A quiet icon of the Côte d’Azur, la Colombe d’Or is something of an oddity—a hotel where guests mingle with works by Calder, Chagall, Matisse and Delaunay. Constance Ayrton pays a visit.

The town of Saint-Paul de Vence is just a thirty-minute drive from Cannes, though it might as well be a century away. I arrive as the film festival down the coast wheezes toward its finale. From the taxi window, I watch the Croisette shuffle by in slow motion – film publicists, journalists and producers all dragging their fatigue like a third suitcase. As we ascend into the hills, the noise fades. The road curls toward the sky, and by the time we reach the village, the air has gone soft.

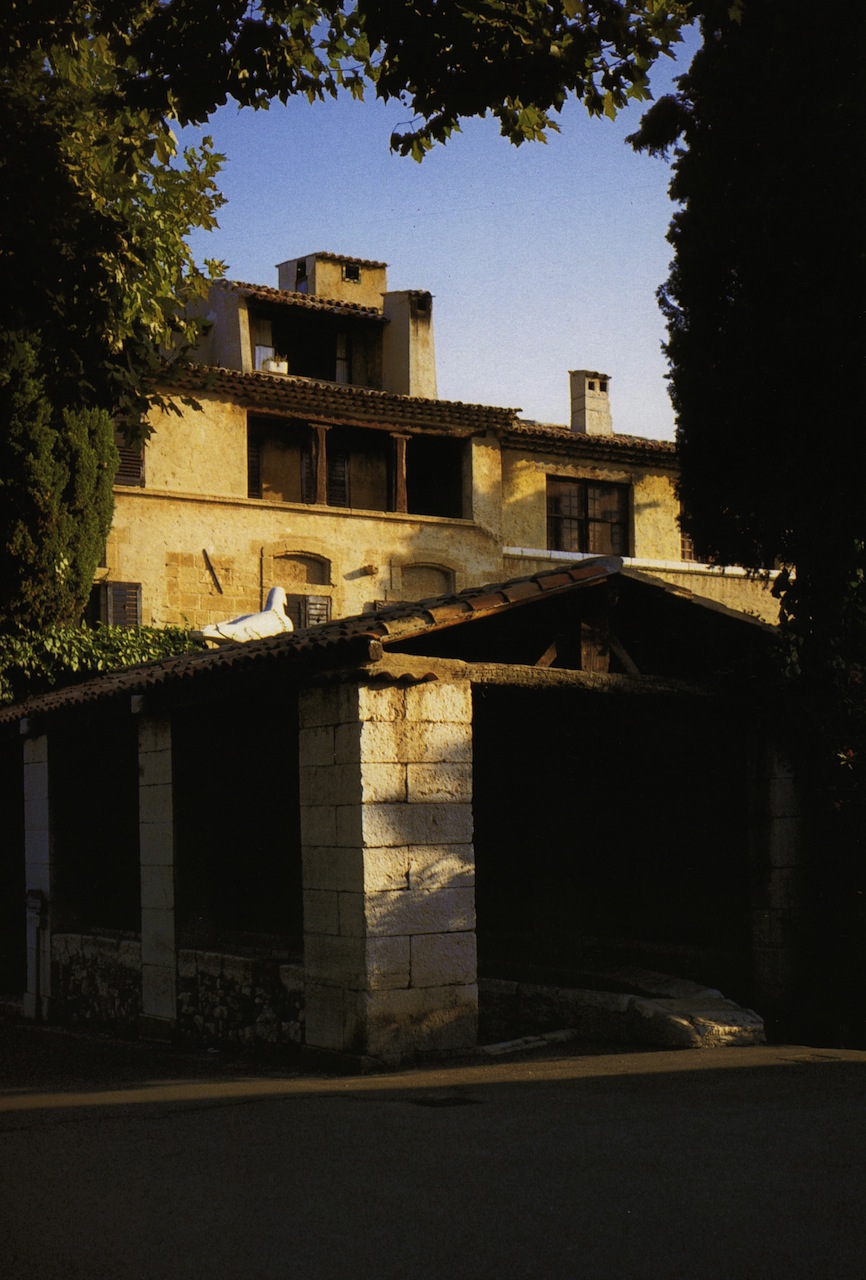

I’ve come to stay at La Colombe d’Or, the village’s main hotel, nestled between the pétanque square and the old town. Now a quietly iconic institution, it began in the 1920s, when Paul Roux and his wife, Baptistine, opened a café-restaurant that soon grew into a three-room inn. It was modest in size but magnetic in spirit. Roux, a painter himself, quickly formed friendships with local artists, offering food and lodging in exchange for their work. Dufy, Signac, and Soutine were among the first. Before long, La Colombe had transformed from a humble inn into a gathering place for painters drawn to the light and magic of Provence. Roux even put up a sign that read: “Ici, on loge à cheval, à pied ou en peinture!” — “Lodgings for man, horse, or painter!”

