Before it was a music venue, London’s Scala, on the corner of Pentonville Road in King’s Cross, was a notorious picture house with a unique progamme favouring cult arthouse, horror and queer cinema. Growing up with extended family on the nearby Caledonian Road, the area is etched into memory for the artist Louise Giovanelli, who’s repurposed the venue’s moniker for a striking new painting. “It references this idea of the theatre and what that place used to be, but also the pigment is called Scala pink,” she offers over Zoom, highlighting the components of the piece, a diptych of a pink curtain glazed to appear, additionally, purple and blue. “So it was just a nice symbiosis.”

Curtains are significant for Giovanelli. Marrying her interests in the theatrical, the Renaissance and the tactile, they have become a kind of calling card for the artist: when an earlier solo show, ‘As If, Almost’, opened at White Cube in 2022, a lime green triptych called Prairie quickly materialised all over Instagram, its bold glow enrapturing both casual fans and habitual critics. Distinctive in their size, and similarly seductive, the drape paintings seem somehow wholly contemporary while alluding to centuries prior. In ‘A Song of Ascents’, Giovanelli’s new show at The Hepworth Wakefield, Scala is among five fresh commissions to depict curtains, a group that also includes the warm red velvet number, ‘Dado’, and ‘Decades’, a sparkly blue piece inspired by Denton Working Men’s Club.

Louise Giovanelli, Prairie, 2022 © DACS, 2024 Photo © White Cube (Ollie Hammick). Courtesy of the artist and White Cube

.

