Blue Road, a new documentary about Edna O’Brien captures the life of the writer, not as tidy literary retrospective, but as something poetic, chaotic, funny and bruised. Like the woman herself.

Before Sally Rooney, there was Edna O’Brien. Before the situationship of Connor and Marianne in Normal People, before the millennial malaise of Conversations with Friends, there was O’Brien, writing about how “sometimes, one word can recall a whole span of a life” and being “restless for crowds and lights and noise” in a Dublin that wore its fairy string lights like a “necklace”. Before Connor and Marianne in Normal People were having steamy sex, O’Brien’s heroine Kate was desperately trying to rid herself of her virginity: “all the perfumes, and the sighs, and purple brassieres, and curling pins in bed, and gin-and-it, and necklaces had all been for this. I saw it as something comic and beautiful…[T]rying to undress under a dressing gown is a talent you must develop,” she writes.

O’Brien wrote the young, Irish, female experience, and she made being a young girl sublime and sordid and silly and sardonic, sometimes all at once, back when writing about such things—in 1960s repressive Ireland—got your books banned. She was a cause célèbre. A girl from rural Ireland who dared to write about what women felt, wanted, feared, a woman who, as the Anaïs Nin line goes, was determined to have an experience when it came her way.

Sinead O’Shea’s new documentary Blue Road takes us through Edna’s life—not as a tidy literary retrospective, but as something far more human, poetic, chaotic, funny and bruised. Just like Edna herself. “Will people be running to the cinema to see a film about a 93 year old woman?” director Sinead O’Shea laughs, her blue eyes sparkling over our Zoom call.

