In one of three essays exploring the allure of islands on screen, we consider how Antonioni used the surreal notes of Sicily as a backdrop for his silent, strange love story.

Sicily. What really happened that day on the island? When a group of friends sail around the coast of Sicily, one of their party—a moody, disappointed young lady named Anna (Lea Massari)—suddenly disappears. In any other film, this is a great set-up for a thrilling finale. Perhaps she was murdered, committed suicide, kidnapped, or simply fled. But in Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura, the viewer must be content without ever knowing.

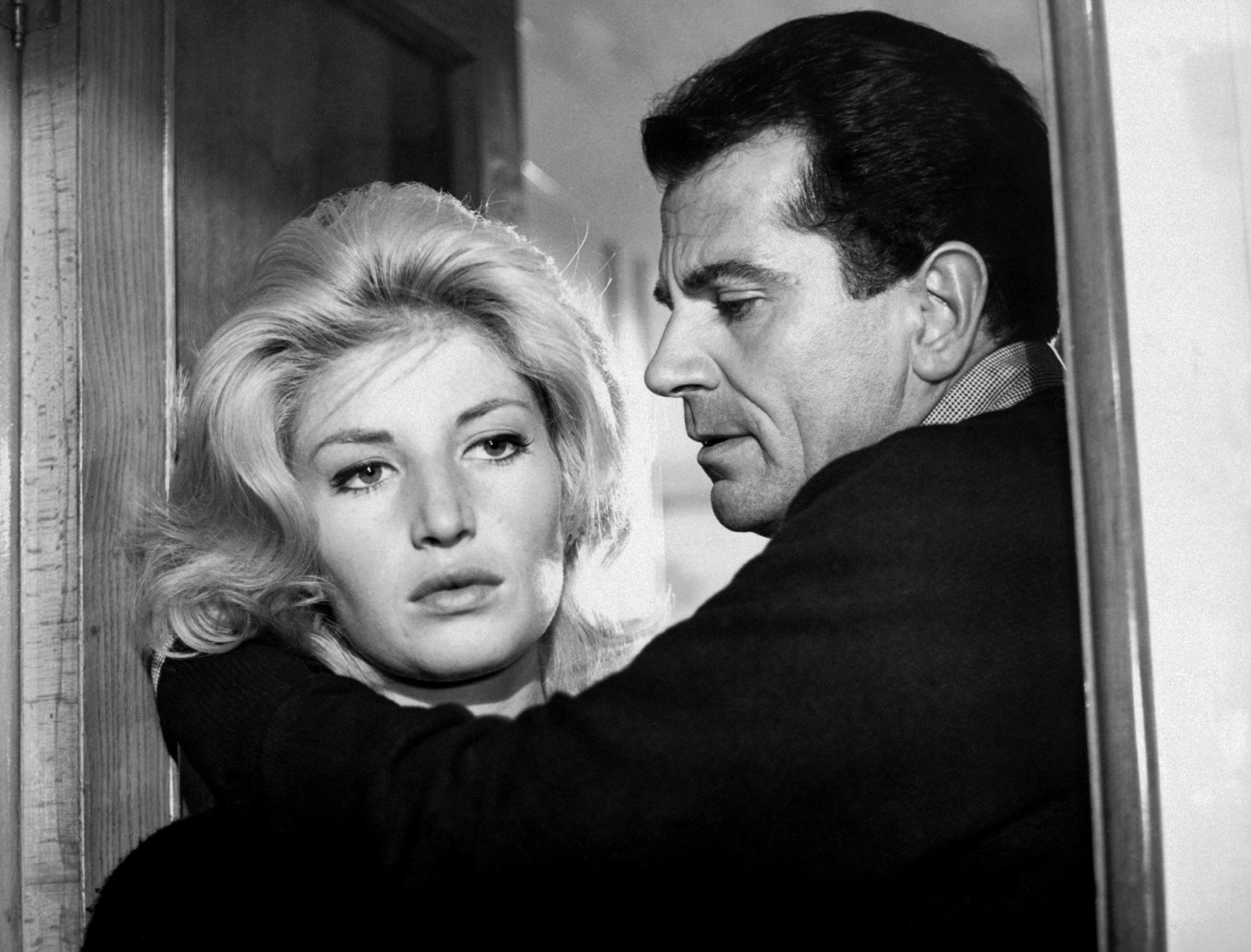

Instead, the plot turns into a love story between the woman’s partner Sandro (Gabriele Ferzetti) and her best friend Claudia (a quietly alluring early Monica Vitti performance), who are drawn together either through their sense of loss, or because of something much more sinister in Sandro’s intentions. The result is that our impressions are challenged on what a movie’s narrative could, and sometimes should, be—particularly when it comes to the traditional love story. When it was first screened at Cannes, L’Avventura earned a mixed response from the crowd—with catcalls overheard in the auditorium. But for critics, it spelled a new cinematic language, heralding Antonioni as the star of European cinema. Today, it remains a classic, and its freshness is not lost on contemporary audiences.

This is a strange film; not in the way that convoluted or desperately-experimental works are—but because there are moments when we are awed by our own confusion: in the hands of a master orchestrating the tensions and questions that erupt in our heads. In the early scenes, L’Avventura promises a little of La Dolce Vita’s glamour, or the drama from Antonioni’s previous movies. But it betrays us with the surreal, the isolated, the alien; almost like an eerie ghost story, silence permeates the coastline or the Southern Italian ruins that Sandro and Claudia wander through. There is also romance—but to what extent we believe in it just encourages more questions, drawing us back to that day on the island. The boat. The young woman. And that question returns: what is truthfully happening? As Claudia and Sandro fall in love, Anna—absent since the start of the film—haunts each scene like a wronged phantom. Without being on-screen, she feels ever-present; right up to the end.

Monica Vitti and Gabriele Ferzetti in L’Avventura (1960). By Michelangelo Antonioni.

It is a film that presents us a series of journeys, or adventures, into the mind, through the Southern Italian landscape, and into a romance that itself appears to be an open question.

We might not get the answers, but L’Avventura isn’t concerned with them. It is a film that presents us a series of journeys, or adventures, into the mind, through the Southern Italian landscape, and into a romance that itself appears to be an open question. L’Avventura would prove to be a creative success for Michaelangelo Antonioni’s career as an artist. It defined the films he made going forward, forming the first part of his ‘trilogy on modernity and its discontents’ with La Notte (a work that observed alienation in an urban setting, and starring Jeanne Moreau and Marcello Mastroianni) and L’eclisse, with Alain Delon. In all three films, he reunited with Monica Vitti—the antithesis of Sophia Loren’s extroverted, busty Italian woman, and somebody whose glazed stare, quiet beauty, and waif-like figure gave the audience a more intellectual Italian leading woman; a mysterious actress, who also had the air of a lost and complex person seeking answers.

While Sandro’s bullish nature has moments of violent expression; particularly when he confronts a group of youths, Vitti’s Claudia is quiet, clearly innocent, and pensive. By the film’s ending, we still want to know what happened that day on the island. But our deepest questions are about both Sandro and Claudia— and whether the love that begins to spark from the turmoil of Anna’s loss has any truth in it.

Read next: Islands on screen: Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli (1950)

Read next: Islands on screen: Capri in Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris (1963)