In August 2013 I came back to Siena to shoot Palio, the apotheosis of my life as a documentary filmmaker. For months my crew and I woke up at 4.30 am, catching the dawn when the jockeys rode the crests of the Tuscan hills before plunging into the chaos of Siena on the days of the race. We’d face the intrigues of Siena’s rival factions, not to mention nervous producers who were doubtful of my choice of protagonists. But we won! The jockey I’d picked to follow out of the ten available emerged victorious in both Palios held that year, a fantastically rare achievement. No film crew had ever managed to follow a winner. The New York Times coined it “Rocky on Horseback,” and I was drunk on the landscapes and emotions I had captured for years to come.

The advantage which had enabled me to penetrate the closed world of the Palio jockeys was that, despite being an outsider, I spoke fluent Italian, and with a strong Tuscan accent. I was born in a farmhouse twenty miles from Siena, the last baby in the village to be delivered at home—by candlelight, as the energy board was on strike that night. The old men sitting outside the bottega would shout out at me in their crinkly voices every time they saw me, “Nata al lume di candela!” (Born by candlelight!) They admired the fact that my parents had shunned the modern hospital.

The village was small, 120 inhabitants, and our house was one kilometre away, surrounded by vineyards and woods. My parents had moved there from London in 1968. They have spent the last 55 years restoring the house. They’ve stuck to their hippy ideals: to grow a kitchen garden, make children and art. Throughout the decades, my mother painted the views from every window numerous times, while my father drew the reclining figures that lay about the pool all summer, and us daughters doing our homework in front of the fire all winter.

The winters were long and cold and school life in Siena was soul destroying, with authoritarian teachers whose aim in life was to prove you were useless. My sister and I would stare at the driveway in the afternoons longing for the arrival of a visitor with an exciting story to tell. My mother, reading Proust on the sofa, often declared that boredom was a divine state, a source of contemplation and creativity. Television, of course, was banned.

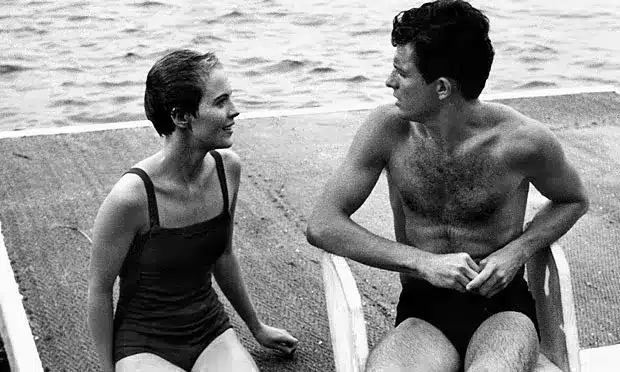

Then the summers came. Life at home in the seventies was a hard kibbutz by day and a continuous alcoholic party at night. Bruce Chatwin, known as Chatterbox, stayed occasionally, firing his unstoppable words at every meal, driving my mother bonkers. He called our house “Haute Boho.” He was forgiven by posing for her in his only quiet moments, when he wrote. I remember the big preparations around the time Lady Diana Cooper came for lunch. Born in 1892, she was a friend of my grandmother and a famous beauty of the last century. She appeared dressed head to toe in lilac. She snubbed our tomatoes and proceeded to drink the bottle of vodka and eat the box of chocolates she’d brought with her. Apparently this was her only form of nourishment.

My grandmother Mougouch caused many late nights and tearful mornings, as my mother couldn’t forgive her for not having prevented the suicide of her father, Arshile Gorky. The wine (made by my dad—undrinkable) made sure no wounds were left un-prodded. My sister and I would fall asleep to the sounds of shrieks of laughter or floods of tears, interrupted only by the crickets or the clanking dishes. One of the house rules is that however late or chaotic the party, the dishes must be washed before going to bed.

Bernardo Bertolucci and Clare Peploe were part of our extended family even then, as my mother had grown up with the Peploes. Clare’s mother was a painter and her grandfather was a famous sculptor, so our families shared a background. Bernardo’s father was a poet, so was my grandfather, and this was another overlap. Clare’s film-diary in Super 8 have her niece and I crawling bare-bottomed by the pool; and on the same reel, Bernardo directing Novecento. Which means I knew them before I could walk.

