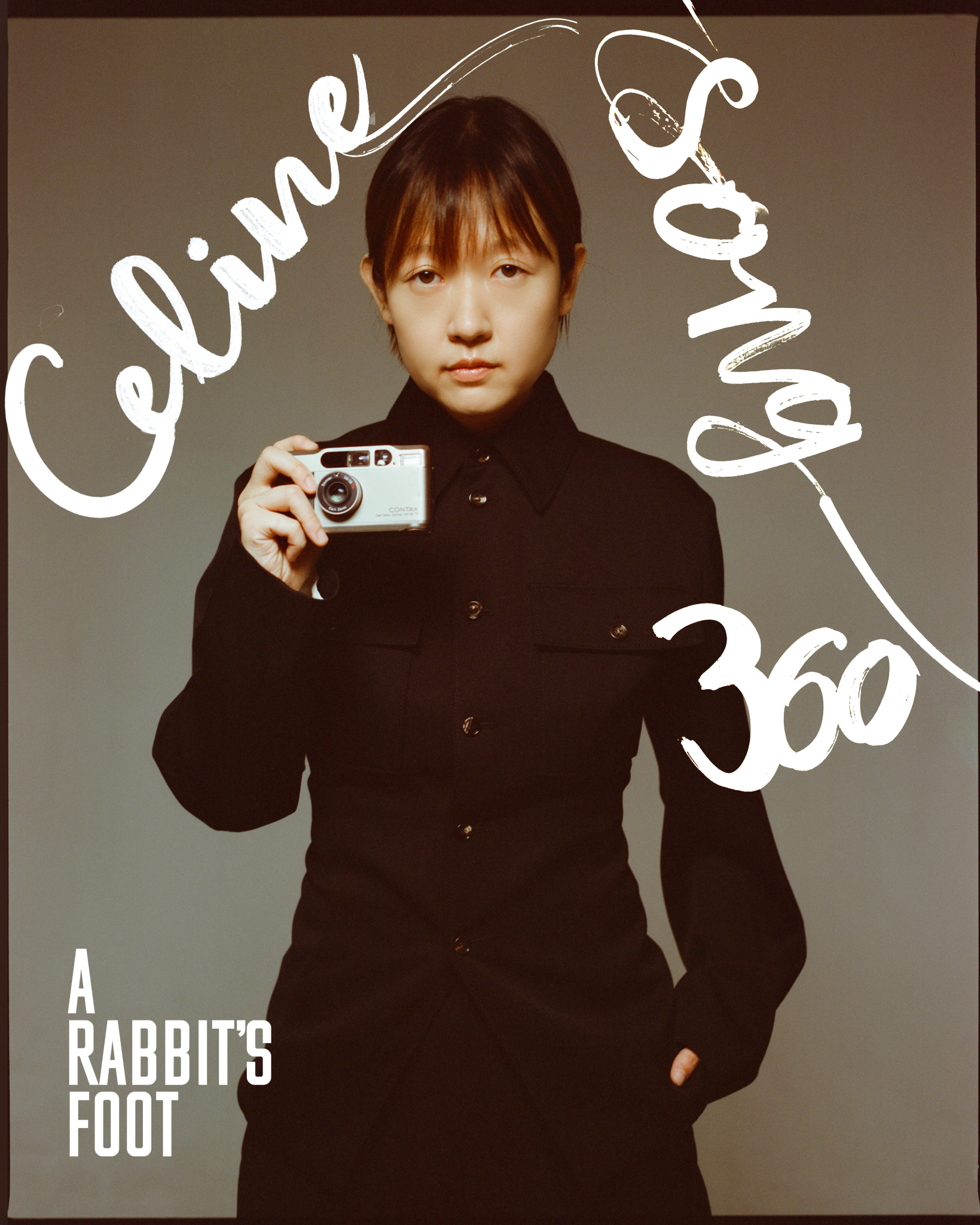

For the inaugural A Rabbit’s Foot 360—a new digital-first extension from A Rabbit’s Foot—we joined filmmaker Celine Song on her home turf for a conversation about finding love in New York City, the elitism of modern dating, and her latest feature Materialists.

