Director Gaby Dellal discusses Park Avenue, a story of mother-daughter miscommunication which, despite its Upper East Side setting, will be familiar to all.

Life imitates art for Gaby Dellal. Her latest feature film, Park Avenue, is the result of a series of fateful encounters and instances of happenstance. Dellal met the film’s would-be protagonist one day walking in Central Park. Kit, a former model, was a bon vivant who hated her family, had cancer and told no one. After Dellal decided to make a film about her, she found out that a beloved friend, who had died decades earlier, happened to also know Kit (well enough to have spent several Christmases at her Park Avenue home). As Dellal was finishing the film, she herself was diagnosed with cancer.

“You think you can say, ‘Are you scared of dying?’ but in fact you can’t. Even though I say whatever the fuck I want, I couldn’t,” she says.

Dellal is a filmmaker who has worn many hats. Raised in London, she spent a decade as an actor in the 1980s before moving across the aisle to direct several film shorts, including Football (2001) with Helena Bonham Carter. Since then, she has directed feature films Two Wheels Only (2003), On a Clear Day (2005), Angels Crest (2011) and 3 Generations (2015), as well as theatre productions such as Stitchers at Jermyn Street Theatre (2018) and Ava at Riverside Studios with Elizabeth McGovern (2022). As a “side thing,” Dellal also turns her hand to interior design—a skill that is apparent in the uptown chic interiors of Park Avenue. She was the sole architect of Sienna Miller’s internet-famous thatched cottage: “I wanted a Gaby house!”, the actress told Architectural Digest.

