells me, when he read it with other members of the cast. “In the old days, when you had your doubts about a script, you would have a collective reading,” he explains, “meaning to read it aloud with the other actors. I had a reading. It went well. So I opted to do it.”

Of director Martin Brest, he had nothing but the highest of compliments. “He’s a deep, wonderful person with an innate and direct tie to empathy. He’s a beautiful director and a better man.” When I ask about how he achieved the illusion of blindness, so convincingly that it astonished even Brest, the great actor replied, “I don’t know how or why I was able to come up with it. It was relatively easy for me; through my memory of people I’ve known throughout my life and what I saw in life from time to time. I must have absorbed it, and been able to access that somehow. My imagination was able to suit up and play that person. It gave me a lot as an actor. Somehow it brought more out of me, to play someone with an inability to see.”