He was the model for possibly the most famous character in French cinema: Michel Poiccard in Jean-Paul Belmondo’s À Bout de Souffle. Beautiful and damned, just like Michel, Paul Gégauff was a nihilistic charmer with a roaring taste for infidelity, a cruel streak of misogyny, and a camel’s thirst for red wine and vintage Brandy. Although his life and career in cinema is now largely forgotten, he’s compared by friends both with Jay Gatsby – they share a glamour – and with Rolling Stone Brian Jones, found drowned beside his swimming pool, aged 27. There is indeed an echo of Jones about Gégauff’s obnoxious behaviour. He perished on Christmas Eve 1983 after being stabbed three times by his young wife. During an argument – reportedly over his attraction to her mother – he allegedly told her: ‘Kill me if you want, but stop bothering me.’

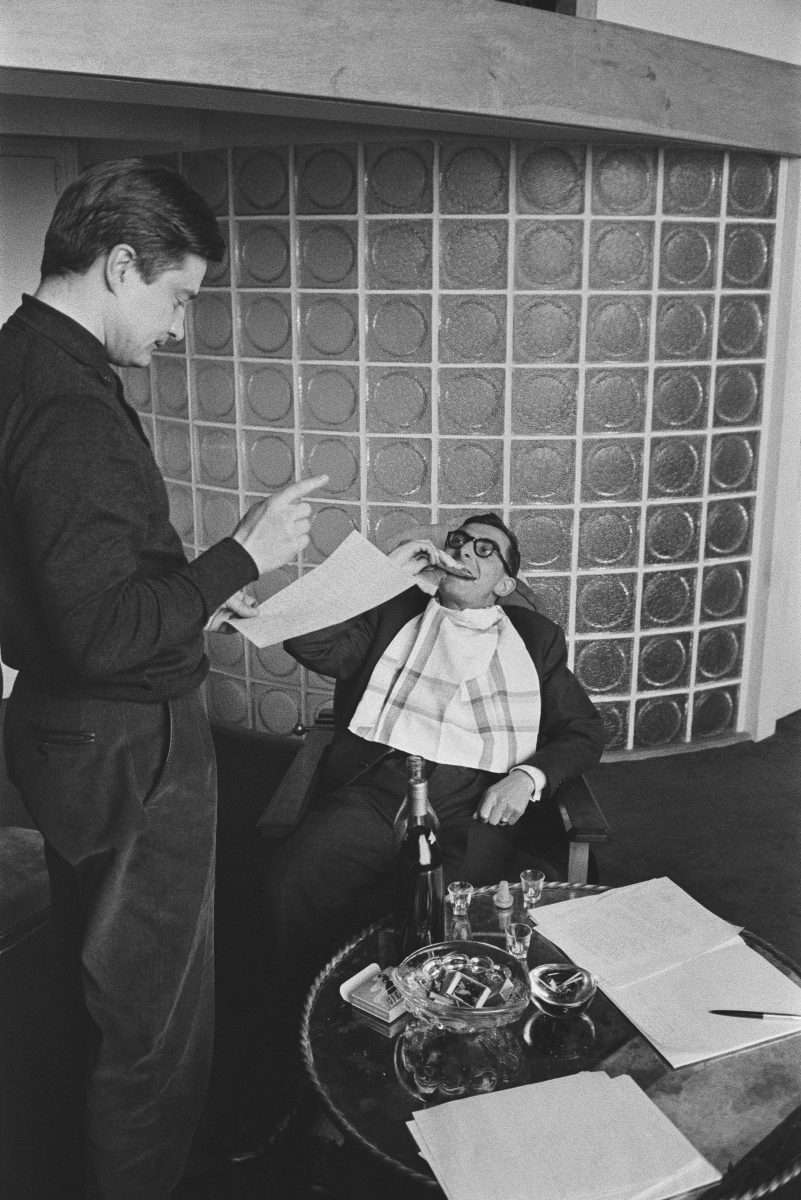

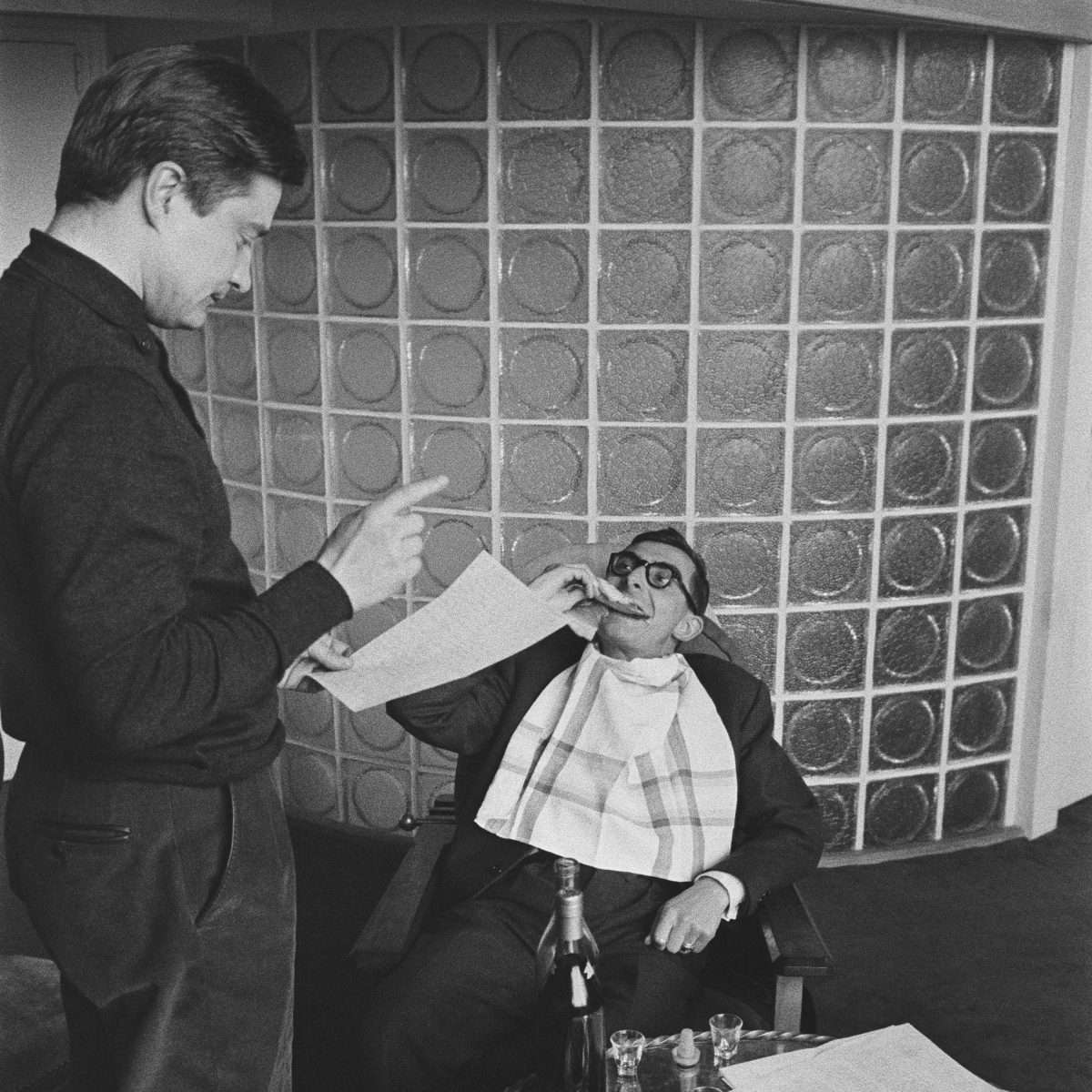

A successful novelist, Gégauff is probably best known for Plein soleil, his adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley which made Alain Delon a global star in 1960. He was also a frequent collaborator with New Wave director Claude Chabrol, writing 16 films for him in total, and appearing in projects including the sex comedy Une partie de plaisir opposite his then-estranged first wife. The 1975 film was an exploration of the breakdown of a marriage, with Gégauff playing the role of an abusive, faithless husband to a tee. No surprise, as he was no stranger to marital cruelty. His own biographer described Gégauff as an “alcoholic”, “sadistic”, and a “disgusting bastard.”

Gégauff was born in the border town of Blotzheim, Alsace, North Eastern France, on August 10 1922. It’s an austere area soaked in violence and conflict: a historically disputed area between Germany and France, the scene of devastating battles and related horrors including the Holocaust. His family had links to a textile business, and his grandfather was a successful captain of industry. But his father was a disillusioned gambler, so money was tight, and handsome, charismatic Gégauff was sure his future lay elsewhere.

