Skinamarink, it turns out, is not the name of a monster from a Norse folktale. It is a children’s song, originally written in 1910, that has worn a variety of names over the decades. Among them: Skidamarink, Skid-dy-mer-rink-adink-aboomp, and my favourite –Tiddley Winkie Woo. The film – Kyle Edward Ball’s first feature – is named after the song because it is about the uncanny textures of childhood memory. And although those textures are brilliantly and innovatively evoked, texture is all that is achieved. Skinamarink, in other words, is a spectacular example of do-it-yourself formalism, and demonstrates the persistence of horror as a success-space for low-budget experiments; but as is often the case with excessively image-oriented films, the spectacle lacks supplemental fibre.

It is 1995, we are in a family home strewn with Lego and stuffed toys and we glean that four-year-old Kevin has fallen down the stairs while sleepwalking. Dad is on the phone, he says that Kevin has hit his head. A while later, Kevin and his sister Kaylee (six) wake up in the middle of the night to find that Dad has seemingly vanished. They decide to watch cartoons, but other things are vanishing too: windows, doors, the toilet. If this was not already enough to frighten the bejesus out of them, it turns out that a dark presence is in the house, that it can communicate with them, and that it is probably responsible for the disappearances.

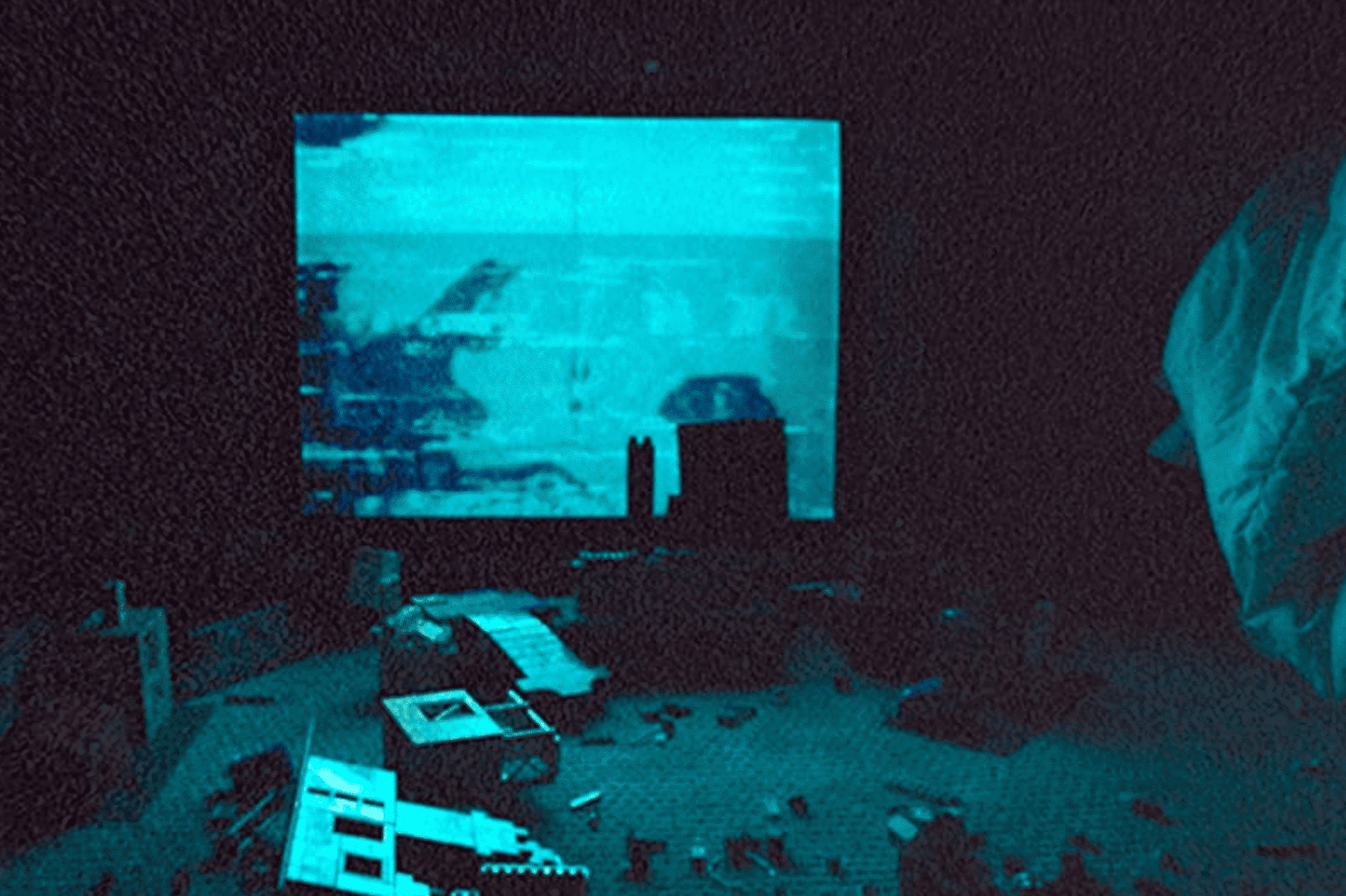

Strange events ensue: Kaylee goes upstairs and finds that (both) of her parents are in the master bedroom. Dad tells her to look under the bed, where there is only darkness. Mum says “close your eyes” and “I love you”. Then they both (you guessed it) vanish into thin air. Eventually the voice takes Kaylee away and tells Kevin to stab himself in the eye. When he goes to find Kaylee, he finds her featureless. The film then leans into a kind of meaning-entropy. The cartoons on the screen start to skip in an endless loop, half-impressions swim in a buzz of visual noise, and the logic of the space contorts itself. It was very hard to know what was going on already, but by the end, we realise that might just have been the whole point.

As a consequence, it feels a little superfluous to report the narrative. Skinamarink is not really a film of plot, but a film of effect. A particular mood is produced from the very beginning and then sustained. Although self-presenting as a horror (and some of the aesthetic markers are there), it is better described as a study in the uncanny. What we experience in Skinamarink is what we knew the world to be like when our infant imaginations coloured it with enchantment. Sometimes this was good, sometimes it was bad, and very scary. For most of the film’s scenes, in fact, I recall much less being hooked in by default narrative reflexes: ‘how will the kids overcome this challenge?’, ‘when will the monster appear?’, ‘what will happen next?’ – and more being nudged into a subtle trance. I thought about Jeanne Dielman (Chantal Akerman is an influence of Ball’s, it turns out). Both films sit away from the traditional contours of story, but in the case of Dielman, there is a momentum which moves along an axis of discomfort, culminating in miserable violence. Skinamarink is arguably flatter: there is just mood.