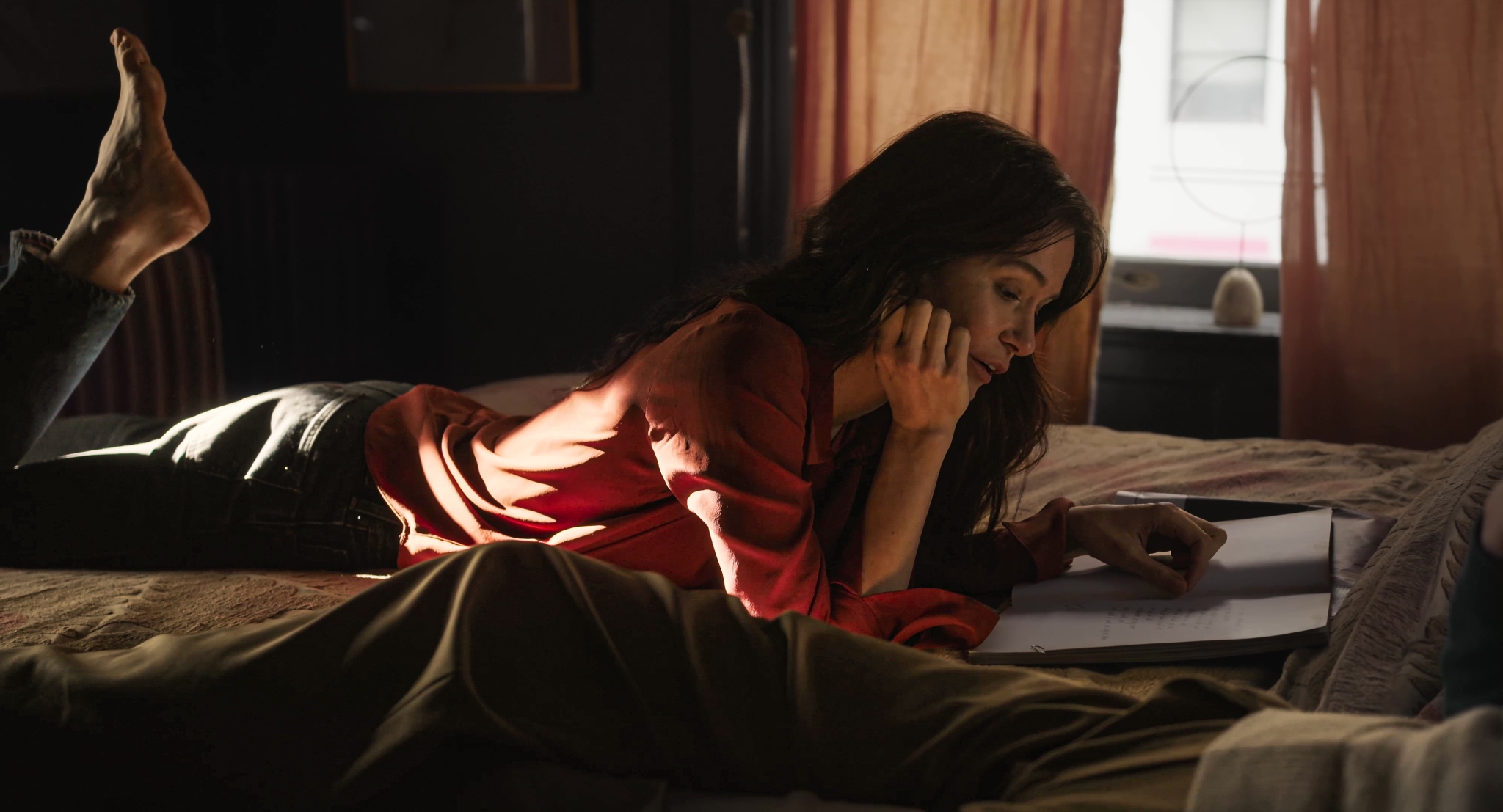

Fiona Shaw in Park Avenue. Credit: Spenzer-Pazer

In Park Avenue, the director reckons with the big questions, exploring the fallout of a hidden cancer diagnosis between mother and daughter. Kit (Fiona Shaw) and her daughter, Charlotte (Katherine Waterston), push and pull against each other over the course of this drama, both keeping secrets of their own: Charlotte has left her husband but knows her mother will disapprove; Kit doesn’t want anyone to know she has cancer. Charlotte’s return to the family’s Park Avenue home coincides with the last six weeks of Kit’s illness, supported only by her doorman, Anders (Chaske Spencer), who is also incidentally Charlotte’s lover.

Though set in the present day, the backdrop is decidedly Old New York, with doormen and board meetings led by grand dames. Shaw, as Kit, is the star of Park Avenue, a flamboyant renaissance woman who rules this surreal uptown world; she waltzes around in gold suits, gets drunk on whisky sours and reels off campy one-liners like “Step on it, boys!”

Dellal cycled over to Shoreditch House to sit down with A Rabbit’s Foot, discussing Fiona Shaw’s scene-stealing performance, family secrets, and how theatre inspires the rich visual worlds she creates.

Georgina Elliott: In your previous film, Three Generations, Susan Sarandon has a line about daughters turning into their mothers and having daughters who are just like them. Do you feel Park Avenue shares that thesis?

Gaby Dellal: In Three Generations, Naomi Watts was desperate to hug her mother all the time. And I kept saying, “I can’t have those schmalzy scenes. Hands off!” And I think that’s maybe my go-to; I’m quite cold.

In this film I explored a mother-daughter relationship from an older daughter’s point of view. It’s a dance between two people that hate each other, irritate each other and can’t give each other a hug at the beginning of the film. And then by the end, Charlotte holds her mother like a foetus on the bed. But she does the same thing with her own daughter when Lily says, “Mum, aren’t you going to give me a hug?” She can’t help herself; she’s as cold as her mum.

GE: But you complicate the idea in Park Avenue. The film ends with a different sentiment: inheritance is not inevitable, a daughter doesn’t necessarily make the same mistakes as her mother. Charlotte chooses to go and tell Lily everything.

GD: Yeah, tell your daughter the truth. When I was growing up, there was endless gaslighting. My mother believed one story, my father told her another. Nothing was straightforward. As a child, you are confused, but essentially you know the truth. You just feel it, and if it doesn’t corroborate with what you are being told, you think you are going mad.

Throughout my own life, I’ve kept secrets. I’m scared of the truth, if I’m honest. But children need the truth and receive it without judgement.

GE: Park Avenue does feel like a spiritual successor to Three Generations, though.

GD: That’s what my children always say, “Mum, you just made the same film again?!” Obviously, it’s another mother-daughter movie, but I didn’t realise I was doing that. Park Avenue started because they wouldn’t give me a doorman for Three Generations. I set it downtown, and they said there are no doormen downtown. I said to the producer, “In my next film there is going to be a doorman.” So Anders, Park Avenue’s doorman, was the hook. It’s about New York City.

GE: The New York in Park Avenue seems like a New York gone by.

GD: I wanted to do an homage, but it had to be the New York I grew up with, like in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. When I lived downtown, I would get on the subway and go to Central Park every day. I’d go, “Wow, this is like going along the Seine in Paris.” So I was very excited about creating this beautiful old uptown world where Kit lives.

GE: Kit is such an extraordinary character. Was she inspired by someone in particular?

GD: I think you write what you know. With Kit, it became very clear that I was channeling my own mum. My mother only wore Saint Laurent, and I found it excruciatingly embarrassing. She was very glamorous and very beautiful. If she were sitting here now, she would put on red lipstick and would never look in the mirror to do it. I was a tomboy, and we clashed.

