Zoe Whitfield talks to costume designer Nancy Steiner about her collaborations with Sofia Coppola, why she thinks we romanticise girlhood, and having her work on The Virgin Suicides feature in the new exhibit GIRLS. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between by Elisa De Wyngaert.

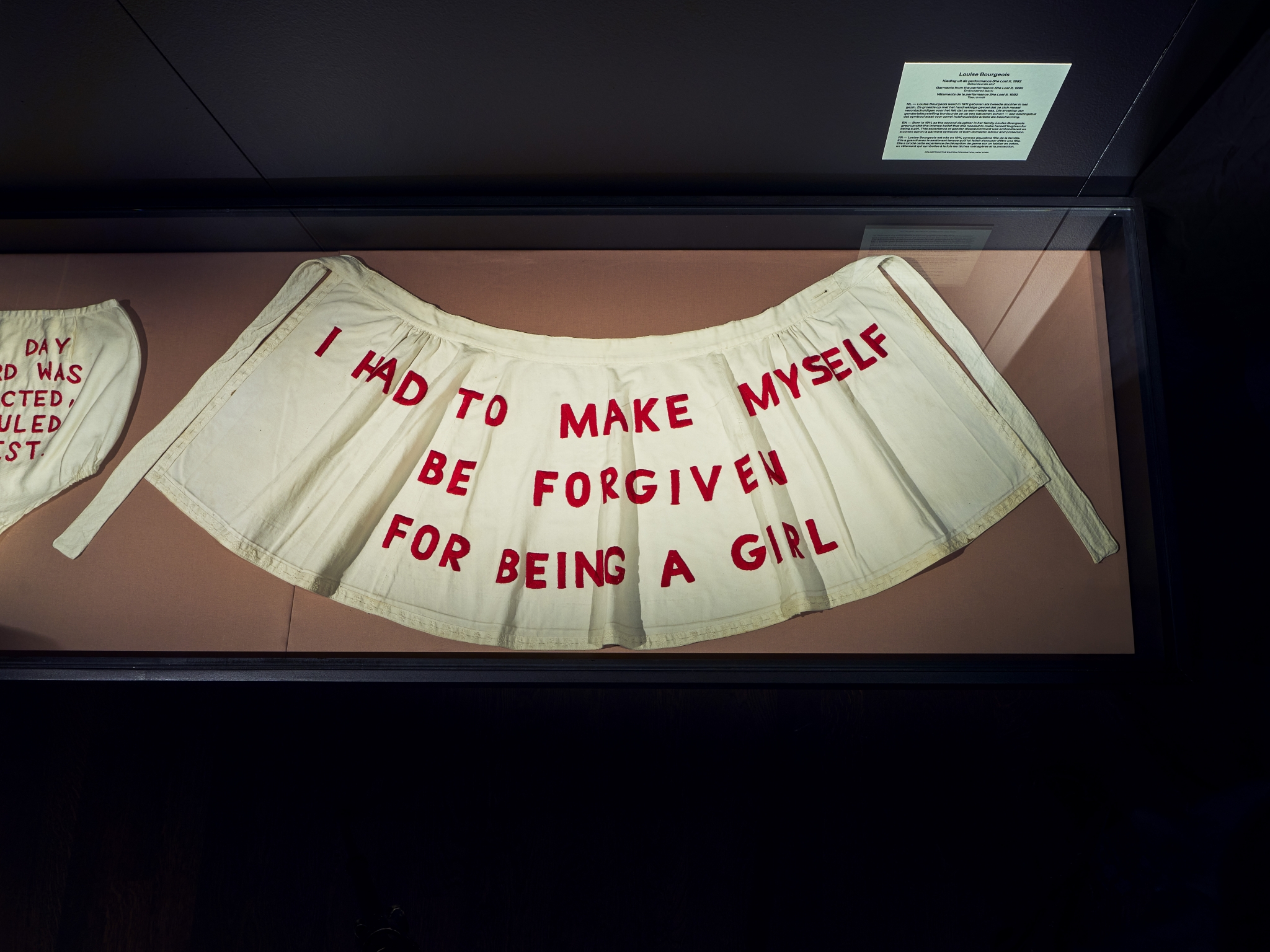

Years ago, while conducting research for her dissertation on the designer Helmut Lang, Elisa De Wyngaert was introduced to the work of Lucy Lippard, a writer, critic and activist who, during the 1970s, was a major proponent of using lived experiences and autobiographical materials to break down barriers between art and the audience. “All of a sudden I was allowed to tell those stories, to find connections,” shares the curator, reflecting on how Lippard subsequently shaped her approach to storytelling. In GIRLS. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between, currently on show at MoMu in Antwerp, this sentiment is employed several times over by participating artists, fashion designers, photographers and filmmakers.

A display of white frocks by Simone Rocha for example, appears in dialogue with a vitrine of accessories intended for one’s First Communion. Growing up in Ireland, the designer was enamoured by the outfits friends wore for theirs; unable to partake as a non-Catholic, her dresses would become a kind of response. Harley Weir meanwhile, with i love you as a friend, cuts and collages the familiar pastel pink notes of her youth. “Working on [previous MoMu show] Echo made me realise that so much is in memories,” continues De Wyngaert, “and many of those memories are based in teenage years, especially for girls. They speak about it and write about, and use it in their later work.”

The Lisbon sisters, of Jeffrey Eugenides’s 1993 novel The Virgin Suicides, never get the chance to turn their memories into art, instead their lives are commemorated across the page via the recollections of the boys who adored them from across the street. Reimagined for the screen by Sofia Coppola in 1999, it was costume designer Nancy Steiner’s own aesthetic past that informed the characters’ wardrobes: the flannel nightgowns the girls wear while protecting Cecilia’s favourite tree were made by Lanz of Salzburg, just like Steiner and her sister would receive every Christmas as kids. “She put so much of her own childhood and teenage years into it, because she grew up in the 70s,” offers De Wyngaert. “It’s not too on the nose, and I think that is what resonated with people watching it, that it felt so authentic.” At MoMu, a nightie worn by Kirsten Dunst and several other pieces are on display for the first time.

