As if it was etched in fate, there’s an inevitability to the idea that Ai Weiwei was always going to find himself entwined in a marriage of art and activism. The son of Ai Qing, one of China’s most revered poets, the artist and filmmaker’s taste for political resistance via artistic statement seems a matter of inheritance that was decided from birth. In his book 1000 Years Of Joys and Sorrows, he confirms as such, detailing a childhood spent in exile after Qing fell on the wrong side of Mao Zedong and was subsequently banished to “Little Siberia”—a remote region of North-West China.

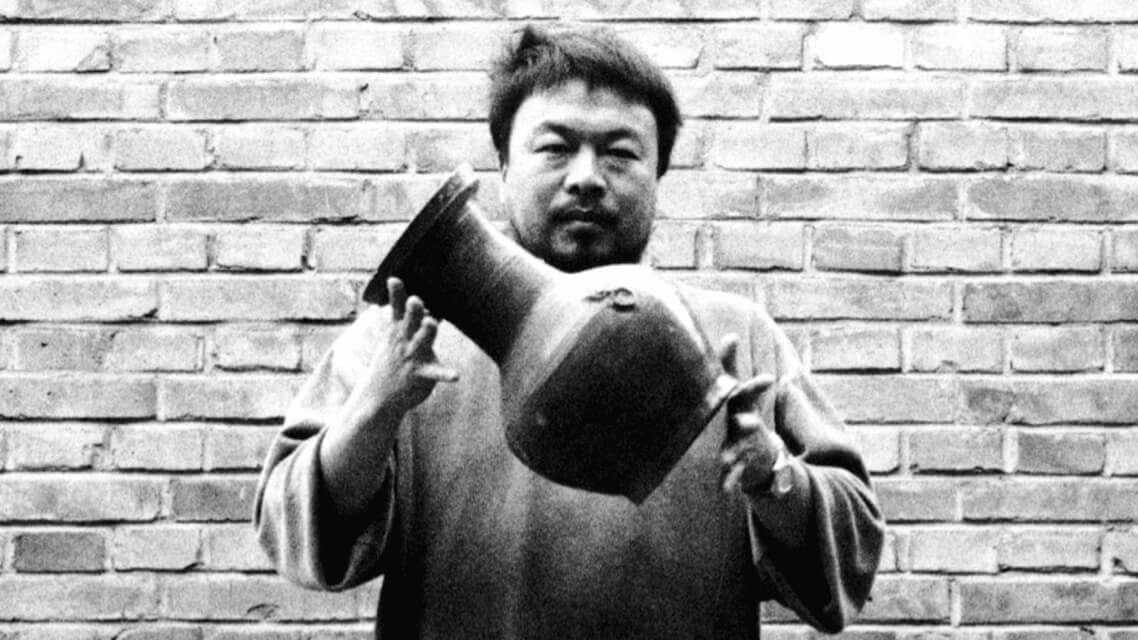

Over the years, despite falling foul of the Chinese government himself and briefly being held as a political prisoner, Ai’s middle finger has kept firm aim at the establishment, sometimes quite literally—his photographic series Study of Perspective is the “fuck you” felt around the world, as he flips the bird in the direction of various global landmarks including the White House, Trump tower, and multiple locations throughout China. The series acts as a disarmingly simple act of vitriol against the regime that feels both gloriously tongue-in-cheek and a defiant reclamation of power for the people. Many of his most famous works have been similarly executed: in 1995 he released three photographs that captured the artist dropping a priceless two-thousand-year-old Han Dynasty urn (the artwork, aptly titled Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, is a follow-up to his 1994 work Han Jar Overpainted With Coca-Cola Logo). More recently, in honour of Human Rights Day 2022, Weiwei took to Hyde Park’s legendary Speaker’s Corner to distribute blank sheets of A4 paper, signed by him with invisible UV link in what he describes as “an ironic symbol of resistance”; a comment on the frustrating nature of political expression in China and beyond.

As a director, his most recent documentaries epitomise the power of filmmaking as arguably the art world’s greatest tool for empathy. Cockroach is a heart-wrenching portrait of the 2019 Hong Kong riots, documented unflinchingly from the frontlines, while Coronation, filmed in secrecy by the ordinary city dweller, provides one of the only documents of life inside Wuhan during the Covid-19 pandemic. These records—along with an array of his other works, including Rohingya, Weiwei’s quiet meditation on the nature of the refugee crisis—depict in heart-wrenching intimacy the hope, despair and resilience of peoples in crisis. Movies don’t get any more essential than this.

