A Rabbit’s Foot Features writer Luke Georgiades and Creative Director Fatima Khan joined the filmmaker in his native New York to discuss celebrating life’s great losses, the beauty in an MMA tap-out, and Dwayne Johnson taking a beating as Mark Kerr in The Smashing Machine.

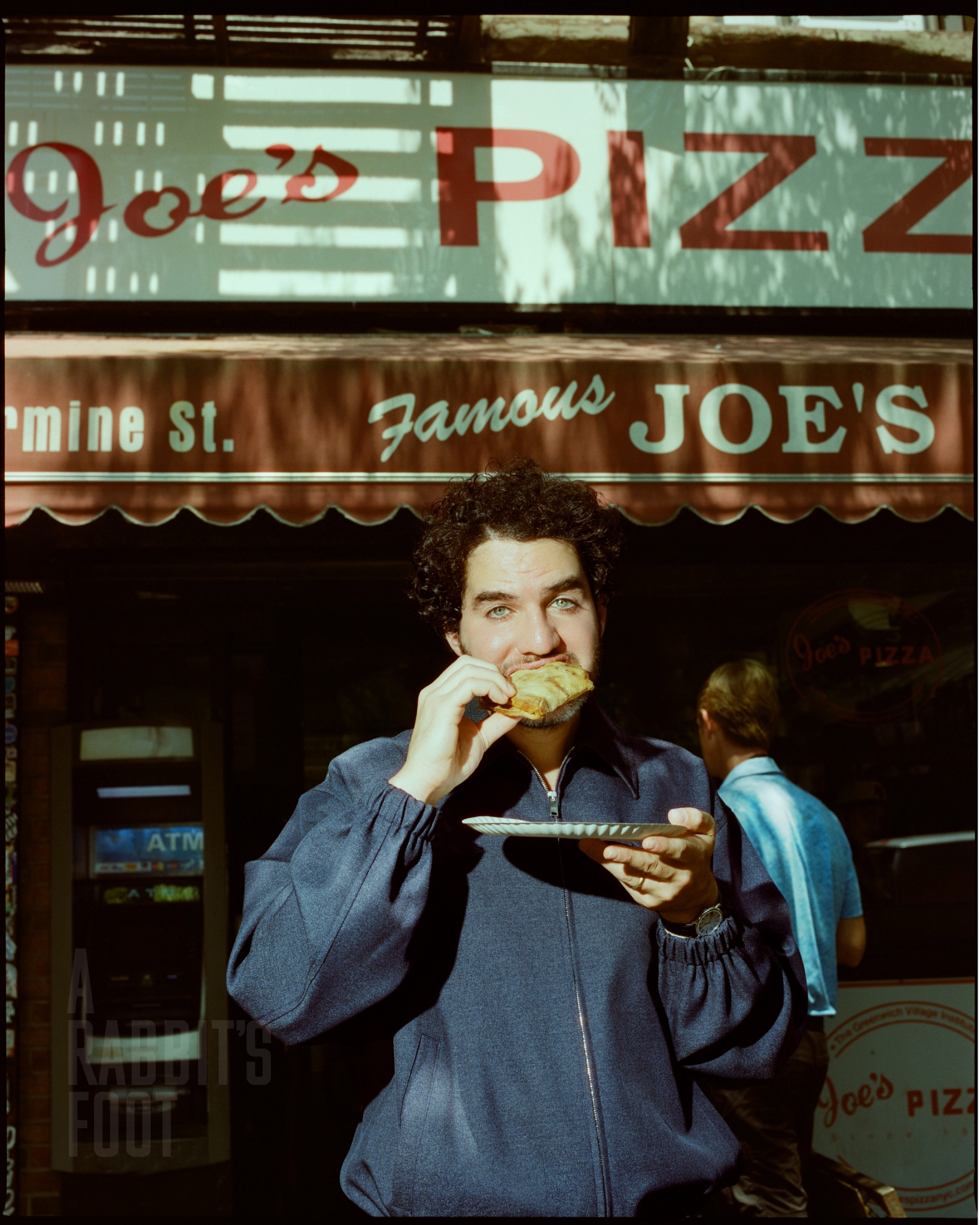

Benny Safdie is serving us a slice of his New York City.

