A Rabbit’s Foot sits down with the multi-hyphenate artist to discuss Poor Things, comedy, and the value in asking questions of the human condition.

He may be an actor, director, writer, and a stand-up comedian, but above all, Ramy Youssef is in the business of asking questions. “The art that I love asks beautiful questions about the human condition,” he tells me.

It’s true of his art too. The acclaimed TV show Ramy—which he writes, directs and stars in—sees him wrestling with questions of cultural and moral identity as a second generation American-Muslim living in New Jersey. His latest stand-up tour, Ramy Youssef: More Feelings, features new material that will soon be collected into a Netflix comedy special. It touches on similar conflicts through a more introspective, autobiographical lens, while the upcoming animated show co-created by Ramy has been described as following “The experiences of a Muslim-American family that must learn how to code switch as they navigate the early 2000s: a time of fear, war, and the rapid expansion of the boy-band industrial complex.”

Then, of course, there’s Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things, a gothic black comedy that, in Ramy’s words, asks the question, “what would happen if you followed your curiosity without any programming?” The film, which follows Bella Baxter (Emma Stone), a woman living in Victorian era London who embarks on a world tour of spiritual and sexual liberation, sees Ramy in his first feature role, starring opposite screen heavy-hitters Willem Dafoe, Mark Ruffalo and Stone—and he fits right in.

As he embarks on the next chapter of his career, Ramy seems aligned with himself, content with the energy he’s putting out in the world. “The prescription combo of prayer and therapy is pretty unbeatable,” he says, wearing a spirited grin. But as the conflict in Gaza rages on, Ramy is steadfast in his public support of a ceasefire, having announced only a few days before our conversation that 100% of the proceeds from his More Feelings tour will go towards providing humanitarian relief to the Palestinian people.

