Lucy Davies considers the course of Paul Cézanne’s life against the seasons of Montagne Sainte-Victoire, a source of native pride and endless inspiration for the visionary painter.

Think modern art, and almost certainly the south of France comes to mind. We know its pulsing blue skies, glittering sea, cypress trees, and limestone plains better than almost any other landscape in art history.

Artists from Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso to Raoul Dufy and Vincent van Gogh were enraptured by the region, but arguably none more so than Paul Cézanne, who was born in Aix-en-Provence in 1839 and rarely strayed long from that area all his life.

The idiosyncratic language he invented to describe its rugged green and gold terrain—and particularly the craggy hump of the Sainte-Victoire mountain that presides over it—was unlike anything the art world had seen before and the reason Picasso referred to him as “the father of us all”.

We might say Sainte-Victoire was in Cézanne’s blood. He grew up in its shadow, after all, and with his childhood friends—the future novelist Émile Zola and the eminent geologist and paleontologist Antoine-Fortuné Marion—spent many hours exploring its pitted foothills and wooded trails.

Cézanne shared Marion’s passion for geology, a science that transitioned in the early 19th century from being part of broader natural history to an independent discipline, and which, in a part of France strewn with prehistoric monoliths and megalithic structures, was easy to indulge.

1 Drawings of fossils and strata in some of Cézanne’s early sketchbooks.

There are even drawings by Marion of fossils and strata in some of Cézanne’s early sketchbooks 1, and the artist’s rich knowledge of geology would later underlie the way he strove to convey landscape’s fundamental forms and its silent timelessness. “In order to paint a landscape well, I first need to discover its geological foundations,” he said.

Montagne Sainte-Victoire first makes an appearance in Cézanne’s work in the 1870s, though as a background rather than principal subject. It’s there in The Railway Cutting (1870), for instance, and Bathers at Rest (c. 1876-77). Cézanne had moved to Paris by then, where he enrolled at the Académie de Charles Suisse (a popular and informal art school), spent hours in the Louvre (it prepared him “to see well the following day”, he said) and fell in with the impressionists at their favourite haunt in Montmartre, the Café Guerbois. Camille Pissarro became a particular friend. The pair often went painting together in rural Pontoise and Auvers, north-west of the city, where Cézanne learned his preference for painting en plein air.