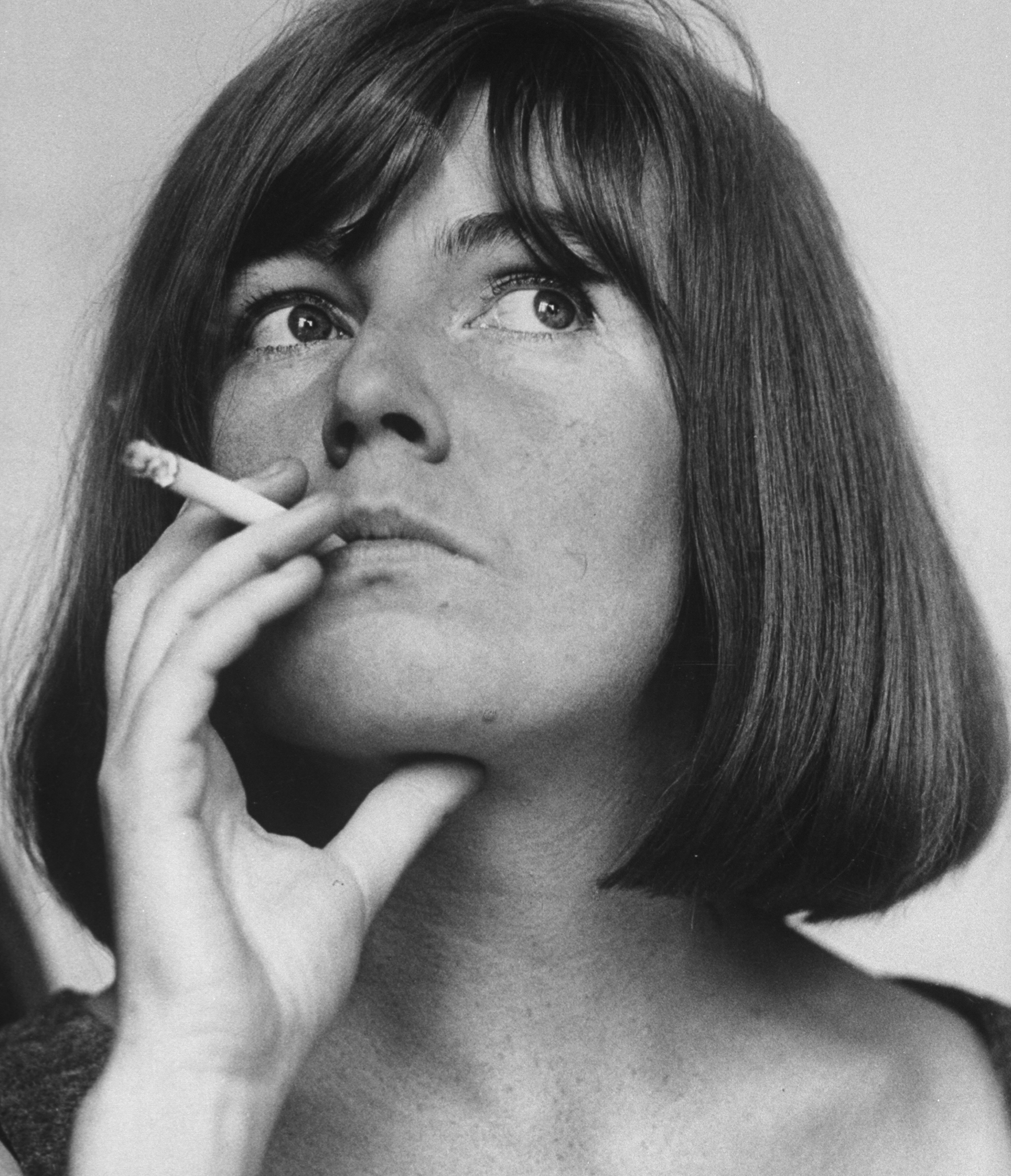

Edna O’Brien

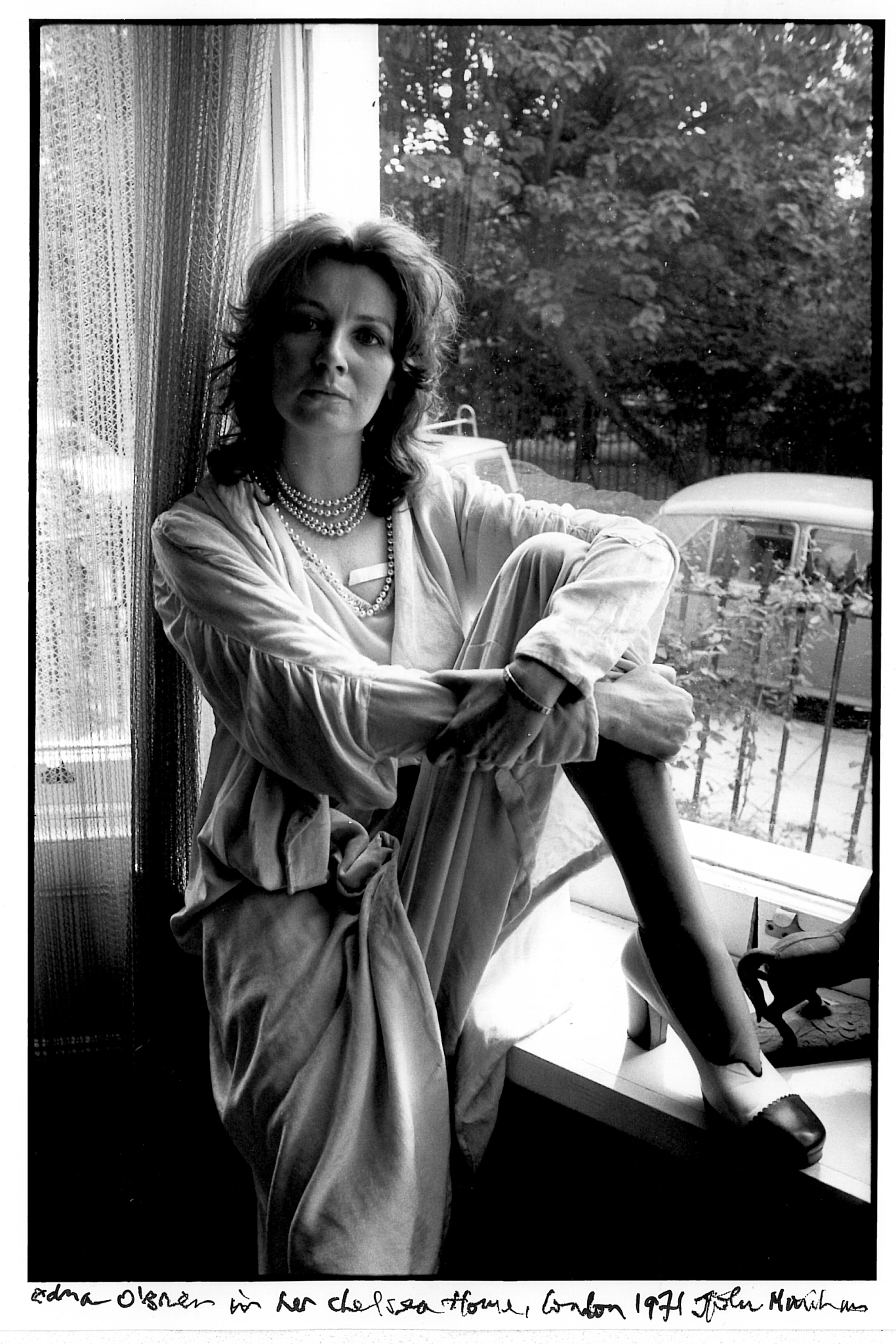

Edna O’Brien was born in 1930 in County Clare, into a country ruled by the twin forces of the Catholic Church and the patriarchal Irish State. By 19, she was married and living in Dublin. By her late twenties, she was divorced, alone, with two kids, living in London. By 30 she had written her first book The Country Girls (within 3 weeks, natch), a work of autofiction that tells the story of Kate and Baba, rebellious and mischievous Irish convent girls always looking for trouble, and like Edna herself, hungry for adventure. “I was ravenous, for food, for life, for the stories I would write. Except everything was effervescent and inchoate in my excitable brain.”

She was a convent girl turned overnight literary sensation; a bon vivant of the Chelsea and Mayfair Swinging Sixties, seduced by Robert Mitchum (“his honey coloured body”, which sounds like an Eve Babitz line, is how she fondly remembers their night together in her memoir Country Girl) and booty-called by Richard Burton (“he thought I was more libertine than I was.”) Paul McCartney sang her sons to sleep and Marianne Faithful sang Yeats poems to made up music while stoned in her living room. She took acid with R.D Laing and holidayed with Gore Vidal. “I know lots of people who were more cautious,” she says in the documentary, looking back, almost with a sly smile.

She wrote more than two dozen works of fiction, short stories, non-fiction (Country Girl: A Memoir, as well as a biography of Joyce), plays, poetry, screenplays (Zee & Co, starring Elizabeth Taylor), underwent a bitter and acrimonious divorce and custody battle, lived large, lost everything, but most importantly, never stopped writing. It’s this resilience and tenacity which transcends time, something people relate to now. “Actually, one of my favourite pieces in the film is where she’s teaching herself new vocabulary like ingenuousness and winnowing and she hasn’t been to university, she hasn’t done quite a lot of things, but she really wants to educate herself. She’s really excited, she’s got a huge IQ and she really wants to be stimulated, and she’s not unaware of how mean men [in her circle] were, but she keeps going”, O’Shea says.

There is the queasy feeling watching the doc that men dominated Edna’s world. Indeed, men are a focal point of the documentary—as they were in Edna’s life.

In Blue Road, O’Shea captures this shapeshifting quality. It shows her TV talk show persona- the lioness ready to pounce, half Jackie Collins glam half pagan goddess- terrifying Melvyn Bragg with her tirade against men in which she brashly claims that the only nice thing about men is the “occasional sexual pleasure they give us”.

