As a new season starts at the BFI in London, columnist Haaniyah Angus explores her own viewing blindspots and asks why Black women filmmakers continue to be overlooked by the industry.

Like many of my ideas, this essay began with an Instagram DM to pick the brains of brilliant people I follow online. In particular, it was film programmer Rógan Graham who had caught my eye as someone I had followed for some time, someone who, like me, loved film and wanted to critically examine the work of Black filmmakers and film practices with more care. We got on the phone talking about my project on the state of the film industry and our experiences as two Black women who love film but are more than aware of the industry’s disinterest in us.

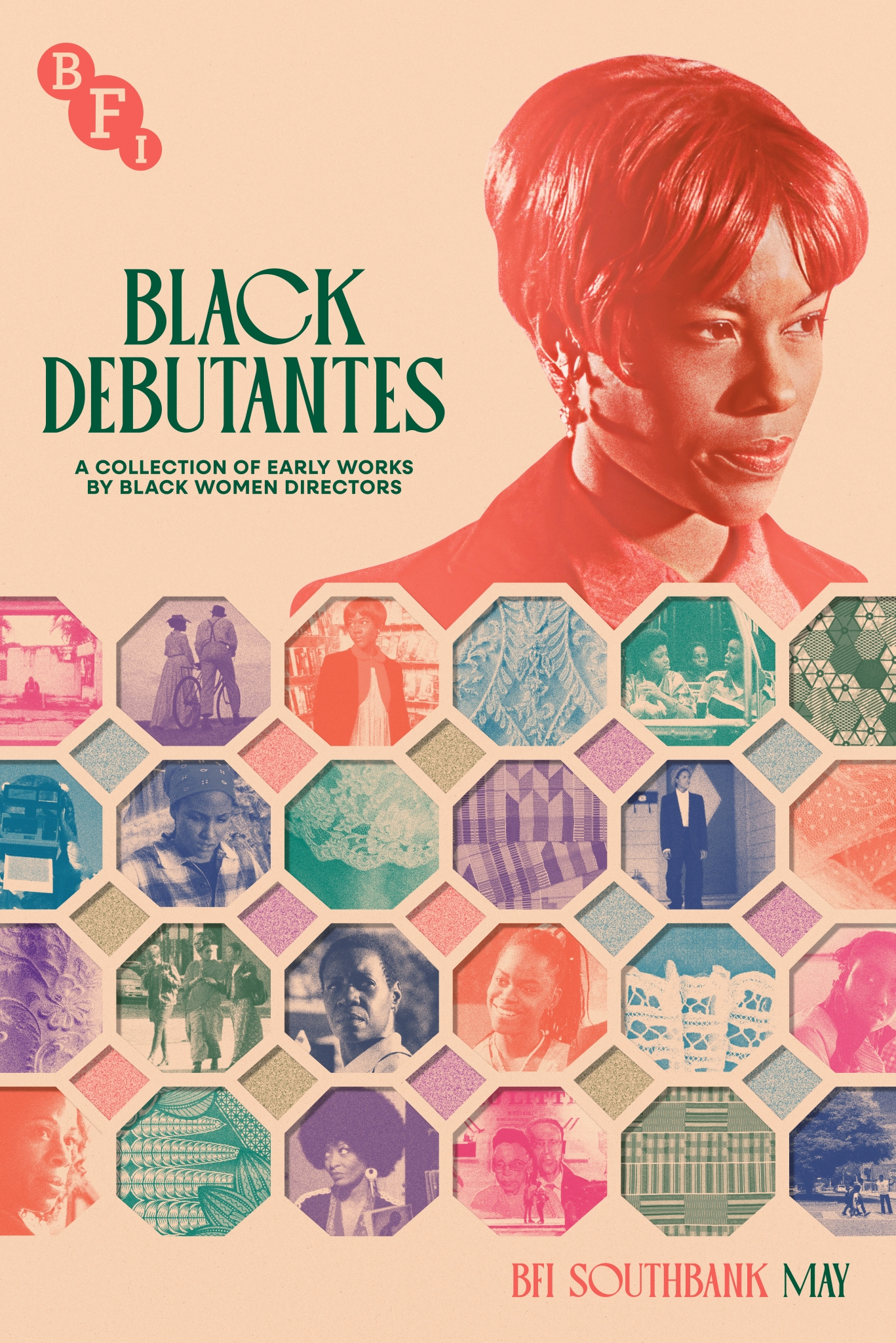

This project I was working on was subsequently cancelled, but in a twist of fate, Rógan announced that she had been secretly developing a film program for the BFI focused on the very concerns we had discussed in our earlier conversation. Black Debutantes: A Collection of Early Works by Black Women Directors is a celebration of Black women and femme filmmakers who are both underseen and underdiscussed. I’ll be the first to admit—and perhaps this might ding my credibility a bit here—that I also have a massive blind spot for films directed by Black women, not an avoidance by any means, but due to a lack of screenings as well as online archives of their films and an almost total erasure of them in my undergrad film school. Because of this, the season piqued my interest as a film lover and film critic, with it being a rare opportunity to see all these movies in one place.

For Rógan, her reasoning behind pitching the program was simply that she realised the BFI hadn’t had a massive film season for a Black woman director yet and wondered why. “I remember thinking to myself, is there a single Black woman director who has made enough feature films to hold a season? And the answer was no. Almost all of the prolific Black women filmmakers have filmographies that aren’t robust enough, not in terms of quality but literally in number, in volume, to uphold a season of that magnitude. As I was looking around and doing this research, I noticed that so many Black women filmmakers who have directed the films I love, like Calueen Smith with Drylongso (1998), have only ever made one feature film. My pitch was to look into the Black women who had only made one feature, and dig into why that is.”