“You shut the fuck up! I’m gonna fuck you up!” a man screams into his phone, blustering past the filmmaker Celine Song, who is deep in a monologue about the nature of love. Caught off guard, Song, dressed casually in a Pink Floyd band tee, tries futilely to relocate her train of thought, before bursting into laughter. “Did you get all that?” she asks me. “Very New York, ya know?”

We’re sitting at a sidewalk table outside NoHo’s local Two Hands, where the sounds of New York City are unfiltered and relentless: electric tools from a nearby construction site screech tirelessly, a choir of car horns blare in unison, and chatter from passers-by gets increasingly loud as the city rubs the previous night from its eyes. Among it all, you get the feeling that the famously buzzy metropolis could swallow you up in a heartbeat. And that’s exactly how Song likes it.

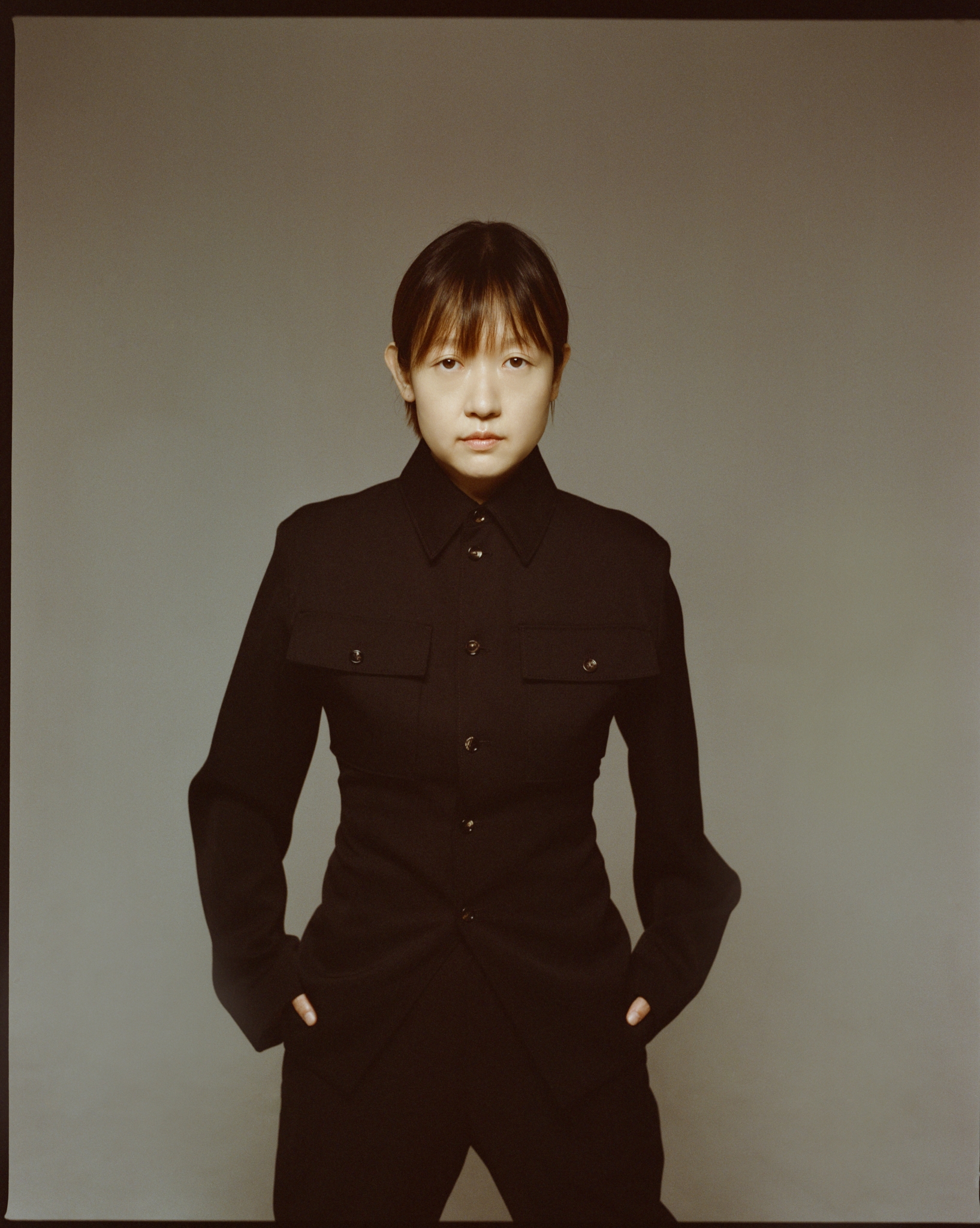

Celine Song wearing Bottega Veneta. New York City, 2025. Creative direction by Fatima Khan, photography by Max Montgomery.

“New York is romantic because you have to accept that your life is very, very small,” she says, when I ask why she chose the concrete jungle as the setting for her films Past Lives (2023) and, her most recent, Materialists (2025). “We’re all here pursuing a dream. It’s not easy to live here. The quality of living is so low that the only reason why you would live here is because you have a dream.” She laughs. “You have to be a romantic. You have to believe that you’re going to make it in the jungle. But you also have to be a survivalist—dog-eat-dog. New York brings together a contradiction of romance and cynicism. It’s an impossible dilemma, but a romantic one, to think that we’re all here because we believe in ourselves, and in the middle of all this surviving, we might still find love?”

Talking with the filmmaker feels like stepping into one of her movies. Like the characters she writes, Song approaches conversation with intimacy in mind, whether the person sitting across from her is a close friend, an actor, or, indeed, a journalist. She listens intently and chooses her words thoughtfully, always maintaining eye contact, always dialled in. During mine and Song’s previous interview in 2023, she discussed the value of in-yun, a Korean phenomenon that refers to a human connection shared across past and future lives. Since the release of the Past Lives, the phrase has become popular among the star-crossed lovers and hopeless romantics of the world. “We can all relate to that feeling that you’ve known a stranger forever,” Song had said. “In this lifetime, this is who we are to each other… You