Shakespearean actor Dame Harriet Walter talks about iambic pentameter, bad mothers, and playing her most evil character to date.

“Are you one of those people who knows a lot? Or are you remembering what you did at school?” Dame Harriet Walter DBE, acclaimed RSC actor, five-time Emmy award nominee and winner of a Laurence Olivier Award, is asking me about my relationship to Shakespeare. And I find myself telling her, exactly as I promised myself I wouldn’t, about my Year 6 performance as Demetrius in a simplified version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As a tall 10-year-old with little acting talent at an all-girls school, I was made to play one of the male lovers, and the least important one at that: it is his rival Lysander who gets the iconic pentameter: “The course of true love never did run smooth.” During rehearsals, with time to kill, I worked out that of all the lovers in the comedy, Demetrius is the only one to end the play still under a spell. His love for Helena remains an illusion. In the wings, I couldn’t help but feel sorry for poor Demetrius, and for myself, in the scratchy yellow toga.

I had put that memory firmly into a mental box labelled ‘normal?’ until I read She Speaks! (2024), Walter’s recent book about Shakespeare, in which she makes the same observation about Demetrius. The book—somewhere between fan fiction and revisionist history—gives voice, by way of imagined speeches, sonnets, and dialogue, to the Bard’s female and gender-fluid characters. “There are some strands and themes that I’ve come up against a lot—with regards to gender, in terms of plot and also just how much stage time you get, there’s a lot that’s been brewing and bubbling inside me,” says Walter, a cup of Earl Grey steaming in front ofher. We are at a branch of Gail’s in West London, the night after Halloween. Walter, 74, lives nearby, and the middle-class haunt is her go-to spot for interviews, allowing her to turn up, as she points out to me, with a wiggle of the foot, in her “flip flop shoes”. Walter’s voice is sweet and granular, with a coquettish quality that foils the severity of her dark eyes and short, slick black hair. With the intensity of a stage whisper, she describes a list of Shakespearean characters ranked in order of how many lines they have: “There are only 15 female roles in the top 100, and Rosalind [from As You Like It] is the biggest female role at number 15, so there are 14 male roles bigger than hers.” And, of course, as Walter points out in her introduction, if she were to time travel to the Globe Theatre in the 1590s and early 1600s, Shakespeare’s female parts would all be played by young boys anyway. I wonder what they would make of me, a schoolgirl in a toga, 400 years later.

The idea for the book came when Walter was invited to write a new speech for Gertrude by the Shakespeare Schools Foundation. In ‘What Gertrude Wanted to Say’, the actor gives Hamlet’s mother a chance to defend herself against her son when he “harangues her in her chamber and asks how she could possibly love Claudius.” Walter’s riposte dares to imagine Gertrude, a menopausal mother, as a sexual creature: “Overtly loving, spend whole days in bed/Surfeiting those appetites so long unfed.” The book is alive and expansive with Walter’s deep knowledge of Shakespeare’s plays. (When someone says “I barely know Pericles,” they clearly know their stuff.) Walter creates new dialogue for icons such as Desdemona, the Three Witches, and the Dark Lady (the anonymous recipient of Shakespeare’s many sonnets) as well as small supporting parts such as Charmian (Cleopatra’s handmaiden), Hermione, Imogen, and Juliet’s nurse. She also imagines new scenarios, such as a chorus of Shakespeare’s motherless daughters (Portia, Isabella, Hermia, etc). “It all came gushing out rather easily,” says Walter. “I’d wake up with a line in my head that I’d need to follow through.” She highlights how Shakespeare perhaps ignored his female characters’ motivations. “She seemed to have a very alive, darting, questioning mind,” she says of Cressida. “So why was she so quickly unfaithful to Troilus in the camp? [Shakespeare] wasn’t looking at that story through her eyes. He started off on her side and then abandoned her.”