The current version of Black Debutantes has expanded beyond Rógan’s initial concept by including debut films by filmmakers who went on to make more than one film. Through this Rógan has recontextualised the relationship between those with and without follow-up films. Euzhan Palcy, in particular, had her debut film, Sugar Cane Alley (1983), which won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival, followed by A Dry White Season (1989) and the musical Siméon (1992). Meanwhile, Bridgett M. Davis who directed Naked Acts (1998) did not have such a long career. Yet Rógan tells me during our chat that the lack of follow-up is not something to pity Davis for. “The more I kind of looked into people’s careers, I realised it actually kind of dismissive to say, oh, poor them, they only made one film and I’m gonna take the industry to task, or whatever, because they’ve many of them have continued living rich lives as artists, like Bridgett M Davis, who’s a successful author. What the season means to me is an opportunity to draw connections between these films and the filmmakers who often work concurrently. Instead of having a one-off screening and saying, “Oh, look at this wonderful restoration, and by the way if you don’t make it to this one, you miss it forever”, with no further conversation about the context in which the film was made, who was coming up alongside them and what could their careers had been like under different circumstances.”

The question of what if reigns heavily in both my mind and Rógan’s when discussing the different career paths some Black female directors could have taken if they had not been so constrained by race and gender. Take, for example, Amma Asante, the British director of Belle (2013). Her debut film featured in the slate is A Way of Life (2004), which centres on a young white working-class mother in Cardiff and examines the complex relationship between poverty and racism. However, nearly every film Asante has made since then has been a period piece, often based on the experiences of her mixed-race or Black protagonists in an interracial relationship, or examining the complexity of biracial identities in eras where being mixed-race was more fraught (Where Hands Touch, 2018).

In Rógan’s opinion, Asante’s career is fascinating, as, unlike most Black female filmmakers (particularly those from Britain), she has created a sustainable career. “You know, I’d like to speak to her and talk about that journey, and if a Black woman making a film about race is more acceptable than making films about the white working-class communities, and how she was able to make more than one film. It feels to me that nobody has asked her about that, so maybe I’ll ask her one day. She’s very much alive and active and working and can speak for herself and speak for her career, unlike some of the women we’ve been talking about, so that’s where my interest lies.”

