“It is only the logic of beauty.” The Portuguese film director discusses Grand Tour, a tale of travel on the Orient told in colour and monochrome.

The COVID lockdown, as depicted by Miguel Gomes and his wife Maureen Fazendeiro in The Tsugua Diaries (2021), was a time of peace and beauty. Dancing to ‘The Night’ by Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons in a farmhouse in rural Portugal, Gomes and Fazendeiro appeared in the film as fictional versions of themselves alongside Crista Alfaiate—the Xerazade of Gomes’s epic three-part adaptation of Arabian Nights (2015). For Alfaiate’s next trip with Gomes, she breaks out of the pandemic’s restrictions and embarks on her very own Grand Tour (2024). Directed by Gomes, and penned by a team including Fazendeiro, the film is a sparkling odyssey across the Asian continent in 1918 and the present.

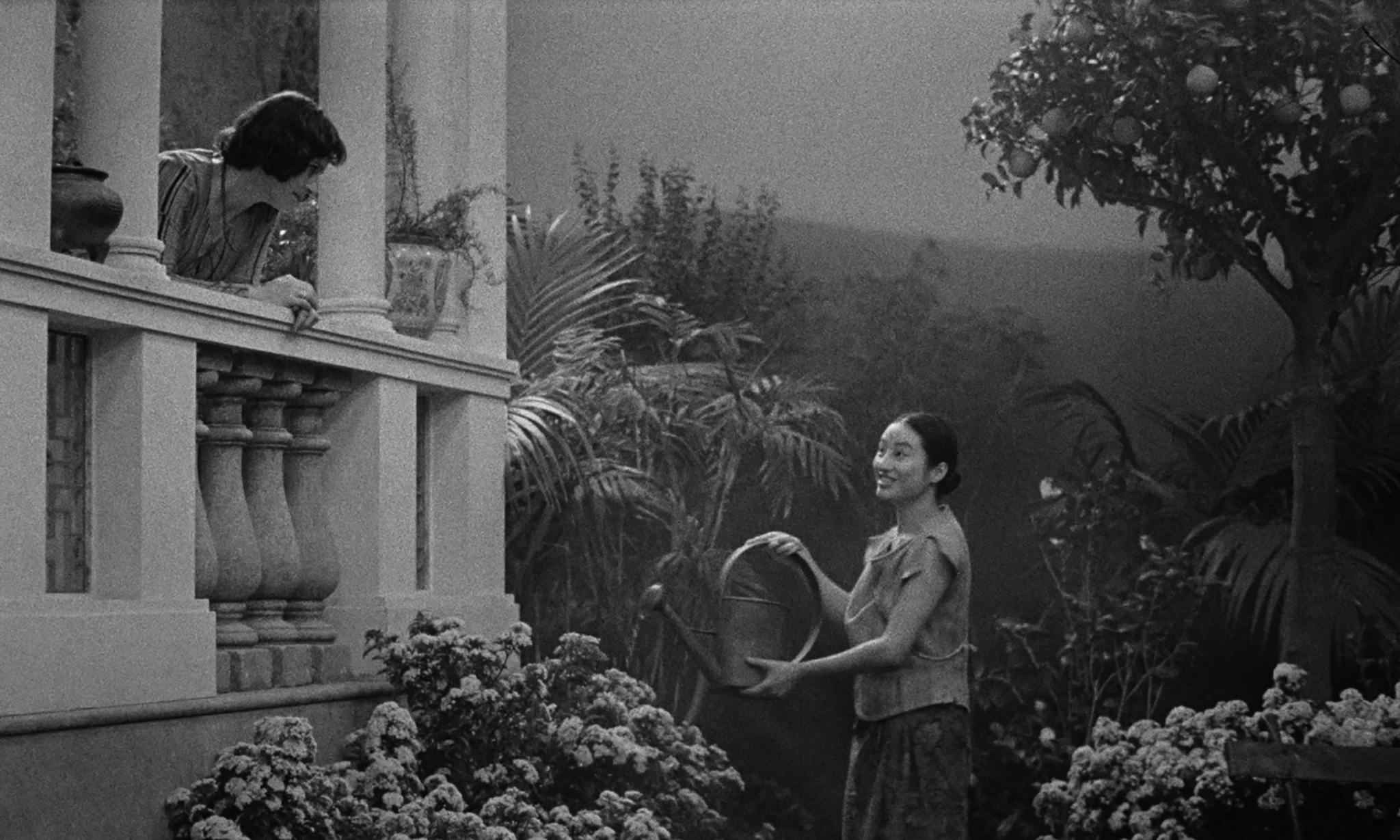

Grand Tour is a quintessential Gomes film. It looks and feels like Tabu (2012), which similarly moved between past and present to explore the height of European colonialism and its later impact, shot in dazzling black-and-white. Grand Tour features splashes of colour in its contemporary documentary scenes showing life in Asia today, acting as ellipsis to the central narrative, a tour of Asia taken by Europeans in the early 20th century. Like Tabu, the film is bisected into two acts—the first following civil servant Edward, played by Gonçalo Waddington, as he awaits his fiancée Molly, played by Alfaiate, before he flees; the second accompanying Molly as she follows Edward across Asia. The futility of her wild goose chase slowly dawns on her.

Like all of Gomes’s films, Grand Tour moves between cinematic genres, treading lightly between classic Hollywood comedy and European tragedy. Gomes orchestrates several lavish composed sequences, using Western and Eastern music to explore global cultural tensions at the close of the First World War. The Grand Tour was staged as a tourist trip, but how lightly can travellers tread when they step into other people’s land?