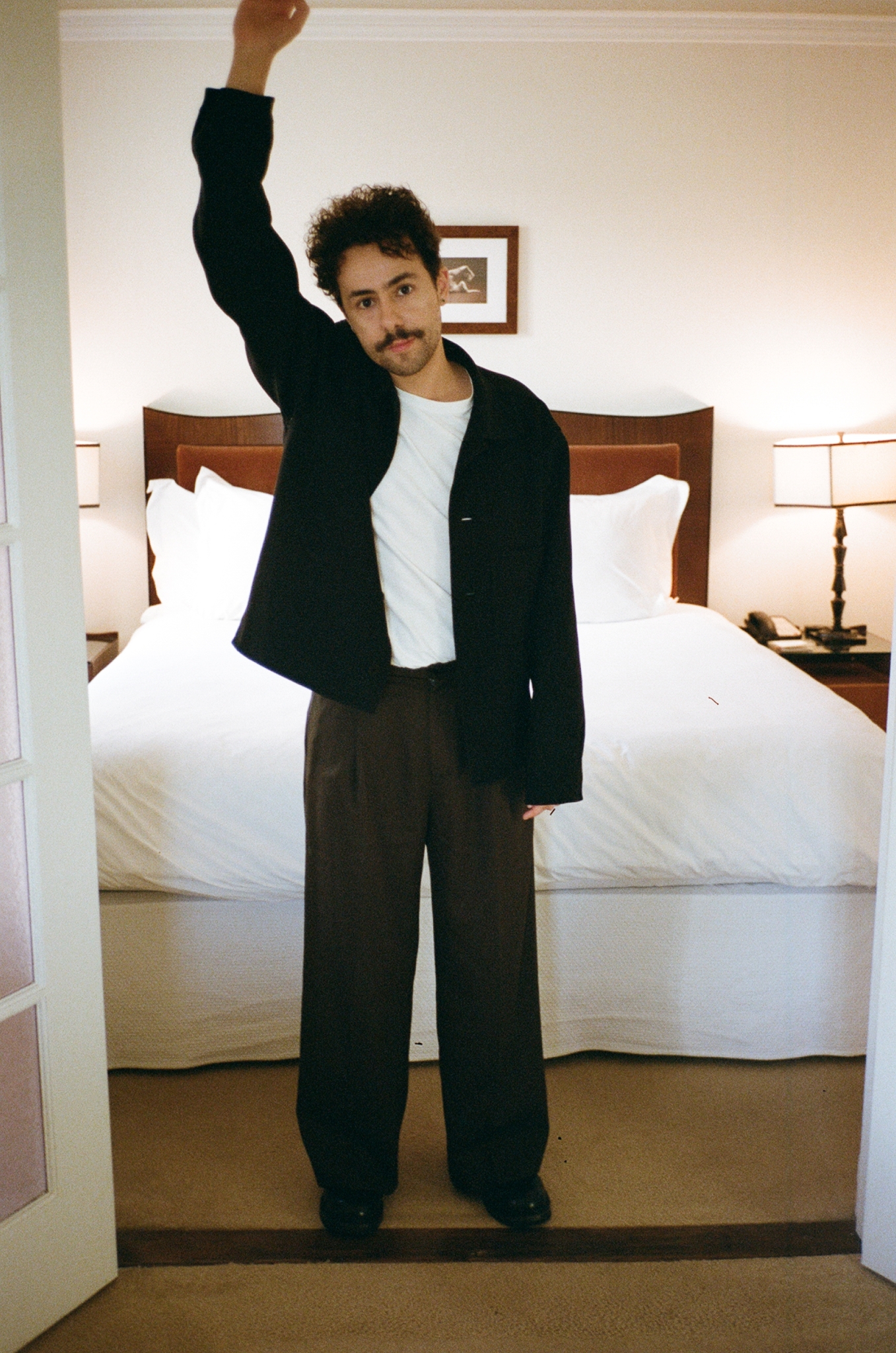

After our interview in London, our Creative Director Fatima Khan caught up with Ramy during this year’s Golden Globes and shot him at L.A.’s Chateau Marmont. Alongside these images, Ramy discusses Poor Things, how the new name of comedy is introspection, and why he’s protesting loudly in support of a ceasefire in Gaza.

LG: How did your collaboration with Yorgos come about?

RY: I work with a really great group of people. We made Ramy. We made Mo on Netflix. We have this new animated show. We always joke that we just kinda work like immigrants. From the writing, the acting, and the directing—we just do every part of it ourselves. To have Yorgos see the work, see the show, see the stand-up, and reach out to me to talk, felt like a gift that came out of nowhere. I’ve always approached my career without the expectation that anyone is going to do anything for me, or even know what to do with me. I would always have this thing in auditions where it would be like, “What are you?” They didn’t know what to do with me. I wasn’t quite the friend, and also not quite the leading man. In my mind, I feel like I am the leading man—so [with Ramy] I decided to write that into reality for myself. When you’re making art it’s like you’re putting out this bat signal to communicate with people who care about the same things that you care about. You’re not always making art for “fans”, you’re also making art for the artists that you want to be closer to, especially if you’re making something honest. Emma, Mark, Willem—these are people I’ve been watching my whole adult life, and now I get to play with them. Ramy Youssef & Mark Ruffalo on the set of Poor Things. 2022. By Ramy Youssef.

It’s not often a first-time film actor has their sparring partner be somebody like Willem. What did you learn from him?

I was impressed by his composure. The dude is a legend, and he’s going through three hours of prosthetics every day, and he shows up in the best mood. He’s playing a weird character but he’s still normal between scenes—normal for him—which is still really weird. It was great to be around people who are doing really in-depth character work, but it’s not that thing you think of when they’re in character the whole time. Willem doesn’t feel the need to push other people away in order to achieve greatness. He’s not trying to smoke anyone out. He wants to play. The whole cast had equal respect for everyone on the set regardless of role, and that was my favourite part of this whole process.

Where do you go after Yorgos Lanthimos? Do you want to keep working with prime-level auteurs or do you plan on directing your own feature? How do you want to approach a legacy going forward?

For me it’s about asking beautiful questions. The art that I love is about asking beautiful questions about the human condition. What’s exciting about Poor Things is that it’s asking the question: what would happen if you followed your curiosity without any programming? Without any of the social constructs that are put on to you by society, by your family, by your culture, and you can be uncaged in following that path. The work I like to write is thematically tied to a lot of spiritual questions. For me it’s about working with other artists whose work is centred around that in any form, and honestly, on any level as long as the question feels exciting and that there’s a vision around sincerely asking it.

LG: Is there a dream collaboration for you?

RY: Yorgos Lanthimos. When I first heard about the film, my reps told me it was just two scenes in the movie, and that alone blew my mind. I’m a really big fan of Alfonso Cuaron. Every time I’m about to write something I think about Children of Men—again, it’s a piece of art that’s asking great questions of the human condition.

How does that golden rule of starting a dialect cross over into your stand-up work?

My stand-up is all questions. It’s questions about guilt and shame. About spirituality. The best artists are seeing patterns and identifying them from their lens. But these are questions I’m mainly asking of myself. I tend not to make fun of anyone on stage unless it’s also about me making fun of me. Whenever I invoke someone else, it has to tie back to “What am I expecting of myself?” It has to come full circle—if it doesn’t, it feels fake to me, and it feels too easy.