We’re at Joe’s Pizza on Carmine Street, Greenwich Village—a legendary institution that, I’m told, every New Yorker worth their salt has dined in at some point or another. Teeming with an infinite stream of customers, the only thing more famous than a slice from Joe’s are the names who have devoured them, with the walls inside lined with framed photos of some of the famous patrons who’ve stopped by over the years. Everyone from Matthew McConaughey and A$AP Rocky to Kim Kardashian and Bill Murray has tucked into one of Pino “Joe” Pozzuoli’s pizzas. Safdie’s face isn’t on the wall just yet—but give it time. A few weeks after we meet, the 39-year-old filmmaker will ascend the stage at the Venice Biennale to accept the Silver Lion for Best Directing for his first solo feature, The Smashing Machine. An achievement Safdie never “in a million years” thought he would win, he tells me during a later conversation. But here and now, dressed casually in jeans and a navy blouson, he remains indistinguishable from the crowd—just another New Yorker enjoying a slice on the sidewalk.

It’s a concept that intrigues Safdie: that every anonymous face on the street carries a lifetime of triumphs and failures. The idea is integral to the story of MMA [Mixed martial arts] pioneer Mark Kerr, the life of which Safdie’s The Smashing Machine is based. The film—aptly starring WWE wrestler-turned-Hollywood megastar Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson—follows Kerr’s failed comeback attempt during the 2000s, which ultimately led the former fighting champion to fade into near-total anonymity, despite having helped lay the groundwork for what is now one of the most popular and lucrative sports on the planet. “Mark Kerr gave an interview where he was talking about how he was working at a car dealership and the customers didn’t know what he had done in his life,” Safdie tells me. “They didn’t know that he had won three championships. They had no idea. That could be anyone.” During his acceptance speech in Venice, he refers to The Smashing Machine as “an exercise in radical empathy,” thanking Kerr for “living his life so that we could feel it.”

