I ride shotgun in a little Renault, bombing it down the arse-end of Galway. Past a rain-drenched castle, manically trimmed trees, and a bit of plywood cutting across 80 kmph roads like vengeful shrapnel, my girlfriend Etta (who wants you, the reader, to know she is driving) snaps.

“My love,” she asks sweetly, “where the fuck are we?”

I have no idea. We’re on our way to Mee’s Pub in Kilkerrin. A village in the middle of nowhere, following the route known as Graveyard Road. We’re on our way because the rose-faced publord Luke Mee—already something of a local tycoon—has realised a brilliant idea: taking the pub, JJ Devines, from The Banshees of Inisherin filmset then installing it, brick by brick, inside the smoking area of his own pub.

It’s like an Irish human centipede, I think. Or a pub-matryoshka doll. From the crags of a forest river, a low-res poster expands into view. Are we getting closer? The sign is no help. ‘SAY NO TO TURBINES’ it reads back, bright and red. Etta breaks, and asks me, once more, where the fuck we are again.

“Some kind of void, I suppose.”

A white-walled town, where the smell of manure and daffodils is overpowering, appears round the drizzly noon corner. Kilkerrin is one of those places which is really just a straight road and seven houses. Mee’s Pub, the name spelled out in bright paint, is it’s beating heart. “I’m getting more Stepford Wives vibes,” Etta says as we close in. We park our car behind the church three yards away.

Beyond a wheezing door, the pub is lit by cosy fairy lights. RTÉ plays the local news behind the bar. About six or seven people sit in the pub’s three large tables, filling the room with voices that are musical even by Galway standards.

“It’s actually nice,” I say, by instinct. I walk to the bar, and peer at the glass window by the door at the end. I can see the faint yellow paint of the Banshees film set tucked behind the smoking area. Sheepishly, we return back to a long bar stool while the barmaid sits up from a table of regulars to calmly serve us.

“A Guinness for me please,” I say. “And a white-wine,” Etta adds. The barmaid pours with a bright smile.

“Do you have the Banshees set in the back there?” I ask quickly.

“Yes,” she says.

“That’s insane. We drove all the way from Galway city to see it.” Etta gives me a quick nudge when I say this.

“Are ye serious?” she laughs. “I’m a film journalist,” I continue, “I’ve heard so much about this place.”

“Ah grand, yes,” she smiles again, setting our drinks down. “I’ll show it to ye now.”

I’ll later learn that the sunny bar maiden I’m speaking with is no other than Cathleen Mee—the owner, Luke Mee’s, sister. As we move to the empty smoking area, I realise she has the air of someone from Banshees: a happy, easy lilt that’s existed like a beacon through Ireland’s strangest moments.

We follow the pub’s door, past a metre of astroturf and wet outdoor tables, to the film set: the haunt for Colin Farrel and Brendon Gleeson’s troubled characters. It’s unmistakable. The thatched roof set under a metal shed fits like a perfect snug; the timber walls are crinkled; the yellow paint shines in the drizzly smoking area. 1842, reads the sign outside. Inisherin.

“I’ll put on the lights now,” says Cathleen as we huddle into the pub-within-a-pub.

The single room glows up. I spot, immediately, the far right table that Farrell and Gleeson hunched over for so much of McDonagh’s brilliant comedy when they discussed snipping fingers.

“Do you get lots of people like us?” I ask. “Tourists?”

“All the time,” says Cathleen, still bright and lilting.

You can’t help but laugh at every prop inside. A window is lit up with the same stunning cliffs from the movie’s Achill islands. There’s an old clock, clay pots of Galway whiskey, an advert for Guinness. The attention to detail is stunning. “We watched the film again and again,” says Cathleen, floating through the set, “to get it all right.”

The smiling is infectious. She’s laughing, almost, at our amazement.

“Do you do any lock-ins here?” I ask.

“The night we opened it. Ah, that was last May or June. Stop, Jaysus. Now that was mental.”

“And how long did it take to get it over?” asks Etta, looking around.

“It took Luke about three or four months. Maybe five. Did it with a single trailer from the isle.”

“It came out well,” Cathleen says proudly.

