Art & Photography, Confessions, Culture

The Writers’ Paris has had several golden ages of which the present moment is probably not one. The Edith Wharton Paris, the legendary Hemingway-Fitzgerald-Gertrude Stein era and the particularly populous post-World War Two period with George Plimpton’s Paris Review, novelist’s Irwin Shaw, James Jones, Peter Viertel, Clement Wood and many others.

There were great moments such as the liberated Paris of August 1944 when army counterintelligence agent J.D. Salinger sought out Hemingway at the small Ritz bar that later carried his name, looking for encouragement and advice from the great man – and actually getting it.

The best film version of that post-war era was James Ivory’s strangely neglected A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries based on James Jones’ daughter Kaylie’s novel about her Paris childhood, full of accurate and touching expat details.

The glamour version must be Peter Viertel’s colourful memoir Dangerous Friends about his time as a screenwriter in the entourages of Hemingway, director Anatole Litvak and John Huston, for whom love affairs and infatuations kept pace with or leapt ahead of their creative output, a perennial Paris danger.

That was certainly true for Viertel whose marriage to actress Virginia Lee Ray, undermined by the flirting and infidelities in their milieu, broke entirely when he caddishly ran off with the early supermodel, Bettina Graziani.

When Bettina later left him for Prince Aly Khan, John Huston tried to console him – but then added: “I’m going to tell you something you’re not going to like, kid. Aly Khan is one swell guy.” But the prince had also been paying attention to Huston’s much younger then-wife, Ricki Soma, Angelica Huston’s mother, and on Christmas day, Viertel received an urgent summons to Hustons’ house. Huston discovered the prince had given Ricki expensive jewellery and they had a brutal row, leaving Huston sad, humiliated and with a painful black eye. Viertel consoled Huston but couldn’t help adding: “John, you’re not going to like what I’m about to say… but Aly is really one swell guy.” Life in the fast lane was dangerous, though – the prince died in a car crash outside Paris in 1960 and Ricki Huston in one in Dijon, in 1969.

Viertel was one of the great survivors who ended up in a long and happy marriage with the actress, Deborah Kerr. His script work included The African Queen, The Sun Also Rises and Beat the Devil but he wrote at a time when novelists “slummed” writing scripts rather than, as now, when screenwriters risk wrecking their careers wasting time on a novel.

The Paris expatriates of Edith Wharton’s day were more cosmopolitan, their involvement in French society deeper, than most of those of recent decades. Wharton’s French literary mentor Paul Bourget described her “perfect Louis XIVth French” learned early in life. It was actually through the French literary salon of Countess Rosa de Fitz-James that she became friends with Henry James during his two years in Paris. James called her the “pendulum woman” for her frequent Atlantic crossings before she finally settled in Paris (she would make the crossing 66 times). The two principal men in her life, lawyer Walter Berry and journalist Morton Fullerton, were deeply implanted in Paris with significant public roles there, Berry a great friend of Marcel Proust and Fullerton chief foreign correspondent for The Times of London, finishing his career at Le Figaro.

Wharton remained loyal to the Paris she knew from her earlier years. When César Ritz opened his elegant hotel in the Place Vendôme in 1898 – with the restaurant under the direction of August Escoffier – it revolutionised Parisian entertainment with a new opulence. Proust started going out again, to enjoy its luxuries and Escoffier’s delicacies.

It was said that Paris society was divided into two camps, pro-Ritz and anti-Ritz – but that the anti-Ritz faction had only one member: Edith Wharton. The guests at her Rue de Grenelle dinner parties might have had to be content with austere fare rather than the oysters, Foie gras and champagne they could expect at the Ritz.

Wharton later moved to an estate, Pavillon Colombe, eleven miles north of Paris (the current street address is 3, rue Edith Wharton) which is where she invited Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald to tea in the summer of 1925 after Fitzgerald sent her a copy of his new novel, The Great Gatsby. Zelda begged off, fearing she would be made to feel provincial. Fitzgerald instead asked along his friend Teddy Chanler whose family knew Wharton. On the way, Fitzgerald fortified himself with drink, which perhaps made the non-Ritzian tea party seem even more tedious. To liven it up, standing by the mantle, he embarked on what he considered a humorous anecdote about an American couple who stayed at a Paris bordello thinking it was a hotel.

“But, Mr. Fitzgerald, you haven’t told us what they did in the bordello,” Wharton said, finding the story inadequate, only setting, no plot. The record she left in her diary was no more favourable: “To tea, Teddy Chanler and Scott Fitzgerald, the novelist – awful.”

Both Wharton and Fitzgerald left emotionally resonant traces of Paris in their best later works. The golden dome of the Invalides looms over the sad denouement of Wharton’s The Age of Innocence as widower Newland Archer imagines but does not pursue a reunion with Countess Ellen Olenska. In the Tender is the Night period Fitzgerald, Ring Lardner (portrayed as “Abe North”) and Hemingway all lived around the western edges of the Jardin de Luxembourg. Fitzgerald’s nostalgic story Babylon Revisited is partly set on Rue Palatine alongside the church of Saint-Sulpice.

Perhaps the saddest Paris exile – apart from Oscar Wilde – was Preston Sturges’ from 1953 to 1959. Under studio boss William LeBaron’s enlightened regime at Paramount Sturges had enjoyed perhaps the most brilliant run of any screenwriter or film director – which came a cropper in 1944 when the ex-songwriter Buddy DeSylva took over as studio boss, followed by a misbegotten partnership with Hollywood’s original black hole, Howard Hughes, and nearly as bad luck with a Darryl Zanuck in decline.

