“I’m feeling quite relaxed here.” For a man who is so in demand, Willem Dafoe has a touch of zen about him. When we meet at the Marrakech Film Festival, where he is a jury member, the actor seems in good spirits, on a soft work break after a prolific year in which he starred in seven films. It’s a cracking list, with some bizarre, creative character names. In Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron, he voices the Noble Pelican. In Inside, he is the art thief simply known as Nemo. For Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City, he portrays revered acting teacher Salzberg Keitel (which sounds like a Dr Oetker cake mix company). And in Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things, based on the novel by Alasdair Gray, he is Dr Godwin Baxter, a disfigured scientist who revives Emma Stone’s Bella, and takes on the role of her adopted father.

“I’ve been busy,” he laughs. But being busy isn’t the half of it. Dafoe continues to seek out and work with the most distinctive independent filmmakers, usually on the most offbeat titles, while also having a reputation as a mainstream Hollywood star (speaking of stars, he has just earned his own on the Walk of Fame.)

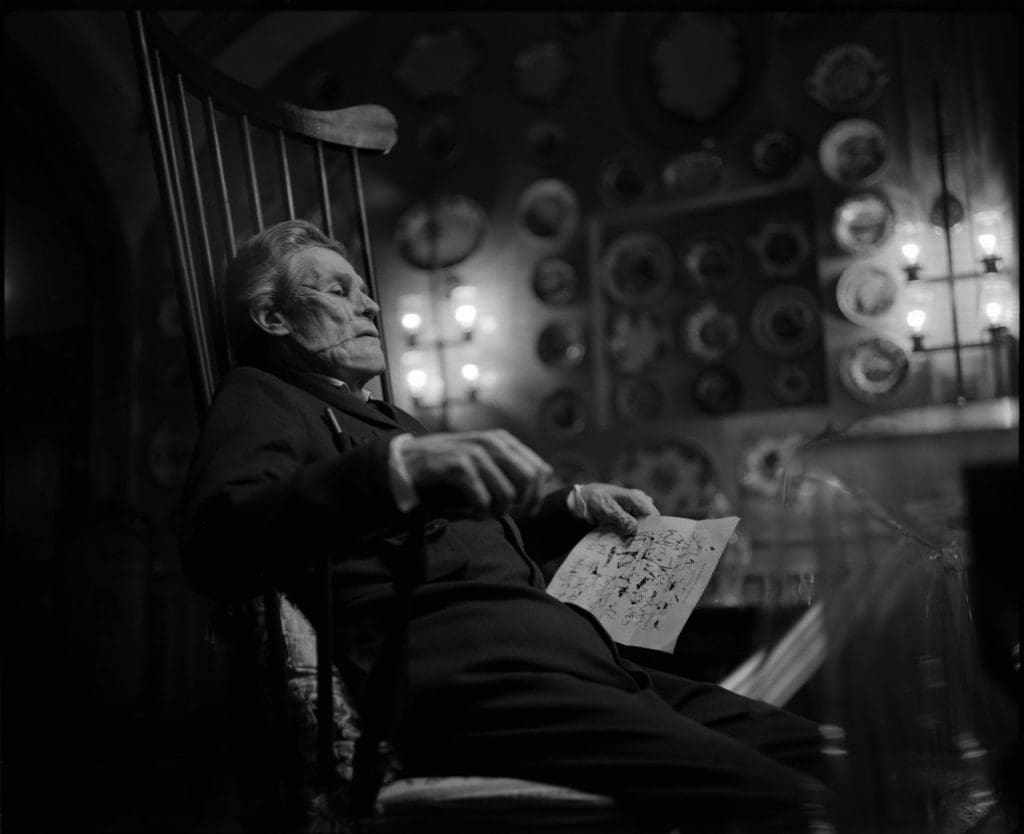

But he is promoting Poor Things, and with the film’s recent Golden Globes success, his performance has been rightly praised: Godwin Baxter is a kind character, a man torn between scientific rationality and his paternal affection for Bella. For the role, Dafoe wore a monstrous prosthetic mask that makes the Elephant Man look like Marlon Brando, subverting expectations when he becomes the only male in the film to love her unconditionally. But Dafoe is bashful when I praise his performance, and deflects—as he tends to do throughout our conversation, and not only in regard to Poor Things—onto the great work performed by his colleagues. In this case, it is Yorgos and the art department. “Yorgos’s world was already so complete,” he tells me. “So, it was up to me to play a part in his world. The make-up is a beautiful mask. You sit in a chair for many hours, and you see yourself disappear, and then someone else emerges.” It’s easier to pretend when the man in the mirror is another man, he explains. “You have to jump on that opportunity,” he adds.

