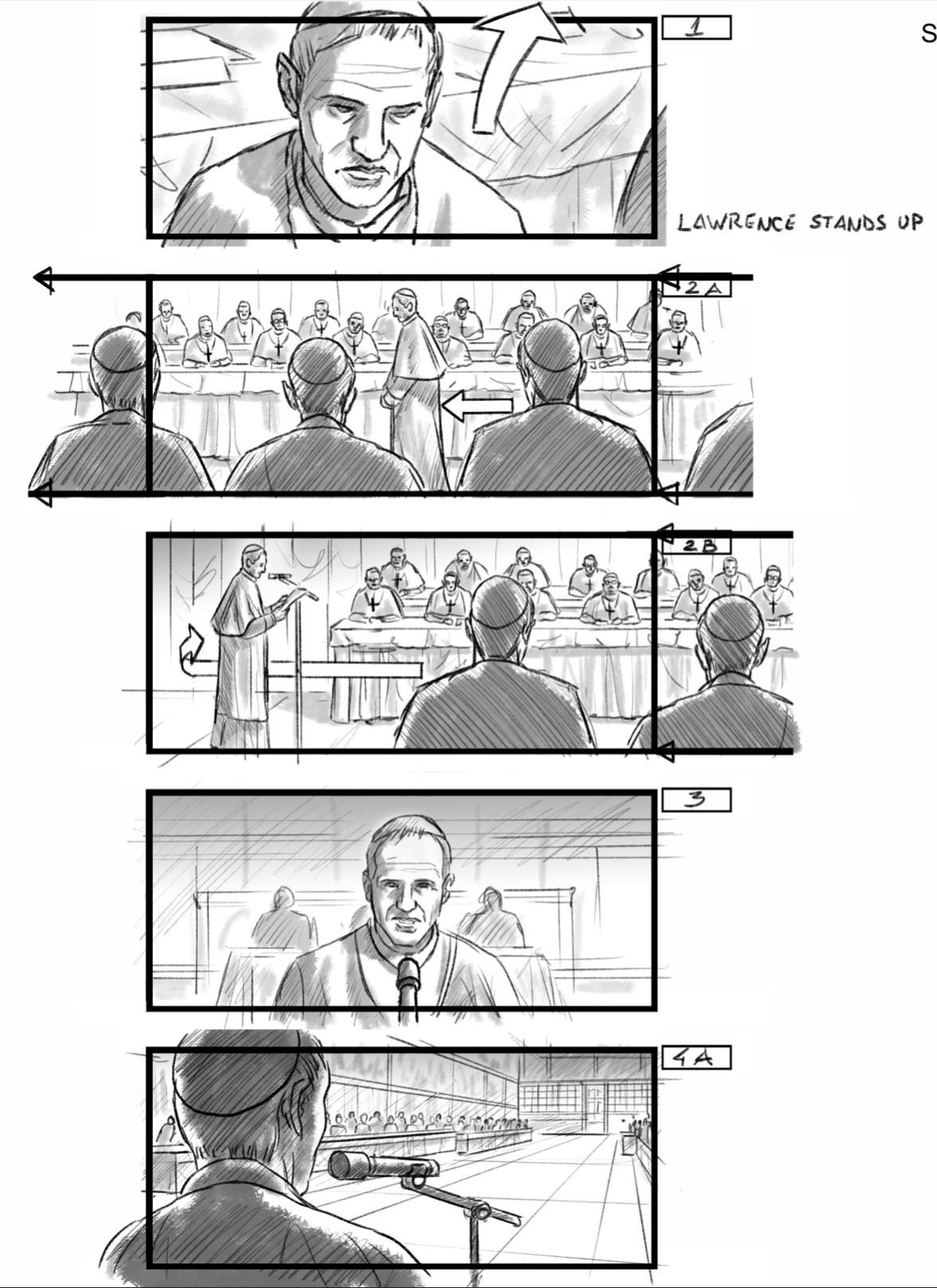

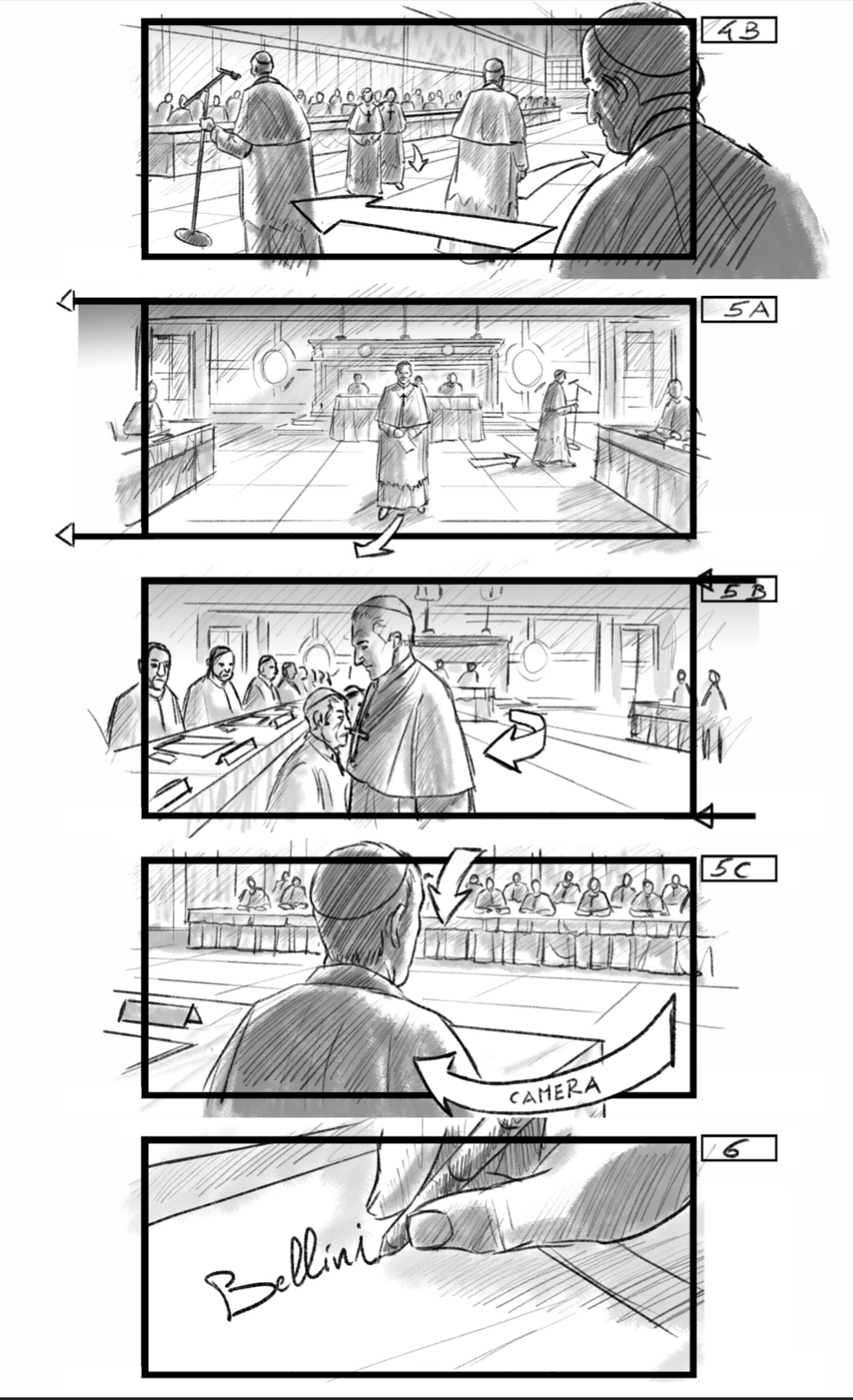

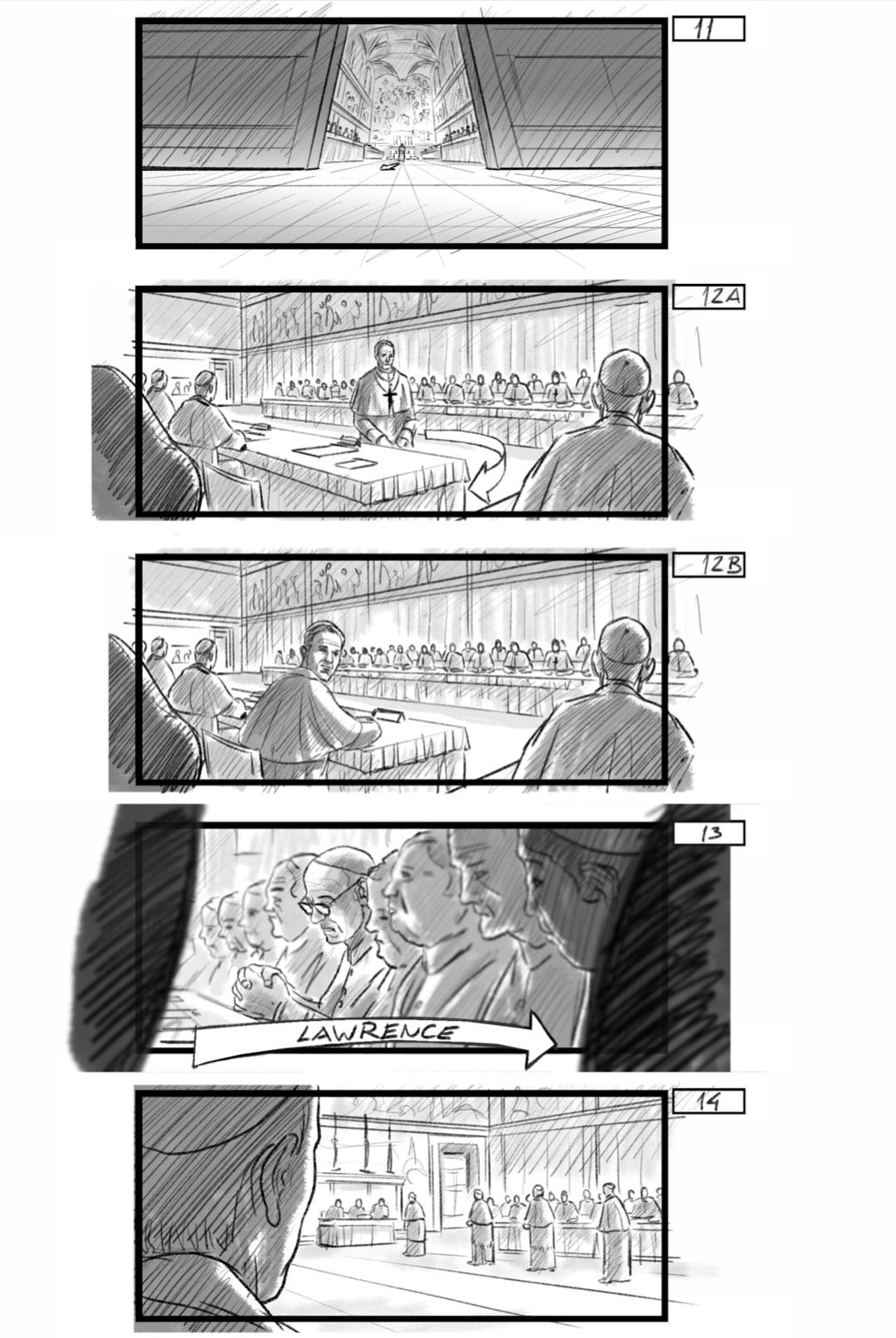

In his own words, the acclaimed director describes the inspirations and stylistic decisions for his papal thriller Conclave, and shares some exclusive storyboards from the film.

I was afraid of this film. Afraid because there was so much dialogue in it. Because dialogue is hard. And I usually don’t have much of it. Whenever I write the script myself, there is hardly any dialogue in the movie. Just go look at All Quiet on the Western Front (2022) and count the words. There are maybe a few hundred in it.

Maybe it is because I often don’t know what to say when I am with others. Perhaps I don’t have enough to draw on when I sit in front of the blank page. Or maybe it is because I was taught that every movie has to work even when you turn off the sound. That you have to be able to tell the story with images itself. It’s probably some old-school cinematic philosophy disseminated by my Russian emigré professors at my school, but somewhere deep inside me it stuck.

