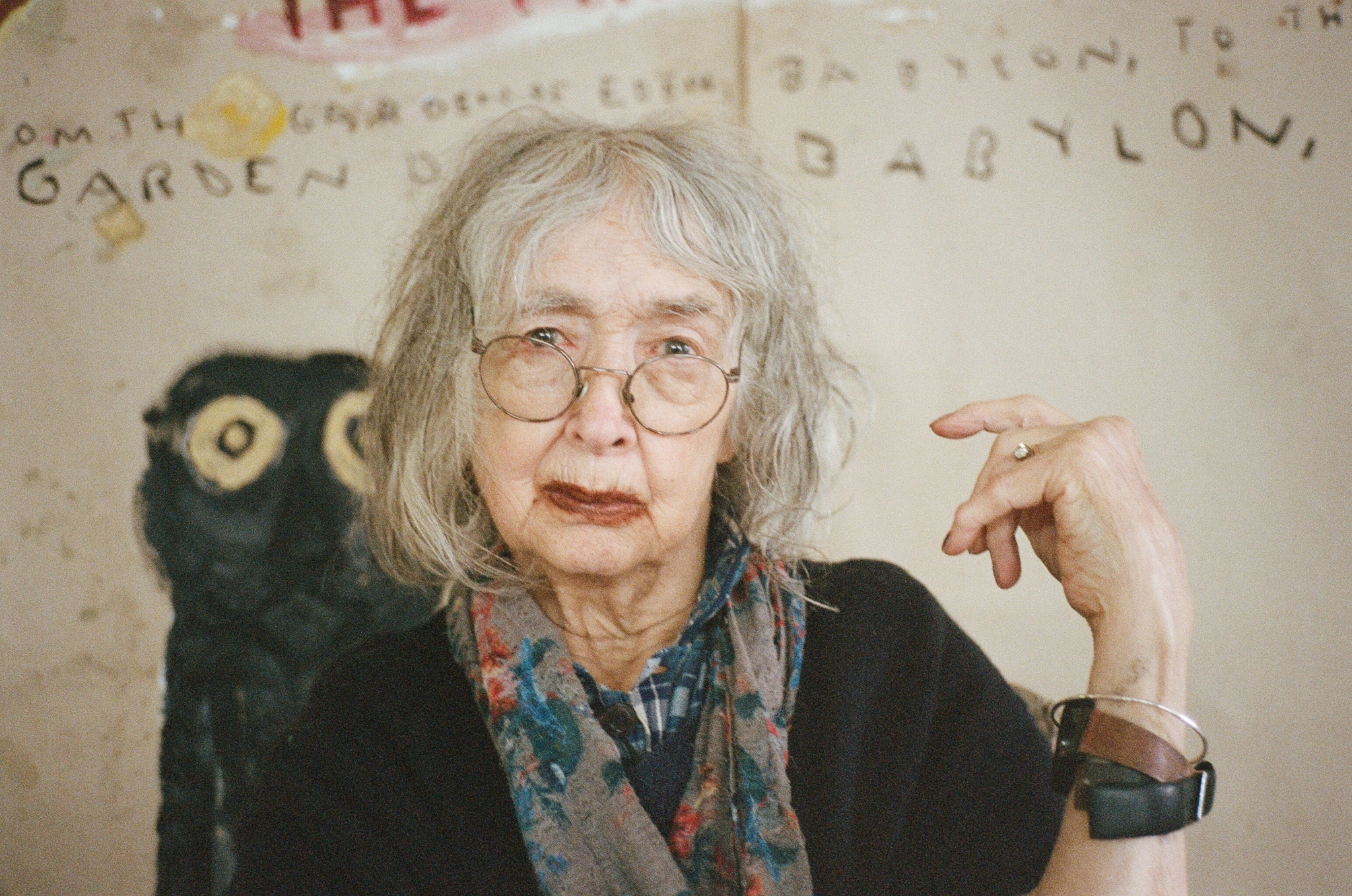

In Faversham, Kent, the artist Rose Wylie resides in a world removed from our own, surrounded by her art and nature. Lucy Davies pays Wylie a visit to learn more about her extraordinary life. Photography by Fatima Khan.