Although he plays down his talents, there’s a reason why Dafoe has been cast in Lanthimos’ next film, as well as in Robert Eggers’ adaptation of Nosferatu. He is a distinctive actor with one foot in the mainstream and another in arthouse cinema, who has been sought by the most innovative filmmakers of every generation, including William Friedkin, Wes Anderson, David Lynch, Werner Herzog, Katheryn Bigelow, and Oliver Stone. But he has never really been associated with any of them in particular, instead sampling their magic and moving on to work with something, or someone, new, and consequently becoming the most memorable part of the over 150 projects he has starred in. His repeat performances in Lanthimos’ and Eggers’ films show a new side to how he approaches his work; he becomes a familiar, recurring face in their troupe of actors. Is this a journey he is conscious of at this stage of his career? “Yes,” he says, with a smile, as though it were the most obvious observation. “Because when you work with someone like Yorgos or Robert, and you realise that they get you, there’s a pleasure and sense of security that makes you want to be a part of that work. I also love to be a part of someone’s film vocabulary. They’re invested in you, as an actor, and because they’re giving me different roles to play with each project, I know that they’re not trading on the persona people have created around me.”

Dafoe is very conscious of his image with moviegoers and the press; his numerous roles as oddballs or villains; his striking visage, the mesmerising, menacing stretch of mouth and cheekbones, the R-rated controversies in the past, and he enjoys subverting this image through his characters. But his response also betrays a true cinephile, who considers who he chooses to work with as part of a bigger picture, his legacy: “It’s like being a colour in an artist’s palette,” he adds, “and with each filmmaker, you represent a new colour. From a historical standpoint, if they’re a director you admire, you get to enter into their iconography. That’s the magic feeling.”

Sometimes, there’s a level of artistic corruption and fatigue that comes from success…young people don’t have that. They have energy…a sense of hope.