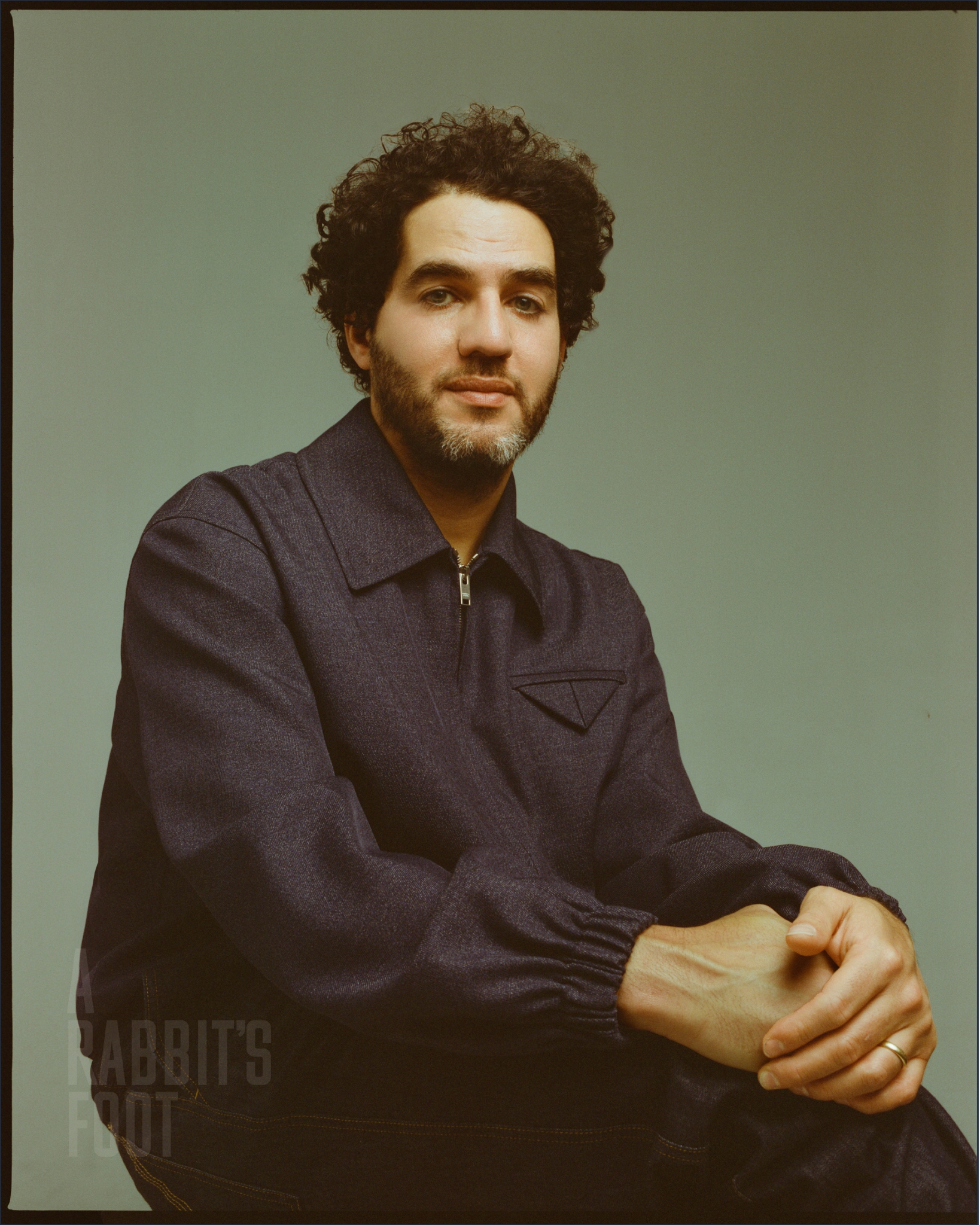

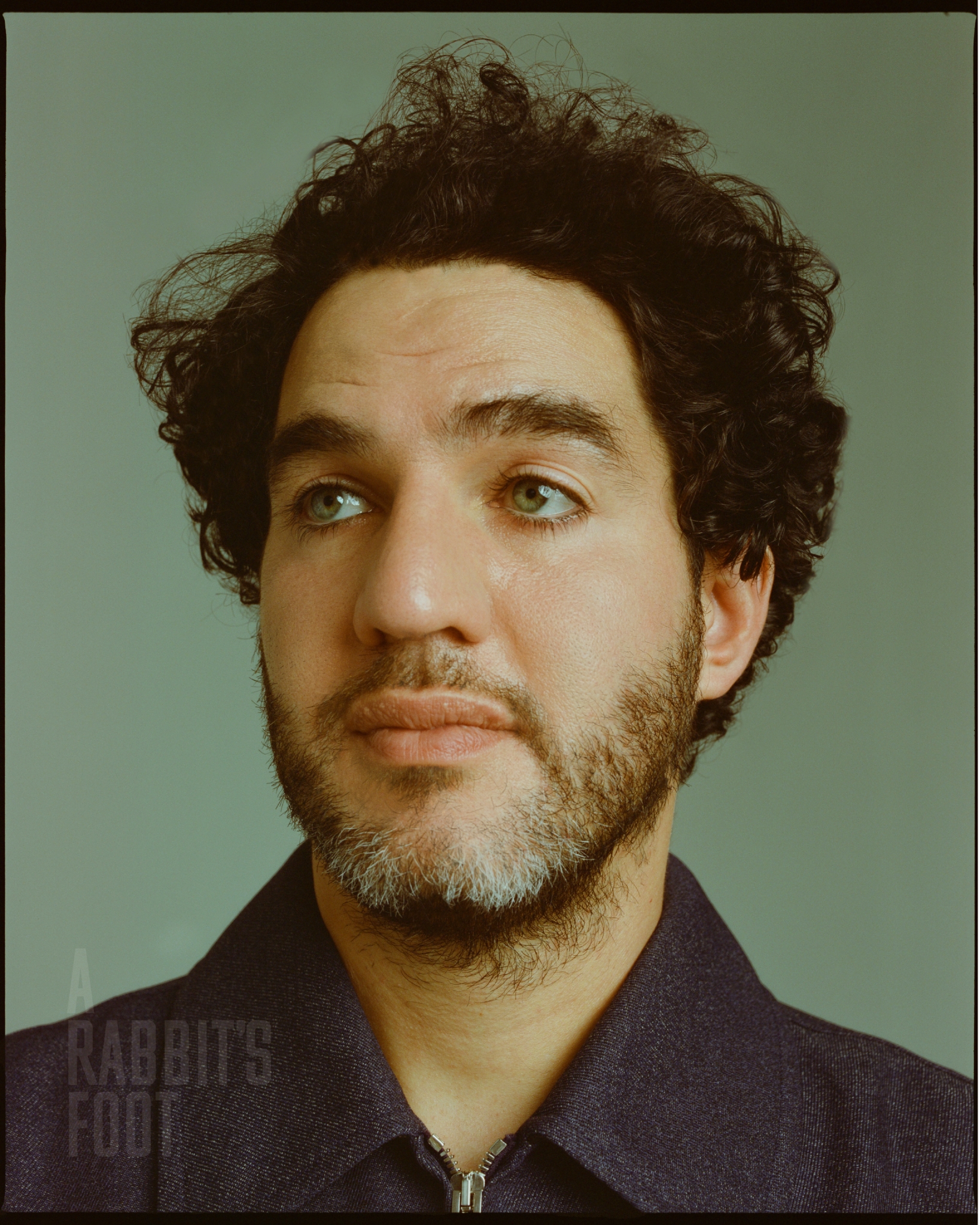

Benny Safdie wearing Bottega Veneta. New York City, 2025. Creative direction by Fatima Khan, photography by Max Montgomery.

Safdie is always on the lookout for stories hidden beneath the noise of everyday life. At one point, as we huddle around a couple of pizza boxes balanced on tiny bar stools, I notice him sprint away from the group. He disappears around the corner and returns moments later carrying a small film camera. He’s found an image: a man in his early 70s, parked on the curb outside Joe’s, one leg casually draped over the open door of his work van with a pizza box resting on the dashboard. Safdie carefully and unobtrusively finds his angle—pointing the camera at the man’s reflection in the van’s rearview mirror—and takes the shot. Then another. Once satisfied he’s captured the moment, he slips seamlessly back into the flow of our conversation.

Later, he takes us to the Walter Reade Theatre at Film at Lincoln Center—another iconic spot, and Safdie’s favourite cinema in the city. “Me and my brother [Josh] shot a scene from our very first movie, Daddy Longlegs, in this theatre.” He recalls. “The lead actor [frequent Safdie collaborator Ronald Bronstein] was a projectionist here.”

The Walter Reade is midway through a retrospective celebrating the life and career of the late Gene Hackman. Safdie is due to catch a plane that evening, but expresses relief that he’ll be back in town before the theatre’s screening of Scarecrow, which he calls one of the all-time great Hackman films. The two FLC staff members on duty nod in enthusiastic agreement.

Unlike at Joe’s, blending in here isn’t quite as easy for Safdie, who, after well over a decade in the game, has gradually cemented himself as one of contemporary cinema’s most trusted and exciting voices. While chatting with staff in the lobby, he finds himself standing in front of a giant screen photo of him flashing a peace sign next to a grinning Emma Stone. “Yep, there I am,” he jokes, self-deprecatingly. It’s not long before one