“It’s the work that remains,” said the Feminist Surrealist Penny Slinger, explaining that her work—collages, installations and film— now in a breathtaking exhibition, An Exorcism: Inside Out, at Richard Saltoun Gallery at London’s Dover Street until September 7, arose from her romantic and creative relationship with the filmmaker Peter Whitehead, who not only instigated the work but graciously, and unusually, served as muse.

Whitehead sadly passed away in 2019, but for the first time, since its inception in 1969, the work is shown just as Slinger wanted. And what a glorious wonderland it is! As the writer/musician/artist Viv Albertine said upon seeing the show, “I found it extraordinary, especially for the times. I went to art school about seven years after Penny and I wasn’t aware of (or taught about) women making work like that.”

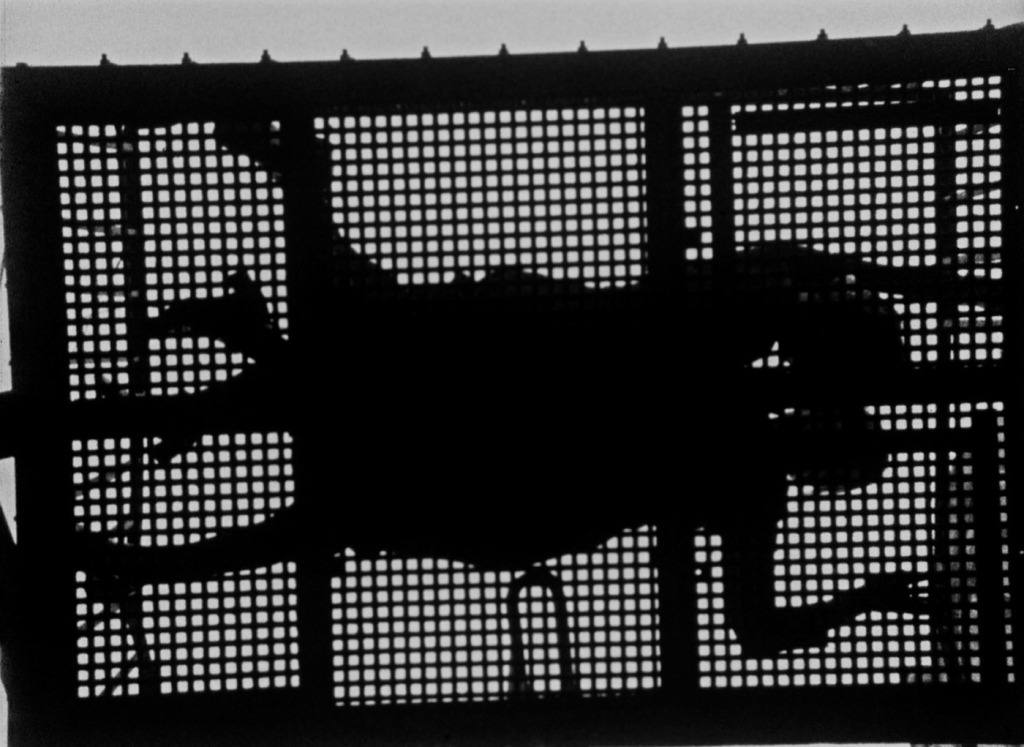

from An Exorcism series, 1969-77, © Penny Slinger, Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery.

Inspired by her project in 2019, when she took over the iconic Maison Dior (the couture atelier) on Avenue Montaigne for the Dior couture show, Slinger has created an “analog immersive experience” at Saltoun. The gallery is an installation of rare gorgeousness filled with photographic collages (in bespoke frames specially designed by Slinger), film and lightboxes set against life size tree branches, roots, foliage, clouds and the sea collaged on the walls, floors and ceilings of the gallery. We are enveloped not only by the beautiful imagery but also, at times, by Slinger’s lilting voice from the film. The show coincides with the re-publication of the book, An Exorcism: A Photo Romance, which is also, for the first time, presented as she originally intended—with images and accompanying text. It is available from Fulgur Press as a beautiful hardback, and as a limited edition of 49 handmade deluxe books in crushed morocco leather, including a signed print.

The text—lyrical poetic passages—written by Slinger, challenges the archetypical stages of a woman’s life from infancy to adulthood in a thrilling Surrealist heroine’s journey and imbues it with power—often (unapologetically) sexual. This is glamorous feminism with both mind and body firing on all cylinders. As often would be the case throughout her career, Slinger is her own central muse, and she is both subject and object: “Throughout the history of art, I saw the role of woman as muse—usually through a man’s lens. I wanted to refashion the role of the muse through my own lens. I wanted to be my own muse. I felt I could be more ruthless with my own image than with anyone else’s.”

The background of the work is fascinating story in itself. In 1969, Slinger was a promising young artist barely out of Chelsea art school exhibiting in the “Young and Fantastic: Where is Surrealism Now?” show at the ICA. She was visiting Michael Kustow, the ICA director, when he asked that she welcome his friend who was expected to arrive any moment while he stepped away briefly. The friend was the film director Peter Whitehead, ten years Slinger’s senior and already a well-known figure, having pioneered what became known as the music video, working with the likes of Pink Floyd and the Rolling Stones. “Peter was so handsome,” Slinger said. He offered to drive her home to Notting Hill in his red MG. “When we arrived, Peter put his hand on my shoulder, and I thought, Oh…hell, because I knew we had to be together,” recounted Slinger laughing softly. And thus, the door to An Exorcism was opened.