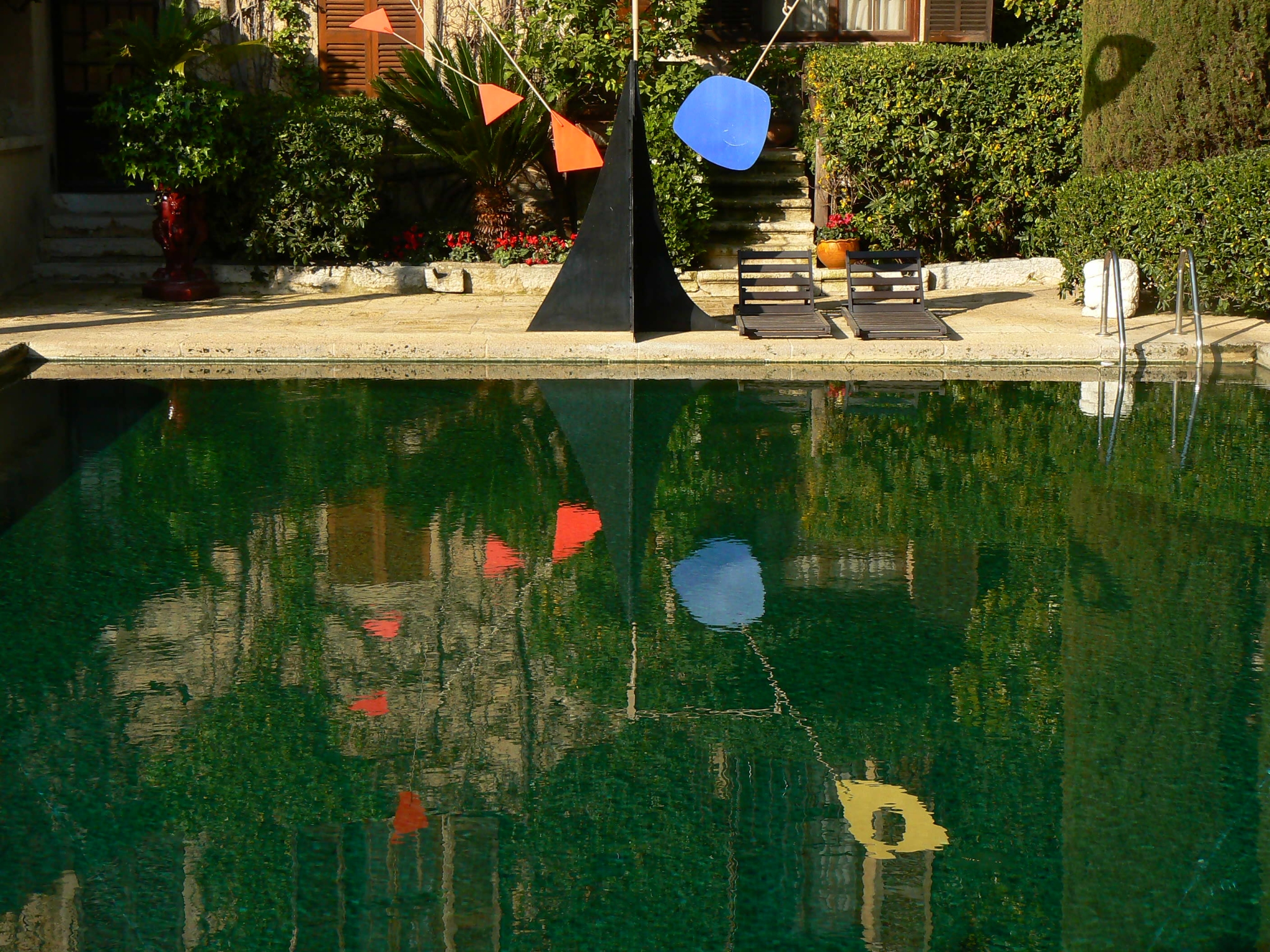

Stepping into La Colombe d’Or is like stepping into a museum—but not the clinical, white cube kind. It’s an intimate, sun-drenched space where you might easily decide to eat, nap, or stay forever. Just inside the entrance, to the left, stands a gigantic marble thumb, César Baldaccini’s Le Pouce, dated 1983. It greets you like a surrealist handshake. I pass through the courtyard, where guests are lunching on grilled fish and sipping the house rosé. Turning right, I come across a mosaic by Fernand Léger, created especially for the hotel. Its colours seem to borrow directly from the courtyard: dappled greens, soft golds, stone whites. The light filtering through the trees casts patches of shade across it, like paintbrush strokes left to dry.

