Finding parallels with contemporary writers such as Clairo, Sheila Heti and Charli XCX, Madeleine Wulfahrt argues that Godard’s Anna Karina-led tale of fertility and female objectification resonates now more than ever.

A Woman is A Woman (1961) is directed by Jean-Luc Godard. Its heroine, Angela, is played by his newlywed wife, Anna Karina. Lights shine through blue, red, and purple gels onto Angela. She’s in lingerie, in a strip club, in Paris. It’s the start of the sixties, and the besotted Alfred, (a young Jean-Paul Belmondo) is waiting for her outside. The club is almost empty—it’s the middle of the day, and most people have places to be. For Angela, that place is the Zodiac Club. She twirls her long brown hair around her finger, not caring if stray pieces get stuck to her eyeshadow. She sings, I’m no angel… I’m very cruel… But men don’t seem to mind, because I’m very… very… beautiful…

Once her act is over, she puts her red cardigan, wool skirt and trench back on, adjusting her New-Wave bangs in the mirror. She lingers to collect something from a friend backstage. Since it’s a Godard movie, we expect it might be a letter from a scorned ex, an envelope full of money, perhaps even a gun from a lover who also happens to be a terrorist. In fact, a friend of said friend has procured an ovulation tester from a nearby hospital, and Angela can’t wait to get home and see if she’s fertile. Her boyfriend Émile, played by Jean-Claude Brialy, doesn’t know it yet, but she’s decided she wants to try for a baby. When she discovers that day is the most fertile day of her cycle, she decides she has to try right away.

I first saw A Woman is A Woman in a poor-quality transfer on my laptop as a teenager. I was charmed by Karina, Belmondo, Brialy and their feats of physical comedy—by their love triangle and fraught conversations about relationships over burnt roast beef, by Angela’s boyfriend cycling around their apartment on a vintage bicycle. When I sat down to rewatch the film a few weeks ago, I hadn’t anticipated just how prescient it would feel in 2025.

Its premise is unusual for a film made in the sixties, even at the height of France’s sexual revolution. Unmarried women in their twenties preoccupied by the decision to have children feels like a decidedly twenty-first-century subject, as motherhood ceases to be an expectation. Indeed, it has rarely felt more ubiquitous than over the last five years or so, as a flurry of albums and books have appeared which grapple with the question of whether or not to have children. There was Sheila Heti’s Motherhood, a 2018 work of autofiction centring around the narrator’s decision whether or not to have children before time runs out. Then there was Clairo’s 2021 album, Sling, a wafting exploration of motherhood inspired by the adoption of her dog, Joanie. Most recently, and perhaps most influentially, there was the 2024 song, ‘I think about it all the time’ by Charli XCX on her viral album Brat: “Should I stop my birth control? / Because my career feels so small / in the existential scheme of it all.”

In A Woman is A Woman, Angela is objectified and pursued by two of Godard’s most handsome leading men, all while offscreen, Karina was being pursued by Godard himself. And yet, as soon as Angela voices that she wants to have a baby, that she wants—nay deserves—the commitment necessary to sustain such a choice, her boyfriend turns against her. She becomes the butt of his jokes, subject to insults and infidelity. She bears all these with the detached playfulness characteristic of New-Wave heroines, threatening, half-jokingly, that if he refuses to father her child, she’ll sleep with Belmondo. Even her boyfriend seems unsure how serious she is in this, unaware until it’s almost too late just how much this betrayal would hurt him.

