In 2022, Andy Hazel flew from Australia to Indonesia to cover the filming of Ellis Park, a documentary from Justin Kurzel with Warren Ellis. What he discovered was a place of sanctuary and creative madness. Photography by Matthew Thorne.

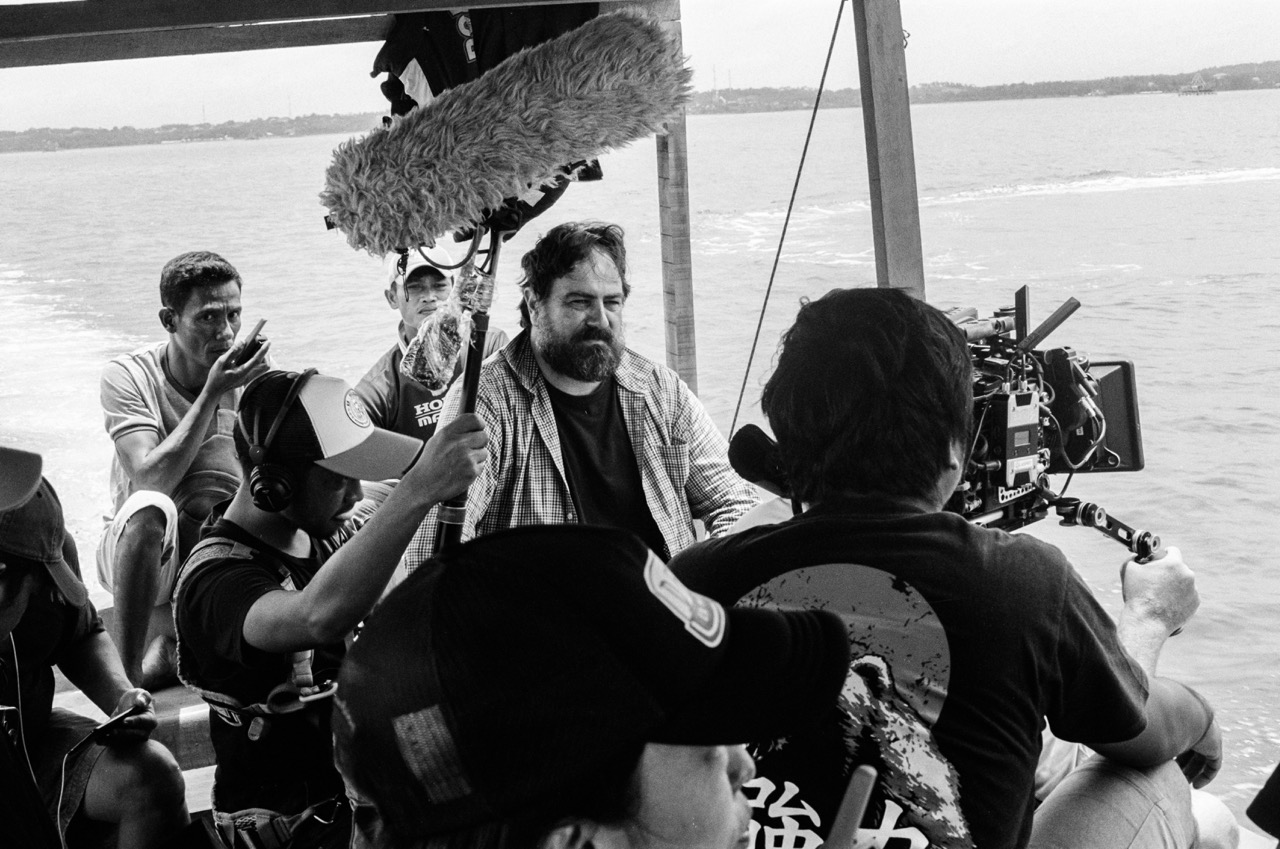

In 2022, I met director Justin Kurzel at the Marrakech International Film Festival. I was scheduled to interview him for 20 minutes but two hours and several beers later, we were still talking. Kurzel, best known for his films Snowtown, Macbeth, Nitram, and The True History of the Kelly Gang, moved to my hometown of Hobart, Tasmania, we shared a few mutual friends, and, like anyone who’s met him, he was warm, sincere, and generous with his time.