Like Edith Wharton, Sturges had the initial advantage of a cosmopolitan childhood and excellent French acquired in childhood. He considered France as his second land, and returning to America as a child, spoke English with a French accent. When he was two, Sturges’ mother had ditched his “good for nothing” father, Edmund C. Biden, and taken him to Paris where she became devoted best friends with the dancer Isadora Duncan. When in Paris, little Preston came down with pneumonia, Isadora’s mother prescribed that he be given a spoonful of champagne each hour – which did seem to work but Sturges never lost the taste for it.

Sewing machine fortune heir Paris Singer – so named for the city of his birth – was besotted with Isadora and financed her entourage’s travels, joined by Sturges and his mother. Singer later became Palm Beach, Florida’s brilliant developer, much of its persisting charm created in his era – and which would inspire Sturges’ later great film, Palm Beach Story.

The discouraging story of Sturges’ return to Paris in the 1950s is recounted in his son Tom Sturges and Nick Smedley’s recent book, Preston Sturges: The Last Years of Hollywood’s First Writer Director. But Sturges did get at least one film out of it, The French, They Are a Funny Race (1955), Jack Buchanan’s last film, as well as a small role in the Bob Hope film, Paris Holiday (1958). (Hope, one of Sturges’ early Hollywood collaborators, had him play a writer who has turned his back on comedy).

In recent decades, a great many screenwriters have chosen Paris to work on their scripts but the more permanent residents are few – for good reason. As an older American playwright told me when I first arrived in Paris in the late 90s – intending to “give it a year” but staying on – that pulling up stakes from one’s native land in mid-career is usually disastrous. Perhaps for Wes Anderson, a lifelong Francophile, it was more natural.

For me it was, in fact, fear and respect for the French language which finally led me to Paris, in the most roundabout of ways. In the winter of second year in college, when we were all in crises of some kind, a friend decided to do his junior abroad to study in France. This seemed like a good idea and it caught on, becoming a mini epidemic. For me, it would not be to study but “to write.” But why wait for the next semester? And why France in midwinter with a language that had frustrated me for nine years of classes, including a summer (1968) spent there to master it. Another acquaintance had just returned from a language course in Cuernavaca, Mexico – “the land of the eternal spring” – where I also had cousins. Spanish was reputedly easier to learn for a dolt like me. So I went, learned Spanish, wrote the script for a musical comedy and got my first professional article published about the political violence in Mexico City later portrayed in Alfonso Cuaron’s film, Roma.

Spanish ultimately led to Spain and work in the Spanish film industry. And in Spain the word was, why not Paris? Now “comfortable” in one foreign language, I was less intimidated by another. Whatever school French I had learned was of little use so, feeling prosperous, I started class at Berlitz in Paris. There only the “vous” form was taught. Less prosperous, I moved on to the Alliance Francaise where it’s all the “tu” form. Soon I knew both. Bases were covered. When asked whether I’m “comfortable” in French I have to say that while I’m comfortable, I doubt those listening are. My Mexican linguistic origins cannot be disguised. A French friend said it sounds like Zorro from the French-dubbed version of the old television series.

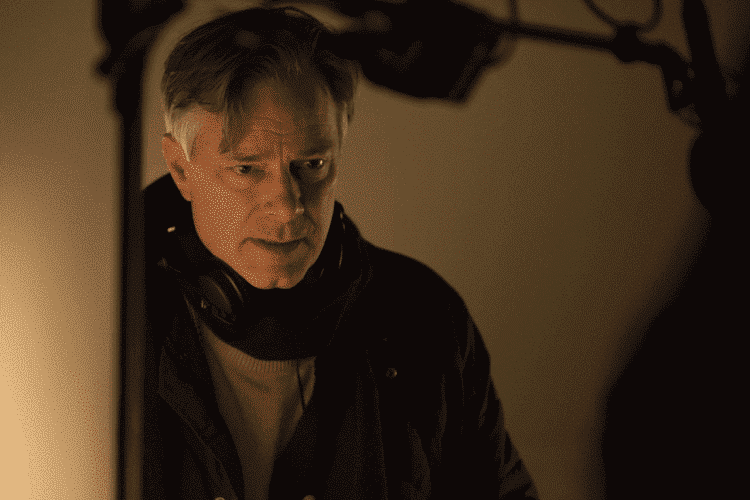

In 2014, I finally got to shoot in Paris, the pilot episode for an Amazon series, The Cosmopolitans. The production of Love & Friendship followed in 2016, though the shoot itself was in Ireland.

One can be productive or unproductive in all sorts of places. The old and probably best way was to isolate in some distant hotel as Kurosawa and his collaborators would do. The most useful work is not usually talking through stories or sitting at the keyboard. Walking is often the best way to think and Paris is the most beautiful, walkable big city. My favourite Paris activity is the same as that of the French novelist George Sand – “walking the streets of Paris dressed as a man.”

My second favourite Paris thing I first learned about aged nineteen in Mexico, was reading Hemingway’s account of his life in Paris attending the steeplechases at the Auteuil hippodrome. I recall thinking, if I ever live in Paris, I must do that. Whatever one thinks of his works, politics or persona, Hemingway was always right about places.