of the theatre employees produces a Criterion edition of his 2019 phenomenon Uncut Gems and politely asks for an autograph. Safdie happily obliges, taking the pen and scribbling his name across Adam Sandler’s glinting face. “I don’t ask filmmakers to sign stuff often,” the employee had confessed earlier. “But this one is special.”

The Smashing Machine marks a series of firsts for Safdie: it’s the first feature he’s made without his brother Josh, who is equally busy etching out his own solo legacy with the upcoming Marty Supreme (also a sports biopic). It’s the first he’s made purely outside of his native New York, shooting instead in New Mexico, Vancouver and Tokyo (Japan, he tells me, was one of the early supporters of MMA. “It was banned in the US at one point, but in Japan 90,000 people would pack into the Tokyo dome to watch these fights.”). Safdie is quick to remind me that The Curse, the acclaimed TV show that he co-created with comedy maverick Nathan Fielder, was also set outside NYC. “What I learned from shooting in New York is that it kind of prepares you to shoot anywhere,” he says. “If you’re able to perform underneath that kind of pressure, then you can take that with you anywhere.”

It’s also his first collaboration with Johnson, who was the one that brought the idea for The Smashing Machine to Safdie in the first place. The pair have already announced their next project, an adaptation of Daniel Pinkwater’s novel Lizard Music. “I told Dwayne I wanted to do what we did on The Smashing Machine, but for everybody, you know? It’s a family movie. I want families to have real conversations with their kids afterwards.”

Still, certain curiosities remain imprinted on Safdie’s artistic mind, tracing back to some of his earliest work and remaining omnipresent in The Smashing Machine. Chief among them is his fascination with honouring life’s great ‘losers’: those who strive for greatness but are ultimately rejected by it—the Lenny Cookes (Lenny Cooke, 2013), the Mark Kerrs (The Smashing Machine), and even the real-life Howard Ratners (Uncut Gems) of the world.