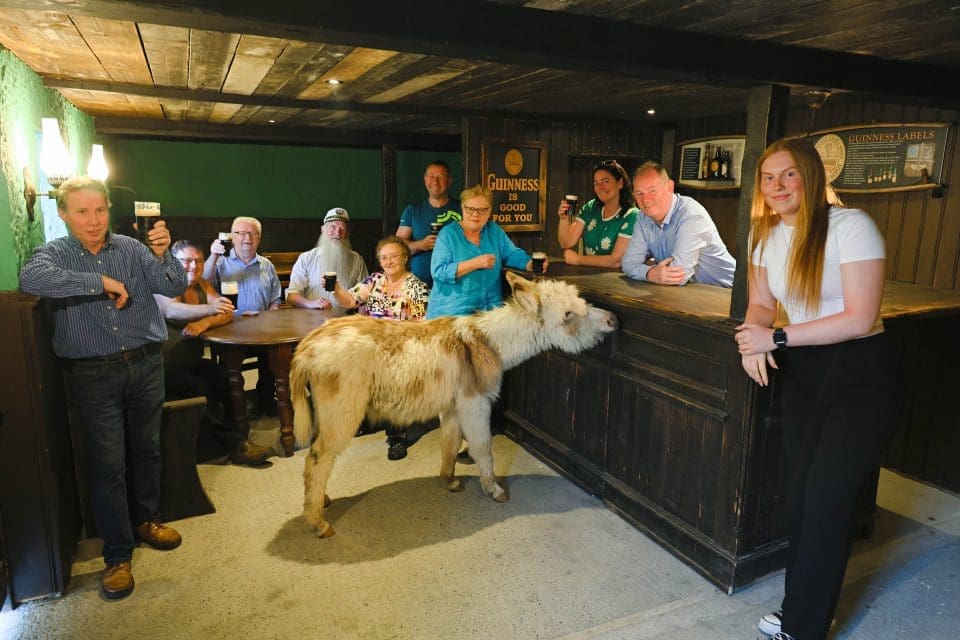

“There’s no miniature donkey is there?” I ask.

“He only comes out for photos and that,” says Cathleen. “It’d be cruel to have him out all the time.”

A slim lady in a dark suit pokes her head inside, to tell Etta she’s left the lights for her car on. We move back to the main pub as she darts out, and I sit down in front of Cathleen for another Guinness.

“You did such a good job,” I keep repeating. “Have many of the actors come to see the pub?”

Cathleen pours my stout again. “None. Not yet. I know one of them actually emailed. You know the funny guy that was on it?”

“Barry Keoghan?”

“Ah, not him. The fella that was working in the bar. He’d like to pop in.”

“He should,” I say.

“And of course there’s Taylor Swift,” says Cathleen, recalling the pop-star’s viral Tweets that promised she’d pay a visit. “Supposedly,” she smiles slyly. “She’s actually coming to Ireland in June, singing.”

“She must come,” I say.

“She might. I suppose there’d be queues down from here to God knows where.” Cathleen settles my pint down on the bar. “Collin Farrel! He’s the one I want to come. I don’t care much about the rest.”

I laugh, then sip. “This is a nice Guinness.”

Cathleen moves on to the regulars, and I take in the sounds of an Irish pub: the gossip, the clinks of glass. There’s a warmth to Mee’s pub that comes from good memories soaked into the walls; the kind of pub that effortlessly beckons you to have another round.

I sit back inside the Banshees pub when Etta returns, the two of us taking pictures like schoolchildren.

An old lady in a blue jumper invites herself back into the Banshees pub, cigarette in hand. Her name is Grania, and her voice has the same lilt as Cathleen, one that rolls like the wild hills surrounding this small village: “Do you want a photograph of you taken from behind the bar?” she asks. Of course we do.

Afterwards, we move to the astro-turfed garden to smoke. Grania tells me “she wasn’t being nosy now.” I laugh. “I was one of the people who helped paint it,” she explains proudly.

She chokes out her version of the story out between her smoke. “They bought it out in Ackle,” she says, pointing at the yellow walls, “and that was all covered up.” A church bell begins to ring behind us. “They got it during the pandemic so no one really knew what was happening. Aileen and myself and Cathleen and a few others, we let the men do all the work, and were doing all the painting. Then the seats. The benches. It was two weeks in June and that was our summer,” she explains. “ It was lovely. ”

Based on my phone call the next week, it doesn’t quite gel with Luke Mee’s (that’s the pub landlord) version of events. Luke was so secretive about the construction he tells me, he didn’t even inform Cathleen—ostensibly so “no one would tell lies to the customers.” I don’t know how long Cathleen, or the regulars, could have believed such an outrageous fib.

But as Grania speaks to me, I realise that Aileen—the suited lady who had told Etta about her car—is now shimmying over. “We were down here from about ten, weren’t we Aileen?” Grania asks. “That was the best summer we ever had. We’ve never had any weather like that,” Aileen continues. “Oooh it’s a shit summer now,” Cathleen coos.