Why was it so crucial for you to document the different perspectives experienced inside Wuhan during the pandemic?

I have come to realise that the inception of the pandemic in Wuhan would remain obscure and difficult to clarify. Its complexity would exceed our imagination. Even though it’s already been three years since the pandemic, we still don’t know the virus’ origin, development, and impact on our future society despite diverse statements from scientists and governments. Documentation would be the only possibility to leave an original record and a basic measure to fight against forgetting and erasing.

You’ve never been a stranger to film as a medium in which to express your art, having completed over thirty films throughout your career. Over the past several years your output has been more prolific, urgent, and large-scale than ever. What is it about filmmaking that makes it the most essential method for telling these particular stories?

When we face major changes in society and our own life, we puzzle over them and struggle in our respective ways. Making documentaries is my attempt to understand the new environment around me. This reaction is my efforts to contribute to society as an individual, and minimal expression of myself. Today we have the chance to document and disseminate our expression, and I am just making use of these new possibilities.

Cockroach touches heavily on the use of social media to organise protests, and you are also known to have used social media in a big way to express yourself – what are your current thoughts on social media as a political tool in 2023?

I spend a lot of time on social media and use it very frequently, but there are two phases in my engagement with social media: first in China and then outside China. In China, I once described social media as a glimmer of light in a dark, iron-barred room. That was my understanding of social media because it is a tiny space for information and free expression in a harsh authoritarian society.

The biggest doubt about social media occurred to me after moving to the West. I saw that although social media was widely accepted and freely used, information and expression have been drowned in different kinds of loud noises and merged with entertainment. These days, we can observe that social media has become a political tool, and its reflections upon humanitarianism and the effects of such reflections are very limited. The strong social mechanism constructed in the West has condensed information and limited expression to a space that is almost completely unimportant.

How do you feel about Xi Jinping’s re-election in October and what it means going forward?

Politics in China has never had fundamental change. It’s just that this year’s leadership made it seem more extreme. That means that a harsher authoritarian attitude was taken towards both inside and outside of the country, in terms of socio-economics, culture, and all kinds of antagonist activities. This will be a very dark period for human rights and freedom of expression. There will be harsher obstacles.

In your book you briefly describe a dream in which you find yourself running through an ancient village with your video camera—the more you film, the more danger you feel you are in, though in your dream you feel that you are the only one aware of the danger and therefore the only one equipped to expose it. Does the feeling from your dream extend into your reality?

Thank you for mentioning this detail. In fact, after I woke up, I realised that I was still living within the warning message of the dream. Our pursuit of truth can only tell us who we are and what kind of world we live in, but for the rest we are completely helpless.

You write affectionately of Allen Ginsberg. Do you have a favourite memory with him, or a valuable lesson he left with you?

Allen Ginsberg was an intellectual of the purest sense, and someone who fought for his freedom of writing and thinking throughout his whole life. This is my most valuable memory of him. Meanwhile, Allen’s experience and that of all intellectuals today made me realise that art and literature have been thoroughly marginalised and lost their stance and function in society.

When I watched Rohingya, I expected the narrative to focus on the trauma experienced by the Rohingya community—instead you quietly observe the relative peace and blissfully mundane everyday of their life in the sanctuary. Why did you decide to hone in on that aspect of the story as opposed to the conflict and trauma they had already experienced?

The thoughts behind Rohingya, Coronation, and Vivos, [stem from] the fact that despite our rage and reflection, we cannot stop these tragedies from happening. This is beyond what we can ethically and rationally accept. It happened in the past, it is happening in the present, and I think it will continue to happen in the future. As a documentarian, what interests me even more is when things happen, how people who live under these situations can meet their most basic and essential needs in life and find the logic and reasons for their survival, including happiness.

At the end of Cockroach, there’s a promise to continue the fight, and a song of unity in the form of the ‘Glory to Hong Kong’. In your everyday life, how do you maintain hope for eventual change, despite, more often than not, circumstances feeling as hopeless as ever?

This is a very good question. In fact, hope and despair always go hand in hand. With bigger hope comes bigger despair. What we need to understand is that life is not one-time consumption, but rather a process in which we need to continuously confirm the value of life and share the same hope with others.

Despair is always there too, of course.