and I are meeting in this professional setting, in this office, talking about this movie for 30 minutes, and then it’s possible that 5,000 lifetimes ago we were parent and child, and 100 lifetimes before that we were mortal enemies… In the next one, maybe we’ll be a little bit closer in our in-yun. Maybe with my future movies we’ll keep talking and it’ll be wonderful… It’s a lovely feeling that makes every encounter in our lives feel meaningful.” It was an inspiring thought then, but only now am I seeing Song put her philosophy into practice: she greets me like an old friend, and we quickly pick up the conversation with the same spirit as we had left off. Shortly after, as I order our coffees from inside, I see a young woman excitedly approach Song, who immediately stands and reaches warmly for the girl’s hand. They talk for a minute or two, and the stranger hurries away with a massive smile on her face. A fan of Materialists, Song later tells me. “And I shook her hand like a weirdo!” she adds, blushing.

Born in South Korea to a graphic designer mother and film-maker father (the South Korean New Wave director Song Neung-han) and raised in Canada, Song has been living in Manhattan since 2012 after moving there to pursue a career as a writer. Life moved fast for Song during her early years in the city. In 2014, she graduated from Columbia University with an MFA in playwriting. She fell in love—marrying fellow scribe Justin Kuritzkes (who most recently wrote Luca Guadagnino’s 2024 films Challengers and Queer) in 2016 after meeting him at an artist’s residency in Montauk. A few months later, she got hired as a professional matchmaker, an experience that would go on to inspire Materialists, which follows Dakota Johnson as Lucy, a Manhattan matchmaker whose job is to orchestrate romances, often driven by money, height, and status. When her wealthy “unicorn” suitor (Pedro Pascal) meets her broke but kindhearted ex (Chris Evans), she must choose between pragmatic luxury and authentic love.

“I was trying to be a good partner and get a day job,” Song says about her time as a matchmaker. “I was thinking a lot about how I feel about love and marriage, and what the point of it is. Of course, half of marriages fail. But the other half is forever. Can you imagine? Loving the same person for a lifetime? If there’s one, it’s a miracle. I was thinking about the weight of that. And now I had this day job where everybody wanted what I had: to marry somebody who simply loved them. But the methodology, how they talked about their intentions in finding that person, had nothing to do with what it was like to fall in love.”