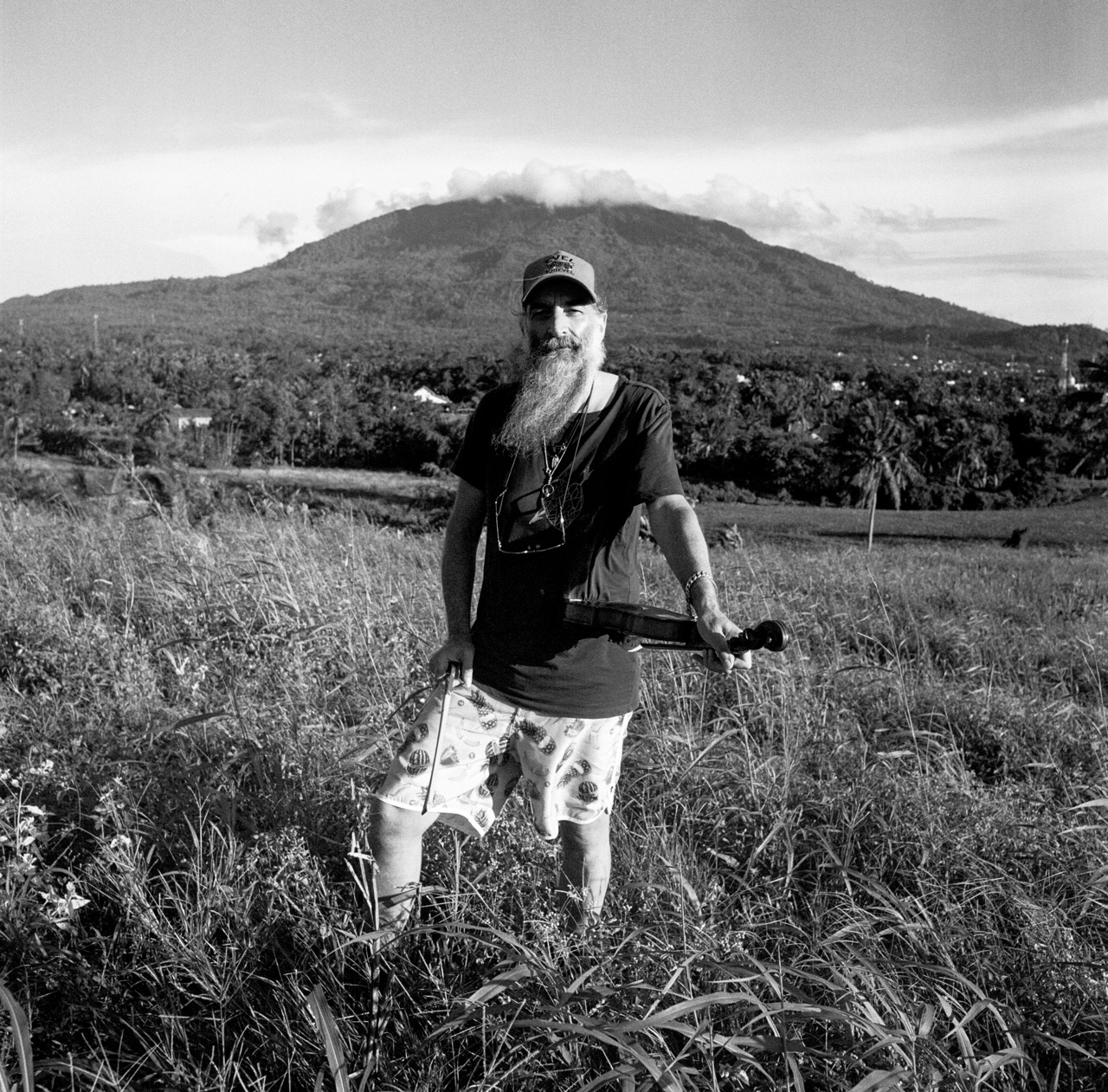

“I’m making a documentary about Warren Ellis,” he said. Of course, I knew Ellis, high-kicking violinist of the Dirty Three, Nick Cave’s right-hand man, and one of the most distinctive film composers working. “During lockdown he bought a wildlife sanctuary in Sumatra. It’s wild. You should come and do an article about it. A gonzo, fly-on-the-wall kind of thing.”I agreed.

Four months later, I turned up in the remote Indonesian village the film was using as a base. Kurzel was surprised. “I have no recollection of inviting you,” he said. “But I’m so glad you’re here.”

Producer Nick Batzias showed me some of the footage already shot for Ellis Park, the documentary named after the sanctuary: Ellis playing violin in the Australian goldrush town of Sovereign Hill, talking with his elderly parents, the rescue of hundreds of animals from a smuggling operation, their eyes reflecting the red-and-blue lights of police cars. This was going to be a remarkable film.

