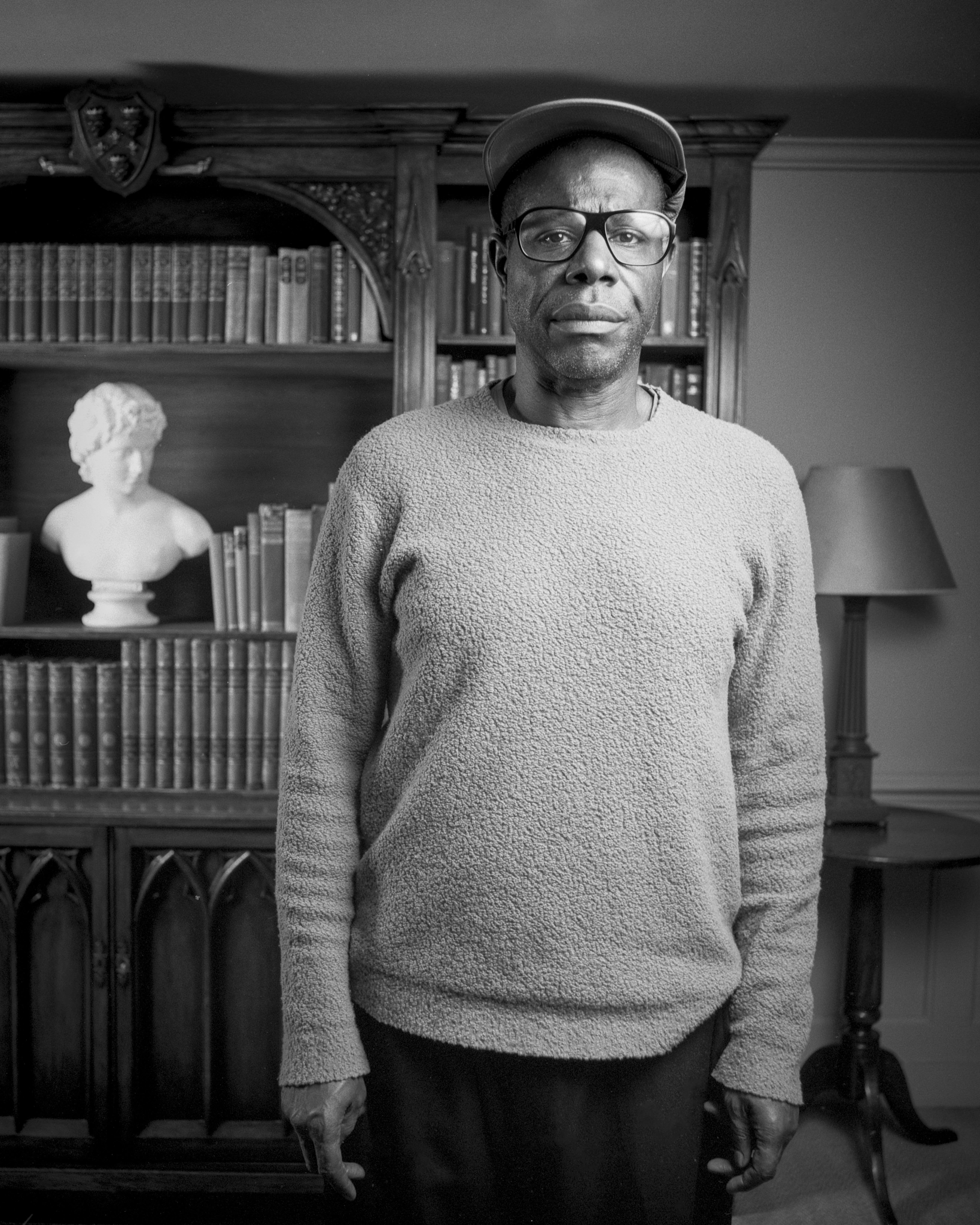

The acclaimed British filmmaker revisits an old London haunt with features writer Luke Georgiades to discuss his burgeoning legacy, his purpose as an artist, and what it means to blow dust off revolutionary images. Featuring photography by Robin Hunter Blake.