Song describes love as the easiest thing in the world. The tricky part, she says, is the search: “Dating is troubling. It’s a tough, unclear game, and you don’t know why some people win and some people don’t. Of course, you can math it—that guy could get the girl because he’s tall and makes money—but it doesn’t mean there’s love there. There might be, but it’s not guaranteed. Love isn’t about “acquiring” another person. Love is actually so much simpler. It’s an old, holy thing. I understand when you’re heartbroken and scared to try it: it’s terrifying to let your heart speak for itself. But it doesn’t change the fact that love is going to make your life divine if you let it.”

We joined Song on her home turf for a conversation about finding love in New York City, the elitism of modern dating, and Materialists.

Mild spoilers follow for Materialists.

Luke Georgiades: Did working as a matchmaker make you more or less cynical about love?

Celine Song: I think the truth is that love is so much bigger than all of us that it’s always silly to be cynical about it. It only made me firm in my belief that love is something that is beyond our comprehension. It more presented me with an opportunity to contemplate it. Before that, I don’t think I thought of love as a serious subject matter.

LG: Earlier you described love as being both simple and a mystery. Do you see love as a paradox?

CS: The thing about what makes it difficult is its simplicity. Dating is complex. You have to consider the marketplace and what space you fill in that marketplace. Love, though, is surrender. We live in a modern world where every single thing in our lives feels controllable, and we’re asked to control it, and you’re better at your job if you’re able to control it: emotions, spreadsheets, values, yourself, other people. It’s hard to suddenly change gears and accept that love is the only thing that is about letting go of control, that this thing that is not tangible called love is going to be the thing that saves us. I wish I had better news. I wish I could say that if you could afford that Birkin bag then you will be happy, because it somehow feels more achievable. But the only news is that love, this thing that is priceless and like lightning if it strikes, is completely worth believing in. I’m married, and I wish I could tell ya that having someone love you like Justin does is not worth it, but it is.

LG: For Materialists, you’ve mentioned wanting to make John’s space in front of the bodega feel romantic. It’s easy to make a beautiful restaurant or apartment romantic. How do you do it for those less typically romantic New York spaces?

CS: Because they are romantic, but we’re informed by the way the world teaches us what romance is. We grow up watching so much media about love, and it’s often defined by open presentation of wealth. The way that starts to seep into our psyche is like, well, romance must be for the wealthy.

LG: I know many people, including myself, who have experienced that—not even attempting love because of the amount of money it takes to do so.

CS: But love is one of the only truly spiritual things. It’s untouched by the material. You can fall in love in front of a bodega truck. You can. Wealth is the great drug of our time. There was a time when sex was the great drug of our time, or, well, drugs were the great drugs of our time. Right now, it’s wealth. Right now, the sickest, darkest thought is feeling envy for the wealthy. That’s why so much media gets made about dismantling the wealthy, or falling in love with the wealthy. Any kind of version of the American Dream concerns working hard and jumping your class, promoting yourself to a better life. That dream has been so demolished that one of the only ways it really exists is either hitting it big on social media and turning yourself into merchandise, or marrying rich. So why not get that boob job, or lip job, or leg surgery? Why not do that to yourself to be better merchandise for someone who will change your lot in life? It’s a scary descent into total commodification of the self and each other, but how can you judge them when it literally changes your value?

“Love is one of the only truly spiritual things. It’s untouched by the material. You can fall in love in front of a bodega truck.”

Celine Song

LG: There’s a moment in the film where it’s revealed that Harry has had height-altering surgery. There were a few men, notably, in my screening who snickered at the sight of that.

