Known for her rhythmic abstractions in pastel coloured hues of translucent paint washes, Helen Frankenthaler’s mark on art rivals that of contemporaries such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. Lydia R. Figes explores the life and work of the American painter, whose brought a sensual and feminine note to Abstract Expressionism.

“There are no rules. That is how art is born, how breakthroughs happen” the artist Helen Frankenthaler once remarked. “Go against the rules or ignore the rules.” Encapsulating her non-conformist spirit, the show Helen Frankenthaler: Painting without Rules at the Guggenheim Bilbao crystallizes the life and work of the inimitable painter, who rose to prominence as a key figure in Abstract Expressionism and Manhattan’s downtown, bohemian scene between the 1940s and 1960s.

Having previously debuted at Florence’s Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi and curated by the Director of the artist’s catalogue raisonné, Douglas Dreishpoon, this iteration of the exhibition allows its monumental works to breathe and spark dialogue with one another in the vast, open plan space of the Guggenheim. Revealing the artist’s protean handling of paint, we can clearly discern Frankenthaler’s ambitious and insatiable quest for artistic freedom, underpinning her lifelong mantra: no limitations, no rules.

Known for her lyrical abstractions in pastel coloured hues of translucent paint washes, Frankenthaler developed her own approach to abstract painting: the soak stain technique. Born in 1928, she emerged on the post-war art scene having grown up in cosmopolitan affluence. Raised on the Upper East side, a few blocks away from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, she was the third daughter of a respected New York state Supreme Court Judge (who died when she was 11 years old). Frankenthaler’s precocious flair for art led her to the Dalton School under the instruction of the Mexican modernist Rufino Tamayo, before later enrolling at Bennington College, where she was taught by Paul Feeley. Undoubtedly, her privilege set her on the right path to success. As Mary Gabriel, author of Ninth Street Women (2018) emphasises, Frankenthaler’s innate confidence in her talents propelled her forwards: “I was a special child and felt myself to be” she once admitted.

Expressing herself through art was inseparable to Frankenthaler’s sense of being. According to Dreishpoon, if she hadn’t committed to painting, she would have become a writer—a mode of expression that ran parallel to her life as a painter. To satiate her intellectual curiosity, Frankenthaler surrounded herself with the artists and thinkers of her day, notably, the writer Frank O’Hara, sculptors Anne Truitt and Anthony Caro, writer Clement Greenberg, and artists Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and David Smith amongst many others who shaped the avant garde community of post-war America.

Frankenthaler’s integration into this scene began in 1950, when she had the chutzpah to introduce herself to Clement Greenberg. Then in his forties, and well established as the critical voice on modern painting in America who wrote for The Nation and Parisian Review, Frankenthaler (who was only 22 years old) was unperturbed by his reputational magnitude. She called him up and invited him to her Bennington College degree show. Charmed by her audaciousness, the critic agreed on the promise that “drinks would be served” (she swiftly assured him that both martinis and manhattans would be offered). Greenberg kept his word and turned up, though according to author Mary Gabriel he clumsily insulted her Cubist-inspired work Woman on a Horse. However, Frankenthaler wasn’t deterred by the criticism (another reflection of her unassailable confidence). On the contrary, the critic and artist hit it off. A romantic and intellectual relationship ensued for the next five years.