“Winning is a fleeting thing, but loss is where humanity is,” Safdie says. “Winning can’t sustain you through life. If you’re trying to do that, you’re setting yourself up for failure… No one likes to talk about loss, because it makes you feel bad. The Smashing Machine explores the possibility of a loss making you feel great.”

Safdie spoke with A Rabbit’s Foot about paying tribute to the losers, the beauty in an MMA tap-out, and Dwayne Johnson taking a beating as Mark Kerr in The Smashing Machine.

Luke Georgiades: It seems like you’re currently having a lot of fun with all the possibilities at your fingertips. What kind of creative space are you in right now?

Benny Safdie: Yeah, whatever I’m finding exciting, I’m going to go and do it. When [Adam] Sandler calls you and tells you, “I want you to be the bad guy in Happy Gilmore 2, you’re like, “oh my God, yes.” And I’m going to have the best time, I’m going to work as hard as possible to do the best job I can on a different style of movie than I’d done before, and I’m going to learn from that experience. I was editing The Smashing Machine while I was working on that. I was working on the score while looking like Frank Manatee [laughs]. That was humbling for me. Even though I was working on this thing of my own, I was still going to set and listening to other people, and I had to do what they said. It gives you perspective.

LG: What did you want to do differently to separate The Smashing Machine from your typical rise and fall sports biopic?

BS: What I became really obsessed with was the people involved. There are beautiful films like Requiem of A Heavyweight and Fat City that really get into the ham-and-eggers—the people that are working just to get just enough food to get by. I wanted to make a movie about what it actually felt like to be that person. What does it take to go through the bullshit of life and then get in the ring and put it all on the line? You think you understand this person, you judge them based on who you think they are and what they do, but just because this guy’s big and strong it doesn’t mean he has the ability to not feel internal pain. I also liked the fact that the fighters all really cared about each other. I wanted to show that affection amongst them. The fact that these guys could be so empathetic to each other after being so violent. That’s something that maybe we could all learn from.

LG: Do you feel like that camaraderie between fighters has been lost over time?

BS: No, if anything, that’s a real part of it that a lot of people don’t know about. There’s a real connection amongst these men and women. They’re training with each other everyday, they’re pushing each other to greatness. I loved the idea that another fighter could be happy—genuinely happy—for another person winning. This is supposed to be their enemy, but they can still look at that other person and say, “it’s yours, go get it.” They’ll beat the crap out of each other, and then at the end they’ll check in on each other. The tap out is a beautiful thing in MMA. You’re getting them to a place of, “I could destroy you right now, but I’m giving you the choice of mercy. I’m not breaking your leg, I’m not ripping your arm out of its socket. I’m telling you I can—you know I can—but give me a little tap and it’s all over.” That’s the most beautiful thing in the world.

LG: I rewatched Lenny Cooke and I couldn’t help but connect the dots between these two athletes who were, in some ways, rejected by their own destiny. What has that theme meant to you?

BS: They’re totally connected. The time of Lenny Cooke was the same time period as Mark Kerr. It was a time period where people were on the cusp of something much bigger than where they were. Had they been a couple years later, their whole lives would be different. That’s a fascinating point to find somebody. Here you have someone who laid the groundwork for something, and couldn’t reap the benefits. A part of wanting to make this movie is highlighting these people and saying, hey, remember their faces, remember their names. Mark Kerr gave an interview where he was talking about how he was working at a car dealership and the customers didn’t know what he had done in his life. They didn’t know that he had won three championships. They had no idea. That could be anyone.

There’s a book of essays edited by Mary Pylon and Louisa Thomas called Losers: Dispatches From the Other Side of the Scoreboard, about all of these people in sports who lost. And they say that winning is a fleeting thing, but losses are where humanity is. When you win, you feel good for that moment in time, but then you gotta go back to your life. Winning can’t sustain you through life. If you’re trying to do that, you’re setting yourself up for failure. You’re going to be chasing that feeling over and over again. No one likes to talk about loss, because it makes you feel bad. The Smashing Machine explores the possibility of a loss making you feel great. If you look at It’s A Wonderful Life, George Bailey doesn’t gain anything by the end of the movie that he doesn’t have at the beginning. The only thing he gains is a different perspective on life. I wanted to make a movie about that. I got to talk to Mark. How he’s recovered, how he genuinely feels bad about some of the things he did in life and wants to be a better person. This guy came out the other side and he’s okay.