He was 17 when the Battle of France started in June 1940, and the Blitzkrieg poured through his part of France. Young Gégauff was the perfect age to be conscripted into the Wehrmacht, as many young Frenchmen were. Instead, he escaped to the South of France. His biographer Arnaud Le Guern notes that he took a one way train to St Tropez “to save him from singing the Horst Wessel Lied in short pants with Uncle Adolf’s Hitlerjugend.” At 18, Gégauff wrote his first novel: Burlesque. Then, he moved to occupied Paris which was relatively safe and relaxed – an artistic hub.

Picasso, Edith Piaf, Jean-Paul Sartre Colette and others lived in the city, but it was also full of fascists. Burlesque had anti-Semitic overtones, and Gégauff’s friends at this time included Germans and far-Right French writers such as Robert Brasillach, who advocated for the Third Reich (Brasillac was executed in 1945). Le Guern said: “He dabbled in the black market. He went to Saint-Malo to buy meat that he smuggled back to Paris, blood oozing from his suitcase.” Whenever he was challenged by the German occupying force, Gégauff was able to reply in passable German. He came across as a streetwise dandy, rather than a Resistance fighter.

After the Liberation of Paris in August 1944, he studied law at the fabled Corpo-Assas, the Paris University law faculty where contemporaries included Jean-Marie Le Pen. Here he met Claude Chabrol, and the two men shared an apartment for a time. He wrote another novel, Les Mauvais Plaisants. Published in 1951 it was well received – the cynicism and humour struck a chord – but it didn’t pay.

There were a few minor acting roles and, although older than most of the New Wave, he fell in with that crowd. Gégauff, an endlessly antagonistic character, was said to be the inspiration for several cinematic anti-heroes. Most famously Michel, whose “indifference to human values” was noted by critic Pauline Kael, but also Pierre in Le Signe du Lion, Guillaume in La Carrière de Suzanne, Adrien in La Collectionneuse, Jérôme in Le Genou de Claire and Henri in Pauline à la Plage. Despite his influence, Gégauff feuded with the New Wave-ists, particularly François Truffaut. He mocked Truffaut, a cold and timid character whose Les Quatre Cent Coups in 1959 was the first acknowledged film of the genre. “You don’t exist François, you get excited, you get angry, you stamp your feet on the spot but you don’t exist,” Gégauff wrote in a letter to Truffaut.