The garden at Rose Wylie’s house in Kent is a long rectangle that juts snugly into a field. It is a strange place, like something in an E Nesbit story, dotted with crumbling stone urns, awash with greenery that no one ever gets around to cutting, and peaceful but for the birds chirping happily and noisily in the trees.

Wylie leads the way methodically, more naturalist guide for the moment than world-renowned artist, pointing out crescent-shaped dents in the undergrowth as we go. “The cat jumps into it, you see. This one looks like the continent of Africa.” She walks the garden every day, she tells me, though usually late, “when the shadows are good,” and the primroses release their pleasant fragrance. “The evening light is marvellous on the pale yellow,” she adds, “and I do like yellow.”

Wylie, who came to prominence in her seventies after decades of relative obscurity, will be 90 in October. She is spry for her age and precise in conversation, with the clipped vowels of a character in Brief Encounter (1945). A little formidable when the mood takes her. She takes great pride in her plants—the hawthorn, hazelnut, willow, and wild cherry, an unusual periwinkle that sprouts dark purple flowers. The soil is good here: thousands of years ago, the Romans grew grapes in the valley, which slants behind the garden towards a grey sky, March-like in July.

Rose Wylie shot by Fatima Khan

Wylie moved into the house with her husband—the late Roy Oxlade, who was also an artist—and their three young children in 1969. Its transition from domestic setting to workspace, with one paint, book, and canvas-filled room opening on to another, was gradual but efficient and today not an inch is wasted in pursuit of her art. Wylie even lays crumpled tissue paper on her sofa “to add a bit of white” and has stuffed the hearth with shrivelled flowers because, she says, “I’m very, very fond of leaves.”

Still, none of it is a patch on upstairs, which is given over to her studio and a sea of torn and scrunched-up newspaper studded with half-empty paint tins and multiple Pritt Stick tubes. The old plank floor looks as though it is strewn with confetti, covered in dots and splotches of colour. Ditto the radiator and the light switch.

“It’s what happens when you paint and you’re not constantly clearing up,” says Wylie, blithely. “And most of it’s paper, which I use to wipe brushes. There are no cigarette ends, no bacon rind.” Intermittently, the rumble of a passing car floods the room. “I like outside noise. It’s the opposite of being dead, or in hospital.” Until turps and white spirit fumes drove them next door, Wylie and Oxlade also slept in here on a mattress, in a shelf-like crawl space under the eaves. Today the beams above it are a tangle of curlicue creepers and leaves, some bleached by age, some still bright green. “Look, it’s flowering,” says Wylie, reaching for a stem of jasmine.

The house dates from the 17th century, a time of civil war and Puritanism. As its red bricks were being laid, three women were hanged from a tree for witchcraft in the nearby village of Faversham. Inside, the past feels near, with clumps of the horsehair that stiffened the plaster coming loose from the sloping walls. The men who put it there, all those years ago, would have been thought old at 50, but here Wylie is, still painting floor-to-ceiling canvases.

In the old days, she liked to make them on the floor. “Because I thought it was the opposite of what the big boy artists do. You know, on walls or on easels. And also it was like cleaning the floor, the scraping,”—she mimes the action for me—“I used to walk and crawl on them too. I thought it gave me a kind of friendship with the painting. But somebody reminded me it’s not a good idea to get paint in your toe nails, and then I had hip replacements, so no longer.”