Lillian Crawford: What research did you do into the Asian Grand Tour prior to filming?

Miguel Gomes: The Asian Grand Tour was something that I knew just before making this film. It was an itinerary going from west to east, normally coming from a point of the British Empire to India or Burma, and finishing in China. So there were some writers like Somerset Maugham doing this itinerary and writing about them at the beginning of the 20th century.

LC: How much inspiration did you draw from W. Somerset Maugham? Was it just his travelogue writing like The Gentleman in the Parlour, or did you also refer to his novels?

MG: I don’t think he’s my favourite author. But since I was a teenager or even in childhood, I read his books and it was a big pleasure. I’ve read all of the best-known of Somerset Maugham’s books, like The Razor’s Edge. But I never thought about adapting them as a film. But it happens that I also like to read travelogues, and I’m always quite puzzled by the way a writer sees places and sees people living in these places. It interests me as almost a literary genre. So by chance I was reading The Gentleman in the Parlour, then I had this idea: “Is it possible to do a very strange adaptation of what I’ve just read?” Which is a situation in the description in three pages of this couple that would be like Molly and Edward in the film. So this couple, a bride and groom, with her chasing him across Asia. And also do the travelogue which Somerset Maugham was doing in the book. A travelogue can only be done in the present. So is it possible to do both things? In the book, there’s no point of view of the woman. There’s only the point of view of the man running away. At the same time, I wanted to cross these with the places, follow their itinerary and do the travelogue in the book.

LC: When you were filming the travelogue, documentary parts of the film, were you thinking about the narrative and how the two might be edited together?

MG: I was trying to avoid the blank page. Because it scares me. There’s no limit in the blank page, so I need something coming from the outside, and not only from my imagination. I need exterior elements to come and provide a context. Then I will react to it by creating fiction. This was the proposition I made to the producer, to do the trip before and shoot this, and then we’ll come back to Lisbon and we’ll write the story. Thinking about where the sequences would go in the narrative, creating a context for every scene of the film.

LC: This often becomes a blending of colour and black-and-white in moving between the present-day travelogue and the historical drama of the film. Where did the idea for using different textures of film stock and colour come from? I know that you describe a lot of your films as taking inspiration from The Wizard of Oz.

MG: You’re right, but I never thought about this. The Wizard of Oz uses black-and-white and colour, which is one of my obsessions; but in the film, you have black-and-white representing daily life when Dorothy is in Kansas, and then she goes to the land of cinema, a Technicolor place. But in this case when I was filming, the colour appeared by chance. I was shooting on film stock, on 16mm, which is no good at night in black-and-white. So to solve that we decided to have like 10% of the film stock in colour. And then we came to Lisbon to the editing room, and we had turned the colour into black-and-white. So the film was supposed to be all in black-and-white. But maybe one month before wrapping the editing, we were already a little bit fed up with black-and-white, me and the editor, so we turned on the colour again and we were impressed. It’s beautiful. This is what is lacking in black-and-white film. It’s colour! For the viewer, it will be puzzling, because, unlike The Wizard of Oz, there’s no rational logic with this change. It is only the logic of beauty.

Cinema starts to be a little bit old by now. And so we have memories of very different kinds of things. It’s a constellation of different things that cinema was in different moments in different places of the world by now. I think it’s no good to try to mimic, to reproduce something that is gone, but in a way we can still get back something of the feeling of cinema that disappeared.

Miguel Gomes

LC: It creates a beautiful effect as colour and black-and-white overlap through the slow dissolves. This marries well with the use of music and choreography, in particular moving seamlessly from the Eton Boating Song to Strauss’s Blue Danube waltz.

MG: That was already in the script, these two songs. We wanted to have a British song, a little bit silly. And we chose the Strauss waltz because when we were researching what kind of things happened in Bangkok in 1918, we read that someone travelled to the royal palace and described a party for diplomats. The Thai people were not colonised, and apparently they were very skilled as diplomats, and so they threw these parties with all the elements of European culture for the diplomats. I remember one of the happiest days in the editing room was when, by chance, we put the two songs together, the end of the Boating Song and the beginning of the Blue Danube was the same note. So it never stopped, the Eton Boating Song transforms into the Strauss.

LC: The film also carries a lot of cinematic influence to stage these tensions, from silent comedy to screwball comedy. What dialogue are you creating with the history of cinema?

MG: The film starts in a light way, more like a screwball comedy, sometimes an adventure film. There’s this relationship with classical cinema. Then there is this moment with the opera, Il Trovatore, which is a tragedy, and this moment shows that the film is about to go to another place, to tragedy, to start to be operatic. Transforming—this is very important, this idea that the movement of the film should be changing, of how you change. Cinema starts to be a little bit old by now. And so we have memories of very different kinds of things. It’s a constellation of different things that cinema was in different moments in different places of the world by now. I think it’s no good to try to mimic, to reproduce something that is gone, but in a way we can still get back something of the feeling of cinema that disappeared. I brought the idea of screwball comedies to the actress [Crista Alfaiate] when we were discussing how to act in this film. I said you can watch Bringing Up Baby, and see Katherine Hepburn and Cary Grant in this film, playing in a completely non-naturalistic way and having fun. That’s contagious. But of course then the film changes, and so there are maybe other memories of films that can appear in the background or in the mind of the viewer that is watching the film. But I never thought about it with this one. I was doing the film, but somehow it’s already inside me. The memory of it is inside me.

Grand Tour is in UK cinemas from 18th April.