Walter’s first professional performance of Shakespeare was as Octavia in Antony and Cleopatra in repertory, then in Hamlet as Ophelia alongside Jonathan Pryce. That was at the Royal Court in 1980 and over her career she has played no less than 21 different Shakespearean roles. Growing up in London—her uncle was the famous actor Christopher Lee—she turned down a spot at Oxford University to study drama at LAMDA, swapping modern languages for the carnal pulse of iambic pentameter. “The rhythms get into your skin, if you’ve sat with Shakespeare’s language running through your head for eight shows a week for a year, it sort of runs in your bloodstream,” she notes. Walter credits acting with teaching her to write—She Speaks! is Walter’s fourth book about the Bard, the others being Clamorous Voices: Shakespeare’s Women Today (1988), Macbeth (Lady Macbeth): Actors on Shakespeare (2002), and Brutus and Other Heroines: Playing Shakespeare’s Roles for Women (2016). “A lot of actors can write. I’ve worked with some of the great writers of our culture. It means you can spot a well-made sentence when you see one,” says Walter. Yet her approach to the craft is theatrical. “I read everything out loud in my head. I love the sound and feel of words. Some people can skim, but I have to sound it all out and hear the balance of the sentence.”

“I could hear every word. There was stuff in the play I hadn’t paid attention to before. And you think, ‘My God, nobody has described the human condition more beautifully and understandingly than this man 400 years ago.'”

Harriet Walter

Walter’s career as a stage actor was maturing as a new era for Shakespeare was born. In 2016, the Donmar Warehouse in London staged Phyllida Lloyd‘s’s trilogy of Shakespeare plays set in a contemporary women’s prison—Henry IV, Julius Caesar, and The Tempest. Walter appeared in each one. While now the idea of contemporary productions with “fax machines and offices”, as Walter puts it, along with gender-and race-blind casting is the norm, then it was still radical, opening up new roles for female actors, and in turn finding Shakespeare new audiences. “It wasn’t just that we were women, it was that we were unusual women for those parts,” recalls Walter. “That’s the whole exercise of drama, that we sit and look at people on stage pretending to be other people, and we go, ‘That could be me’. Whether it be women or older people, or young people, or gay people, or fat people, or thin people, you block out a lot of people by narrowing down who is allowed to be the hero.”