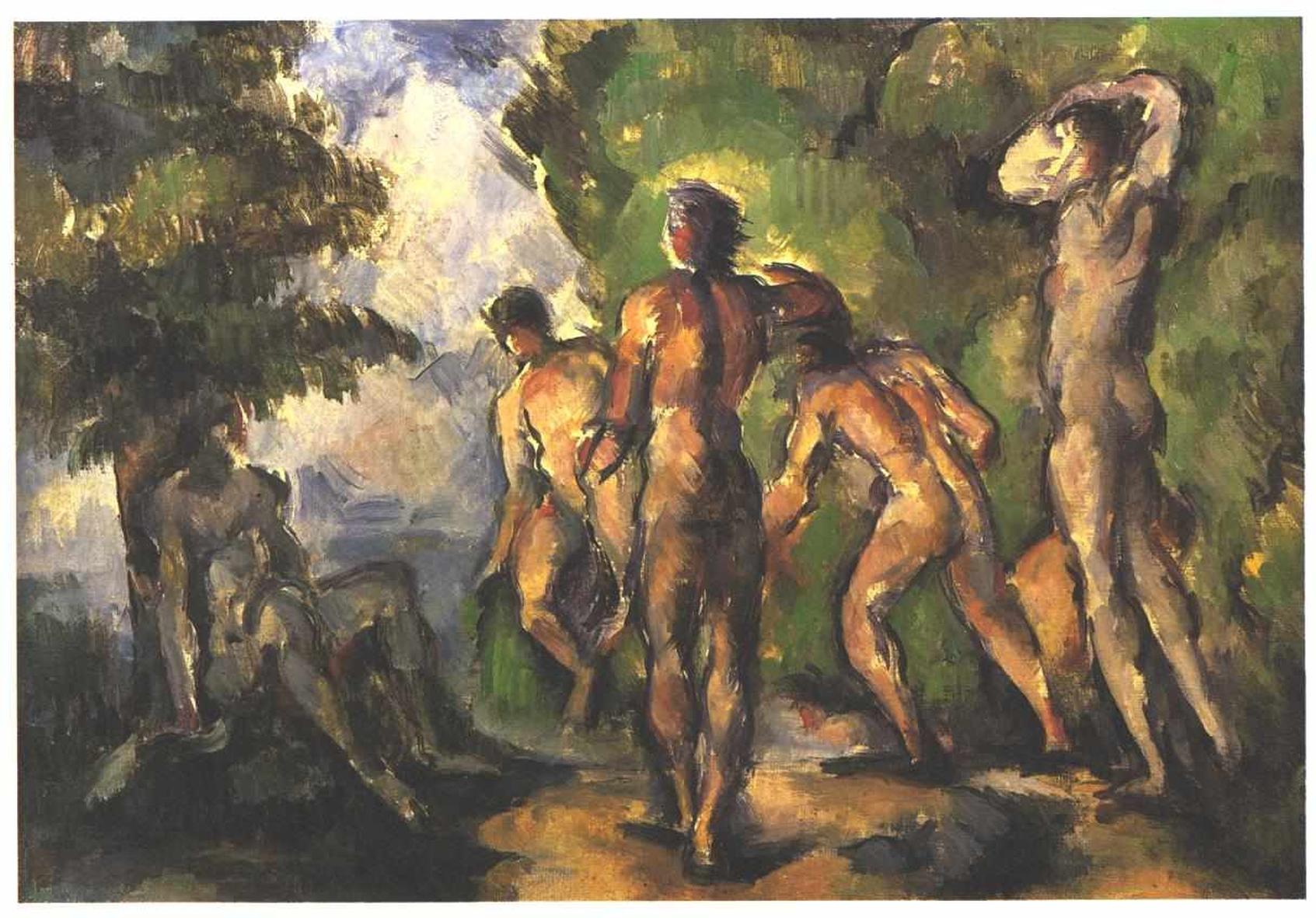

He also acquired the Impressionists’ technique of using short, distinct brushstrokes, and took part in some of their group exhibitions (in 1874, 1876, and 1877), though he never quite fell for the fleet effects of light and atmosphere that were Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, and co’s sine qua non. Instead, he sought a sense of sculptural weight and order.

Five Bathers (c. 1890), 28.7 x 20cm (11.3×7.9 inches). By Paul Cézanne.

He liked to take his time and look at his subjects from different angles. “What I wanted was to make of Impressionism something solid and durable,” he said.

The insistent physicality of his paintings perplexed some of the group—the art press too, who repeatedly singled him out for criticism. After a particularly virulent attack in 1877, he resolved to distance himself from Impressionism and began to divide his time between Paris and his father’s estate just outside Aix, where his fealty to Sainte-Victoire really took hold.

By 1882, the mountain had become a mainstay of his practice. He painted and drew it in all seasons and weathers, and with a varying ensemble cast of scattered stones and trees that in the earliest paintings serve as a repoussoir—a compositional trick he learned from paintings by the great 17th-century French landscapists Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, whereby an object in the foreground frames the scene, directing the eye inward.