Life at home got a bit intense for me as a child. To escape, I’d hop on my bicycle and disappear to the village for hours a day. I had one good friend, the daughter of the cobbler who’d been set up by the local priest with a woman from Caserta. Daniela and I spent the afternoons building perfect little fires in the middle of the woods, playing ‘quattro cantoni’ in the tiny piazza with other kids or following the old strange wrinkly villagers. Once we secretly followed the seamstress’ father, who walked past us like a zombie carrying a dead rabbit by its ears. Daniela and I invented sinister stories about him as an evil killer. I felt guilty a week later when my dad insisted I go with him to a village wake, and lying on his bed, dressed in his finest, was that same old man of the dead rabbit. He’d never looked so neat and tidy, so stiff and waxen: he was hardly recognisable. He had a purple ribbon around his shiny black shoes “to stop his feet from flopping,” said my dad.

When I was eleven, the village lost its charm when Daniela stole an engraved pen knife my grandmother had given me. Daniela lied to me about where she’d got it and I took to my bed with a fever, changed schools, and never went back to play with her. There was no escaping the family house anymore. My older sister Saskia and I became friends, and together we formed an alliance that brought modernity into the house. Commercial “Mulino Bianco” biscuits appeared, then electrical cooking appliances such as a Magimix. In 1981, I finally read the ten books which were part of the deal and our first TV was bought.

When I was thirteen, my cousin Miranda Cowley Heller turned up with four friends in their early twenties who made adulthood seem irresistibly fun, especially outside Italy. I left for English boarding school, fed up with the gruelling Liceo Classico in Siena. After a couple of years our Tuscan house became my teenage girlfriends’ summer idyll, and many lost their virginity to the handsome Genoese boy who spent his summers up the road. Bernardo was inspired by such virginity-loss stories for his Stealing Beauty, and promptly took much of our furniture and my father’s sculptures to dress his nearby set.