My mother was the only person who could wear a gold suit in the daytime and get away with it. Fiona Shaw is the only person who can carry off a gold suit at the Doctor’s office, head held high, unflinching – dressed head-to-toe in Saint Laurent, receiving news that she “won’t make it until the holidays”. The yellow leather cape that Kit wears at the start of the film was inspired by an orange leather suit my mother often wore. It made me uncomfortable. It was only at the end of my mother’s life that I appreciated all her eccentricities. In part, this film is an honouring of my own mother, as well as Kit Gill, the lady I met in Central Park.

GE: What can you tell me about the woman you met in the park?

GD: It is an amazing story; I don’t believe in coincidences. But I’m walking in the park, and there was this woman, incredibly beautiful like Katharine Hepburn, and she had this long red coat that was a bit mucky. She was leaning against a tree screaming, “Don’t ever have chemotherapy. I feel like shit!” I looked at her and thought, “Wow, you’re amazing,” and I said, “Come and sit down. Can I help you?” I got her sitting down on the park bench, and then the sun came out and she calmed down. We sat and chatted, and I thought, “Oh, this woman’s fascinating. I love her.”

Over the course of our two year relationship I would meet Kit in the park, and I would sometimes record her—she had tons of amazing phrases, like “the models at Bonwit Teller are based on me,” as she says in the film. At the end she was clearly getting thinner and thinner; she said, “I hate my family, and I don’t want any of them to know.” That’s where the idea for the film came from.

On the set of Park Avenue. Credit: Spencer Pazer

GE: How did you choose the actor to fill those boots?

GD: It was a really tough decision. Having worked with greats like Susan Sarandon and Lesley Manville, I was over the moon when Fiona Shaw accepted the role. I loved the idea of not making Kit completely American but having that Irish ancestry. And she had to be biting. On the page, you could say Kit is a cruel woman. So you have to have that charm and ability that Fiona has, in order to get away with some of the things Kit says and does, in order to keep the audience gunning for you. In the end, Kit is beloved and that is down to Fiona.

GE: Did anything about Fiona Shaw’s performance surprise you?

GD: Oh, yeah. It’s very hard when you’re making a drama not to have people sobbing all day in every scene. We did 10 takes—and I never do 10 takes—of the scene where Kit goes downstairs to the lobby after finally telling her daughter the truth about her father’s death. I wanted her to cry silently, because in my head her real tears would come out when she tells her daughter to leave and says, “Don’t wake me,” and the daughter doesn’t. But on take four, Fiona stood there, staring out, and just sobbed. Her face looked really contorted and not attractive; she did it animally, gutturally so, she couldn’t stop. I thought, ‘Oh my god, you’ve given me a gift.’ Fiona had given me a gift. We then amended the emotional level of the next scene. Collaborating with a great actress becomes very exciting in moments like these.

Fiona Shaw in Park Avenue.

“My mother was the only person who would wear a gold suit in broad daylight. Fiona Shaw is the only person who can carry off a gold suit at the Doctor’s office, when she is told she only has months to live.”

Gaby Dellal

GE: How does the decade you spent as an actress in the 80s inform your approach to filmmaking?

GD: I didn’t act for very long, but consider myself an “actor’s director”. I also think I’m a women’s director, always mindful that the camera is flattering. I don’t think male directors necessarily have the woman’s best interests at heart.

I wanted to act because I thought I could stop being me for two hours in a play. Theatre is my first love; I go to three or four plays a week. So I have a theatricality. If I’m in the audience, I don’t want to think of any of my problems. Film, to me, also has to transport you into a special world. So I’m not making docs; I’m doing the opposite. I want to suspend belief.

Park Avenue, directed by Gaby Dellal (2025).

Anders, Park Avenue’s doorman, was the hook. It’s about New York City.

Gaby Dellal

GE: Park Avenue is such a sumptuous, visual film. Does your work as an interior designer come into play when you’re building the world?

GD: My world always has beautiful surroundings. I really care about the mise-en-scène and have a real love of interiors, which helps. I dream of the decoration and colour palette of the film; I always see it in my mind’s eye. When I started making short films, they were all like Amélie, very unnaturalistic. I don’t do social realism, like Andrea Arnold.

GE: What was on the moodboard?

GD: I found these pink and pale blue silk pyjamas, which allowed me to go for Kit’s red hair. I had an epiphany: black walls that would make her red hair and pink pyjamas stand out—I realised Kit was going to wear pyjamas at the end. I wanted her to glow instead of being this dreadful, miserable, dreary woman. And then when she gets to the hospital, and it becomes dowdy, she’s still wearing her beautiful pyjamas, she’s still wearing lipstick.

GE: That feels like an important theme in the film, dignity in the face of death.

GD: Hugely. When my mother was dying in hospital, she examined her hands; “Oh, look at those liver spots. I must get them removed.” Some women are vain, but it’s that vanity that keeps them alive.

Park Avenue is in cinemas from 14th November