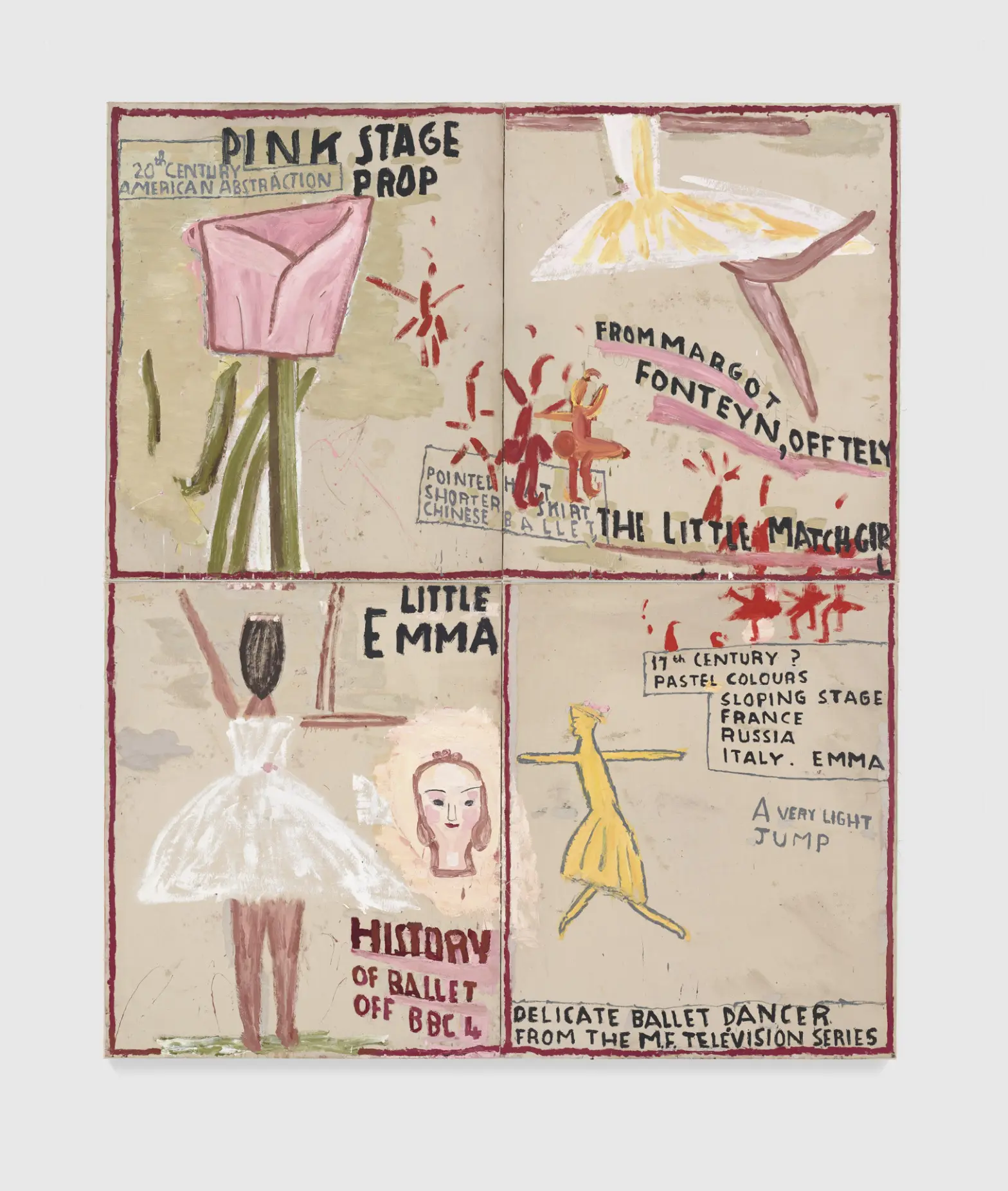

We have met today because Wylie is about to have a star turn at Frieze London, where David Zwirner Gallery will present a selection of her new paintings in a space dedicated just to her. The gallery has represented the artist since 2017, shortly after she won the John Moores Painting Prize and the Charles Wollaston award, and was elected a Royal Academician in quick succession. Four of the paintings that will be on show are still tacked to Wylie’s studio walls. Two, featuring a heavily outlined moon and the long, strong shadows of Giorgio de Chirico, were inspired by photographs she saw on Instagram, of sculptures in an intriguing-sounding abandoned city in southern Africa. “I don’t know anything about it,” she says, heading me off at the pass. “It was not the facts, but the look of it.” Another was triggered by the ballerina Margot Fonteyn and the 18th-century tinted engravings. It’s from a series of four concerning the history of ballet, though Wylie is not, she says “a ballet person… The music is never quite as good as late Beethoven.”