LG: What do you think is something that people misunderstand about Dwayne?

BS: They kind of assume that he doesn’t have an interior life. Just like Mark Kerr. They look at him and they think he’s this big, strong guy, he’s performing for us, and they take for granted that he had a crazy upbringing. His father was a wrestler, but he was a wrestler at a time where he was travelling from small town to small town to small town. He had a hard life. He’s seen some shit. And he hasn’t had the opportunity to show it. You can’t play this role with such emotion if you don’t know what these things feel like. There’s another side to these titans of our culture. We like to think we know them, but they’re constantly searching for something in themselves.

LG: Dwayne mentioned in an earlier interview that you didn’t want to fake the fight sequences.

BS: There’s a lot of things that you can do with special effects in a fighting movie, and I didn’t want to do any of them. I wanted to do it the old fashioned way: with blocking and camera and stuff like that, so while there’s a lot of grappling and getting thrown on the ground, they’re not actually getting punched. But in the movie there’s a fight where Mark’s body gives out and he can’t move, and he’s getting punched in the face, in the head, kneed in the stomach, over and over and over again. When you see that, it’s almost like, well, you kind of have to see that, and it’s got to look and feel real. Dwayne said that in wrestling they call it ‘laying it in’. He said to the guy, “you gotta hit me. “I know you’re a professional fighter, so don’t give me 100%” [laughs] “Give me 80%.” But the guy didn’t want to hit him. [Former MMA fighter] Bas Rutten was overhearing the conversation and shouted, “he’s the fucking Rock! Punch him in the head! Do what you gotta do!” [laughs]. But you can see it in that moment that both Dwayne and Mark just got destroyed. I said to him, “I would love to not cut away at this moment. I would love to see it and be in it with you.” And he really took those punches.

LG: It sounds brutal, too.

BS: I was obsessed with the sound mix. We had a silicone replica of Dwayne’s body that we would smack and record. The punches are layered with so many different sounds. There’s the first punch, then the sub punch, then the sub sub punch, so you’re hearing the rapid succession of fist, flesh and bone—the timeline of a single punch. And each one has a different sound. It was a difficult mix. Having the music layered in with the real music from the fights. We would iron it out over and over again, down to the specific directional microphone that I knew you could point at anything and pick up the sound. There’s no ADR in that ring. I hate ADR. I don’t like doing it, it never sounds right. We had microphones everywhere. On everyone. In the corners of the ring. Under the ring, so when they got smashed down you heard the impact.

LG: I’m glad you mentioned the music. Nala Sinephro is one of my favourite artists, period, right now.

BS: She’s amazing isn’t she? The sounds that she makes when Mark loses, or when he’s doing drugs. She got into his head. She said, “I feel like I understand this guy. I felt like a wrestler.” She would tell me about how she’d play the harp and her fingers would bleed. She understood Mark’s obsession. She made music that I call an intense psycho-analysis of what’s going on in Mark’s head. She is unbelievable.

LG: Lizard Music was announced recently. It sounds unlike anything you’ve ever done before.

BS: I’m so excited. I love the author Daniel Pinkwater, I’ve gotten very close with him. He said to me, “you know, the kids who read my books, they’re going to be okay. They’ll know when they’re being sold a bag of goods.” I thought, that’s awesome. There’s something beautiful about this book in particular. When I read it to my kids, and the kind of conversations it started, it was special. I told Dwayne I wanted to do what we did on The Smashing Machine, but for everybody, you know? It’s a family movie. I want families to talk to their kids and have these real conversations afterwards. He’s losing weight. He’s playing a wild character in this movie. It’s exciting to go on another journey with him that on the surface sounds nothing like The Smashing Machine, but it’s almost exactly the same: we’re both still just trying to understand ourselves. I can’t wait to make it. I can’t wait to find the lizards.

Interview by: Luke Georgiades

Creative Direction: Fatima Khan

Videography: Matilda Montgomery

Photography: Max Montgomery

Video production: Luke Georgiades

Video assistant: Sebastian Holst

Photography assistant: Chase Elliot

Stylist: Maurice Diallo

Stylist assistant: Campbell Brown

Groomer: Rheanne White

Shoot assistants: Triet Vo

Digital Editor: Kitty Grady

Title treatment: Broad Peak Studio

Creative assistant: Kitty Spicer