Whilst more readily associated with cooler climes of Nova Scotia, the 20th century poet Elizabeth Bishop also cannily conjures the distracted attentions of a long hot summer day, says Carolina Julius.

Summer has its own state of mind. It is a season of drift. Attention flutters between books, pages, and thoughts—unable to settle in the heat, or the thrill of free time. It is a restlessness that frustrates and delights—this year, I have watched it unfold on the page in the poetry of Elizabeth Bishop.

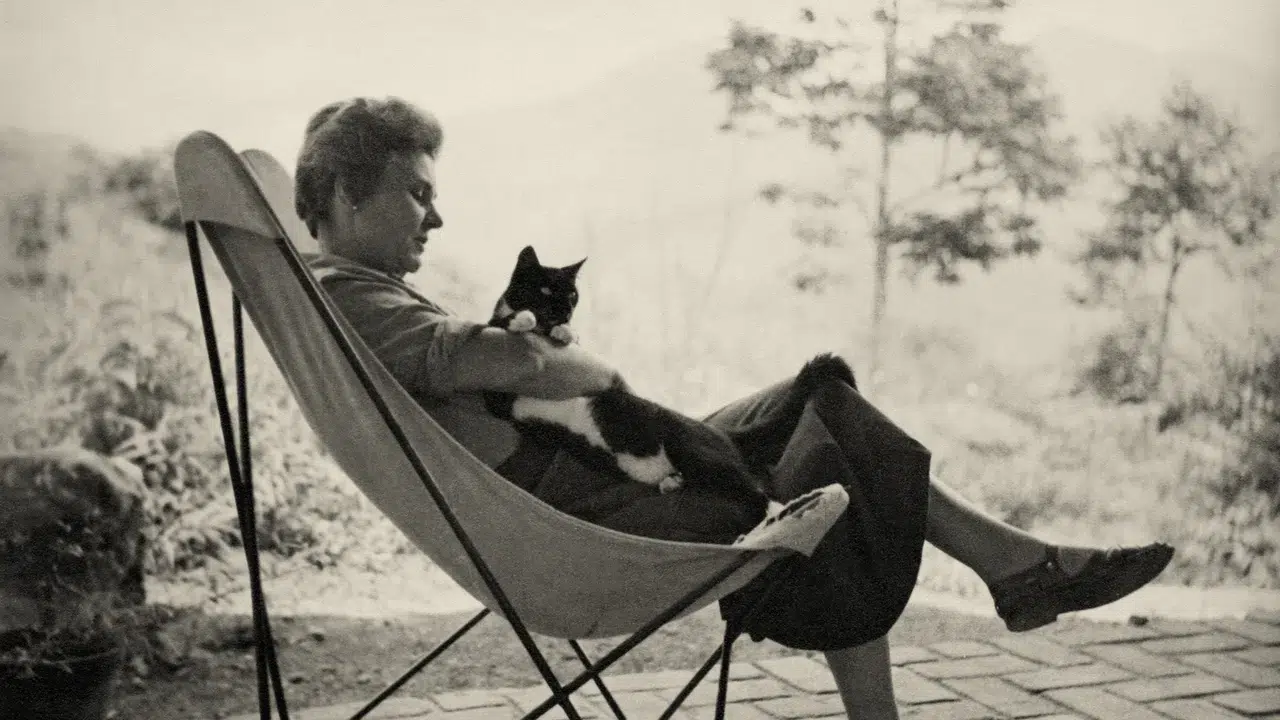

Elizabeth Bishop was a 20th-century American poet, and the name that has been turning through my mind all summer. Bishop isn’t a typical summer writer. Her landscapes are often cool and unsentimental—the silver wash of the Nova Scotian coastline, the untidy activity of a harbour in Key West. Yet here I am, sitting on a pebbly beach, a salty copy of Bishop’s Collected Works in my beach bag. Bishop’s connection to summer is not sun-drenched escape, it is a kind of drifting attention; a perfect casualness; a delight in details and fleeting moments—all qualities I associate with long summer days.