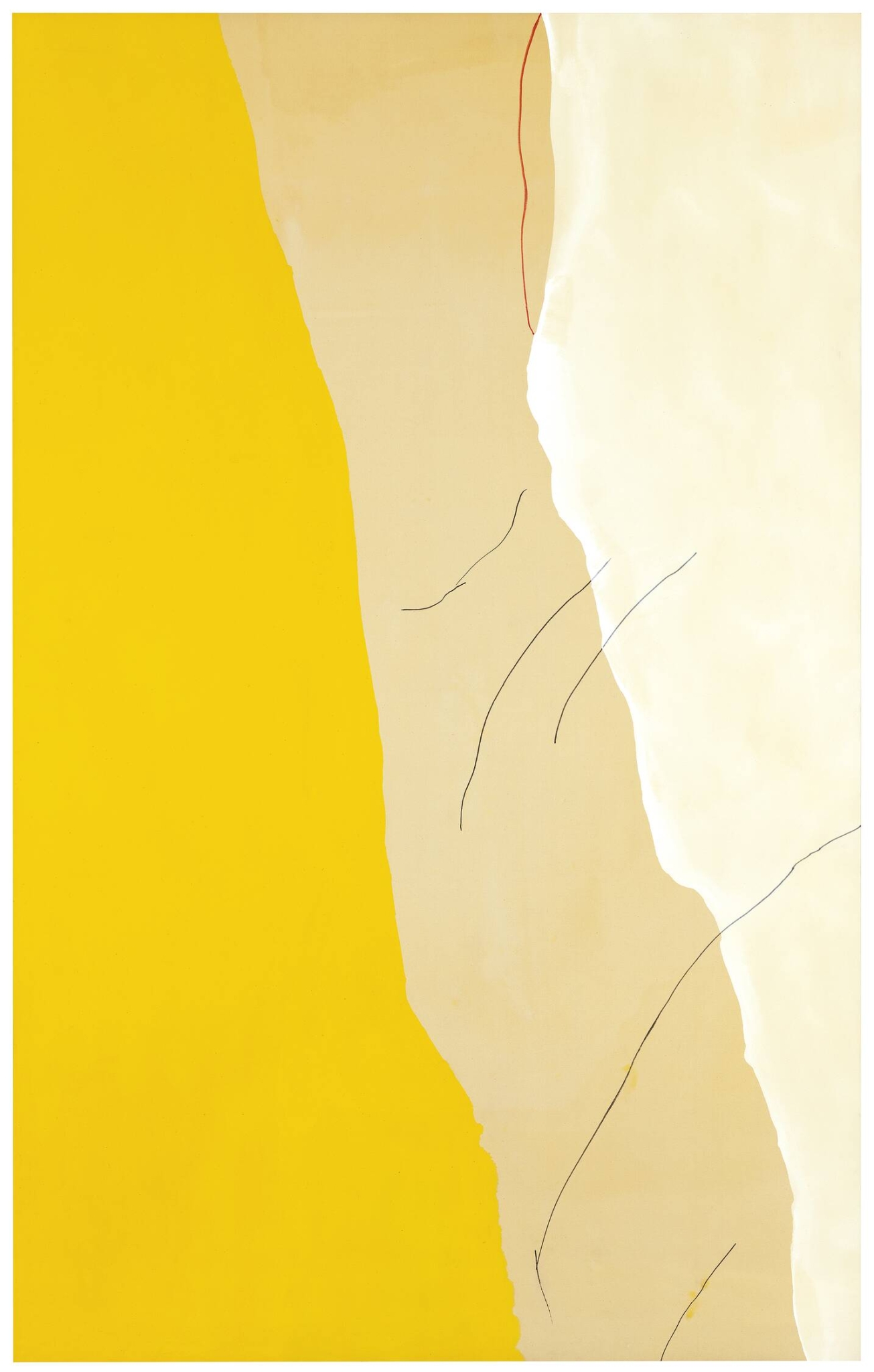

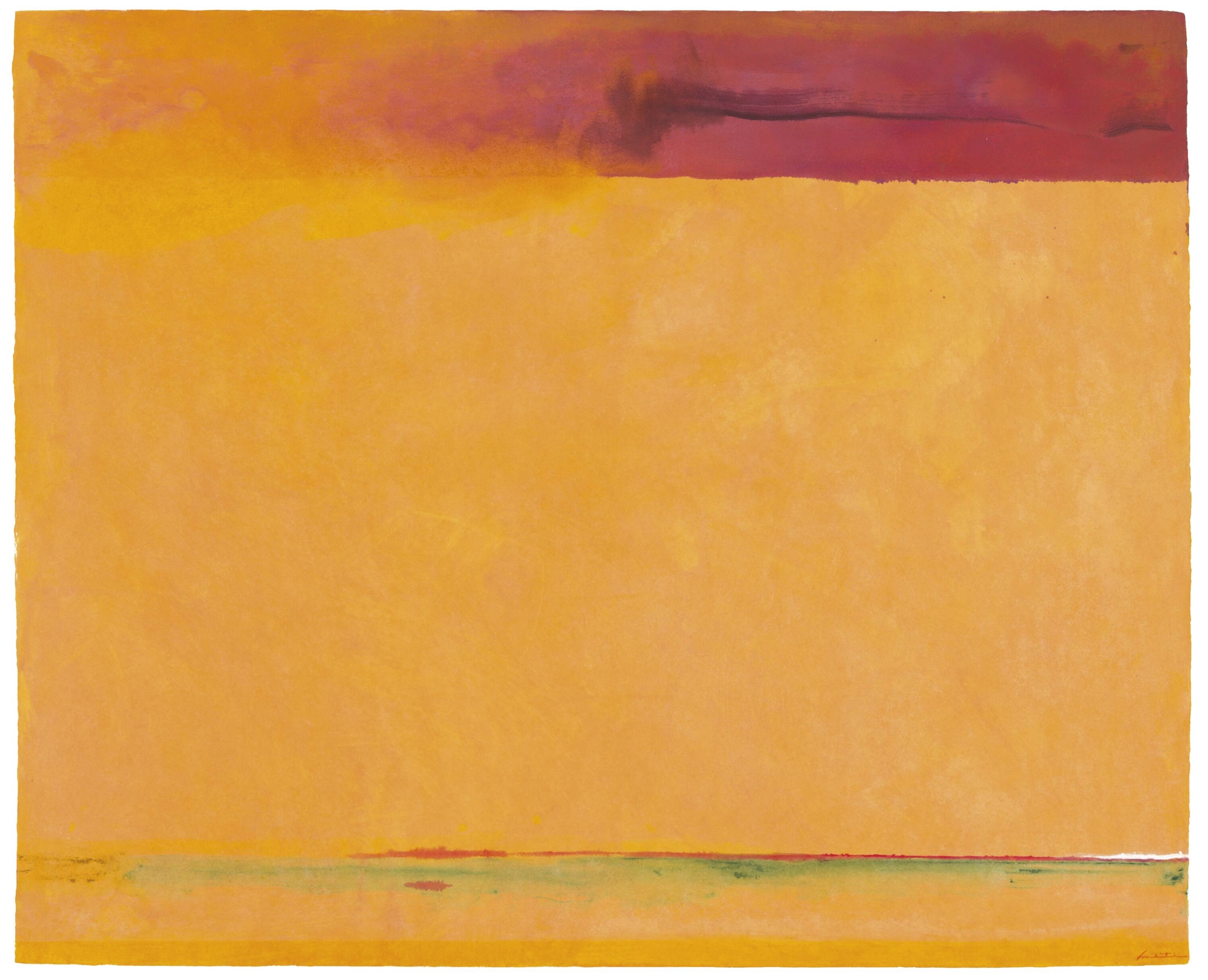

Beyond her relationship with Greenberg, at the crux of Painting without Rules is the desire to capture the myriad relationships, friendships and synergies surrounding Frankenthaler. In particular, it positions her work next to paintings by Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, indicating that the former and latter were pivotal in shaping Frankenthaler’s artistic trajectory. Describing her first encounter with Pollock’s work as a “beautiful trauma”, his risk-taking approach to painting—embracing visual chaos and unpredictability—greatly inspired Frankenthaler. Yet while she drew inspiration from Pollock’s frenetic drip paintings in the early 1950s, by the following decade, she had turned her attention to the sombre abstractions of Rothko. This stylistic shift is detectible in her abstractions across the decades, particularly following her summers spent in Europe and Provincetown, Cape Cod, when the artist absorbed the atmosphere of the seaside and coastal landscapes she found herself immersed in. A sense of boundless space, of sky, sea and clouds, is captured in works such as Santorini (1965) and Ocean Drive West #1 (1974).

Frankenthaler embraced being a woman, though she didn’t want to be reductively labelled as one. “I don’t resent being a female painter” she once insisted. “I don’t exploit it. I paint.”

Reluctant to be described as a ‘woman artist’ or a feminist, Frankenthaler nevertheless affiliated with the women of Abstract Expressionism, in particular Grace Hartigan, Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning and Joan Mitchell (although such relationships are somewhat downplayed in the Guggenheim show). Unlike the majority of her female peers, Frankenthaler received great recognition in her lifetime, evidenced by the famous photoshoot with Gordon Parks for Life Magazine in 1956, and the fact that she exhibited in major institutional shows, such as her solo show at The Jewish Museum in 1960, and her representation for the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1966.