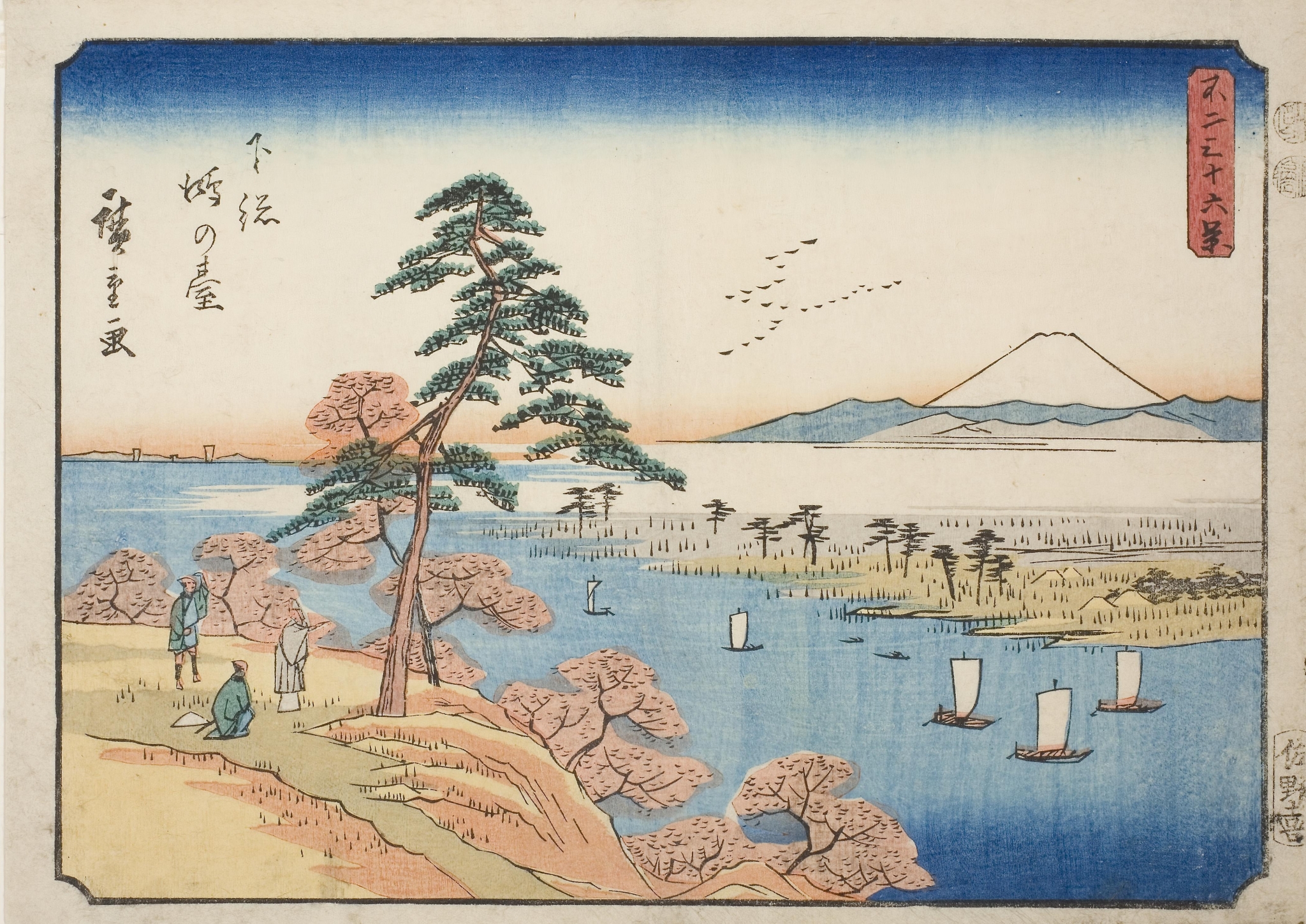

It’s probable that the slight aerial perspective Cézanne preferred was inspired by the woodblock (ukiyo-e) prints of Utagawa Hiroshige, and particularly the series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (1852) 2. Japanese ukiyo-e prints were popular in the West at the time, and Hiroshige was a master of the genre. His supremely evocative landscapes were also an influence on van Gogh, Pissarro, Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard.

2 Konodai in Shimosa Province (Shimosa Konodai, 1852). By Utagawa Hiroshige. Colour woodblock print. The Chicago Art Institute.