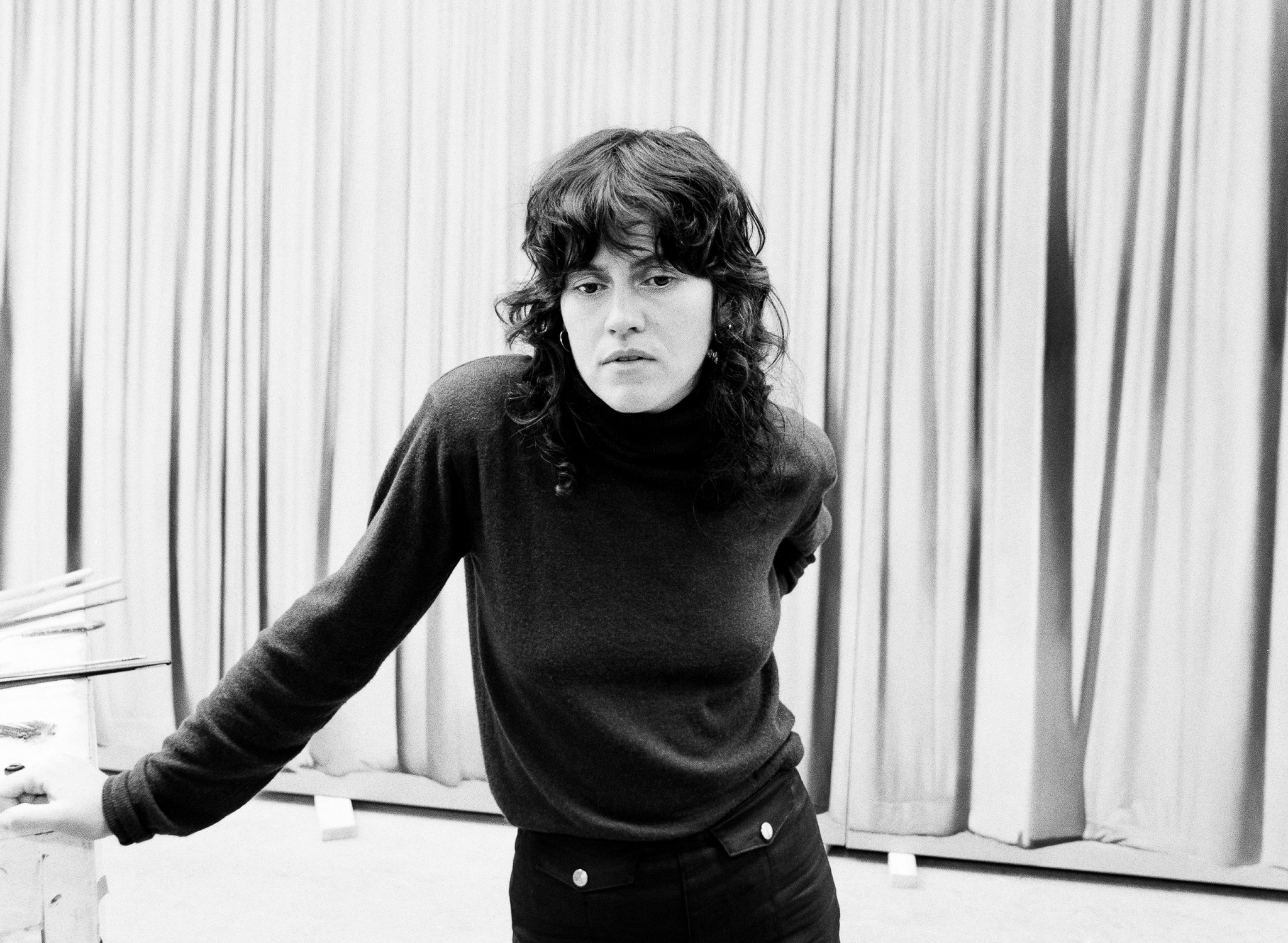

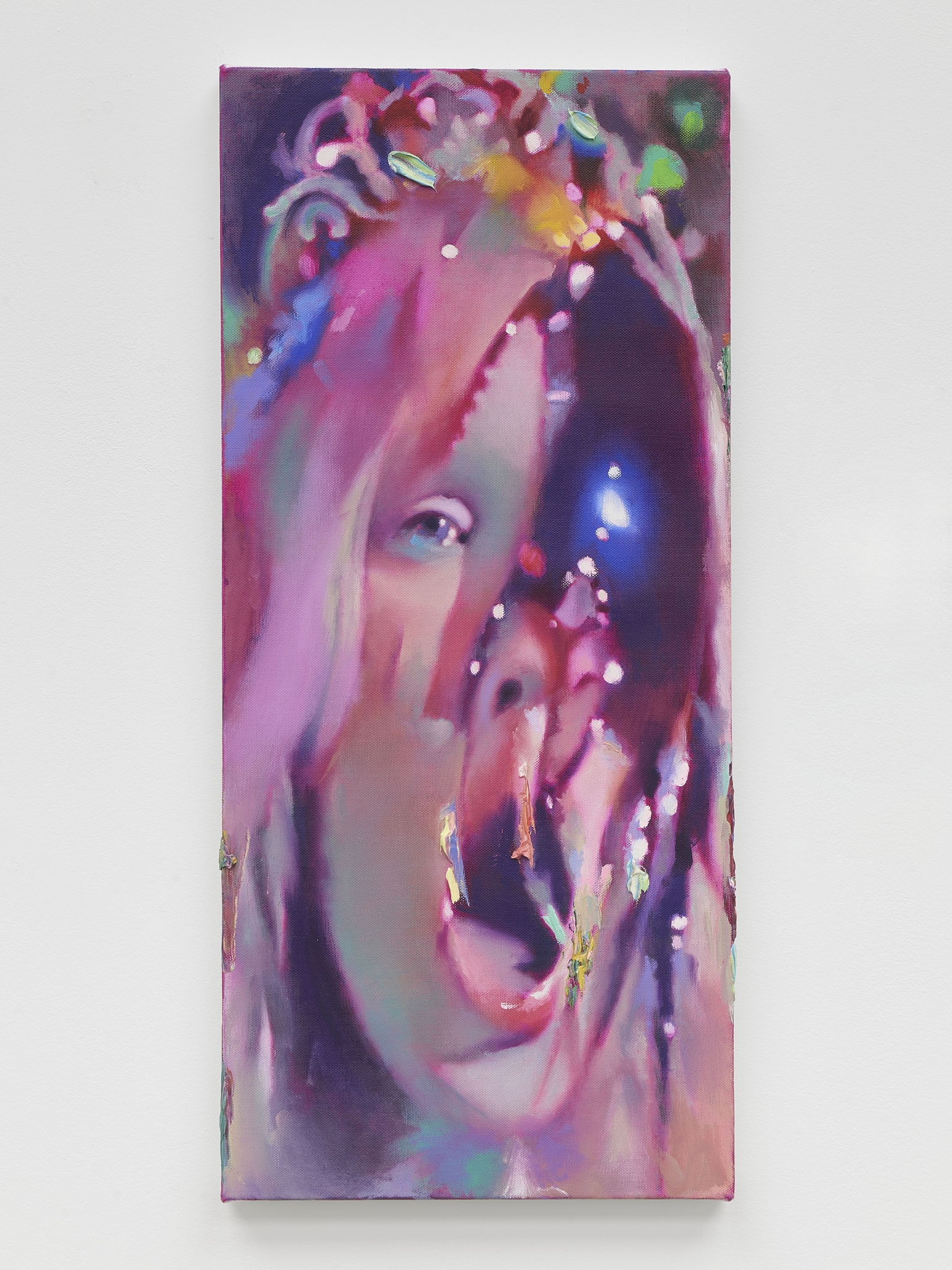

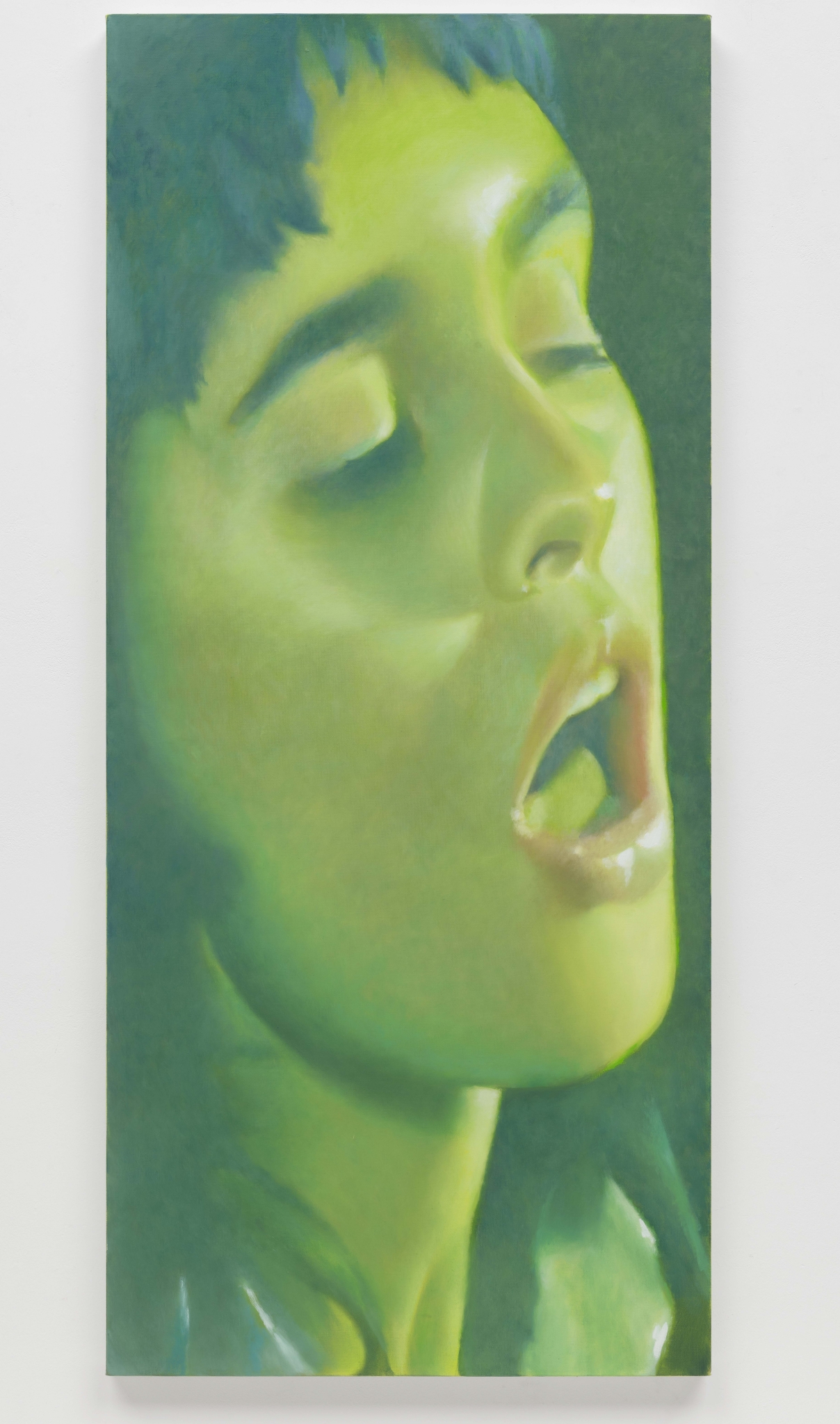

The curtains, in addition to the mechanics that renders them so curious—asking us to consider if they’re about to open or whether they’ve just been closed shut—underscore a broader preoccupation with pop culture, from which Giovanelli typically borrows and distorts, zooming in on small details like sequins and hair, or cropping and then stretching portraits (see Entheogen and Harmony, scenes from Joël Séria’s Don’t Deliver Us from Evil and Kids and Harmony Korine’s screenwriting debut, respectively). Below Giovanelli discusses her fascination with working men’s clubs, how religion has informed her work, and being a bad film watcher.

ZW: You’ve previously described how your curtains series has become an anchoring device in exhibitions. Can you expand on this, and how you first arrived at curtains?