I make my way to the lobby. The cream-coloured hall where guests check in is lined with old paintings: Provençal landscapes, still lifes, and a poised pair of portraits by society painter Clémentine-Hélène Dufau. A vine-leaf fresco, faded with time, winds around the frames. I feel far from the Riviera of my childhood. Summers with my Niçoise grandmother were all bustle and brightness: morning markets stretching into the streets, walks along the crowded Baie des Anges, warm socca eaten from paper cones. Nice buzzes with a sharp, salty energy. But here, everything bears a gentle erosion.

I’m shown to my room, where a small shuttered window looks down on the courtyard. On the walls: a Matisse, a Dufy. And above the bed, a Picasso. Naturally. It’s a work on paper from 1961, showing a loose, clownish figure rendered in a few confident lines. It stares back at me, bemused, as if to ask what I’m doing in its room.

With all this history in mind, I stroll the corridors, half-expecting to hear Arletty’s ghostly laugh echoing off the stone. On the second day, I tear myself away—reluctantly—to explore the town. St. Paul de Vence is a cultural haven in its own right. The cobbled main street is flanked by galleries that spill onto the pavement—local sculptures, ceramics, delicate works on paper, oversized canvases fit for statement walls, and, here and there, a Chagall. At the summit of a fifteen-minute climb sits the famous Fondation Maeght, where a silent army of Giacomettis stands in watchful formation. On my way back, I pause at the Chapel Folon, a quiet sanctuary decorated by Belgian artist Jean-Michel Folon. The interior shimmers with mosaic from floor to ceiling, glinting in warm Provençal hues.

That evening, on my way to dinner, I linger once more in the dining room for a closer look. A Léger, dedicated to Roux, a Braque, a Delaunay—each artwork arranged with unstudied elegance, like family portraits. Some are half-hidden behind the generous sprawl of potted plants, casually tucked into view. The light is hazy and amber-toned, casting a soft golden wash over the worn wooden tables. A few of Paul Roux’s own paintings are here too, at ease amongst 20th-century masterpieces.

Once you’re in, what holds you isn’t so much the art or the service—though both are impeccable—but the atmosphere. It’s a sense of continuity, of something gently held in time. The hotel still glows with the spirit of its earliest years, when artists paid in canvases and conversation.

Constance Ayrton

I bump into Madame Roux, gliding through the house. Keeper of keys and stories, she speaks of La Colombe as if it were a well-guarded secret, a hidden garden, she says, and she prefers it that way. The hotel doesn’t so much advertise as it lets itself be found, drawing people not through algorithms or splashy campaigns, but through the quiet pull of loyalty. The website is little more than a nod: a phone number, an email address, a few softly blurred photographs. No booking engine. You either know, or you don’t.

Once you’re in, what holds you isn’t so much the art or the service—though both are impeccable—but the atmosphere. It’s a sense of continuity, of something gently held in time. The hotel still glows with the spirit of its earliest years, when artists paid in canvases and conversation. To this day, contemporary artists find themselves drawn in. Works by Jean-Charles Blais hang alongside Delaunay and Matisse. A recent ceramic piece by Irish artist Sean Scully now sits by the pool. Today’s habitués bring tomorrow’s. The conversation continues, one artwork at a time.

On my last morning, I take one final steam in the tiny spa cabin tucked behind the garden. In the dim room, I half-expect a Matisse to emerge—some forgotten canvas, edges curling. As I pack, I glance once more at the Picasso above the bed. Like Clouzot, I catch myself fantasising about building a modest shed out back in exchange for a few still lifes and some good conversation.

It’s hard to leave a place where you can nurse a quiet drink in the same bar where Marlene Dietrich once flirted with Jean Gabin. As the French writer Colette once wrote in the guestbook Wait for me, Colombe, I’m coming back. I will be too, I hope.