It features interviews with her friends (Gabriel Byrne) and her two sons Sasha and Carlo. There’s the rambunctious strong-willed girl of her private journals, moon eyed and showing a self possession even as a young girl, reflected in Jessie Buckley’s breathless narration. And then there’s her period in the 1980s writing about the IRA and Northern Ireland, and later, in the 1990s about the Bosnian War (The Little Red Chairs). There’s the most recent Edna, 93 years old talking about trauma. Beautifully, O’Shea managed to interview O’Brien before her death in July, 2024. She is frail, but still sporting a festive red lip.

“When you love Edna, you love her hardcore. Most people are either really obsessed or they just think this obsession is creepy. I was definitely in the obsessed camp,” O’Shea laughs, describing how she made the documentary for herself. “To get a chance to express a lot of things about me in this film.. I have felt that ravenousness, too”. Surprisingly, O’Shea is a recent devotee at the altar of Edna. She only discovered her a few years ago, when commissioned to write a profile on her for Publisher’s Weekly whilst a student in Dublin. She initially dismissed Edna’s work as froth. “It’s not an accident that I thought that. I studied English in college…it was really canonical, you know, the whole syllabus,” says O’Shea, referring to the boys club of Irish writing that includes Yeats, Joyce and Heaney. “But there was no place for her really within that.”

Edna and O’Shea are both products of the repressive social structures of Ireland—something that drew her to Edna’s writing. Her stories captured her own adolescence (O’Shea is from Navan, considered East of Ireland). O’Shea felt in Edna a kindred spirit, “in the country, having terrible friends, awful men around and everyone [in Ireland] propping up the whole awful structure of it”. By awful structure, of course she means the Catholic Church, which, led by Archbishop John McQuaid from the 1940s until the 70s, had a tight grip on Irish culture, enshrining women’s place as in the home. He staunchly opposed sex education. Blocked attempts at reform regarding contraception, maintaining their ban while the UK embraced the pill in the 1960s. He created a climate where any mention of abortion was taboo, ensuring that abortion remained criminal and unspeakable for decades, even after his death (abortion was only legalised in Ireland in 2018). And, while not responsible for the infamous Magdalene Laundries, his moral authority was so enshrined in society that any issues of women’s bodily autonomy was subsequently tied up in intense shame.