In the case of Asante, I will be the first to say that her films are not for me, perhaps coloured by an unfortunate experience with her and her producer when I was a budding film writer. However, my eye-rolling annoyance at the insistence of making interracial relationships the focal point of her filmmaking without giving Black women airtime on screen doesn’t mean that her films aren’t worth the same level of analysis and academic scrutiny that many Black male directors, such as Spike Lee, Steve McQueen, Barry Jenkins and John Singleton have been granted by both the film industry at large as well as audiences. I can already see the arguments by placing her name amongst those greats in Black cinema being “she should make better films than they have” or “those filmmakers engage with Blackness in a way she doesn’t”, and both could be true, but the point of Black Debutantes is that for many Black female filmmakers including Asante, the question of why certain choices were made or not made has not been at the forefront of our discussions.

There have only been a handful of Black British female filmmakers who have been given theatrical distribution in the UK for a feature-length film. Amongst those are Raine Allen Miller, Ngozi Onwurah, Destiny Ekaragha, Dionne Edwards, Adura Onashile, as well as Amma Asante. When asking Rógan in a follow-up conversation if I had missed out on any more, we both realised that we couldn’t think of anyone else. That in itself is a clear indicator of just how poor the support for Black British female filmmakers remains even today. I reflect on my own experience during my film degree. I recall Sofia Coppola and Andrea Arnold’s inclusion in our classes, but not any Black women, let alone Black British women, across the numerous films we watched during my three years of study.

There have only been a handful of Black British female filmmakers who have been given theatrical distribution in the UK for a feature-length film. Amongst those are Raine Allen Miller, Ngozi Onwurah, Destiny Ekaragha, Dionne Edwards, Adura Onashile, as well as Amma Asante.

Haaniyah Angus

Poster for the BFI Southbank’s ‘Black Debutantes’ season.

I wonder if it’s simply just racism or if it’s disinterest. Honestly, I can’t tell which is worse, and does one exist without the other? Are you disinterested because you’re racist, or is it because of racism that you find stories made by not just Black women but Black people in general tiring? I think back to our recent awards season and the discourses I noticed both online and within my circles where even well meaning people told me they didn’t want to watch Nickel Boys because they feared it would be another ‘trauma film’ and ‘issue film’ and I find that not only fascinating but incredibly dismissive. Why is it that a film like A Real Pain escapes the title of an ‘issue film’ when, similar to Nickel Boys, it’s about stories that are often untold and people that are overlooked? Within pain and trauma, there is joy, there is family, there is love, and there are all these things that are quintessential to the Black experience. To me, it reveals more about how someone perceives Blackness and the way they view the humanity and intellect of the characters, as well as that of the filmmaker, than anything else.

For Rógan, this boxing in of Black stories is part of why the season holds so much significance. “Drylongso is about teenagers and gang violence, but it’s also about a teenage girl trying to finish her art project, and the men in her community are so multifaceted. Our perspectives are so multifaceted. Naked Acts is an example I always use because there are indirect themes of child sexual abuse explored through a young woman taking on her first acting role in an indie film and not wanting to show her body. It’s incredibly funny, because it’s about kind of sleazy male directors trying to put actresses against each other, who are giving him a finger in the end.”

Many of the films included in Black Debutantes share the same multifacetedness Rógan describes: they are funny, complex, serious in nature, yet light in tone. The complexity of the Black experience and Black filmmaking is something that we both hold dear, but it is more than clear that there is a lack of nuance when it comes to audience and industry perception. Toward the end of our discussion, Rógan says, “Maybe they [audiences and the industry] aren’t ready to hold those two truths, or multiple truths, in their heads, realising that it doesn’t have to be an obligation to engage with this work. It’s enjoyable because you’re watching well-crafted pieces of cinema.”

Black Debutantes: A Collection of Early Works by Black Women Directors takes place at BFI Southbank from 1 – 31 May, with select titles on BFI Player from 5 May