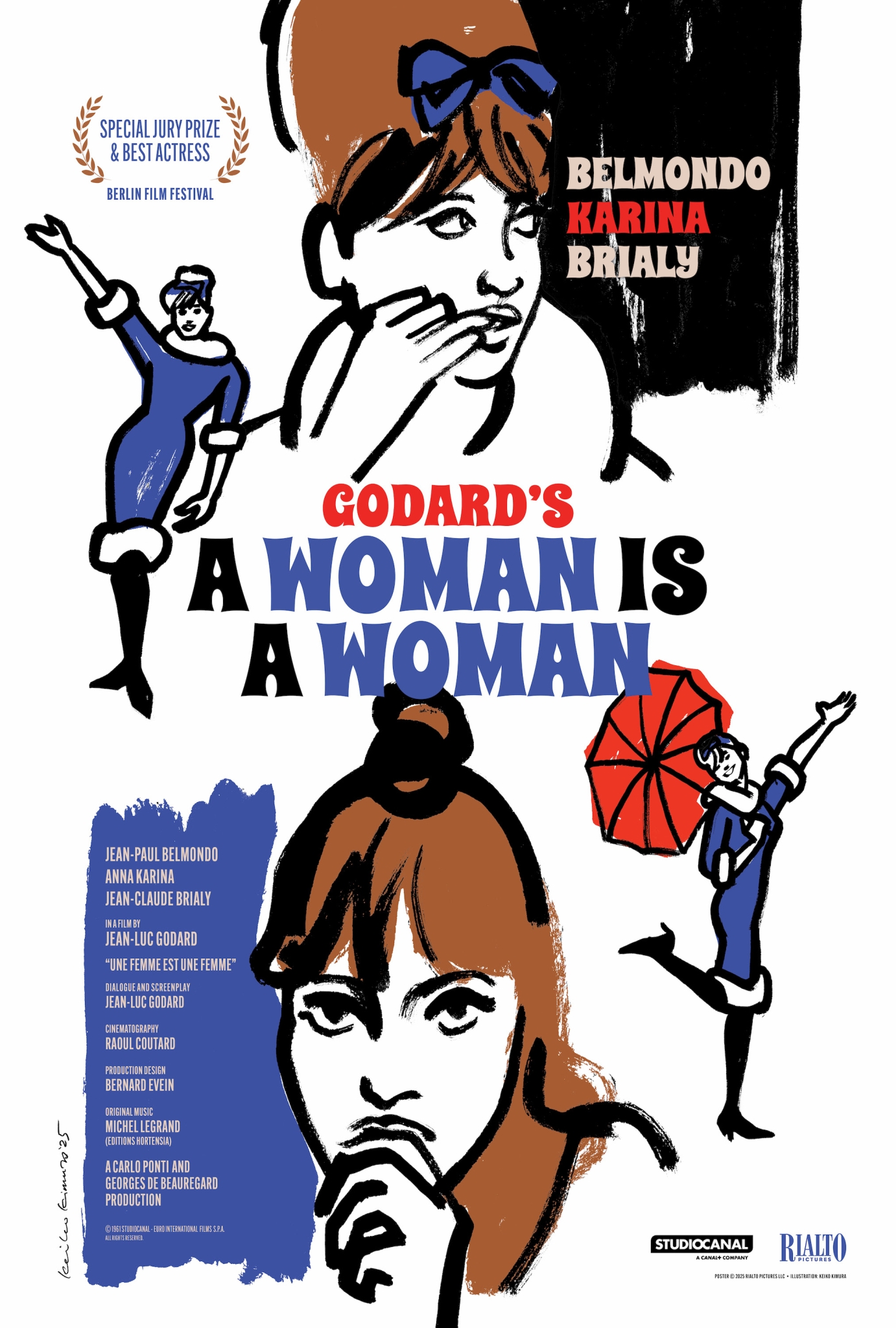

Poster courtesy Rialto Pictures.

All too often, male directors of the French New Wave liberated their female protagonists just enough to make them detached and easy-going about the way men treat them, but not enough to give them true agency. There are exceptions to this, of course, notably in the work of Jacques Demy, husband to Agnès Varda, who devoted his undivided attention to the interiority of his heroines—in his musicals The Umbrellas of Cherbourg and The Young Girls of Rochefort, Demy prizes the young girls’ perspective, rather that of those who would objectify them. Angela is a rare example of a Godard heroine whose own desires propel the action of the film. Even if her needs are often thwarted or belittled, it is her who gets the last laugh.

Rewatching the A Woman is A Woman, I thought of Charli XCX, of her empowered, sensual performances, and of how surprised I had been by her vulnerable lyrics on ‘I think about it all the time.’ I was struck by how little has changed—how, even as childlessness becomes less and less stigmatised, women continue to be made vulnerable by the realities of their fertility. Over dinner this summer, a friend and I, both in our mid-twenties, were shocked to discover that we had been receiving the same targeted ads on Instagram, promoting a medical program which would allow us to pay to freeze our eggs by selling half the eggs harvested from our ovaries. We laughed about it at the time, yet I could tell we both felt cornered: freezing eggs was something many of my friends had discussed with me, but none of them could afford to do. The advertisement provided a strange solution which felt intensely unsatisifying: put off worries about fertility at the price of sustaining the absurd healthcare industry of late-stage capitalism.

All too often, male directors of the French New Wave liberated their female protagonists just enough to make them detached and easy-going about the way men treat them, but not enough to give them true agency.

Madeleine Wulfahrt

A Woman is A Woman has lingered in cultural memory for its sexy set pieces: Angela’s striptease, her flirtatious domestic rituals. And rightly so—they’re expertly done and utterly beguiling. I think of Angela every time I fry an egg, how she flips hers into the air, goes to answer the phone, then comes back to catch it in the pan. It’s easy to dismiss A Woman is A Woman as one of Godard’s fluffier efforts, but to do so would be to miss the point. Whether it was his intention or not, Karina’s Angela emerges as one of the New Wave’s more fascinating female leads, catalysing emotional complexity as seamlessly as she fries that egg. For all her proto-Manic-Pixie-Dream-Girl posturing, Angela’s is more fully-fleshed than she might seem.

Though Godard frames Angela’s repeated entreaties of, “Je veux un enfant,” as comedy, Karina’s delivery is far from tongue-in-cheek. Ultimately, it is the conviction of Karina’s screen presence which enables Angela to get what she wants, in spite of her boyfriend’s emotional immaturity. Though it might be a hair-brained scheme which finally convinces him to father her child, it’s the intensity of Karina’s performance which lays the emotional groundwork. Angela’s predicament speaks volumes of the persistent double standards which continue to plague young women. Having spent centuries inhibited by the pressure to reproduce, women are now often encouraged to liberate their sexual and professional self—not to let motherhood stand in the way of their ambitions. But if motherhood is one of a woman’s ambitions, childbirth is easily weaponized as an excuse to curtail their sexual and professional growth: too maternal to be desired, too busy to be invited to after-work drinks.

In the song ‘Zinnias’ from Clairo’s album, Sling, she sings:

Quietly, I’m tempted

Sure sounds nice to settle down for a while

Let the real estate show itself to me

I could wake up with a baby in a sling

Just a couple doors down from Abigail

My sister, man and her ring

On the one hand, it’s infuriating that the tension between performing femininity and motherhood still feels as pressing as it does in A Woman is A Woman. On the other hand, there’s something meaningful in drawing out those parallels today, charting the course we seem to be on, and the one we would like to be travelling down. For all the film’s contradictions and conventions, we should still remember Angela’s famous line, a French play on words and double-standards: “je ne suis pas infâme, je suis une femme” – “I’m not shameless, I’m a woman.”

A Woman is a Woman’s new restoration is on at Film Forum from February 7-20