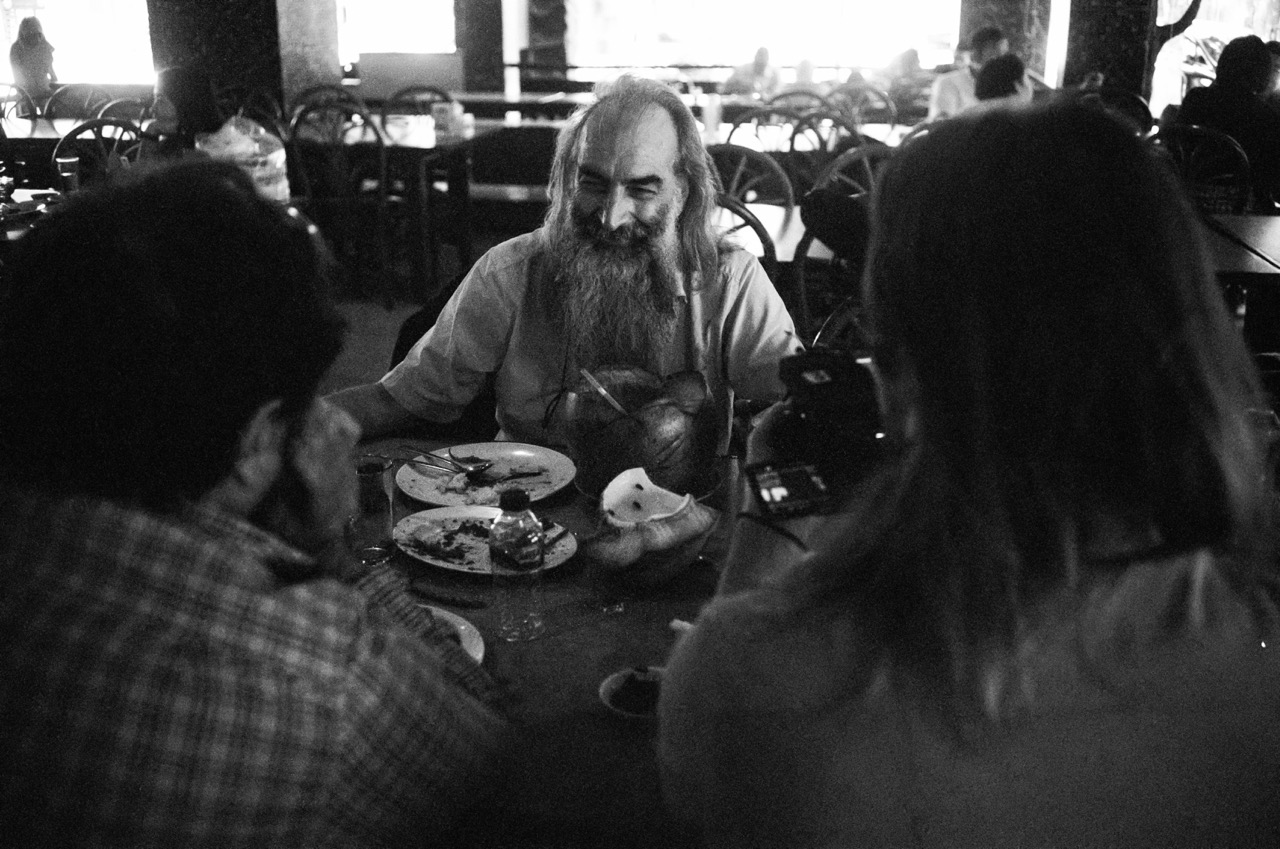

It is just after 7am at the Grand Elty Krakatoa hotel when I spot Ellis at the breakfast buffet. He is wearing thongs, Speedo brand shorts, and a faded blue T-shirt that says “Warren Ellis” above the year of his birth, “1965”, almost obscured by his grey and black beard. Ellis bypasses the papaya, honeydew, and watermelon juices to wrestle with an uncooperative urn of hot water as neatly dressed hotel staff watch on, politely attentive.

“D’ya reckon I could get a cup of tea?” Ellis asks. A young woman nods and disappears.

Ellis takes a seat beside Kurzel, leans back, hands behind his head, and listens. Next week, Kurzel will swap the Sumatran heat for wintry Canada, where he is directing the crime thriller The Order (2024). For now, he sits in the warm morning air, steadily putting cubes of fruit into his mouth, listening to Batzias outline his plans for a crucial sequence in their documentary.

“This is going to be the heart of the film,” he says, his trucker cap and tinted glasses framing his warmly expressive face. “When Warren meets Femke [den Haas].” He turns to Ellis. “We’ll film you and Femke, and keep the crew back. Do what you’d normally do.” Ellis smiles at the idea of normal. “We’ll have a camera way back to catch you coming into the park,” Batzias continues, throwing his hands up to indicate distance. “No phones. No social media. Anything that reduces the impact needs to go.”