In search of Saint-Victoire’s essence—its every shape and colour— Cézanne set up his easel in many different places. In the 1890s he favoured the area around the Bibémus quarry and the Château Noir, a rambling, rundown house about halfway between the town and the mountain, though some examples—Montagne Sainte-Victoire (c. 1890-95) 3 at the Scottish National Gallery, for instance, was painted across the open fields of the Arc valley.

The more he painted it—the harder he strove for the mountain’s fundamental form—the more fragmented, faceted, and eventually visionary Cézanne’s paintings became. “What élan, what imperious thirst for the sun, and what melancholy in the evening, when all that weight sinks back!” he said to the poet Joachim Gasquet in praise of his stone muse.

But the mountain fitted more than Cézanne’s artistic aims. He was a proud native of the Midi and its stalwart presence on the ridge also seemed to embody the rugged, intransigent local character. (The preservation of Provençal heritage emerged as something of a cause célèbre among many poets, writers, and artists in the second half of the 19th century.)

To convey its stately solidity, he increasingly assigned his brush marks a sculptural weight, using them—and the space between them—in the manner of a mason, stacking colours and shapes to slowly shape the painting’s surface.

3 Montagne Sainte-Victoire (c. 1890-95). By Paul Cézanne.

“What élan, what imperious thirst for the sun, and what melancholy in the evening, when all that weight sinks back!” he said to the poet Joachim Gasquet in praise of his stone muse.

The mountain’s Classical credentials—its name is said to memorialise a Roman victory over Germanic barbarians in 102 BC—were probably also part of the appeal it held for him. Cézanne’s esteem for the art of Ancient Greece and Rome is well-documented, and relics of those ancient civilisations stud Provence (think of the arenas at Arles and Nîmes; the Pont du Gard aqueduct near Avignon). In Cézanne’s time, the land of his birth was even hailed as a modern Arcadia—the earthly paradise described in Virgil’s poetry. The critic Gustave Geffroy thought his paintings of Provence evoked an ancient bucolic ideal, while Paul Gauguin described him spending “whole days on mountaintops reading Virgil and looking at the sky”.

In 1901, when he was 62, Cézanne bought a plot of land on the hill of Les Lauves north of Aix that offered a sweeping view of Sainte- Victoire. Almost all of his paintings of the mountain from then on were made either from this vantage point, or another he liked a mile or so uphill. He worked “doggedly”, he told his Paris dealer Ambroise Vollard in a letter the following year. At last, he added, “the Promised Land” was within sight.

It was principally thanks to Vollard (but also the efforts of Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir) that Cézanne’s reputation was finally blooming. In 1895, the dealer had staged a groundbreaking exhibition of Cézanne’s work. Before it, the artist “was considered a madman,” Vollard recalled. “Even the avant-garde regarded him with contempt.” But afterwards, he was perceived as a genius. The artist who released art from the need to make sense in the traditional realistic way. The painter Ker-Xavier Roussel recalled coming away inspired and was among the many artists and critics to make the trek to Provence to meet “the recluse of Aix”—as Roger Fry called Cézanne.

Portrait of Cézanne (1874), oil on canvas. By Camille Pissarro.

The paintings of Sainte-Victoire they found him at work on were almost abstract: the land a heaving patchwork of plains, the mountain vibrating, levitating in light. In his mind, he still hadn’t quite attained “the intensity that is unfolded before my senses,” he told his son. “I do not have the magnificent richness of colouring that animates nature.”

When he visited Cézanne in 1906, Roussel photographed the artist at work in his favourite painting spot above Les Lauves, in a bowler hat and paint-splattered black suit. In one image, he grips a canvas bearing the faint outline of Sainte-Victoire. In the other, he has turned away, brush and palette in hand, eyes fastened on the distant mountain.

Cézanne was out on the hill in October 1906 when he collapsed, lying unconscious in the rain for several hours before a laundry cart chanced upon him and brought him home. “I have sworn to die painting,” he had said to the painter Émile Bernard, and he was to be proved right. A few days after he collapsed, Cézanne died of pneumonia. He is buried at Aix in Saint-Pierre cemetery, on the side of the town that faces the slopes of Sainte-Victoire.