Bishop is often described as a difficult poet. When I first read her work, I struggled to make sense of it—only to realise that it doesn’t ask to be made sense of, so much as experienced. Bishop is a poet of close observation. In a review for Harper’s Magazine the poet and critic Randall Jarrell once compared her to Vermeer. Bishop was an amateur painter, and often expressed a preference for the sister art: ‘I wish I’d been a painter […] that must really be the best profession—none of this fiddling with words.’ Many of her poems frame a scene, as though looking at a painted canvas, and capture it in miniaturist detail. Her work is full of strange and beautiful observations, but her gaze shifts, thoughts trail unfinished, and meanings remain unclear. I have grown to love her precisely for these reasons—they are, to me, what make her the poet of the season.

Bishop’s poems absorb readers in a poetic moment, suspending their sense of a clear point of view. They are intentionally disorientating, and delight in their own distraction. In ‘The Map’, a poem from Bishop’s debut collection, North and South (1946), the land of the North Atlantic is presented as an imagined map:

Land lies in water; it is shadowed green.

Shadows, or are they shallows, at its edges

showing the line of long sea-weeded ledges

where weeds hang to the simple blue from green.

The poem begins with something simple, but unravels with every line. It invites us to lose ourselves in its specificity—to listen to the lovely hush of ‘shallows’ and ‘shadows’; to imagine the vibrant green of weeds dangling in water.

This kind of meandering thought reminds me of the way my own mind travels in summer. It feels indulgent to look closely at what is in front of you—to let your mind wander across, below, and beneath a scene. In Bishop’s poems, her gaze becomes hard to follow. What begins as grounded observation usually dissolves into something more slippery—but the overall impression is mesmerising. In ‘At the Fishhouses’, first published in The New Yorker in 1947, the image of an old man netting in the twilight gives way to an atmosphere of silver:

All is silver: the heavy surface of the sea,

swelling slowly as if considering spilling over

The poem becomes a shimmering surface: ‘beautiful herring scales’, ‘creamy iridescent coats of mail’, ‘sequins on his vest and on his thumb’. Its final image is the water:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn

The scene is dazzling, but it resists clarity. It remains a reflective surface we cannot see through, but the experience of looking is the point. Bishop doesn’t ask us to understand her poems. They drift—and invite a kind of reading which does the same. They do not offer clear meaning, but something more pleasurable: an unexpected image, a beautiful fragment, a mood.