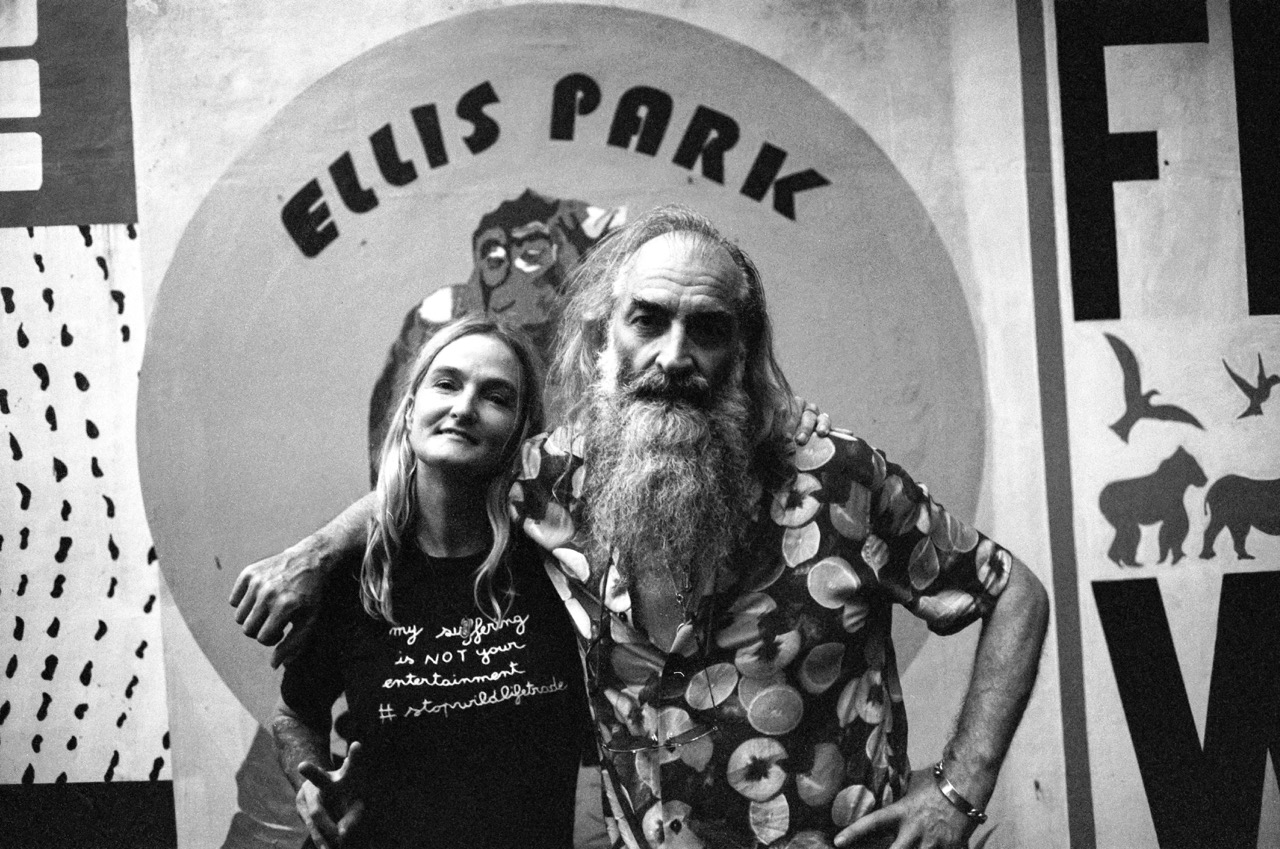

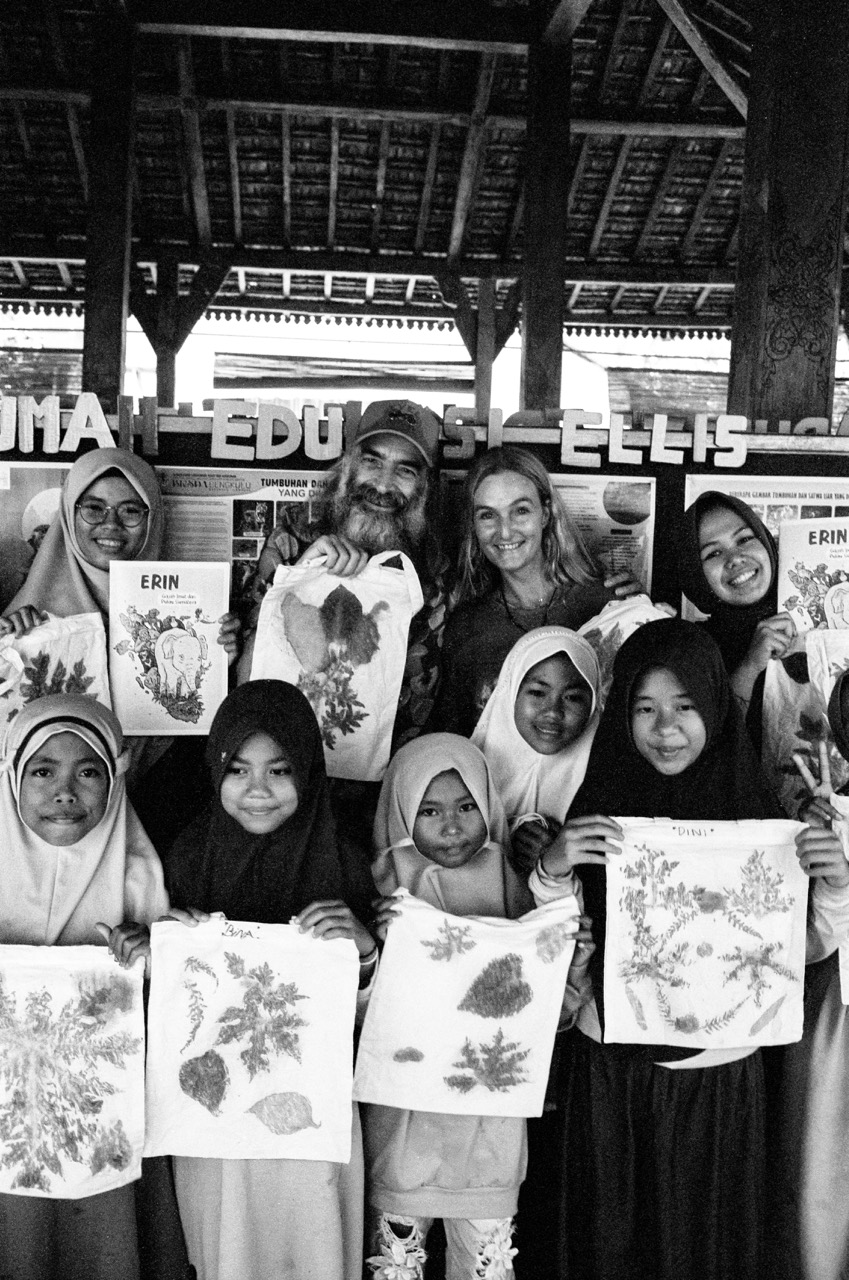

Ellis Park sits in southern Sumatra, not far from the coast, where the air is heavy and clouds loom low over the jungle and sea. The sanctuary was founded by Femke den Haas, a Dutch woman who has spent more than 15 years rescuing Indonesia’s most vulnerable wildlife: sun bears rescued from animal smugglers, former dancing monkeys, blind macaques, orphaned slow lorises, sea eagles with clipped wings—each with a story of mistreatment and survival.

Months before the Covid pandemic, Ellis reconnected with an old friend, Lorinda Jane. Once a booking agent for his band Dirty Three, Jane now works with the Jakarta Animal Action Network. When Covid arrived, Ellis retreated to his home in Paris, suddenly aware of the abundance of both money and time. He called Jane and she put him in touch with den Haas. Thirty seconds into a Zoom call, Ellis was all in. Within weeks, he had bought land for the sanctuary to expand. Months later, he crowd- funded the cost of the infrastructure—which, given Sumatra’s loosely regulated construction industry, rose as quickly as the rainforest itself.

“As soon as I saw Femke, as soon as I saw what she was doing, I never had any doubts about it,” Ellis says in the film. “I met two people who lived with her in a squat in Amsterdam and they said, ’It’s so great you’ve started the park up with her’. I said, ’I’ve never met her, what’s she like?’ ’When we were living with her, she was always bringing home stray dogs and cats and taking care of them. We always knew she would be doing something like this’.”