“I always feel the best wallpaper is books,” says Steve McQueen. “I like being surrounded by knowledge.” The acclaimed British director is sitting in one of the cosy meeting rooms of Soho’s Hazlitt’s Hotel, a Georgian-era townhouse that has been a regular haunt for the filmmaker for over 30 years now. “He knows this place better than anybody,” the concierge had told me with a smile as I checked into the room. Sure enough, McQueen, cool but casual in a pastel-blue fleece sweater and snapback, was now sitting in front of me totally assured with his surroundings. “I’ve stayed in every single room of this hotel,” he explains, shuffling across to the corner of the long antique sofa at the centre of the room. “I find myself at home. There’s something domesticated about it. I like its Englishness.”

Named after essayist William Hazlitt, the hotel has aptly become a sanctuary for some of the great thinkers, artists, and writers of the world, with the London-born McQueen being one of them. Busts and statuettes of Greek gods and heroes decorate each hall, chamber, and lampshade in Hazlitt’s, though lining the walls most abundantly, as the director points out, are shelves of literature. “I felt it deeply when I went to Amsterdam, because there were books everywhere. At an arm’s reach you could travel places. I like that kind of access to things. On the internet we have access, but with books, there’s curation. The editing has already taken place.”

While Amsterdam has become a home away from home for McQueen, London is never too far from his thoughts. “My perspective on Britain has helped by being away from home,” he says, as a concierge appears, placing a blue and white porcelain tea set on the table between us. “When you’re away from something you can focus on it better.”

“The first film I ever made was a journey home,” he recalls. “From Goldsmiths college to my house on a Super 8 camera. I wanted to find my way by looking through a lens. They didn’t have a film department at my art school, so I invented it. I used to go in, and I became friendly with this camera technician, and she’d loan me stuff.” Blitz (2024), McQueen’s latest, sees the auteur journey home once more, after some time spent traversing the canals and tulips of the Amsterdam cityscape for his 2023 documentary Occupied City (2023). Set during the eight-month period in the Second World War during which the Luftwaffe bombed London relentlessly, it’s only right that Blitz opens in chaos, with an image of a firehose writhing frantically like a dismembered Hydra head. McQueen picks up a star-shaped biscuit from a small plate on the table and pops it into his mouth, shrugging. “The symbolic nature of that image is that we’re not only fighting enemies, we’re fighting ourselves. The hoses were made out of canvas, not fully able to control the water pressure… all these mechanisms that were sort of inadequate and faulty. You get these situations where the firefighters are fighting themselves, with this image of a spitting serpent of the hose knocking someone out.”

Filmmaking is all about testing the temperature, McQueen tells me. The way he sees it, audiences are always ready to be challenged, provoked, tested—a cliff edge he’s been walking since the beginning of his career. He discusses his experience premiering Hunger (2008)—his debut feature about IRA member Bobby Sands’s famous hunger strike—in Belfast. “People were hiding under the tables and behind couches. They thought it was going to kick off. It was Bobby Sands. It was dangerous. No one had ever touched that subject.” On the plane back, a steward, recognising McQueen, refused to serve him. “The tensions were that high. But it was OK. The film became a barometer to show how far people had come up until that moment. It was important to put that film into the atmosphere and see what would happen.”

At the 2008 Cannes Film Festival, Hunger won McQueen the Caméra d’Or, an award highlighting first-time filmmakers with particularly bright futures. Five years later, he became the first black director to win Best Picture at the Oscars for his groundbreaking box office smash 12 Years A Slave (2013), an against-all-odds success story that altered the inner workings of Hollywood itself. “That was a big moment as far as my work was concerned,” he says. “There’s a before and an after 12 Years a Slave, because we know that because of that movie, people got movies made. Because it made bloody money, that’s all. Because it started a conversation about slavery that hadn’t happened before.”

A further decade on, McQueen’s cinematic mission still lies in the revolutionary image—a process of filmmaking some will have heard him describe as the act of “illuminating ghosts”. You can see it all over Occupied City (2023), the four-hour adaptation of his wife Bianca Stigter’s book about the long-lasting effects of the Nazi’s occupation of the Netherlands. In the film, McQueen imposes narration describing the past over footage of the city in the Present day. “A city can inspire you,” he says. “Walking around Amsterdam, though you couldn’t see them, it felt like living with ghosts. Surrounded by these histories, these stories, you can almost smell them, and hear them. Through the words [in the movie], you’d also be able to just feel their presence within the present.”