LG: People talk about the curtains more than any other series, I think because they deal with fabric, and obviously that’s got a long art historical precedent. Curtains are seductive but also secretive; nothing is actually revealed, though there’s this sense that something will be, given we understand them as potentially opening or closing. I enjoy this tension. They’re a beautiful, seductive object, and I’m kind of playing with denying access whilst also offering, like a tantalising fragment. Then there’s the performative, theatrical element, and what that suggests. Thinking about where curtains are seen, across the whole spectrum of culture from high to low, in grand venues like theatres and cinemas, but also seedy nightclubs and working men’s clubs.

ZW: Phoebe Cripps writes beautifully on working men’s clubs in the new catalogue. How would you describe your relationship with them?

LG: I grew up in South Wales without any working men’s clubs, so I think it was probably moving to the North. They’re very interesting to me, I love the fact that a curtain and a stage in those settings grants people a bit of access to this idea of performance, whereas maybe in their everyday they’re not able to. Just seeing a curtain gives them this opportunity, for one night, to revel in a little slice of the limelight. I think some some working men’s clubs now are very aware of themselves, I prefer those that are real and just hope that people preserve them, because they’re brilliant places and offer this promise to people, which I’m fascinated by.

Curtains are seductive but also secretive; nothing is actually revealed, though there’s this sense that something will be, given we understand them as potentially opening or closing. I enjoy this tension. They’re a beautiful, seductive object, and I’m kind of playing with denying access whilst also offering, like a tantalising fragment.