As the park grew, Ellis watched from his phone. He learned the names and faces of animals he hadn’t yet met, grew familiar with den Haas’s voice, her 10-year-old son, Rio, and the sound of the rainforest behind their calls. Today, for the first time, he will walk into it.

We arrive at the gates just after 8.30am. Sheds, cages, and small houses crowd together beneath the crosshatched fronds of barbel palms, broad-leaved banana plants, and cacao trees. The air is damp, filled with the shrill cries of unseen animals and the scent of citronella, an insect repellent that, it transpires, is much needed.

Beneath a magnolia tree, at a large wooden table, den Haas, blonde-haired and strong-jawed, sits calmly as a man with headphones attaches a microphone to her T-shirt. Her piercing aqua eyes sweep the scene with an easy, practiced vigilance.

“For a long time, the location was off the radar,” Ellis tells me later, over lemon and honey tea. “Not on a map. We had to get a security guard after the last raid because they confiscated about €150,000 worth of animals. The Chinese mafia is often involved in trafficking. Femke’s been shot at before. It can get pretty heavy.”

Near the bridge that leads into the park, the camera crew assembles, half-hidden beneath the shade of pandanus and bread-fruit trees. Beyond them, a shallow brown river trickles past, folding into the roots of the forest. Jane, who has flown in for the occasion, chats with the staff, pacing, smiling, shaking her head. “I can’t believe I’m here,” she says, almost to herself.

Cameraman Matthew Thorne rehearses the shot: the lift from tripod to shoulder, the steady glide across the bridge, the respectful distance he’ll hold as he follows Ellis and den Haas into the sanctuary. Around him, the air hums with insects, heavy with the rising heat.

