There aren’t many in the art world operating quite like Esben Weile Kjær. A rising star, the Danish artist’s work demonstrates a flair for pop, re-appropriation, and nostalgia. Though the millennial artist lives in Denmark, his practice is heavily informed by “The American Dream” and the aesthetics of the entertainment industry, with his performances, installations, and stained-glass work examining his generation’s construction of selfhood, and the rise of popular culture in determining one’s experience of authenticity.

Lucca Hue-Williams talks to the Danish artist about his upcoming performance at Museum der Moderne Salzburg in July.

Lucca Hue-Williams: Can you tell me about how your performance, sculpture and stained glass work is connected?

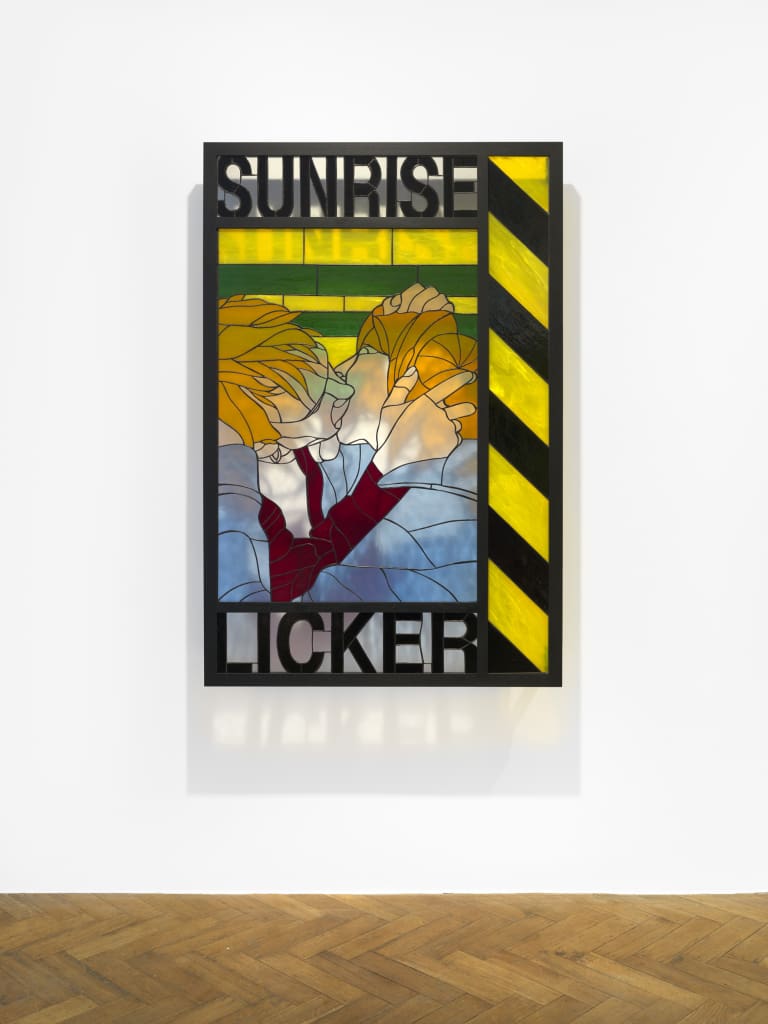

Esben Weile Kjær: All my work is connected and derives from the same place: there is no hierarchy. However, the sculptures are often part of the performances which are presented as spectacles or events. I have always been inspired by places of community that have these windows, such as medieval churches, casinos and old Parisian absinthe baroque bars. To start, I wanted to make my own place, the idea is not fully formed yet but the windows are an important aspect to that.

LHW: How do the notions of liquid surveillance and the ‘Omniopticon’ relate to your practice?

EWK: There is a paradox in my practice in relation to liquid surveillance. I grew up on the internet as part of the first generation with Tumblr, which was the first form of visual social media we used to create our own virtual identity. Now, as a millennial, I am using all sorts of platforms to create identity and share images. There is a sort of alienation that comes with it. My work explores the power dynamics and performativity of the digital world, but I also have a real fascination with the analog. I’m really interested in the idea of retro-mania and in using nostalgia as a strategy. In a society that is so hyper digital, the analog becomes almost a fetish.

Growing up, I was very active in the left wing, anarchist and anti-fascist movements in Copenhagen. I think I was 14 or 15 years old. I joined the movement at a time when the way these communities communicated was shifting from the analog to digital. For instance, to communicate an idea or a demonstration for these subcultures, we printed fliers and posters – physically hanging them in the city or interacting with others to spread the word. Myspace completely changed this and gave the potential to communicate to a much bigger audience. Suddenly, these subcultures, including street parties, and raves, became popular culture. Even if only a small group of people were participating in the countercultural events, it could be communicated to the masses. I found the energy and escalation, and the role of these new communication channels particularly inspiring. All of a sudden you could appropriate different texts and visual languages and be really performative for an audience much bigger than you were used to.

LHW: That’s interesting.

EWK: In Copenhagen, I used to visit a place called the Old Youth House, which was home to many sub-culture groups. It was built by the working class of Nørrebro, which is very near to my studio. Before it was evicted by the police, it would host really important events and movements such as the Women’s International Day led by Rosa Luxembourg. The walls were covered with paintings commemorating these histories of the House. It was both romantic and nostalgic because it created a history for this community that we could all tap into as part of our identity. So even though it’s not my history, because for instance, I was not alive at the same time as Rosa Luxembourg, the Women’s International Day movement became part of my history. There is something about this collective history that we could all access that felt democratic and inspiring.