This is an interesting formal conceit. The film is furnished, for example, with very little in the way of jump-scares. There are a couple, but screaming (another horror trope) is entirely absent. The register of the children never rises above a nervous whisper. Yes, this can elicit somnolence, although arguably the film is best encountered having just woken up from a nap in front of the TV, late at night – there it is flickering on the screen. The deeper problem is the tension between the (admittedly striking) grain and technical ambition of the film, and the broader language it has chosen to articulate itself in – which is the language of cinema, and not the language of sheer abstraction. After stepping out of the movie into the harsh daylight, I did find myself wishing that Ball had directed a fifteen-minute version of this as the dream-sequence in another movie, one with a wholly unalike tone.

There is much to celebrate about Skinamarink, especially as a debut. It was made on a shoestring budget, with Ball and his team renting all the equipment. It cost fifteen thousand dollars to make, and so far has grossed two million. It reminds us of the vitality of horror, and the capacity of the genre to generate blockbuster numbers (Skinamarink less so, but Blair Witch, Paranormal Activity) with meagre means. Ball’s story is also a very modern one. The film was originally a fifteen-minute proof-of-concept on his YouTube channel, which was devoted to horror shorts. Each short was inspired by the childhood fears related in the comments of the videos. One memory appeared a lot: ‘I was most scared that I would wake up in the middle of the night and my parents were not there, there is a presence in the dark’ – this became Skinamarink. The finished product, then, is a kind of ghostly silhouette cast by the YouTube comments section; I can’t help but like this.

The audio-visual trickery is also ingenious. The sound is edited with bewildering results, and is sometimes fully drawn away, leaving only subtitles behind. At points, the lo-fi granularity of the footage coils into a kind of smoke, where the vague figures of the children seem to jump in and out of focus. We are never sure if they are there or not, and it really does recall the feeling of gazing into the dark as a small and scared thing, for whom Mum and Dad are gods.

I end on a positive note intentionally. As a collection of images, Ball’s first film is deeply intriguing and unmistakably original. This alone is not what makes great cinema. Nonetheless, I am glad that films like it exist, and that it is still possible for them to exist. Many of the shots were unlike anything I’d seen before, and I hope that next time, with better-lined pockets, he produces something we remember for more than its complexion and timbre.