He stresses the significance that many of the images we see in Blitz are the first of their kind, though rooted in an unquestionable and, until now, overlooked truth of WW2-era London. George (Elliott Heffernan), the young mixed- race protagonist of Blitz—who must embark on a perilous adventure through the city in search of his mother Rita (Saoirse Ronan)—was himself inspired by a photograph McQueen found while researching his 2020 anthology series Small Axe. The image was of a black child at a railway station readying for evacuation. “I wasn’t just frightened of the bombs being dropped by the Nazis that could have killed him, but I was frightened of what people would make of him. For him, there were two wars going on.” Other sequences in the film radically highlight underground clubs where people of colour would find community, a reference to real establishments like the Shim Sham Club, known sometimes as London’s miniature Harlem. “The fact that so many movies have neglected the cultural diversity of London during that time is outrageous,”’ he says. “The images in this movie are revolutionary, you’ve never seen an image of a woman in an ammunition factory in a movie. You’ve never seen Mickey Davis—this man who was three foot six who was basically one of the architects of the NHS. That’s been ignored by cinema.” There’s a moment of quiet, save for the hum of the fireplace, as he takes a long sip from his teacup. “But hey, that’s their choice, and I made mine.”

During our conversation, McQueen returns often to the topic of the past and its cyclical relationship with the present. “They’re in the walls,” he tells me. “They’re not secrets. I’m showing people things that have always been there.” He’s referring to a chapter in his career that he describes as “a focus on history, but also the presence of now”, and of which he hints at Blitz as a bookend. Once he points it out, the theme begins to appear everywhere in his work, such as in Small Axe, about the struggles of the West Indian community in London between 1969 and 1982, the release of which coincided with Black Lives Matter protests taking place in London after the murder of George Floyd.

“I love using cinema, if I can, as a tool. That’s all it is. The lens is a fishing net. The microphone is a magnifying glass. That’s what it’s all about”

Similarly, though Blitz concerns itself deeply with a pinpoint moment in Britain’s history, McQueen maintains that his goal was always to infuse the film with the urgency of our present-day struggles, specifically the wars plaguing the nations and peoples in Gaza, Ukraine, and Somalia. He argues that by showing the reality of war through a child’s eyes, the hope is that we come closer to reaching a true understanding of its continued futility, a sobering feeling that McQueen has been in closer quarters with than most, having spent time with troops and locals in Iraq in 2003 as a war artist for the Imperial War Museum.

“This movie would have been relevant at any time,” he says. “Unfortunately, human beings never seem to learn, we’re always at war somewhere in the world. We’re also forgetting Somalia, which is happening right now and is always being forgotten, for obvious reasons.” He pauses briefly. “For racist reasons, let’s be honest.” As he says this, he leans towards the table where my phone sits recording our conversation. “Make sure you put that in print,” he instructs, before continuing. “As adults, at what point do we compromise? We pretend not to see, we go on with our daily lives. Most people in the West, I imagine, have never been in a war, therefore we get the information through the media, and thus, war feels very abstract. That’s why I wanted to feel this conflict of the Second World War in London—so people can understand that this happened here. Once people feel that, hopefully we can have a situation where people can start to connect to what’s happening in the world elsewhere.” In this way, he says, he’s never felt more useful as an artist than right now. “One needs to use cinema as a tool to change perspectives,” he says.“To infiltrate people’s minds and correct certain narratives… a certain numbness that we’re experiencing. I love using cinema, if I can, as a tool. That’s all it is. The lens is a fishing net. The microphone is a magnifying glass. That’s what it’s all about.”

“Cinema is like opera right now. It’s dusty. And that’s problematic. Film needs to be rock ’n’ roll. Film needs to be hip-hop. Film has to be whatever the avant-garde music is of now. And maybe we’re not giving the cameras to the people who deserve to have cameras: younger people. They’re the key. Some people are happy with it being like opera. Am I? Not really. You want cinema to be current. To be vital and valuable.”