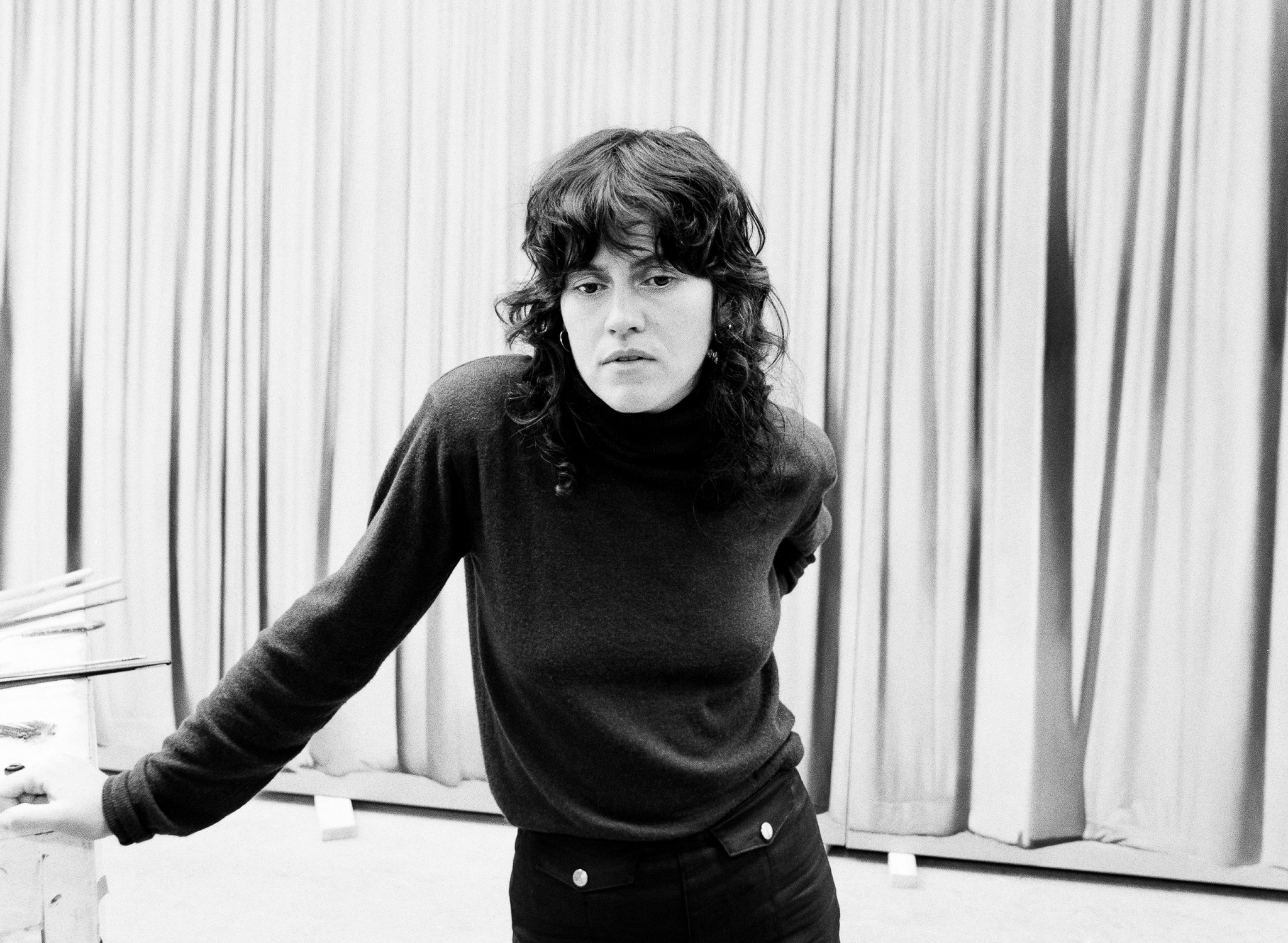

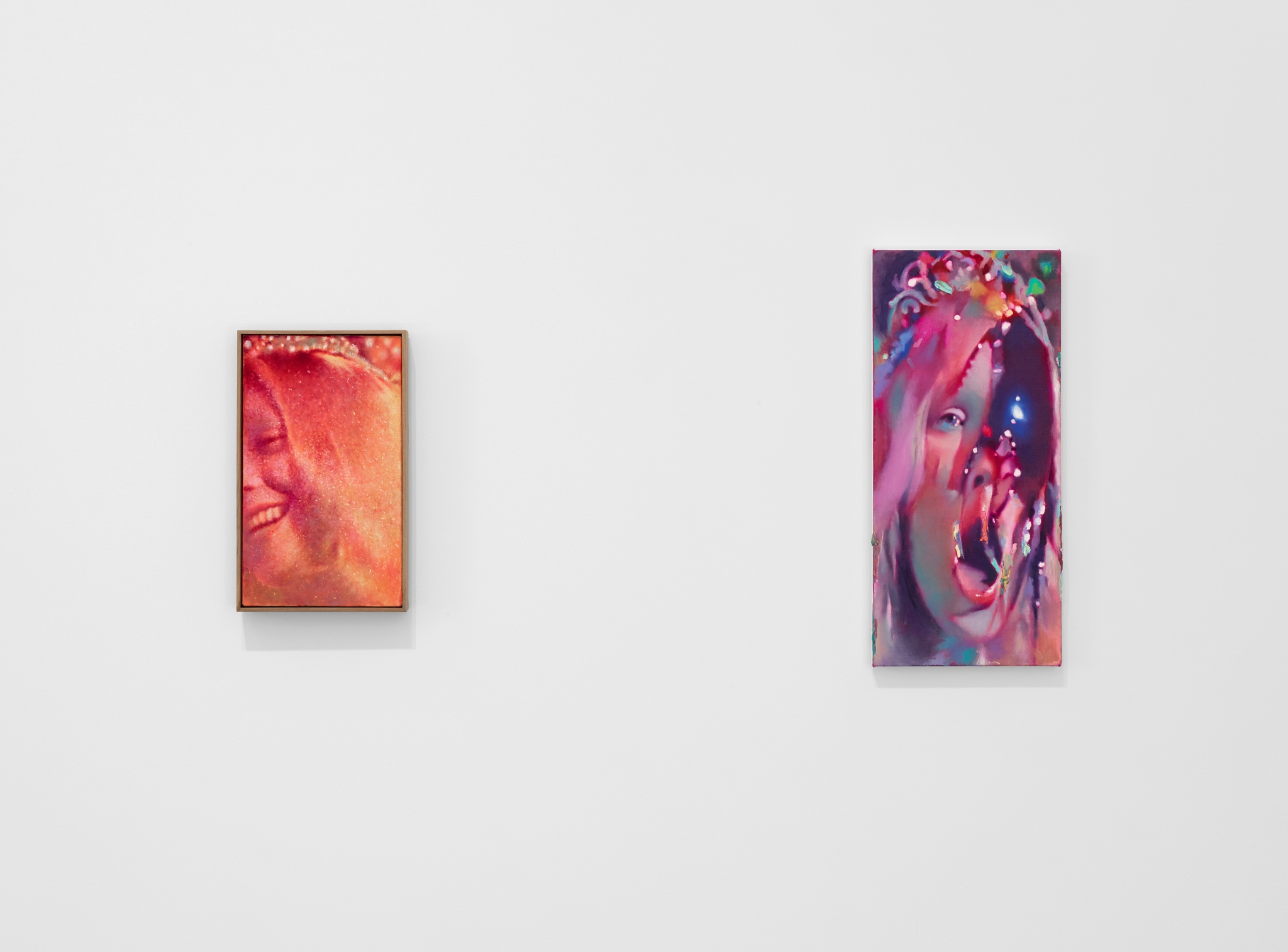

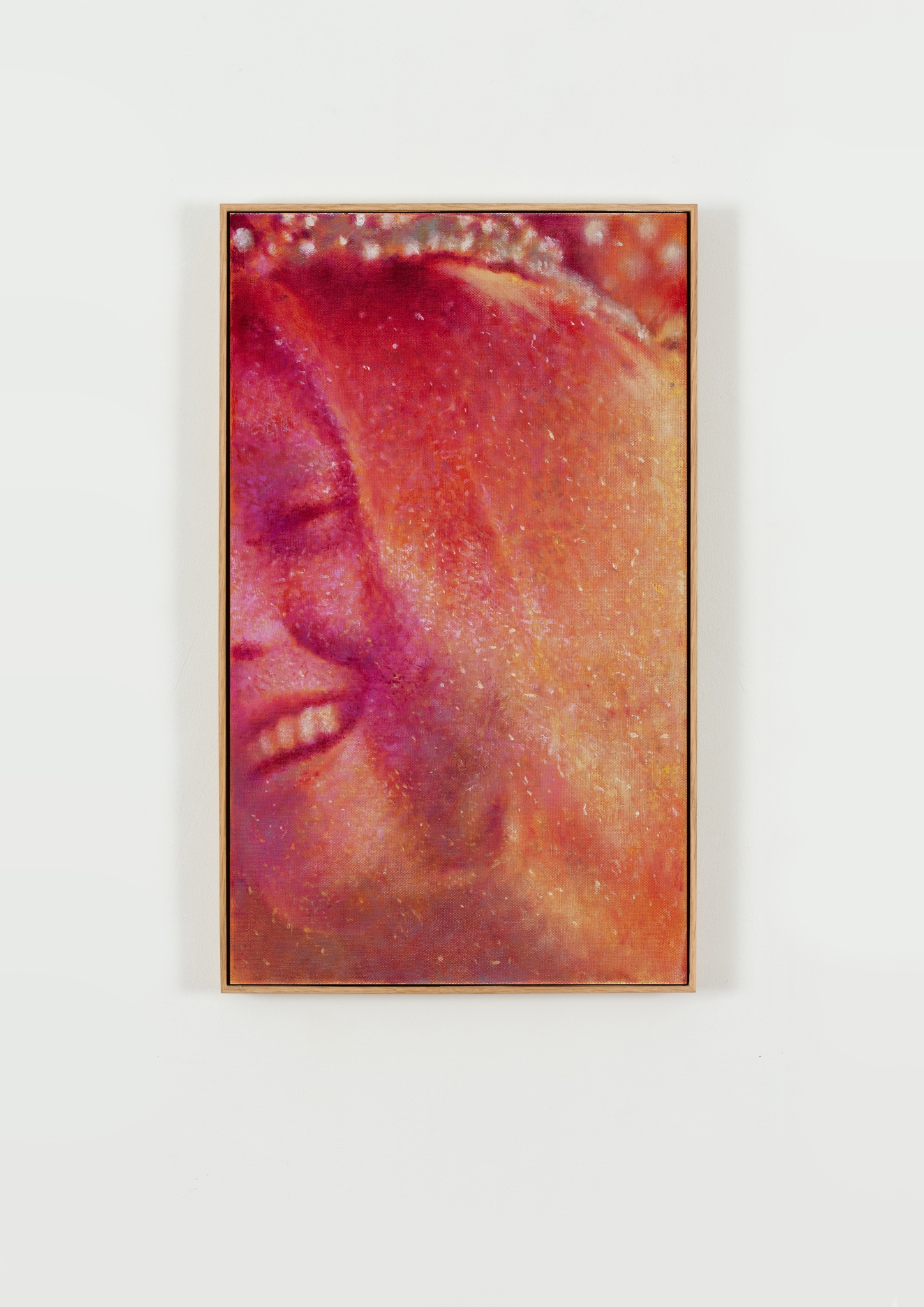

Installation view, ‘Louise Giovanelli: A Song of Ascents’ at The Hepworth Wakefield until 21 April 2025. Photo: Michael Pollard, courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield

Installation view, ‘Louise Giovanelli: A Song of Ascents’ at The Hepworth Wakefield until 21 April 2025. Photo: Michael Pollard, courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield

ZW: Elsewhere in the catalogue, in a conversation with curator Marie-Charlotte Carrier, you describe painting as research, in terms of developing ideas. What does your wider research look like?