Whitehead took Slinger and her friend, Su Fraey to visit Lilford Hall, a rambling, oneiric, gothic country pile in the Northamptonshire countryside as a possible venue for a film project. He had stayed there before when a student and made paintings. They tracked down the owner, Lord Ian Winterbottom, who was taken by the two “actresses:” Slinger and Fraey. Who wouldn’t have been captivated by Slinger, a ravishing gamine beauty of the swinging Sixties and Fraey, her equally attractive pseudo-doppelgänger, with matching crops courtesy of Vidal Sassoon? Winterbottom unsurprisingly allowed them to have the run of the place, to film, photograph and experiment.

Lilford Hall was everything Whitehead had promised—romantic, haunting, inspiring in the way that only a crumbling Stately English House—still recovering from the devastating war and adapting to a new economic landscape—could be, and perfectly in keeping with the aesthetics of the times à la such films as Performance and Suspiria. On the grounds were twisted ancient trees, roses, and vines climbing high stone walls, while inside were endless empty rooms of faded luxury inviting the imagination.

The group rented a nearby cottage and stayed for several weeks to film what became “a psychodrama with ourselves as the participants.” Slinger describes the experience:

from An Exorcism series, 1969-77, © Penny Slinger, Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery.

Su and I made shapes of our bodies as silhouettes on the fire escape, we stood sentinel in the cage of the lift, I entwined myself in the creepers while she fondled herself provocatively in the window behind me. We played “Blind man’s buff.” We appeared tied up or hanging in cupboards, naked in empty baths. I ran naked in the empty cages, peering through the bars. It all felt contiguous with my previous endeavors and with the brand of symbolism and imagery I had been developing….

Photographs were taken of the vast atmospheric rooms as well as the grounds. When Slinger developed the photographs, she created a double set of prints with the idea that both she and Whitehead would independently create their own series of collages in the spirit of Max Ernst, and then compare.

Slinger’s art school thesis had been on Surrealism and Max Ernst, in particular his famous collage books, Une Semaine de Bonté and La Femme 100 Têtes. Seeking out someone who knew about Surrealism first-hand in Britain (where it was not so well known at the time), she enlisted the help of her friend, the Right Honorable Robert Erskine to meet Roland Penrose, who in turn, became her patron, and introduced her to Max Ernst in Paris. When Penrose came to her diploma show and saw her sculptures and the 50% The Visible Woman poems and collages, he was impressed: “Oh my goodness, Penny darling, I didn’t know you made such beautiful things too,” and recommended her work for the ICA “Young and Fantastic” exhibition.

from An Exorcism series, 1969-77, © Penny Slinger, Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery.

Soon after the trip to Lilford Hall, Slinger started on the collages, but Whitehead got distracted by falconry and a writing project. Slinger then got involved in Jane Arden’s Women’s theatre group, the first all women theatre group, and shifted her attention away from the collages. The two-year involvement with the women’s theatre group, culminating with the shoot of the film, The Other Side of the Underneath, “acting out Jane’s psychosis,” became a traumatic experience for Slinger and led to the break-up of her relationship with Whitehead. In the aftermath, as she started to pull her life back together, Slinger decided to recover from the experience by returning to the collages and to reconnect with Whitehead: “The fallout from the film [The Other Side of the Underneath] drove me back to Peter, but our relationship could not be repaired.”

Slinger set to work by creating a narrative and composing text to go with the images, as well as a film script. She explains she wanted to “recreate reality as a dreamscape…use this [work] to explore the psyche of the feminine inner world… to lay the inner world open.” Whitehead never made his set of the collages but kindly agreed to act out the story (though they were no longer a couple), as did Su, and, over time, the “character” shots for what would become Slinger’s An Exorcism were photographed.

The project evolved over a period of more than seven years and the result is a bewitching series of modern Surrealist collages tinged with pop culture, set to poems that are fairy tale, erotic and horror all at once. The trio act out themes that have followed Slinger throughout her life—childhood fantasy like C.S. Lewis or Alice in Wonderland, doll houses; classical mythology; supernatural horror; traditional Britishism: Pre-Raphaelites, Shakespeare, and fancy dress; influential films of the times like Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast or Barbarella; aestheticized eroticism like that of Allen Jones (a teacher at Chelsea Art School) or The Night Porter; Whitehead’s passion for falconry, and of course, a nod to the master, Max Ernst via the Bird Woman.

A pared down version of the project: ninety-nine of the collages, but not the accompanying texts, were published as a book, An Exorcism, in 1977 with a grant from Penrose’s Elephant Trust. The intention was to use the book to gain funding for a film. An extended version of the book with the text was planned with Dragon’s Dream publishing, but it was cancelled when they suffered a loss with their first book with Slinger in 1978, Mountain Ecstasy. Thousands of copies were seized and destroyed by British customs, which judged them pornographic, when they arrived from the printers in the Netherlands. Meanwhile, the filmed sequences of Lilford Hall lay in Whitehead’s archives for forty years.

Timeless and unaged, just as powerful and daring as when it was first conceived, Penny Slinger’s work of pioneering feminism, An Exorcism continues to resonate. It climbs out from the shadows in its complete incarnation to show us: “In the night sky of the opened mind there are no limitations. Doorways open up to reveal new explorations.” You’ll stagger out in delighted reverie.