LHW: You speak frequently about the idea of the spectacle and performativity, which is prolific in American popular culture and seamlessly integrated into your practice.

EWK: I have always been fascinated by pop culture and have this punk approach to the way I work. I believe that historically, youth movements change our collective narrative of popular culture. There is a potential of pop that fascinates me—that subcultural ideas can suddenly reach a larger audience through pop culture. And it’s often pop culture icons that make an idea much more radical than in many of the original movements. Like when Beyoncè became a feminist. I also think social media has completely changed the hierarchy of who is communicating radical opinions and how they are shaping the world. This is the case not only with gender or race related issues, but also with climate. Greta Thunberg has also become a pop cultural icon, right? If you present something radical or unconventional, a new kind of aesthetic, you can make a giant impact. Employing pop culture imagery and strategy is a very effective tool in my practice.

Also, so much of the West and Europe is shaped by America. Even though New York right now feels like a museum—it’s kind of dead. When I walk around the city, everything feels like a film set because so many movies are set here. American pop culture is both lapsed in a way but also prolific. In Northern Europe, we are still so fascinated by it, and it informs everything. Everything is somehow connected to the States. The idea of the ‘American Dream’ has evolved but it still exists as fiction. It exists in television, in Netflix, and is of course not ‘real life’. However, what is not real life is still real, and I guess that is the consequence of social media.

LHW: Your practice is evidently informed by these ideas of the ‘American Dream’ and consumerism. It reflects both your fascination and skepticism, which is obviously a key element of pop art. How did this come about, given your childhood in Denmark?

EWK: There is a utopian aspect of my work that is always right under the glossy surface. This really comes from growing up in such a small country in the 90s when consumer culture was at its peak. Everything was a mass produced, plastic object and every month there was a new thing that you had to buy. It was never produced in Denmark, right? It was designed in America and it was produced in China. It was that naïve era of consumerism, when there was no war, no climate crisis that we knew of yet. Then growing up to see the very real consequences of that, suddenly the realism of being confronted with all these issues, creates this dystopian feeling or melancholy connected to these objects when we now look at them. That’s why I also find it interesting to create them in different materials. For example, the JoJos, my marble sculptures, were the biggest toy trend in Denmark when I was a child. They were currency in the schoolyard that you would exchange with other students. However, they’ve disappeared out of society because the trend evolves into something else. Looking at it now, everyone in Denmark has a nostalgia connected to these small plastic objects which become symbols of the old world. I insist on recreating them in marble, which symbolizes how their meaning has shifted. This is why I am really interested in when objects and symbols shift meaning and how we connect with them. That’s the same with my magic wand sculpture which I created in bronze.

LHW: In what way do the Magic Wand works present popular culture as an evolved experience of your childhood?

EWK: These wands are both fantastic and tragic. I just remember them so clearly: buying them in these cheap toy stores, putting in their batteries, pressing a button that made them blink. They would maybe even make a sound and if you were lucky, they would work for maybe two weeks. And it felt so magical. You felt as though this object could hold all your fantasies and desires in the world. It became the object that could be everything, right? If you have a magic wand you can do whatever you want. Everything becomes possible and there are endless opportunities. You believe in your wildest dreams, but then they break, you know? So that whole narrative is so short and so fragile. I think it’s interesting to transform the idea of fantasy or imagination into a monument. Which is why I chose to cast the fragile, plastic wand in bronze and create the star in glass – it becomes something that will exist in 200 years, and will patina beautifully. I feel this aspect of my sculptures both disgusts and fascinates people. For example, the Butterfly sculpture went completely viral. People were really confronted by it and many people on Instagram went crazy and found it so scary.

LHW: Why is the medium of stained glass so fundamental to your practice?

EWK: The process of creating stained glass is an analog way of producing life through an image. With all the time our generation spends on screens, we think only about putting life through images that we want to exist. Stained glass is also a limiting medium, there is only a certain level of detail you can get into the image. Everything appears cartoonish, which resonates with a broader audience. In the beginning, I used more historical images, but now I use references of my own work, and re-appropriate photos of my performances in stained glass format. The graphics for these more recent works were inspired by the history of posters and flyers for demonstrations, parties, and propaganda. When I translate these graphic motifs taken from ephemeral posters into lasting stained glass, it transforms in the same uncanny way as does casting a plastic toy in bronze.

LHW: Your work reappropriates and self-references images from your previous performances. Considering your involvement with sub-cultural groups in Copenhagen, do you think the notion of the iconic image in media plays an important role in your work?

EWK: All popular culture consists of images which are redistributed many times, but there is something about employing strategy and playing around with them that interests me. I see it as a performative gesture. If you look at a politician communicating in an election, it’s serious, but at the same time, the strategies employed are primitive. Images and slogans are distributed in a way that is easy to say and reproduce. They are trying to create an icon, and there is something very simple in these processes. In my practice, it’s really fun to try and create a simple visual language, not to control the outcome, but to understand these performative strategies. What is this aesthetic world we are navigating? That’s what I’m trying to understand. I’m not trying to make the images a success, but I’m trying to use these performative strategies in the process.

LHW: Do you believe there is such a thing as originality?

EWK: I don’t believe in originality at all, but I am really fascinated about how society is obsessed with the idea of originality and also how that has created the idea of ‘the genius’ and ‘the authentic’, and how problematic these archetypes are in our society. I think that is the core of my practice – that I’m not interested in trying to create something original. I’m trying to understand and grasp the complex world of images that we’re living in every day. And that is what I do. I have a really big distance to this idea of originality. I don’t believe a good image is an original image. Everything is a reaction of something else and I think that’s really beautiful.