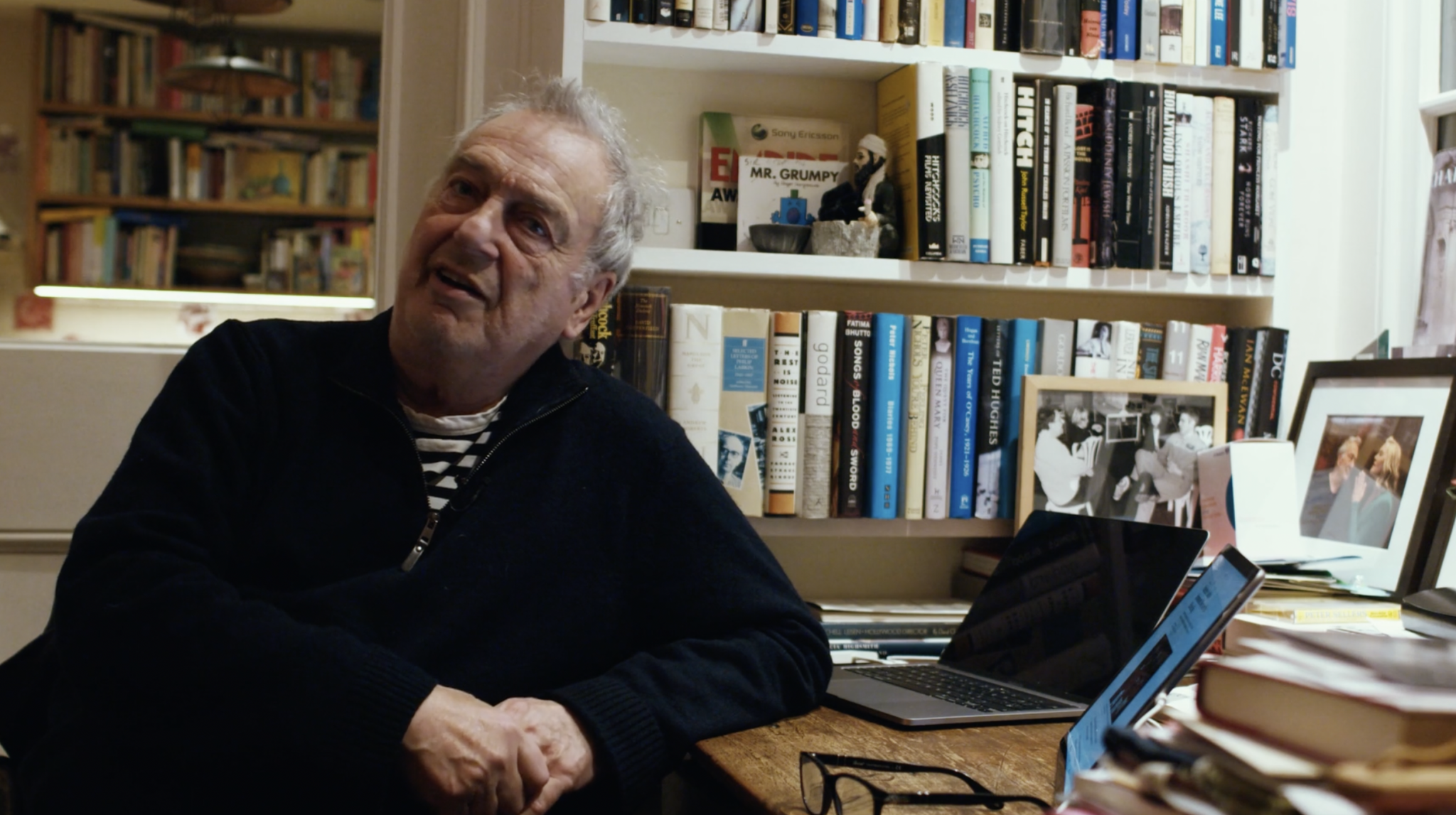

After boarding school, I went to SOAS for a history of art degree, followed by the National Film School. Bernardo and Clare used to stay with us a couple of times a year. One summer, he gave a series of screenings for me and some film school friends. As he never accepted offers to teach, this was an unusual privilege. We’d sit on the floor in his bedroom, he’d lie on the bed with a spliff and we looked at tapes of films chosen by him. Soy Cuba was one. Also The Lady in the Tutti Frutti Hat. What these films had in common were long uninterrupted shots showing imaginative camera movements. He showed us La Ronde, one of his favourites. Max Ophuls said that the camera should move “like the wind,” and this idea meant a lot to him. He said that in imagining a shot, he thought in terms of “melodrama” rather than other art forms, such as comedy or tragedy. His film La Luna—inspired by Clare’s mother—has the idea of melodrama incorporated in the plot.

At the end of these comfortable, low-keyed sessions he showed us Il Conformista. He hadn’t seen it since its release, and afterwards he left the house and sat by himself on the lawn in silence for over an hour. When he came back, he said this film had what very few films enjoy: luck. The right actors were free at the right time, the crew was happy, everything held together. It’s not always like that, he said.

At the time, I was keen on the spontaneity of documentaries as opposed to the contrived and controlled world of fiction, but Bernardo made us understand how important it was to keep spontaneity even in scripted shoots. Before and after university, I was a “traveller,” backpacking with my friends every summer in Laos, Thailand, Tibet and Cambodia, chasing ‘real’ adventures. In the most remote parts of the world, I found that my upbringing in the Tuscan village had prepared me to fit into any rural setting, while my bohemian family had made me appreciate artistic environments where the truth is spoken and shame is unknown.

After film school, I kept travelling to Africa and Central America making my documentaries, obsessed about ‘context’ and ‘point of view.’ Film school also led to a serious boyfriend, Valerio Bonelli, who was learning to become an editor. He passed the test of a summer in Tuscany by doing peacock dances and competing with my sister over who cooked the best Melanzane alla Parmigiana. Bernardo was there the night Valerio’s parents came to visit us for the first time. Their reputation as fervent communists preceded them, and Bernardo chose a menu with a red theme: gazpacho, followed by Bistecca alla Fiorentina.

Five years later, Valerio and I became parents. Our Tuscan house became a baby paradise for my sister and myself. With our own offspring, we revisited the wonders of the woods and the chicken coop and the pond. The house remains the pulsating heart of our growing family. Our children called it The Bubble, even before Covid.

To this day, the house remains a hub of activity as my mother scrubs and bosses her descendants. Delicacies have to be produced at every meal, with fresh produce grown in our earth. Lunch times are spent analysing the night before, with water clearing the mind and giving tremendous insight into everyone’s problems, which often go back at least three generations. Pieces of conversation are repeated, arranged in the larger scheme of the subjects’ lives and put in order like a mosaic.

Valerio and I have spent many summers editing in our Chianti bubble. Following Palio, a couple of years ago we were busy with Sanpa, Sins of the Saviour for Netflix. This summer we will be editing The Gymnasts, our first narrative series, which will launch Paramount Plus in Italy. Like an accordion, the house stretches to support us, our work and our children, who are now old enough to bring their own boyfriends and girlfriends. The house is the perfect setting for another generational round.