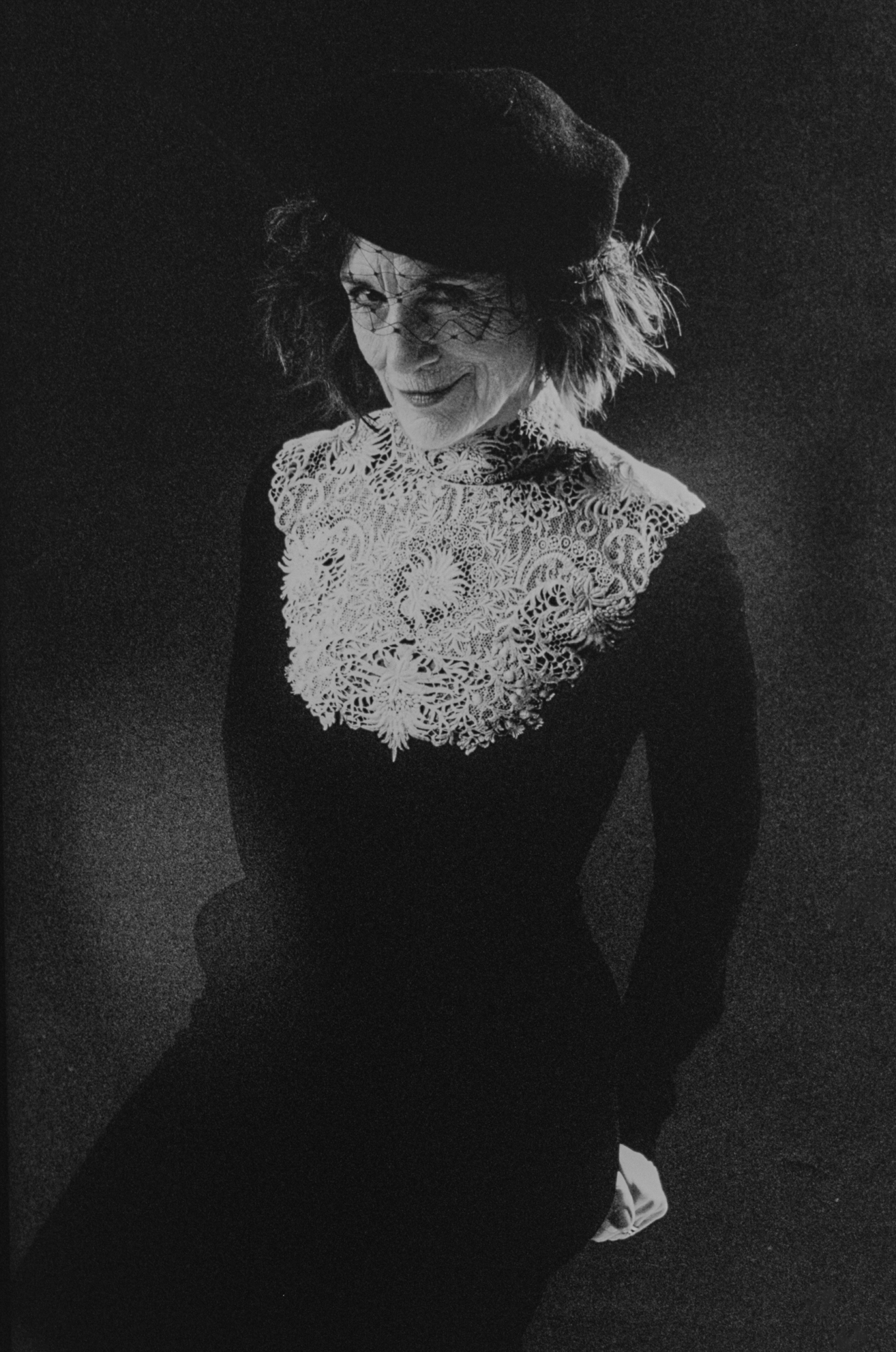

Harriet Walter by Laurence Hills.

Fashion director: Marcella Martinelli @marcellastylist at Arlington artists

Makeup: Justine Jenkins et al. beauty @etalbeautycollective

Hair: Sven Bayerbach at Carol Hayes Management using Drybar

Shot 1: Awon Golding Van Doren grosgrain ribbon headpiece www.awongolding.com

Shot 2: Awon Golding: Montmartre veiled wool felt beret

www.awongolding.com

Dior Cupro velvet long dress with lace collar

House of Dior www.dior.com

Sole Bliss black suede boots solebliss.com

I confess to Walter that, despite my promising beginnings, today I find Shakespeare a challenge. “Each time you go to a play, it’s a risk. It’s expensive and you don’t know if you are going to enjoy it or not. I’ve often guiltily thought that Chekhov and Shakespeare are more fun for the actors than for the audience,” she agrees. I breathe a sigh of relief. “But you can understand Shakespeare if you want to. It’s not double Dutch. If you don’t know a word, look it up,” she adds, with a slight tut. Maybe such slowness could be a corrective to the Tik-Tok fuelled immediacy of our times, I suggest. Walter agrees that while for her generation Shakespeare’s biggest barrier to entry was a “class block”, today it is concentration. Yet she goes on to describe the many letters she has received from young people who, even recently, have gone on school trips to see Shakespeare and left transformed. “Something happens to them as an individual. They’re converted in a certain way.” Shakespeare still manages to be transformative for Walter. She describes a recent production of Othello she watched at the RSC. Set simply in traditional costume, it still had the power to feel contemporary, ironically, as the focus was the language. “I could hear every word. There was stuff in the play I hadn’t paid attention to before. And you think, ‘My God, nobody has described the human condition more beautifully and understandingly than this man 400 years ago.'”

In the final chapter of She Speaks! titled ‘Prospero’s Pronouns’, Walter describes the feeling of getting older as an unsexing: “I found myself in quite a new place, neither man nor woman but person; an aging person.” I find the moment poignant, as much for its vulnerability as for the truth it carries about gender’s fluidity. I ask her to expand. “I never know if it’s sex or gender,” she admits. “But I suppose I was thinking about identity and the notion of, do you wake up in the morning feeling female or male? It’s only when you go into the street that you’re reminded of what you are to other people. Inside, you’re much more fluid. I am. And I didn’t really realise because I never felt super feminine. And I didn’t feel I was a masculine woman either, but I don’t feel internally male or female. I’ve lived my life as a woman, so I have the experiences of a woman, but the ‘me’—the essential Harriet Walter inside me—is not either thing.”

So far, ageing has rather suited Walter. In her 60s and 70s, the actor has enjoyed a highly successful third chapter, particularly in television (she acknowledges that theatre kept her busy during the “tricky years” of her 40s and 50s). Her recent credits include Ted Lasso, Killing Eve, This is Going to Hurt, and Wolf Hall, cementing a reputation for playing slightly ridiculous, imperious mother figures. Particularly since her own mother’s death, however, she feels conflicted at playing such roles. “I think we’re very unfair to mothers. So I feel very mixed up when I get asked to play negative portraits of them,” she explains, referring back to her defense of Gertrude. “There’s an infantile dependency on mothers. Maybe if I looked at the world from her point of view, I’d see something else.” In perhaps her most Shakespearean role to date, Walter played Lady Caroline Collingwood, the hilarious ex-wife of Murdoch-inspired media mogul Logan Roy in HBO’s Succession. Her funniest moment includes asking guests at her daughter’s wedding how long they give the marriage. “I thought, if I had to spend an evening with her we’d have quite good fun,” says Walter.

