Along with slip dresses, tube tops and other things I can’t now believe I had the courage to wear in the 1990s, transparent clothing is having a moment. It has been hard lately to avoid the trend in stores and on the red carpet, where Dua Lipa, Rita Ora and Florence Pugh have worn see-through styles (‘Another day, another jaw-dropping sheer gown’ said Harper’s Bazaar of the latest body-celebrating appearance by Pugh at the BoF 500 Gala) while in Paris this week. Sheer and transparent pieces including silk blouses and see-through dresses in both black and jewel tones dominated Yves Saint Laurent’s autumn-winter 2024 collection.

This YSL collection has timed with an exhibition in Paris which explores the key role that diaphanous creations played in the late Yves Saint Laurent’s body of work. The exhibition, in the premises of his former haute couture house in Paris, follows neatly from a collaborative exhibition staged last summer at the Museum of Lace and Fashion in Calais, which focused similarly on transparency as a form of artistic expression.

The late French fashion designer, who became Christian Dior’s assistant at the age of 17, in 1955 and head of the House of Dior on the couturiers’s sudden death two years later, had enormous influence. After opening his own fashion house on the rue de Bellechasse in 1962, the so-called ‘Pied Piper of fashion’ put women in peasant-style, metallic and most famously, masculine clothes. His double-breasted suit and ‘Le Smoking’ tuxedo suggested glamour and power without sacrificing comfort. ‘Blazer, trousers and suit. They’re so functional,’ said Saint Laurent, ‘I believed women wanted this, and was right.’ Worn by celebrities including Bianca Jagger, Lauren Bacall and Nan Kempner, they became instant classics.

Saint Laurent debuted his first sheer creations—a black organza blouse and a chiffon dress with zig zag sequins in all the right places—in 1966, drawn to these feather-light materials, along with lace, tulle, because they encouraged movement and expression, and because of their inherent contradiction to the function of clothing itself: to cover, conceal and protect.

Saint Laurent hoped his sheer designs would grant women a means of asserting their bodies on their own terms; as subjects of their own story rather than objects of desire.

The exhibition also considers Saint Laurent’s inspirations. Lace in the paintings of Francisco Goya, for instance (in the 1960s, the couturier copied Goya’s paintings in his sketchbooks and they reappear in his collections of the early 1970s and in 1981); Francis Picabia (who made a series of ‘transparency’ paintings between 1927 and 1932) and Man Ray (who in the 1930s used a double exposure that revealed the model’s body as if it were X-rayed).

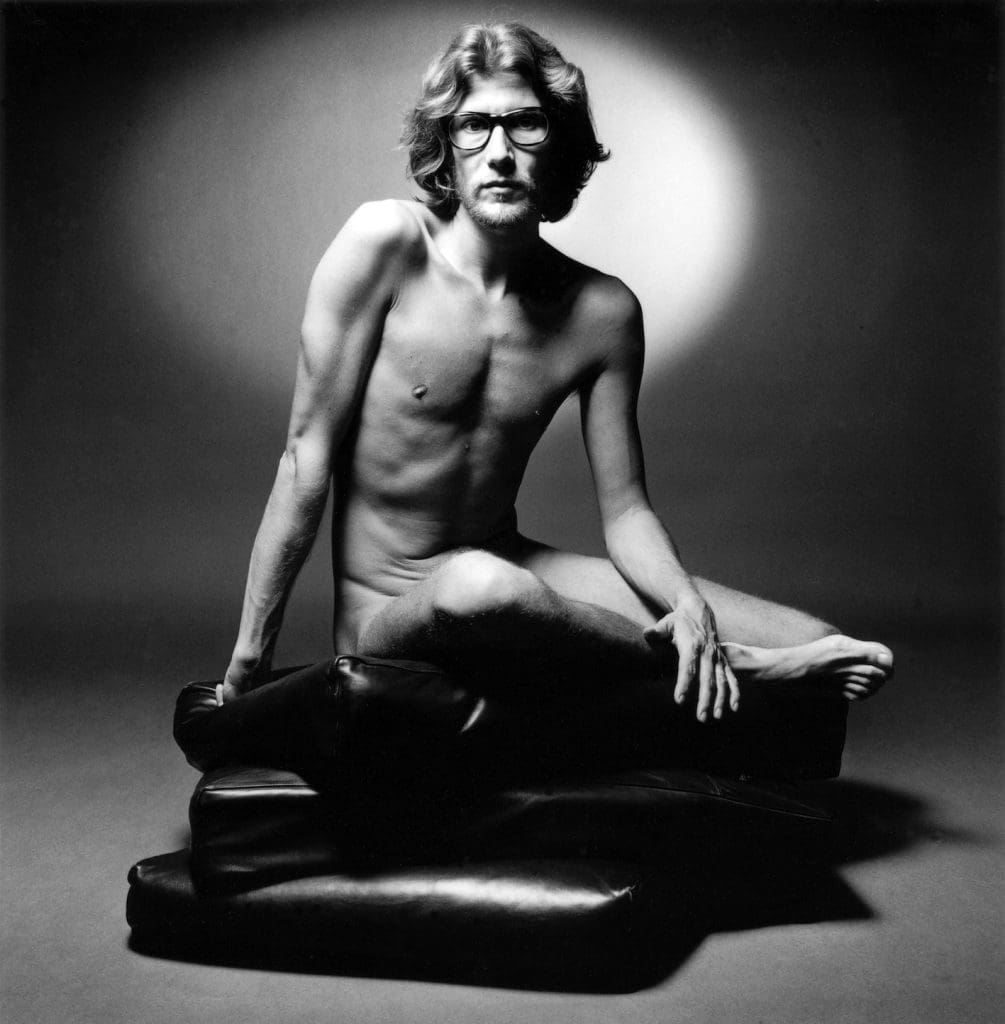

Nude portrait of Yves Saint Laurent for the advertisement of his first eau de toilette Pour Homme, Paris, 1971. Photograph by Jeanloup Sieff

© Estate Jeanloup Sieff

Indeed, transparent clothes have quite a pedigree. Muslin appears in the writings of Ancient Roman courtier Petronius, and in the 18th century, a particularly fine, rare variety from Dacca (now Dhaka), India (now Bangladesh) was worn by Queen Marie Antoinette, Joséphine Bonaparte and Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Sheer dresses over slips were also popular in the 1920s and 1930s, long before Kate Moss wore her now iconic silver version to a party at the London Hilton in 1993, igniting the sheer craze all over again. Saint Laurent’s pieces from this decade include a blue evening dress and a black dress with lace cut-outs.

Moss’s dress was a body-skimming bias-cut, but even when sheer fabric is cut to drift or balloons around the body, it cannot help but emphasise what lies beneath. Arriving at the peak of the Swinging Sixties, then, and as the women’s movement and initiatives such as ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’—which encouraged women to take full ownership of their bodies—were gaining momentum, Saint Laurent’s transparent look tallied with, and tapped into, that era’s spirit of sexual freedom.

Saint Laurent, who was—the curators are careful to point out—quite willing to put his own body on display (in 1971 he appeared nude in a photograph by Jeanloup Sieff for the brand’s first male fragrance, Pour Homme) hoped his sheer designs would grant women a means of asserting their bodies on their own terms; as subjects of their own story rather than objects of desire. YSL’s co-founder Pierre Bergé explained it best, ‘Gabrielle Chanel gave women freedom. Yves Saint Laurent gave them power.’

Sheer: the Diaphanous Creations of Yves Saint Laurent is at the Musee Saint Laurent until August 25 museeyslparis.com