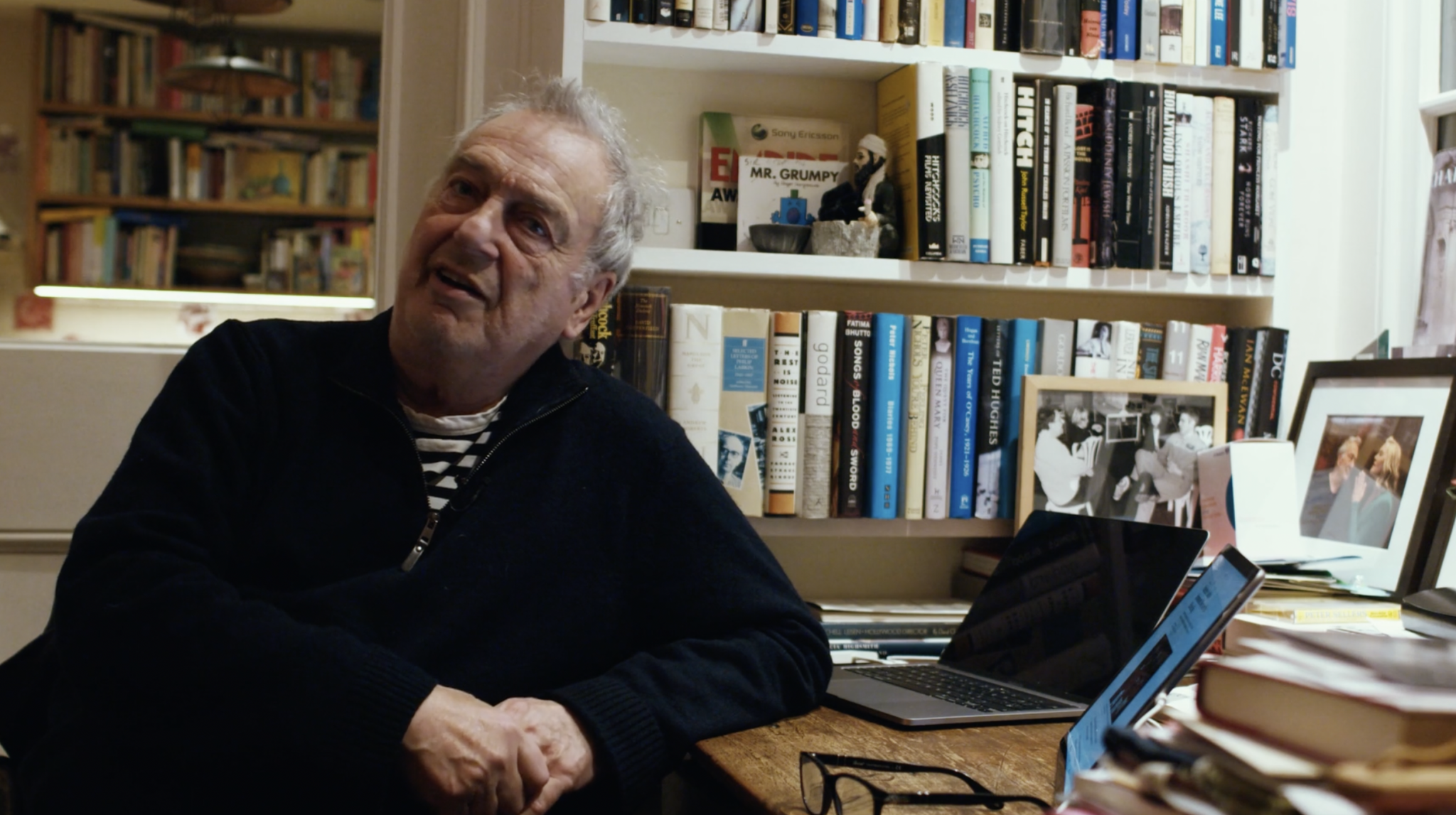

There was further conflict with Jean-Luc Godard. Gégauff sneered in a letter: “Jean-Luc was always in love with the stupidest shopgirls, he made them deliver flowers and chocolates when they dreamed of caresses.” He characterised directors Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette as sad old men: “excited by the plump calves of the little girls in skirts in the Jardin des Plantes.” In an interview Rohmer called Gégauff “provocative and paradoxical” but added: “I’d like to give him credit because personality had a strong influence on many of the films of certain of his friends: Godard, myself and Chabrol. He had a very strong personality.” And his script writing was also brilliant. He wrote for Claude Chabrol’s New Wave classics, Les Cousins and Les Bonnes Femmes, adding his own cynicism and cruelty. Chabrol once said of Gégauff: “When I want cruelty, I go off and look for Gégauff. Paul is very good at gingering things up… He can make a character look absolutely ridiculous and hateful in two seconds flat.”

Highlights included the line in the 1972 black comedy Doctor Popaul: “You only find moral beauty in ugly people, it’s one of the great paradoxes of humanity”. In an interview in 1968, Gégauff said: “I have never been interested in anything, I have never done anything, at least nothing worthwhile, before the cinema”. As the New Wave began to break up as a cultural force in the late 1970s, Gégauff became increasingly disillusioned, his drinking more problematic. His relationship with actress Danièle, whom he met in 1961 on the set of Les godelureaux de chabrol, was struggling, too. She left him for a film producer, but agreed to star in Une partie de plaisir.