“We were testing the cocktails every evening back then,” says Aileen. “I’d bring down sausages every morning,” says Cathleen, “and it got so hot we’d have to have ice creams in the evening. And then when we finished—we had to have a pint, y’know,” she laughs.

Whilst the renovated film set looks picture-perfect, they’re getting used to the guests. A girl from New York came down the other day, the smoking ladies tell me. Then there was a marriage across the road that ended with photographs in the pub. Even a christening recently. Aileen pulls out another cigarette. “We had a busload of Yanks come in today,” she says, slightly forlorn.

While there could be favourites among the growing visitors to this small village, it doesn’t seem we’ve made a bad impression. So how did the owner get the idea in the first place? “Oh it was some genius,” Cathleen says. “His wife thought he was mental,” says Aileen, “his sister thought he was mental too.”

Luke’s wife and her sister are from the Achill islands: the largest island off the coast of Ireland. Luke would go there as a child for summers, and even met his wife in the islands in 1955. The Achill islands are a popular film set, and in a country where rumour outpaces fact, all of Galway knew Banshees was being filmed there. Luke would even visit the film set during the filming of Banshees, and remembers the sheer beauty of the movie’s pub. When the movie had wrapped up, Luke’s brother, who had worked on the production, had asked to keep the pub in the shed of his house with an instinct that feels akin to hoarding (Luke’s brother-in-law argued it was for the value of the timber). And when Luke saw the media frenzy for Banshees during the Oscar and BAFTA runs, his mind began to wander: “Tis a pity, they’d be gone for well over a year,” he’d tell me on our later call. “That pub it’s an awful shame, it’s a tourist attraction.”

When Luke learnt his brother-in-law was hoarding the pub, the two men decided to do each other a mutual favour: Tom sold him the pub for free on the condition he’d get it out of his way. Luke rallied four friends, and hired a truck to transport the different sections of the set into his pub.

“We were like elves,” he’d tell me later. “Everyone thought it was a landfill until it was resurrected.” Calling it a good bit of paddywhackery and Irish madness, Luke rounds off our call with a kind of homily: “One man’s rubbish, is another man’s gold. It was a labour of love, so.” When they unveiled it, even he was shocked: “We didn’t expect it to turn out so good.”

As I hear half of this story from Grania, we look at the shining bright pub-within-a-pub with amazed eyes. “Well it sounds like a mental idea,” Etta says.

“Doesn’t it?” Aileen agrees with pride. We stand and look around at the smoking area. I realise the ladies are looking at it with scorn.

“There were tents in between here,” goes Grania, describing Luke’s unorthodox measure to cover up the construction. “A great atmosphere,” says Aileen. “Like a gazebo.” They look at the slightly brutalist new metal box that makes up the new shelter for smokers in between Mee’s Pub and Banshees. “I thought it was a men’s urinal,” says Etta. “Ah there!” says Aileen. “Now I love the way you said that. I’ll use it for my argument.”

Aileen finishes her cigarette. “Let it be said: we weren’t consulted for that part.”

Grania has gone in to get a book. Although he’s not here, I’m told Luke, the man behind the pub-within-a-pub, “does have some brain. Some genius.” Hungry, we’re told we can bring food in from the local Chinese and as I pop out, I shake Grania’s hands. She tells me they’re bloody freezing.

As we eat our curry chips—it’s the specialty here—Grania comes up to sit with us again. She wants to know where we’re from, if we like it here, and quickly, slides into telling a hundred stories of her own: a wedding that was no craic, the pace of life here, the surge in business. Her eyes are fogged up by her glasses by the time the locals pull her away (“I’m not nosy! You are!” she protests). I dust the powdered curry from my frock. Etta looks to me.

It’s time for us to go. I’d just explained, in the quick bursts with Grania, my mixed Irish heritage. I thank Cathleen for the tour and ask her what they’ll be doing for Paddy’s Day next week. “Oh they’ll be no parade, sure,” she says. “But some music in the back. A little fiddle.” Then, without a pause, “Diddlee-deee.”

As we go to say goodbye, I smile at Grania, who sits by the TV watching a game of rugby. It’s the big Six Nations game tomorrow, the classic England-Irish grudge match. “You’ll be supporting Ireland, won’t ye pet?” she asks. “Of course, of course,” I smile, “especially with a pub like this.”

Mee’s pub is busier now, happy and loud. There’s another wave of conversation, like a volley, as the young drinkers pour in.

The TV flickers a tease of the match.

“Up Ireland!” goes Grania, her hand raised high. “Up Ireland!” I shout back.

“Up the Banshees!” goes a pair of boys—lads I’d never spoken to, with a final roar.