Ellis’s memoir Nina Simone’s Gum: A Memoir of Things Lost and Found (2021) was sparked by a moment of impulsive devotion at London’s Royal Festival Hall. At Nick Cave’s Meltdown festival in 1999, Ellis leapt onstage after one of Simone’s final concerts to steal a piece of gum she’d stuck to her piano. He wrapped it in a towel, slipped it into a Tower Records bag, and left it alone for two decades. The book follows his attempt to memorialise the gum in sculpture, a journey that draws in a diverse cast of collaborators. “I’m moved by the idea of taking responsibility for others’ bad deeds,” he writes. Ellis Park is that impulse writ large.

“In animal conservation there is a lot of ’me, me, me’,” says Jane, standing by the gate of the park, dragging on a cigarette. “Some of Warren’s mates who are quite well known put money in and don’t expect recognition and we don’t promote that. What we do promote is the work. You can go through our Instagram and see the process. Eighteen months ago, this was vacant land.” She waves her hand behind her. “Now it’s buildings and cages and everything. You don’t need building permits here, so it’s just so incredibly fast. We also have a lot of freedom about decisions we get to make here. The board is very trusting in that way. It feels quite rogue. Warren likes that word, ’rogue’,” she laughs. “’Serendipity’, that’s another word he likes,” she says, turning her gaze toward the road that leads into Ellis Park, awaiting his arrival.

When you’re collaborating with some- body, you have to take risks. If you don’t take a risk, the end result’s not going to be interesting to anybody. Justin pushed me much further than I thought I was willing to go.

When you’re collaborating with some- body, you have to take risks. If you don’t take a risk, the end result’s not going to be interesting to anybody. Justin pushed me much further than I thought I was willing to go.

Warren Ellis

At 9.55am, word comes through that Ellis is nearly here. Action stations. We drain our cups of instant coffee and Batzias, just as he envisioned over breakfast, stands behind Thorne, their gazes fixed on the small monitor. As we spy him, the camera lifts off the tripod and onto Thorne’s shoulder in one smooth movement. Batzias watches closely. I ask him how he thinks Ellis is feeling.

“Excited more than nervous.”

As he approaches, resplendent in glittering bling and a fresh shirt emblazoned with pictures of fruit, den Haas comes out to meet him, radiating joy. “Fucking hell,” says Ellis, dark sunglasses hiding tears. They embrace. Den Haas’s 10-year-old son Rio crowds in for a hug too. A camera circles them, another watches from the trees where some members of the staff join Ellis in shedding tears. The man who makes it possible.

“Until Justin decided to do this documentary, I didn’t feel the need to come look at the land,” Ellis tells me later that evening. “I just saw photos and videos. I really liked the fact that any money donated—100 percent of it— went to the cause. I liked the fact that it was a real rogue setup and that it was driven by these people that just seemed extraordinary.” As soon as Covid permitted, Ellis was back to his cycle of touring, scoring, and recording with Cave. At the 2021 Cannes Film Festival, Ellis, who was there with Marie Amiguet and Vincent Munier’s The Velvet Queen (2021), which he scored, met Kurzel and Batzias, who were in competition with Nitram.

“Justin said, ’What have you been up to?’ And I said, ’Well, I did a record with Nick [Cave] and a record with Marianne Faithfull and wrote a book and opened an animal sanctuary.’ He’s like, ’You what?’ I said, ’Yeah, I opened an animal sanctuary.’ He just looked at me kind of dumbfounded. And I said, ’Yeah, I’m gonna get a big two-metre piece of the chew- ing gum made in marble. Sail it over from Italy on a, you know, big, big boat. Like, not sail it myself, but get one of those delivery boats and accompany it. I’m going to take it down the river—because there’s a river outside the sanctuary—and stick it in the park.’ And Justin goes, ’I want to make that film.’ And Nick goes, ’I want to produce it.’ And I didn’t think any more of it. Later that evening I got a text from Justin, and he just said, ’I’m serious, mate.’ About a month later he sent me a treatment and here we are.” Plans also included an unveiling ceremony for the gum statue that was to include performances from Michael Stipe and Flea.

Ellis Park is not that film.

“It was always about what inspired Warren, and how he responded to it,” Batzias agrees. “And the more time he spent here, the more it became clear: it wasn’t about the gum.” While shooting in Ballarat, Ellis decided he wanted to be baptised in the river that flows past the park. He discussed it with Kurzel and Batzias who went back and forth on the idea. Questioning whether it was possible, the local production coordinator Yournes Sari found an English-speaking Indonesian minister who could be there the next day at 1pm—a feat of production wizardry that briefly revived the plan. Ultimately, like the gum ceremony, it didn’t feel right. “And anyway,” says Batzias, “it would never have worked.” The river only runs during monsoon season, “and that’s not for another six months.”