Dialogue is hard because you have to keep your innocence when you hear it over and over again—the innocent thrill that you felt when first reading the pages of your story. The thrill of working with a master of dialogue like the screenwriter Peter Straughan, who puts lines like “Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made” into the stage directions of your script. There is not a more soulful person in the world.

You have to remember the way you kept turning the page because you were eager to find out what the characters would say next. Trust that the audience may feel the same thrill if you don’t muck it up. If you resist succumbing to pretentious camera moves because you lose confidence in the power of the words as you hear them for the 50th time while you shoot them. So nail the camera to the ground and make each shot a statement. Cut away the fat and edit only where it counts.

And then there is silence. Time and images to rest your oral senses and a sea of red to stimulate your eyes. And I realise how obsessed I am with sound that orchestrates the looks exchanged by the contestants of my film. The placement of each foley, the accuracy of each sound effect. This has to be precise. No words—just breathing, shuffling feet, and scratching pencils. The swishing robes or humming fluorescents. Perhaps I pepper the silence with stabs of jagged music to shoot a jolt into the screen. To let me know what my cardinals hide behind their staring eyes, what they may feel inside their stomachs. But nothing has more power, nothing fills the air more, than the tension of silence.

Go and watch Downhill Racer (1969) by Michael Ritchie. Robert Redford is in it so you’ll enjoy it. The first time I watched that movie I learned about the accuracy of sound. It’s so spare that every sound effect is placed like a dagger. And I realise that maybe my Russian professors didn’t know everything. Maybe it’s time to move on and shed what I’ve learned. Maybe it’s time to make another movie to feel like a student again. To be afraid of the next challenge and to try to learn to overcome it.