Viewers fall for Wylie’s paintings because they are so full of self and ebullience, but it is her ability to create collisions between wildly disparate things, and importantly how she does it, that is remarkable. Her subjects are sifted from pop culture, history, and her own experiences, fed both by the vertiginous mass of images she saves hugger-mugger on her computer home screen, and a fierce, wide-ranging intelligence.

Rose Wylie, Ballet Backdrop, 2024. oil on canvas (4) four parts. © Rose Wylie. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

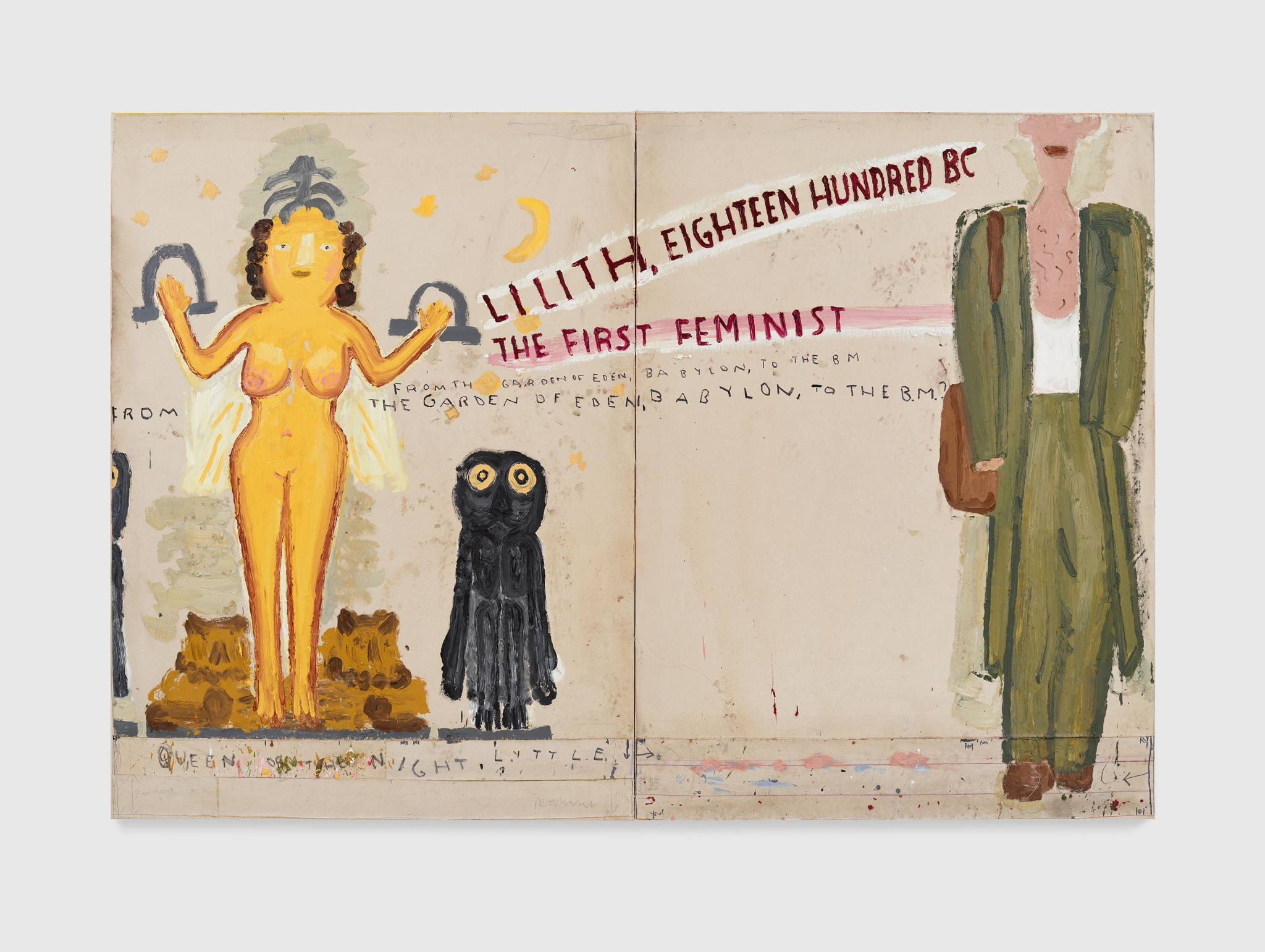

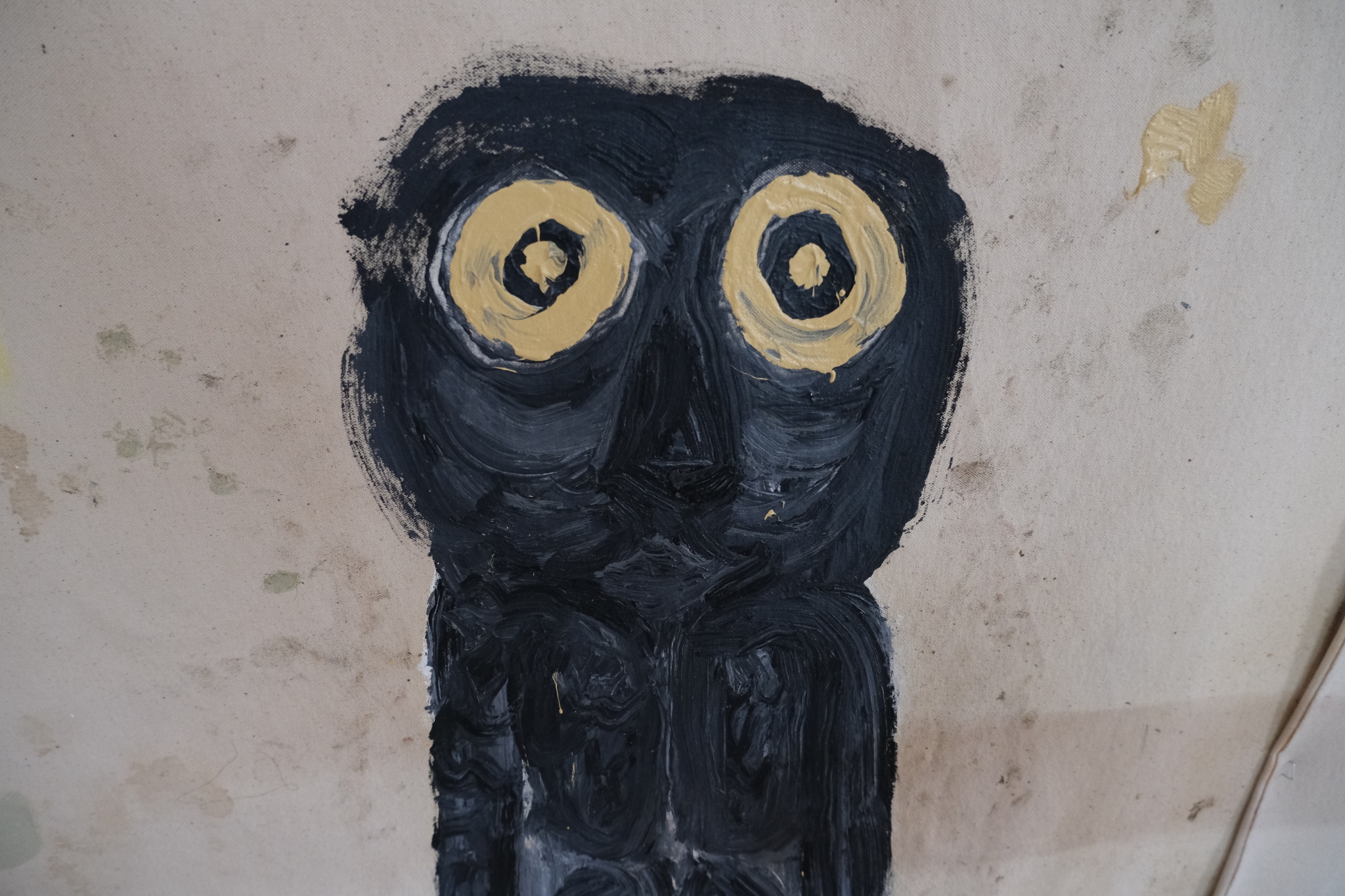

Take the largest of the new paintings, which covers the whole of one studio wall and has extra strips of canvas stuck to its bottom edge to accommodate Wylie’s composition. “I couldn’t fit his feet,” she says in explanation—“he” being the moody runway model in a suit and low-cut vest on the right-hand side of the painting. She has christened him “Gucci boy”. To the left is Lilith, first wife of Adam, who chose to leave Eden because she was treated as his inferior and later became a winged spirit or a malevolent demon, depending on your source (Sumerian, Greek, Michelangelo, second-wave feminism—there are a few). “She’s a smashing subject, and she’s been whitewashed, because history, scripture, the whole stuff, it’s been written by men.” Wylie found her, she tells me, when a drawing she had made of a plaque in the British Museum chimed with a Wim Wenders film, of all things.