Willem Dafoe

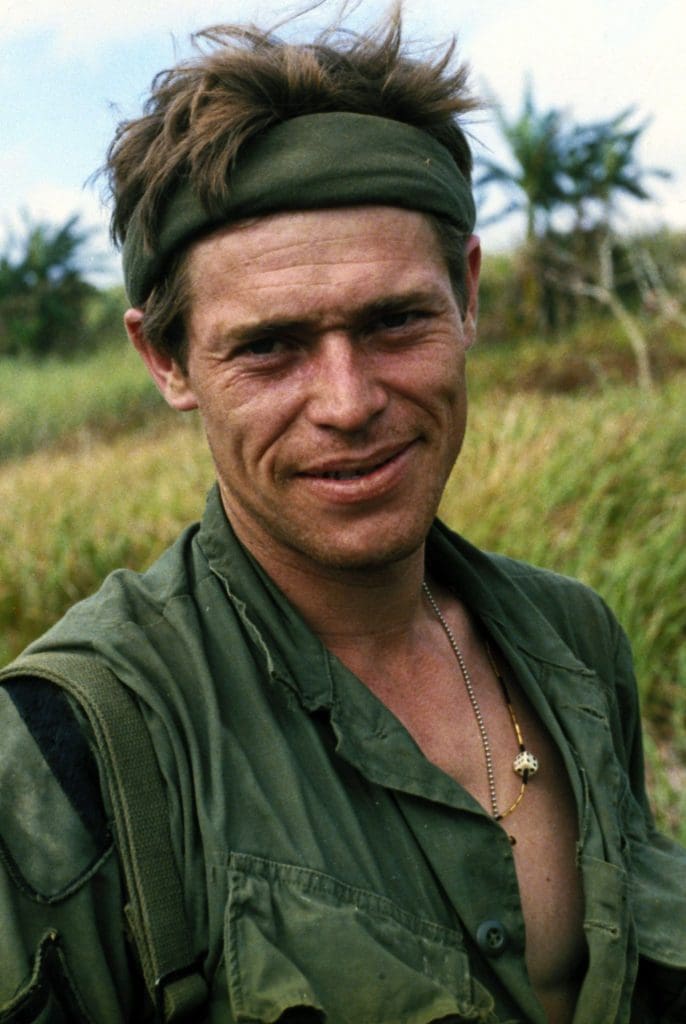

Apart from working with established filmmakers, he continues to star in lower-budget flicks by emerging directors. At the 2023 Venice Film Festival, I was surprised to see Dafoe in Olmo (son of the artist Julien) Schnabel’s terrific independent film Pet Shop Days portraying another father-figure character. It’s worth noting that he still chooses to contribute his time to young filmmakers. Call it intuition (he does) but when it comes to finding the most interesting emerging talents to work with, Dafoe’s instincts have so far been strong. “What I liked about Olmo is that he does things simply,” he tells me. “I got to know him when he was a production assistant on At Eternity’s Gate [where Dafoe played Van Gogh] and when he finally asked me to be a part of his film, I said yes.” As an experienced actor, Dafoe was curious to support a young filmmaker going through the motions. “Sometimes, there’s a level of artistic corruption and fatigue that comes from success,” he admits. “Young people don’t have that. They have energy…a sense of hope.”

It can seem daunting, he admits, to navigate the relationship between an experienced actor and a first-time filmmaker. “There’s a slippery balance. I want to offer pointers. But I have to also remind them…I’m just an actor. I’m not going to carry this. I’m here to help you,” the actor explains. But there was another, more specific reason he decided to come on board: “Olmo speaks for people who are of another generation of New Yorkers, and that was attractive for me to understand.”

Dafoe has always kept one foot in an artier film scene, and this comes from his early days living in New York. Originally, the young Dafoe intended to become a commercial theatre actor in the city, but after serendipitously falling in with an artsy crowd in 1977, he took an interest in experimental productions and co-founded the dynamic Wooster Group troupe (it continues to this day). He was born in Wisconsin but he spent his most formative years in New York, having moved there for the first time when he was just 22, and he still visits frequently with his wife, the Italian filmmaker Giada Colagrande (the pair live together in Rome most of the time.) In conversation, he embodies New York in his way of speaking—that undistracted, familiar verbal rhythm that cuts to the point like glass, and makes use of subtle hand gestures and unsubtle shrugs—and when he reflects on his bohemian youth during the city’s 1970s heyday, a mix of roguish theatre troupes and punk clubs like CBGB or Mudd, his eyes light up.

But those halcyon days are behind him, he admits. Today, Dafoe is more likely to be tending to his small farm in Italy (where he raises alpacas) than being out on the town, and his interest in ashtanga vinyasa yoga is perhaps his hardest addiction of all—a form of yoga that is energetic and synchronises the breath with fluid movements. It is an essential part of his morning before he stands in front of the camera, and it helps him get into character: “Once I’ve done my morning routine, it’s like OK—I’ve done my work. Everything else is gravy,” he grins. It has a profound effect, he explains, not just on how he checks in on himself and his emotions, but also in the way he moves, and Dafoe is most certainly a physical actor, whose limberness has been used to add a freakish element to some of his stranger characters. “It makes me feel internally and physically strong, and that’s important because acting, to me, is about being a flexible instrument for the director to manipulate. But to get to that point, you must practise,” he says, giving me a serious look. “You do practise, right?”

Yes, I respond.

It’s not true. I don’t practise at all (there’s the odd Yoga with Adriene video on YouTube when the knees act up). But now it’s too late. I’ve just lied to Willem Dafoe. Not that he can’t see through the fib, as I sit there arched over the table with a posture like a misplaced ‘T’ Tetris block. But it was the manner in which he asked the question which caught me off-guard: almost like ashtanga yoga could be our mutual ground. For Dafoe, it’s obviously much more than a hobby, it is a way to live. “I don’t really want to get into it too much,” he adds finally with a grin. “Yoga is really misunderstood, and I never like talking about it.”