Back at the park, Ellis is thirsty. “Are we going to put the kettle on?” he asks. “Can we pause for a cup of tea?” A man in a blue shirt nods and disappears. We are walking to the crest of the lightly forested hill behind it, toward the sound of a nearby mosque at prayer time. We’re now on “Warren’s land”, a large swathe of forested hills that Ellis recently bought to allow the park to expand. Later, he explains: “I had always said no to doing advertisements. But then I realised I could do an ad for, I don’t know, a French shoe company, and the money from that could go straight here. It could turn into something real.”

Ellis sits on the crest of the hill with den Haas and Rio, who gestures toward Krakatoa, the famously volcanic island on the horizon that Rio tells us, “has been pretty active lately”. The light has turned a rich, cinematic gold. Kurzel, watching from a distance, makes sure the scene is captured before quietly stepping into frame where he settles by Ellis to plan the next sequence. All around us, dozens of small holes puncture the ground.

Batzias catches my glance. “Fruit trees,” he says. “We’ll get Warren to plant some tomorrow. Hopefully he’ll feel like playing some music too.” For now, Ellis sits, the bay stretching below him, the forest humming at his back. Later that evening, I ask him what he had been thinking about. “The park,” he says simply. “What I love about this project is that the people involved just get on with it. They’re taking responsibility for things they didn’t cause, for someone else’s mess, and doing the heavy lifting anyway. That’s far more meaningful to me than sitting back and saying, ’It’s all fucked.’ It seems to me this is how things have to change now, through community movements. You’ve got to take things into your own hands. Embrace the serendipity.”

The heart of Ellis Park beats through three men: Batzias, Kurzel, and Ellis. Watching them negotiate what the film is in real time is a thrilling experience. Each melds their talents to create something bigger. Each personality is strong, yet everyone is working to accommodate what inspires Ellis. Batzias is chatty, quick with ideas, always tuned to the quiet needs around him. He’s usually on point, chatting with the park’s staff and the local film crew, always across logistics, anticipating disruptions, and open to suggestions.

Kurzel is a quieter, steadier presence, at least one eye always on the monitor where he seems to draw emotional threads tighter without seeming to pull at all. Away from it, much of his communication is with Ellis, Batzias, and cinematographer Germain McMicking. Best known for his galvanising portraits of damaged masculinity, Kurzel’s decision to turn his camera on Ellis, with all his fugitive spirit and emotional openness, is an unexpected one. Ellis Park will be his first documentary. A year after production wrapped, Kurzel and Ellis sat together at a Q&A during the Melbourne Inter- national Film Festival and spoke about it.

“Usually, you go into a film with very, very strong ideas,” said Kurzel. “I realised quickly with this that it just wasn’t going to be that way. We had to allow the animals, the people, and Warren to just sort of organically flow into the story.”

Ellis nodded, grinning. “It’s very hard to be organic when you’ve got a camera pointed in your fucking face all the time,” he said. “But Justin wisely said, ’Look, you’re at a turning point in your life, you need to follow this through.’ When you’re collaborating with some- body, you have to take risks. If you don’t take a risk, the end result’s not going to be interesting to anybody. Justin pushed me much further than I thought I was willing to go.”

Kurzel leaned forward slightly. “I felt an enormous responsibility,” he said. “Especially when I got to the park and saw what Femke was doing. What I was most surprised by was the act of creating. There are paintings every- where, there’s this enormous creative energy. A huge part of the conversation with Warren was about the act of creation. The soundtrack of the film was being written while we were filming, and it felt like it was coming from Warren and the park itself. Creation is ultimately what Warren is all about. The music, the book, the park. Everything.”

What I love about this project is that the people involved just get on with it. That’s far more meaningful to me than sitting back and saying, ’It’s all fucked’

What I love about this project is that the people involved just get on with it. That’s far more meaningful to me than sitting back and saying, ’It’s all fucked’

Warren Ellis

A breeze stirs, and overhead the low grey clouds slowly lose their battle with gravity. Rain is coming. Batzias chats with the local production crew as Ellis lowers himself onto a log beneath the canopy of a nikau palm and a goldfinger banana tree. He sighs, smiles and tries again. “D’ya reckon I could get a cup of tea?” he asks to no one in particular. Kurzel, anticipating the request, hands over a fresh brew.

“Did you make this with your bare hands, Justin?” Ellis asks, surprised.

“Yep,” Kurzel says.

Ellis takes a sip, eyes lighting up. “It’s pretty good,” he grins.

Thirst slaked, Ellis asks den Haas, “For the animals that can be released, how do you know when they’re ready?”

“When they ignore us.” she replies.

Ellis has already developed affection for many of the animals here through watching videos and following the park’s social media. Few residents have been filmed as frequently as Koja, a 25-year-old pig-tailed macaque whose spine became deformed after spending over 20 of those years inside a tiny cage. As we arrive, Koja bounds over to meet us. In his joy at meeting her, Ellis reciprocates her energy.