A few days before my visit, she posed in front of Lilith for the photographer Juergen Teller for a fashion shoot. They put her in a floor-length leather coat, which she thought made her look like a monk, and another in gold lamé. “That must be the October look,” she says dryly, peering over the tops of her glasses. “I first thought I looked like a Zurbaran monk, but then I made this transformational jump, and I became like Michaël Borremans’ paintings, which I think are great. The coat had morphed. What a look. Just marvellous.” Later, I found it piled over the clothes basket, in the bathroom, her downstairs dressing room and close at hand for putting on. She loves it.” Wylie has always been interested in what people wear. As an art student, she was “very outlandish”, cutting up her clothes and sewing them into new forms, scrubbing the colour off her leather shoes with Vim, a gritty cleaner. “I put white over my face, and yellow all over my hair. I was unusual, an early punk.”

Was she like that as a child too? “No, completely the opposite. I did exactly what my parents wanted. They were Victorian; they didn’t bother with what I liked. But I have no criticism against them.” Wylie grew up in Hythe, Kent, and later in India, where her father was the director of ordnance—civilian rather than army. Her memories of those years are hazy: a picnic, her cat running away, the paintbox with which she drew golden crowns and dragon scales in her parents’ novels. The family moved back to Britain during the Second World War. A large canvas in her dining room describes doodlebugs floating in a banana-yellow sky above Bayswater. At 17, she toyed with becoming a film star—“I liked the big image”—and retains strong opinions about actors. She prefers the “metaphysical beauty” of Greta Garbo, Isabelle Huppert, and Emma Stone, she tells me, to the big-eyed voluptuousness of your Claudia Cardinales and Gina Lollobrigidas. Last night she watched a documentary about Marilyn Monroe, followed by the actress’s 1957 film The Prince and the Showgirl.

“It sounds as if you stay up quite late.”

“I stay up very, very late. Sometimes I go to bed at three, sometimes three-thirty. It’s dark. There’s no noise—the village goes to sleep at half past ten—it’s a good time to work. But I never get up before nine.”

At 18, Wylie went to Folkestone and Dover School of Art, encouraged by her mother: “She said that you never know when your marriage is going to break down, whether your husband’s going to die—so it’s useful if you’ve a backup.” Wylie smiles. “Quite good, isn’t it? But I was her seventh, so she’d got on a bit… They didn’t much like what I made though. I think some parents say, ‘Oh, that’s lovely’ and put it up in the house. They didn’t do that. But they didn’t oppose it.”