One of three ‘bedroom’ installations that establish the exhibition’s tone and interpretation of girlhood as a way of seeing, (additionally addressing its three core questions, about how girlhood has been represented, is remembered, and the idea of how ‘the girl’ shapes visual culture and fashion), partially concealed by translucent cream fabric is Lux’s floral prom dress. A near carbon copy of those worn by her sisters, (they’re described on the page as a “four-headed-creature”), the dresses were made by their mother, and in the film Coppola briefly puts us in the fabric shop. Hanging beside it at MoMu is Cecilia’s lace dress, the backstory of which is usually less explicit; Steiner says she imagined the youngest Lisbon rescuing their grandmother’s wedding gown from a box in the attic. Close-by, on a single bed dressed in era-appropriate pattern lies Lux’s bikini top, described on screen as, “a swimsuit that caused the knife sharpener to give her a 15-minute demonstration for free.”

“The room was a way to comment on boredom, a really heightened version of boredom,” notes De Wyngaert, (the second bedroom, designed by Jenny Fax, explores sleep, and the third, by Chopova Lowena, speaks to coming of age; wall text by adolescent psychiatrist Peter Adriaenssens accompanies all three). Other related objects appear later in the exhibition – books, DVDs – while it ends with the boys’ famous quote. “We felt the imprisonment of being a girl, the way it made your mind active and dreamy, and how you ended up knowing which colours went together…” “The layers of understanding [in the quote] inspired me a lot in this exhibition: it’s not one story about girls, but covering more the intricacies and the nuances of girlhood,” says De Wyngaert. “That is so strong in the film, that girlhood is not something that exists in a silo.”

Below, speaking to A Rabbit’s Foot via email from Los Angeles, Nancy Steiner discusses her collaboration with Sofia Coppola, why she thinks we romanticise girlhood, and watching Corinne Day at work on set.

Zoe Whitfield: Can you describe your own relationship with Girlhood and the questions raised by the exhibition – how has girlhood been represented, how is it remembered, and how does the idea of ‘the girl’ continue to shape visual culture and fashion?