“Koja!” he cries.

“When we found her, she was skinny, sitting on top of a pile of plastic rubbish,” says den Haas, slipping on a face mask and opening the cage. “She was very trusting from the beginning, as if she knew she was being rescued.”

Ellis watches Koja eat crickets and passes on greetings from the staff at Ellis’s office back in London, also familiar with her from vid- eos. “There is something really wise about her,” he says, easing into her calm sense of focus. Since that traumatic time in confinement, den Haas says, “everything makes her happy now”. The park’s mascot, a monkey called Rina, carries her own story of survival. She was found in 2018, chained to a pole in the backroom of an animal smuggler’s apartment. The metal had torn into her skin, leaving wounds so deep they festered. Her captor, in a misguided attempt at care, doused them with gasoline. In her agony, Rina nearly chewed through her own limbs. Both arms were amputated after her rescue. Today, she plays a maternal role for the newest primates in the park, and her silhouette is its emblem.

Before they meet Rina, den Haas and Ellis take some food in the form of crickets wrapped in banana leaves. Part of the ritual of feeding animals here is to make each meal a game, den Haas explains. Batzias has visions of Ellis playing violin to Rina, a “music soothes the beast” kind of thing. Kurzel will settle for bonding.

“Bonding?” says Ellis, with a grin. “What does that mean? You can’t put your faith in God all the time. You have to tell me what to do. Would you like me to smother myself in banana juice?”

“Is that possible?” Kurzel asks, picking up Ellis’s grin and passing it to Batzias.

“You want me to read the room?” Ellis continues. “I’ve been unable to read the room for 58 years!” At that moment, Rio clam- bers down from a tree and hands Ellis what turns out to be “the best passionfruit I’ve ever had in my life”.

Den Haas leads Ellis into Rina’s cage, McMick- ing follows and makes himself invisible. Ellis hands Rina the banana leaf package, which she grabs with a foot. Ellis watches with a mix of love and fascination.

“Does she remember everything?” he asks.

“I think she put it in her past,” replies den Haas. “She’s not aggressive to people. And we give her a lot of extra attention because she needs it, and she deserves it, after living for so many years in isolation and in so much pain. If she could go back to living in the wild, it would be a very different relationship, but she can’t. It’s not just healing—physically treating the wounds—it’s a mental process as well.”

Den Haas edges forward, speaking softly. Rina darts toward her, then veers away from Ellis.

“It’s incredible how agile she is,” says den Haas.

“It’s amazing how different she is to Koja,” says Ellis.

“We might want to get some more interaction between her and Warren,” Kurzel murmurs. Ellis steps closer. Rina freezes.

“She gets so jealous,” says den Haas, inching forward again. Unlike Ellis, Rina stays still, reading the room.

Suddenly, she leaps backward and upward to the roof, and begins to growl, low and uncertain, then loud and very sure of herself.

With a sudden jolt, Rina lunges from the floor and strikes, tearing through den Haas’s trousers with a swift, purposeful bite. Den Haas barely flinches. She lifts Rina gently but firmly by the neck and holds her carefully under her knee. Blood trickles down her leg. “So, Rina has chosen Warren,” she says, with the measure of a schoolteacher. “And I am now seen as a threat.”

After a few minutes, Ellis re-enters, this time with McMicking and den Haas’s husband, “animal whisperer” Dano, whose presence set- tles the air. With the new dynamic, Rina calms and within minutes she and Ellis share each other’s space, until Kurzel calls cut.

We leave Rina’s cage, the sky darkens, and we’re told we have only a few minutes until the clouds will open. Quickly, we’re ushered toward the park’s office buildings as a deluge crashes over us with impressive volume. We huddle in doorways and grin at each other until the rain stops. Batzias calls a wrap on the day’s shoot, and we return to our hotel along muddy roads.

The morning after, the sky is a bright blue dome. Just east of the main office lies a path leading to the education centre. As we approach, we hear the chaotic hammering of children pressing plants. On either side of the path, young saplings rise from the soil, some marked with a small sign of the person who funded it, or to whom it was dedicated: Annie Proulx. Kurt Cobain. Mick Rock.

Ellis, striding past, spots a noticeboard outside the centre. It shows a photo of him and a short bio. He stops to read it:

“Warren Ellis, born 14 February 1965, is an Australian musician and composer. He is a member of the rock groups Dirty Three and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Warren Ellis is an amazing musician and cares deeply about nature and animal protection. To truly contribute to the protection of animals and nature, and to tackle the suffering of animals, Warren wanted to do something tangible. In 2021, Warren launched a much needed wildlife sanctuary named Ellis Park together with Lorinda Jane and Femke den Haas.”

“Fuck,” he says, sighing. “That’s actually really moving.”