LG: This show is really a celebration of a group of ideas I’ve been fascinated with for probably 10 years. There’s anchoring motifs, but of course new things do come into my orbit, just from encountering the world. Film, culture, television, the city I live in, traveling – the research is multifaceted, it’s something I live and think about, but it’s more of a cerebral thing.

ZW: Pop culture is an arena you draw from often, mainly focusing on the 70s, 80s and 90s. Can you see yourself integrating more contemporary references into the work, or is this distance significant?

LG: I’m also intrigued by that. The closest would be the Orbiter series, based on Mariah Carey, but it wasn’t important that it was Mariah—it could have been Shirley Bassey or Celine Dion—I was thinking more of the idea of the pop star, and you can see that (I didn’t paint her face). So it was thinking about contemporary pop icons and how they relate to historical icons in art history, trying to bridge that gap between contemporary modes of devotion to that historically. Things happening right now are too close, they need a filtering process. And I don’t think art should document what’s going on, I think art should comment on it.

ZW: You mentioned devotion. Can you speak on the role of religion and this idea of worship within your work?

LG: I was brought up Catholic, around a lot of iconography, rituals and worship; church was weekly for me. I don’t believe, but that’s not to say I don’t have deep respect for it. When I went to art school, that developed into a fascination with art history and the Western canon of iconography and the Renaissance, and I started to paint in that vein, appropriating historical imagery as a way to learn painting and to understand the ideas behind it. Paintings [still] are research; if I wasn’t painting It’d be writing a PhD on it. I’m just showing people that we all still need something higher to aspire to. It used to be church, but now it’s cinema, it’s TikTok. I’m just drawing a parallel.

ZW: This is something you highlight in your Altar series, your paintings of Sissy Spacek in Carrie.

LG: Carrie encapsulates a lot of ideas I’ve explored through separate series, all in one iconic image. I just talked about the idea of the glitz and glamour, the pop star, and that is really conveyed in Carrie with her being this prom queen: she’s on stage, there’s this theatrical element, she’s being crowned—we’re worshiping her in a sense. The whole idea of a prom queen is that, a contemporary version of going to church, crowning someone like the Madonna: it’s the same idea, augmented for our current configuration of society. What’s interesting about Carrie, and what I enjoy in my paintings, is that emotional ambiguity, the joyful, celebratory nature turning very quickly – she thinks everyone is celebrating her, then it changes radically and becomes horror, the exact opposite. How quickly that can change is something I’m really fascinated with, and I wanted those paintings to convey the subtlety between emotional states. I do that often in my female portraits, where it’s not clear what’s happening, what they’re feeling.

ZW: And cinema more generally is something you return to frequently, right?

LG: I think it’s the relationship film has to painting that I’m most interested in, I’m actually a bad film watcher, I don’t follow plot. I’m always looking at the formal aspects, so the coloration, the lighting, the psychological feeling… All the films I’ve referenced in paintings tend to be those types: quite slow moving, psychological, lots of thinking about light. Of course all those things are important elements of painting, you can’t make a painting if you don’t consider mood, tone, light and form. Ultimately, you’re trying to keep the viewer’s eye within the canvas, otherwise they move on to something else. So it’s the job of the artist to think about slow looking and contemplation, creating a zone that’s so multi-layered the viewer doesn’t want to look away. Same with film, though it’s a bit counter intuitive, because blockbusters slice through the action to keep people’s attention; I’m the complete opposite. Film is going to play a much heavier role in my next show actually, like the curtains in this Hepworth show.