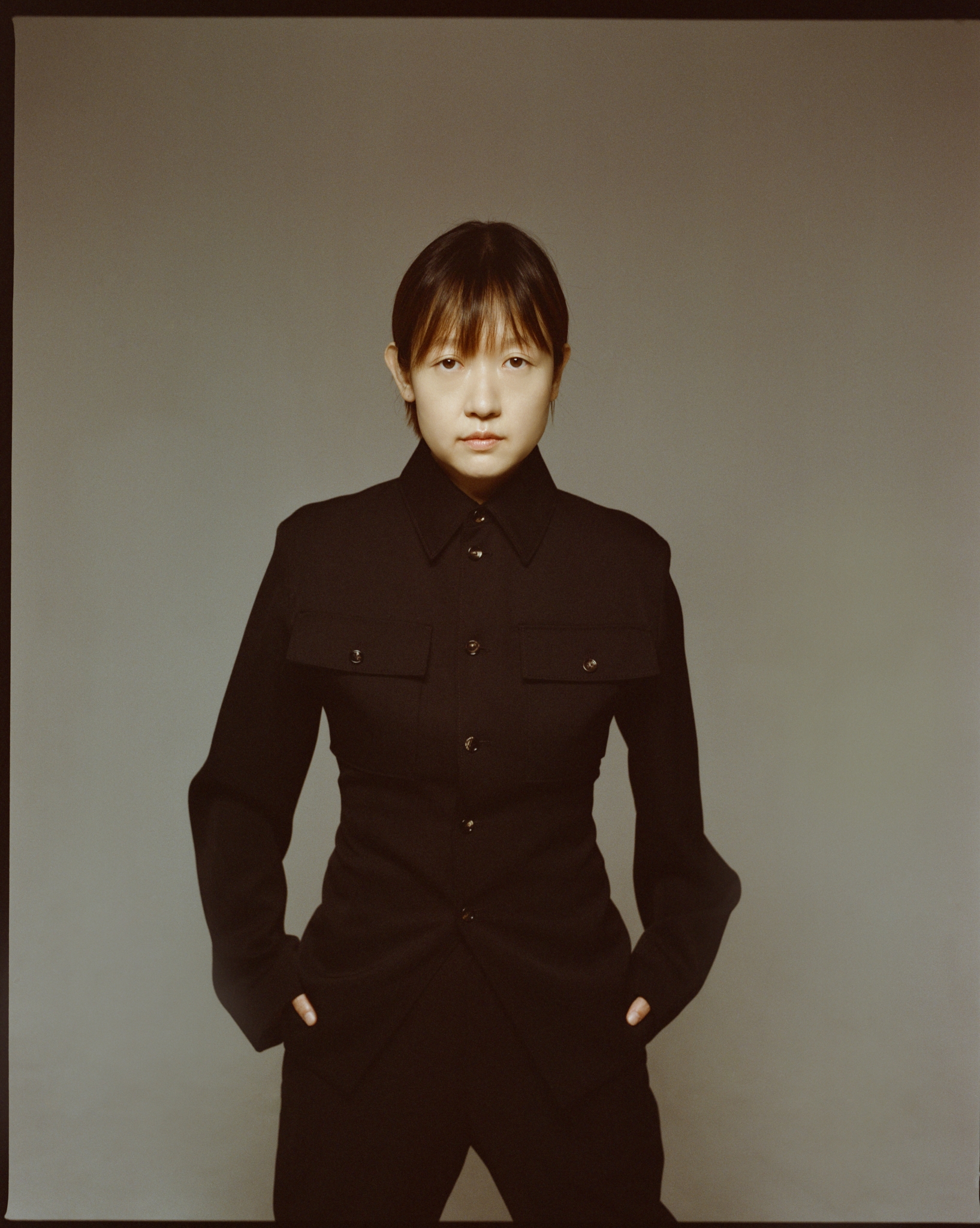

Released in 1975, it tells the story of the break up of a marriage after the husband has decided that he and his wife should take other lovers while also describing their sexual encounters to one other. The critics weren’t kind, with one in Positif saying that he looked “like a girl… like he’s just come out of the hairdressers.” More significantly, the experience of filming didn’t change Daniele’s mind about leaving him. Berenice de la Salle, married to Gégauff’s friend, Pierre, recalls that around this time he arrived at their mansion apartment on a moped, downed an entire bottle of Hennessy XO, and then urinated on the brand new carpet in their study – before weaving his way back home again. She called him a “poster boy for bad behaviour”, a womaniser and a misogynist and added that he thought women weren’t worth listening to. However, not everyone was so jaundiced about him. The actress Arielle Dombasle was a friend and she introduced him to aspiring actress Coco Ducados in 1979. Ducados was then only 20, the daughter of a Norwegian mother and father from Reunion. Initially Ducados told him: “You are too old and I am too young.”

That much is clear in a picture taken of the two of them that summer. She can be seen smiling shyly at his shoulder as they holiday with actress Josephine Chaplin, daughter of film icon Charlie, and her lover Maurice Ronet, who starred in Plein soleil. Despite the age gap, Gégauff and Ducados married. In the years which followed, Gégauff’s hedonistic drinking hardened into an alcoholic spiral. Christmas 1983 was spent in a cabin in Gjovik, outside Oslo. It was reported that they argued and he allegedly told his young wife: “I’m tired of being loved for myself, I would like to be loved for my money.” He was then stabbed three times by a kitchen knife after reportedly/allegedly telling her: “Kill me if you want, but stop bothering me.”

These days, Ducados still lives in Norway and now works as a screenwriter and dramatist. Gégauff’s best epitaph comes from long-time professional partner Claude Chabrol who said: “We all knew that Paul could not die peacefully. His dream was to end up assassinated. His violent end, between alcohol and argument, proved him right. This man shouldn’t – couldn’t – end up dying in his bed.”