The actor’s latest role might be her darkest yet. In Channel 4’s Brian and Maggie, directed by Stephen Frears, she plays Margaret Thatcher opposite Steve Coogan as Brian Walden, the political interviewer whose 1989 televised interview with the Prime Minister following the resignation of her chancellor Nigel Lawson was the first domino in her downfall. “I was in the middle of doing The House of Bernarda Alba [Federico Garcia Lorca], and I thought, why am I playing all these martinets?,” says Walter of being offered the role. “She’s not my favourite woman, but it’s enticing to get under the skin of a character who has got such a steely front. She must have a beating heart in there, you know?” With notes of a love story, Brian and Maggie depicts Thatcher and Walden’s close rapport prior to the “betrayal” of the interview, built on a shared feeling of being grammar-school outsiders in a Eton-run world. “She had an affinity to him and he brought out a side of her we don’t usually see. Humanising Margaret Thatcher has not been my mission in life, but the fact she was a woman was so irreverent in the choices she made and the persona she adopted and wouldn’t drop,” explains Walter. “She had to step into this clubby, establishment network, which took undeniable guts. Sadly her motivations were not the same as mine.”

In her real life, Walter is on the side of the many, not the few. “I’m quite gregarious, easy to get to know and hang out with. I’ll only be snooty if people are rude. And then I will come out all Lady Caroline on them,” she says. Politically engaged, Walter has used her platform to speak about the migrant crisis and Ukraine, as well as the ongoing war in Gaza, signing an Artists for Palestine letter calling for a ceasefire. “I don’t want to set myself up as a brave revolutionary activist, because I’m not, but I’ve lent my voice to certain causes, and I’ve turned up,” she notes. “There’s a general wash of human justice that I stand for, really. If I wasn’t such a well-known face, I’d probably do more, to be honest.” I feel in awe of Walter. Her slightly unconventional trajectory is refreshing to hear about—she married for the first time in her 60s and has never had children, which, she admits, adds to feelings of not being “typically female”. I wonder what Walter would be doing if she hadn’t pursued a career on stage. “It’s funny, isn’t it? Because I could have written but I didn’t know I could write until I acted,” she replies. “I’ve always said I’d have been a taxi driver because I’m good at finding shortcuts and I’m quite nippy in traffic.” A Dame as a cabbie? It’s a part Walter seems destined to play.

Harriet Walter by Laurence Hills.

Fashion director: Marcella Martinelli @marcellastylist at Arlington artists

Makeup: Justine Jenkins et al. beauty @etalbeautycollective

Hair: Sven Bayerbach at Carol Hayes Management using Drybar

Shot 1: Awon Golding Van Doren grosgrain ribbon headpiece www.awongolding.com

Shot 2: Awon Golding: Montmartre veiled wool felt beret

www.awongolding.com

Dior Cupro velvet long dress with lace collar

House of Dior www.dior.com

Sole Bliss black suede boots solebliss.com

Foot Note

Oh, These Men, These Men!

By Harriet Walter

Unique we were, Othello, you and I,

An ‘us’ we formed together to defy

All preconceptions, jealousies and fools.

I chose you, did the running, broke the rules.

Remember how we whispered by the sea,

Remember how we prized our secrecy?

How equally we felt that loving flood

That forced down dams and mingled in our blood.

Magnetic pulses folded into one,

You were my puma, I your spreading swan.

Would I dismantle that for Cassio?

Who got to you? That’s what I want to know.

How easily the monster took its hold

In your sweet fertile soil and fearful soul.

Your wartime courage drained, you lost your head

And now believe the thing you most do dread.

I thought you knew me, lover, wife and friend.

Your treasured trust I never would misspend.

But poisoned words fed by a fellow man

Convince far more than woman’s actions can.

Emilia hears my song and feeds my flame,

And teaches me that all men are the same.

I catch my breath, succumbing to your might.

I just woke up as you put out my light.