If the microphone is a window into the celluloid soul, then imagine what music can do. As they shaped many of us, the pop sounds of his youth shaped McQueen, who cites ska-revival band The Specials as an inspiration, so it’s no wonder that music permeates his filmography almost celestially. Music runs through Blitz like an unstoppable force, touching the hopes, dreams, and open wounds of its central characters, acting as a spiritual shelter from the artillery reigning chaos on the city and its inhabitants. In the film, George’s relationship to his mother and grandfather (not coincidentally played by Paul Weller, member of English rock band The Jam) is tied deeply to a nostalgia-dyed memory of the three singing ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’’ around the family piano; a later dream sequence sees George wandering through the tunnels of an underground shelter, following the sounds of music until he emerges at his local at Stepney Green. “Music is what we are,” McQueen says. “It’s food. It’s being in love. During the war, it was ‘’Ain’t Misbehavin’’ by Fats Waller, ‘Oh Johnny’ in the Café de Paris, people playing early skiffle music in the underground shelters, or Rita [Ronan] singing ‘Winter Coat’. These sounds that perfume the air give people courage.”

And then there’s Lovers Rock (2020), the mention of which causes McQueen to light up. Named after the reggae subgenre which found popularity in mid-70s London, the second episode of his Small Axe series is a joyful musical odyssey through a single night of romance at a West London reggae party, soundtracked to the likes of Janet Kay, The Revolutionaries, and Carl Douglas. Upon release, the film became an instant standout in the anthology, and remains one of the best films of the past decade—period.

I ask McQueen why he thinks the film has become such a fan favourite, and his response unravels slowly, eyes closed tightly and fingers pressed to his temple, as if he’s asked himself the question many times over before and hasn’t quite settled on an all-encompassing answer. “Lovers Rock plays like a record,” he says. “I know people who put it on in the background and then live with it. It’s a pulse. It’s circular, like a seven-inch. Small Axe is an album, and Lovers Rock is the single.” He recalls a moment at the New York Film Festival premiere of the movie, an outdoor drive-in screening that saw attendees getting out of their cars and dancing along as the film played against the backdrop of a New York summer night—a brief respite from the claustrophobia of the pandemic. Back home in London, still under Covid lockdown, families took similar solace in the film, crowding around their television sets and dancing to Janet Kay’s ‘Silly Games’ in their living rooms. Another instance of a McQueen movie arriving at a time when the populace needed it the most. “Cinema is like opera right now. It’s dusty. And that’s problematic. Film needs to be rock ’n’ roll. Film needs to be hip-hop. Film has to be whatever the avant-garde music is of now. And maybe we’re not giving the cameras to the people who deserve to have cameras: younger people. They’re the key. Some people are happy with it being like opera. Am I? Not really. You want cinema to be current. To be vital and valuable.”

McQueen doesn’t watch his films back often, but still, I wonder aloud whether he ever finds himself plagued or encouraged by the prospect of legacy. “Dude, I’m young, I’m fifty fucking five years old, and you want me to think about a legacy?” he says, half playfully and half genuinely horrified. I suggest that his body of work thus far has already made more impact than many filmographies do in entire multi-decade careers. His reply reflects his ethos perfectly—a vision concerned with truth, collaboration, and the possibility of cinema as a boundless medium. “I’ve made a lot of stuff in a short number of years,” he says. “People tell me I shoot fast. I’m not aware of that, because I’ve never known any other way. I just want what I want. I’m not interested in a career, I’m interested in film. Cinema is thrilling. It’s exciting to be on a set, to work with actors, and art departments, and DPs, and wardrobe. Because there’s possibility.” He pauses, finishing his thought. “Legacy? No. I’m just getting started. I feel like I’m moving into third gear, with five more to go. Blitz was the bookend to an intensified six-year journey—starting with a photographic artwork I made which was exhibited in Tate Britain called Year Three, and including Small Axe, the documentary Uprising (2021), the artworks Sunshine State (2022) and Grenfell (2023)—focusing on time and place in London, uniting the past and the present, but,“ he adds, “there’s still a long way to go yet.”