Why, in comparison to her female contemporaries, did Frankenthaler’s artistic reputation skyrocket so impressively in her lifetime? Although the sceptics and detractors have pointed to her close ties with influential men (her relationship with Greenberg, and later the painter Robert Motherwell whom she married in 1958), as the Guggenheim exhibition attests, her authentic and fresh style was the principal cause of her ascendence. While Frankenthaler admitted to taking inspiration from her male peers—Pollock, de Kooning and Rothko as well as Picasso, Braque and the Old Masters—she never shied away from embracing the sensual and soft qualities that have come to define her unique work, such as her breakout painting Mountains and Sea (1952). Frankenthaler embraced being a woman, though she didn’t want to be reductively labelled as one. “I don’t resent being a female painter” she once insisted. “I don’t exploit it. I paint.”

Other key works featured in the show, Open Wall (1953), Alessio (1960) and Moveable Blue (1973), accentuate the brilliance of her soak stain technique. The process involved thinning down paint with turpentine or kerosene to create a fluid wash, which she would then proceed to pour all over her unprimed canvases. Inspired by Pollock, she similarly placed the linen canvases on the floor, allowing her to move freely across its surface. She would then withdraw, standing back to observe how the paint seeped into the surface. When it was adequately stained, she would sponge, wipe and drag the colours in different directions, occasionally intervening with her hands and thumbs. As seen in the surface of Alassio—a vibrant canvas in Mediterranean colours, named after the Italian coastal town she visited with Motherwell in the summer of 1960 – a smudge of deep crimson (no doubt applied with a thumb) brings a sense of aliveness to the surface.

In many ways, Frankenthaler was a choreographer as much as a painter. Her monumental abstractions reflect her physical embeddedness within the works, as she shifted, glided and danced around her earthbound canvases. Following her intuition, she engaged in an intimate dialogue with her paintings; a collaborative waltz between paint and canvas. Like a dancing companion, she allowed them to guide the process. “Every picture tells you what to do,” she once said, “that’s the glory of it.”

Helen Frankenthaler: Painting Without Rules in on at Guggenheim Bilbao, Spain until 28th September 2025.