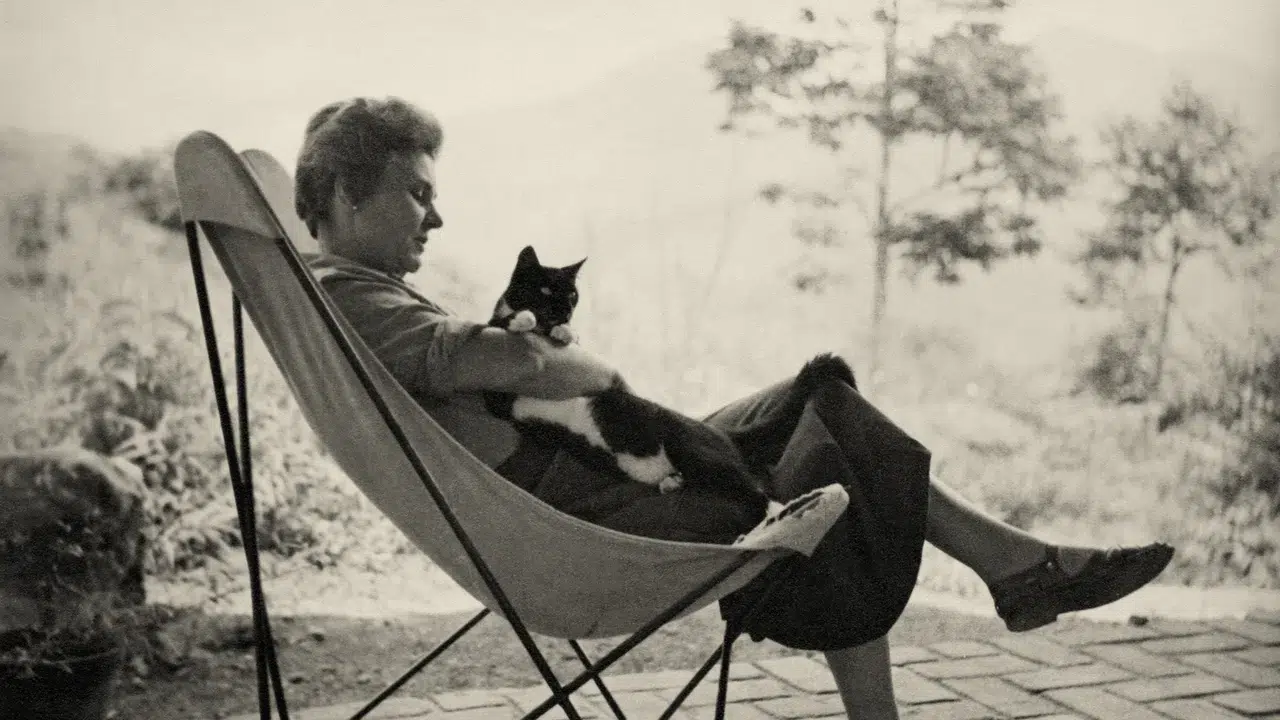

A book of Elizabeth Bishop’s works. Photo by Carolina Julius

Bishop is not a sentimental poet, but what she touches becomes luminous. Her voice has a cool reserve, which makes it feel fitting for summer, but her attentiveness to the world gives her poems warmth.

In 1976, Bishop won the Neustadt Prize for Literature—often referred to as the ‘American Nobel’. In her acceptance speech she remarked, ‘What one seems to want in art, in experiencing it, is […] a self-forgetful, perfectly useless concentration.’ This is what we look for in summer—to be absorbed, distracted by beautiful things. Bishop’s poems lend themselves to this kind of useless concentration—the kind which asks nothing of us except that we allow ourselves to be immersed, taken somewhere else.

Bishop’s life was full of displacements. She was born in Worcester, Massachusetts and grew up in Nova Scotia; at various points she lived in New York and Key West. In 1951, she travelled to Brazil on a fellowship from Bryn Mawr College, intending to stay for two weeks; she would remain for fifteen years, sharing a home with her lover, the architect Lota de Macedo Soares. In ‘Brazil, January 1, 1502’ she describes her arrival:

Every square inch filling in with foliage—

big leaves, little leaves, and giant leaves

blue, blue-green, and olive

Bishop’s poems carry the freshness of first encounters, perhaps born of a life spent moving between cities and continents—a sensibility that summer seems to echo, when even the familiar takes on unexpected beauty. In ‘Seascape’, a single sentence unfolds a world of detail: ‘herons got up as angels’, leaves ‘edged neatly with bird-droppings like illumination in silver’, a fish jumping ‘like a wildflower in an ornamental spray of spray’. Bishop’s eye moves between scales both miniature and vast, paying equal attention to beauty—from the entire celestial seascape to the mangrove leaves, gilded with silver bird-droppings, until the whole scene looks ‘like heaven’.

Bishop is not a sentimental poet, but what she touches becomes luminous. Her voice has a cool reserve, which makes it feel fitting for summer, but her attentiveness to the world gives her poems warmth. In ‘Apartment in Leme’, written from Bishop’s flat in Rio, her speaker chides the sea: ‘you tarnish our knives and forks’; ‘you frizz / her straightened, stiffened hair’; ‘You smell of codfish and old rain’. But these domestic complaints take on a strange beauty: the silver coffee pot, oxidised from salty air, ‘goes into / dark, rainbow-edged eclipse’. Beneath the speaker’s emotional reserve is a palpable sense of the sea’s quiet pull, as it breathes heavily in the background: ‘We live at your open mouth, oh Sea, / with your cold breath blowing warm, your warm breath cold’.

Every season has a feeling. If summer has its own mood, perhaps we look for it in the things we read—this year, I have found it with Bishop. Her poetry finds beauty in unusual places, but it does not linger—letting fleeting moments of observation pass. The result is a kind of effortless perfection—the kind of thing we all hope for in summer. On a June afternoon in 1978, a few days before leaving for North Haven—the small Maine island where she summered each year—Bishop reflected on her own seasonal mood:

This summer I want to do a lot of work because I really haven’t done anything for ages and there are a couple of things I’d like to finish before I die. Two or three poems and two long stories. Maybe three.

Whatever I find myself doing this summer, Bishop will remain in my beach bag.

Foot Note

5 summery poems by Elizabeth Bishop

North haven

The Bight

Questions of Travel

A Miracle for Breakfast

At the Fishhouses