Nancy Steiner: I haven’t been able to see the full exhibition – I only know the small part I was involved with – but as far as visual culture and fashion, I think we romanticise this period of life and equate it with innocence and femininity. Aesthetically we still think of the sweet shapes and silhouettes of girls’ fashions of the past; peter pan collars, full skirts, bows, ribbons, Mary Janes, etc are cemented into our conscious. But the reality is that girls started dressing like adults’ decades ago. I think the 1980s was when children’s clothing became mini versions of what adults’ wear.

ZW: The first ‘bedroom’ in the exhibition features several costumes from The Virgin Suicides; it’s the first time they’ve been publicly exhibited. What was your initial response when MoMu approached you?

NS: I was extremely flattered to be asked to collaborate. It’s always nice to be recognised for my work.

ZW: And how did you then decide which pieces should go on display – was there a specific criteria or was it more practical in terms of what was available?

NS: I’m fairly sure that it was based on availability, but that would be a question for Elisa.

ZW: Thinking about your introduction to The Virgin Suicides, were you already familiar with the book when you began working on the film?

NS: To be honest I hadn’t read the book when we made the film and I still haven’t finished it! This is a good reminder!

ZW: Can you recall some of your initial conversations with Sofia Coppola about the sisters’ costumes, and that collaboration more broadly?

NS: Thankfully Sofia has a very strong aesthetic and was clear about what she wanted. Knowing that I grew up in the 70s gave another layer to the costumes; it was in my blood and quite dear to me. Sofia didn’t want the loud, cliché 1970s for the film, she wanted the realistic version which is my favourite. We wanted each girl to have her own personality and for that to show in the way they dressed, but only in a subtle way. Mary was the oldest and the most mature, Lux coming into her sexuality, Bonnie was more girly and of course Cecilia, the depressed one, who found her grandmother’s 1920’s lace wedding dress in the attic and started wearing it constantly.

“I think we romanticise this period of life and equate it with innocence and femininity. Aesthetically we still think of the sweet shapes and silhouettes of girls’ fashions of the past; peter pan collars, full skirts, bows, ribbons, Mary Janes, etc are cemented into our conscious. But the reality is that girls started dressing like adults’ decades ago. I think the 1980s was when children’s clothing became mini versions of what adults’ wear.”

Nancy Steiner

ZW: And what did your wider research look like?

NS: I was already very familiar with this period as I grew up in the 1970s. Even though I grew up on the West Coast, the clothing was the same – I just went more preppy than skater/surfer. I started with my old yearbooks as well as photographers from that era, such as William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, and Joel Meyerowitz. I love doing research, it’s where you find all the details.

ZW: Inspired by Mary Ellen Mark’s photographs on the set of Apocalypse Now, Coppola had Corinne Day take photographs on the set of The Virgin Suicides, a number of which were published in a book by Mack earlier this year (which also features in the exhibition). Can you speak on that collaboration, and the significance of having the costumes documented in this way?

NS: I am so thrilled that Sofia was able to put these photos out into the world. Corinne was like a little elf, silently slipping between the crew to get her photographs. Her eye was so exceptional and it felt like she was the perfect person to express the feeling of the film.

ZW: Did you then, or do you now, have a favourite outfit from the film? Either in terms of a personal aesthetic, or a look that felt especially significant for the film or your process?

NS: I have to say, the prom dresses we made for the girls and the burgundy velvet suit that Trip wore were my favourites. I got to design and build them, and it’s always fun to design as opposed to buying or renting.

ZW: The film has obviously been hugely influential, as the new exhibition and the Mack book highlight. Can you speak on this legacy and the film’s impact?

NS: I am so proud to have been involved in making this film and having the costumes become so influential. I never imagined the mark it would make. This is still one of my favourite films to have worked on, not just because of the legacy it’s had. The experience of working with Sofia and all the young actors was so lovely, it felt like a family.

ZW: Building on that, I wondered how it feels to see the influence of the film’s costumes on contemporary fashion designers, photographers, artists and costume designers?

NS: To know that my work has influenced all these mediums has made my heart sing! I am grateful to be acknowledged for something that has become iconic and loved by so many.