Rose Wylie shot by Fatima Khan

There were only two women on the college staff, “one fabric design, the other fashion,” says Wylie. “All the artists out there at the time were men too—Picasso, Léger, Picabia—not a woman in sight. The men used to sneer and say, ‘You’ll get married and have children’.” Dispiriting, you might think, but “no, not at all. I think it was a carrot. Remember I was the youngest, so I was used to people bossing me about, not listening to a word I said. I was negligible, just a cog, a student who’d be giving up anyway. So no, I didn’t mind.”

Afterwards, Wylie studied teaching at Goldsmiths, which is where she met Oxlade. “He stalked me,” she says, leaning back into a paint-encrusted wood chair, a cup of tea cooling in her lap. “He told me he saw me coming out of the V&A—I’d been doing brass rubbing, which is what we were encouraged to do—and I didn’t have a handbag, which to him was amazing, because women, he thought, liked prams and dressing tables and jewels and handbags.”

Oxlade recalled the same moment in the 2015 documentary film Rose & Roy: “She always had a kind of aura about her, the way she walked around,” he said. “I was rather stunned. I think about two weeks later I asked her to marry me, and she said yes, so there it was.”

A tutor at the Royal College of Art (RCA), where both Wylie and Oxlade ended up as mature students in the late 1970s, recalled the relationship as “an extraordinary love match, an inspiring and touching union of restless intellects and imaginations”, and that the couple “strolled about hand in hand, deep in animated conversation”.

Oxlade died in 2014, just as Wylie’s career began to crest. His striped and spotted neckties still hang over the bedroom mirror, and photographs of him are propped everywhere in the house, including on the kitchen dresser, among the jars of semolina and mung beans, and a mug emblazoned with “hello c***y”. For most of her life, Wylie didn’t swear at all—“my mother and father hated it”—but in her later years she has taken it up with a vengeance.

Rose Wylie and her cat in front of: Rose Wylie, Lilith and Gucci Boy, 2024. oil on canvas. DIPTYCH. © Rose Wylie. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

As is well-known, Wylie put painting aside when she had children. “People often say to me, do I feel angry because I didn’t paint while my husband did? But the answer is no, because I think children are important and that you have to be available and to talk to them, and if you paint, you can’t. You want to get back to your painting, so the children become a nuisance, an irritation, marginalised, and I didn’t want to do that. I spent time with them, I talked to them about books and about trees. I still talk to them about my work.”

Still, between graduating from the RCA in 1981 and the flood of accolades and attention that came in her seventies was a long period of invisibility, from which she has not emerged unscathed. “I think being left out, being excluded for years and years and years was a bit… it was a bit of a shame,” she says. “People used to look at my paintings and go ‘uh huh’. They didn’t know what to say. So they marginalised them. They gave them no place.” She recently suggested Uh-huh-huh as the title for an exhibition of her work in Switzerland, “though the curator rightly turned it down. She thought a deprecating noise might not be the same in other languages.”

In the late afternoon, we are standing in the kitchen, its door flung open to the garden, and Wylie is opening wine. The clouds have grown and darkened in the past few hours and as we sit to eat, the rain arrives, sliding across the glass panels of the ceiling in watery sheets. “I didn’t swear much, did I, in the interview?” says Wylie, a little disappointed. “When I grew up only men swore, and at art school only men drank wine, huge amounts of it. At the time, it seemed like power. It was vivid and what you had to do. But so much non-mainstream art was marginalised or left out,” she says. “I think that’s why I liked her—Lilith. I think she’s terrific. Made at the same time as Adam, made from the same clay as Adam and was banished from Eden by Adam, or left by herself, because she was not submissive. It’s quite a story,” Rose explains. “She was introduced to me by Anselm Kiefer in the film Anselm (2023). I don’t usually plug the subject-matter in my paintings. But here, it’s quite something.”