CS: It’s uncomfortable to admit that these value systems have become a part of our bones. Because everyone who is deemed worthy of being seen on screen is six foot or taller. Half of Americans are under five-eight, and above that, a huge percentage of those men don’t meet six feet. When I was working as a matchmaker, everyone’s requirement was that the man be a minimum of six feet tall. What do you mean, the minimum six feet? That’s a very tall dude. That’s one of the tallest men in America! There’s no reason for that to be a part of looking for the person you love. Most of the men in your screening were likely not six feet tall. But when you see Pedro bend down, it doesn’t matter how un-superficial we think we are, you still see the way this person loses value. They laughed because the image of a five-six man hitting on a woman makes no sense to them. We see dehumanisation of that kind all the time. Let’s say you become very famous and rich because you became a TikTok star or married someone wealthy—we’re still not kind to those people. We’re even meaner. And then we go, well, that’s the cost of it. We hate you because you did all the things that we asked you to do to feel valued. It’s a vicious cycle. Where can love exist in the middle of that? That’s what we’re here to do, so what happened?

LG: I wonder if casting played into that idea at all? Pascal, Johnson, and Evans are all very commercial representations of what beauty looks like right now.

CS: Their looks are a part of the story. I wanted to cast them because all three of them deeply understand the experience of being seen as merchandise. I think Pedro would say he’s not the Mandalorian. Chris is not Captain America—he’s not an action figure. Dakota? That’s how she came into this whole game, with Fifty Shades! That’s what it means to be a person who we deem worthy of looking at. You experience intense love from the world and intense hatred. In this movie, I’m offering them a chance to be treated like a person. The way Lucy is able to have her happy ending is to admit that the way she has been treating herself and others simply won’t hold. The value system has to break down. I’m asking them all, and the audience, to let go of that.

LG: I know you used Broadcast News, which I consider one of the greatest romantic-comedies of all time, as a reference for Materialists.

CS: It’s one of the great representations of a woman who works, and It’s one of the greatest movies about journalistic integrity. Our world right now is all about that: the fake news, the manipulation of the public through the media. And some of the most romantic lines in that film are journalism related. “I’m in love with you. There, I buried the lead.” In another movie, that would be so silly. It wouldn’t be so perfect. I was thinking about that when it came to the financial language in Materialists. The most romantic line in Materialists is “how would you like to make a very bad financial decision?” and you’re like, in another movie, it sounds like it’s out of Succession. It wouldn’t work. In Materialists, they’re always talking in financial terms, and they’re all crushed by it. How many dating conversations include the phrase “what are you bringing to the table?” “What are you offering me?” Why are we talking like we’re having a financial meeting?

LG: Tell me about the significance of the New York City stoop, which both of your films feature heavily.

CS: The stoop is a way to turn this giant, busy city into a private room of your own. I’m sure the owners of those buildings will disagree, but love is free. I love New York for that reason. There’s so little privacy here, you’re living with people in very close quarters 100% of the time. It’s why the concept of in-yun was so important to find in New York, or any kind of city where you’re going to encounter hundreds of people just by walking down a block.

LG: What makes someone a New Yorker?

CS: The moment you stop thinking you’re going to move out you become a New Yorker.

LG: How has your relationship with the city evolved?

CS: It’s gotten better, especially as my economic situation has improved and we’ve been able to pay higher rent, but it was really hard when we couldn’t. Me and Justin made, collectively, $25,000 a year. We filed taxes and we were like, there’s no way we survived on this little money. But we did—you survive, somehow.

Materialists is out in UK and Irish cinemas on 13th August.

Creative Direction: Fatima Khan

Interview: Luke Georgiades

Photography: Max Montgomery

Videography by Matilda Montgomery

Video Editor: Alice Wade

Video Production: Luke Georgiades

Photography assistant: Chase Elliot

Stylist: Maurice Diallo

Styling assistant: Triet Vo

Hair & Make-Up: Jessi Butterfield

Sound (video): Sebastian Holst

Title treatment: Broad Peak Studio

Creative assistant: Kitty Spicer

Full look by Bottega Veneta

A Rabbit’s Foot 360 is a new, digital-first extension from the team at A Rabbit’s Foot. Each month, we present an exclusive cover feature that spotlights and celebrates an artist at the forefront of culture. Through high-quality photography, film and an in-depth print interview, A Rabbit’s Foot 360 tells their story, gaining insights into their creative process, personality and world-building. #ARF360