So, writing about sex, as O’Brien did, in this ultra-conservative, ultra-religious and institutionally misogynistic society was pretty punk. “It was just a very messed up country with very dysfunctional accountability. Quite a cowboy culture,” O’Shea says.

There is the queasy feeling watching the doc that men dominated Edna’s world. Indeed, men are a focal point of the documentary—as they were in Edna’s life. Her first (much older) husband Ernest Geblér was everything O’Brien was not: frugal, disciplined, elegant. And also, to his chagrin, not the successful writer in the relationship. The documentary shows how he would unleash his jealousy by defacing her private journal entries. “It’s so funny because he really felt like he was asserting his moral superiority but in fact he just undermines himself,” O’Shea laughs.

What makes O’Brien’s writing endure is her gift for humour. “She’s so, so, so funny”, O’Shea says to me. The Lonely Girl, O’Brien’s second book (1962) which was adapted into a film with Vanessa Redgrave called The Girl With the Green Eyes, is full of moments that make my cheeks hurt from smiling. When Kate finds out that her older lover Eugene has a wife, she perks up, asking “she’s not dead is she?” (a line that caused me to spit out my drink laughing). When someone asks her what the difference between red and white wine is, she earnestly replies that “one is red and one is white”. Her lack of self-awareness and outspokenness is refreshing and mischievous—things good Catholic Irish girls were not meant to be.

And then, of course, there’s the sex of it all, all of which looks pretty tame to our standards. “I tasted his tongue and we explored one another’s face like dogs do when they meet, and he said “wanton” to me, ” says Kate after messing around with Eugene in the back of a car. After trying miserably to rid herself of her virginity, our heroine “felt such a fool for crying in bed. Especially as I laughed so much in the daytime”, and she “just wanted to go to sleep and wake up, finding that it was all over, the way you wake up after an operation”. Hardly the stuff of Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

O’Shea’s film excels in revealing how, at the heart of O’Brien’s writing, is how connected she was to her roots, with Ireland. Despite never moving back to Ireland and remaining in England, it was her childhood home in County Clare that Edna dreamt of, its green fields and honeysuckle and wild cows and blue walls.

Tempestuous romances and one night stands with Hollywood stars aside, O’Brien was plagued with trouble in love, like her doomed, years-long affair with a British MP. It was something O’Shea was surprised to find out about, but explained the long gap in her writing, which lasted for almost a decade until The Little Red Chairs. She didn’t find eternal love but the writing, thankfully, did come back. “I think she’s quite singular, especially for older women, in that respect”. O’Brien’s hunger for life never did wane, even after money troubles forced her to downsize and bid adieu to her Chelsea mansion, to a smaller London abode. She had a period in the US teaching writing at City College, New York. One of the students she took under her wing was Walter Mosely—now an acclaimed crime novelist—who says that one day, she told him “Walter, write a novel”, and so he did, gifting him the self belief that he hadn’t had from anyone else.

In showing us the strong woman beneath the glitz, the serious writer beneath the perceived froth, O’Shea has crafted a documentary that feels as varied and effervescent as the woman herself. “She was so committed to her writing and really… she died when she couldn’t write anymore,” O’Shea tells me. “ I think she was a wonderful role model actually, for living a life that was committed to one’s art.”

O’Shea’s film excels in revealing how, at the heart of O’Brien’s writing, is how connected she was to her roots, with Ireland. Despite never moving back to Ireland and remaining in England, it was her childhood home in County Clare that Edna dreamt of, its green fields and honeysuckle and wild cows and blue walls. Her childhood of “eating bread and sugar on the stone step of the back kitchen, drinking hot jelly” with “the fields, green and peaceful, rolling out from the solid-cut stone house, and in the summertime, meadowsweet, creamy white, all along the headlands” are the first things Kate thinks of after (finally) losing her virginity in The Lonely Girl. In Blue Road, Edna says that at the end of her life, it’s not the glitz that she’ll remember the most. But “cows in the field” and her “mother’s cough” and the trees that she spent hours telling stories to.

It’s a fitting and beautiful elegy, to a home that both created her, giving her creative fuel, and later tried to destroy her. She had to pull from the “fund of history, geography and stories” and “make my own song”, she says in the documentary, and Ireland was this song.

Blue Road: The Edna O’Brien Story is in cinemas now.