That’s a trend I’ve started to notice with stand-up and art generally. Ramy, for example, is a way to start conversations that most wouldn’t feel comfortable having publicly. Jerrod Carmichael’s recent special felt like more than jokes, it felt like a heart-to-heart with the audience as if they were his closest friends. Dave Chapelle has done a similar thing in the past. It feels like you’re trying to approach your art in a similar way. Where has that shift in stand-up come from for you?

We’re inundated by choice. If you look at the internet, at TikTok, at Instagram, even memes. I love memes. They’re really funny. My quickest, largest laugh is coming from a meme. With that in mind, if I’m inviting you to sit with me on stage for an hour, I want to give you a big laugh, but I also want to make sure it’s part of digesting something you could only get from an hour-long commitment. I don’t want to give you an hour of me trying to be as funny as memes, because I’ll probably fall short after 15 minutes. So, while I have your attention, how can we get a bit more intimate? It’s important that it also stays funny. I don’t want it to be therapy—I already go to therapy, I can do all of that there. The prescription combo of prayer and therapy is pretty unbeatable already. But I do like to lock up the phones. I want my audience to show up and be there. How often are you not asleep and not looking at your phone for longer than 90 minutes? That’s what intimacy is now. I cherish those spaces, and I feel lucky whenever I put on a show and people come out.

LG: A lot of your material is about your family life, your culture, your upbringing—is there a difference between a British crowd and an American one?

RY: I love performing in London because of how it actually feels like there’s no gap in the understanding. The thing I always love exploring in comedy is the push and pull of the highest self and the lower self. It’s why everyone who comes to my show is like “Wait, this crowd is pretty fifty-fifty. It’s like hipsters and hijabis.” There’s going to be headscarves and there’s going to be at least 40 guys wearing thick, black-rimmed glasses. There will be two fedoras, minimum. But I think anyone who’s into fucked up introspection is going to have a good time. When I’m exploring stuff, I’m examining myself, so the byproduct of that is a lot of it will fit in the cultural bucket. But that’s not what it’s about, even if it is what it’s about. That to me is why it works almost everywhere I go. If a joke I do only works in New York, I tend to drop the joke. I’m about to do Paris, Copenhagen and Berlin, and I’m excited. I’m ramping up to do my special, and I want it to feel global.

Have you put a shelf life on Ramy?

We’re figuring it out. I’ve always had a vision for the show that it never really ends, but we’ll have the grace to make seasons when we can. These are characters that you’re excited to see grow—and time only helps.

You’ve been very vocal about a ceasefire, and you hosted a fundraiser in New York a few nights ago with the proceeds going towards Gaza. Did you ever feel any pressure from the industry, or from yourself, to not speak about your position in this conflict? Why has it been important for you to take a stance publicly and loudly?

It’s important to unplug from how divisive the internet can feel. On one hand it’s incredibly educational, and a lot of people are getting informed in a really meaningful way, and I also think a lot gets lost in tone. A lot of our humanity gets lost when we can’t look at each other face to face. I’ve never felt like I can’t express what I feel when I’m face to face with anyone in my

industry or my friendship group. There’s a way to have these conversations and still share humanity and still walk away friends. That’s been my experience. That’s where I want to meet people. A lot of the efforts we’ve put together on a project like Artists4Ceasefire is with the reflection that no one looks back on history and tends to be proud of a bombing campaign that involves human beings, and civilians. I’m not a history teacher, I’m just really an advocate for human introspection and connection, so I see what’s happening to vulnerable people including children and I feel compelled to speak about it. But I always have. It’s always been a part of the work, way before it became a large global headline. For anyone who’s outside of Hollywood, I wouldn’t buy into the noise, Hollywood is incredibly open minded, and people are incredibly beautiful. Maybe people are hurt and they can say certain things in certain ways, but I feel like we have an opportunity to broadcast something incredibly loving out to the world, and we should be taking it.

In Ramy, the conflict is hanging over his head for essentially the whole of season three. You handle it in a way that is funny and harrowing and nuanced, which is the beauty of the show and always has been. Does comedy have a place during these deeply traumatic times? Is there a boundary for comedy, a line that shouldn’t be crossed?

It’s all about what you feel the goal of comedy is. I’ve wrestled with the effectiveness of comedy myself, and I’ve found that it’s not as change-making as a lot of people try and bill it. What I’ve felt from people coming out to my shows over the last few months is that the collective laugh acts as a recharge of the spiritual battery. If you come out to my show, you may not find the solutions you’re looking for, but if it gives you a break from crying and feeling depressed, so you can laugh for a bit, then that makes it feel worth it. But there’s a very fine-line between doing that and trivialising what’s happening. That’s a tightrope that I walk.

Do you enjoy walking that tightrope?

It feels worth it because it’s not easy.