What’s your beauty routine? Vogue tells us Margot Robbie’s is ‘psychotically perfect,’ while Christy Turlington once said it was the question she found the most stupid. One thing is certain: it is now ubiquitous. All over social media, tweens and twenty-somethings are busy filming themselves “waking up” in the morning, walking through their concealer and callisthenics routine before slipping into a tightly choreographed outfit. Some seek to sell a lifestyle (get ready with me, say, for a 5am jog); others simply wish to show off a fabulous wardrobe (‘This is the full ensemble, darlings,’ coos drag queen Jeauni Cassanova). Others still anthologise their #recentfits, keen to document how often they’ve worn the same pair of jeans in one week in a bid to prove they are #sustainable.

You may see this craze as the logical next step after the #ootd trend of Instagram’s earlier years – a new way to package sartorial flair. But the source arguably lies beyond social media and sits in the canonical beauty routines of Hollywood films of the 2000s.

What defines today’s beauty reels, to me, is not narcissism. Rather it is a weird sort of tension between detachment and intimacy. Influencers turn their toilette – a private ceremony – into a public audience. By putting such an act out there for all to gawp at, they turn their ablutions into a collective ritual.

That paradigm shift began in earnest in the year 2000, when Patrick Bateman peeled off his facemask and uttered the words known to all American Psycho fans: ‘There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman – some kind of abstraction. But there is no real me. Only an entity.’ Here is someone who does not think having a beauty routine is stupid, and who enumerates the various lotions and moisturisers he uses in a Dorian Gray-like attempt to preserve his youth. It is ironic that he does not mention concealer, given he will spend most of the film trying to hide his crimes. For the uninitiated, you can watch his full routine on YouTube (my algorithm lists Margot Robbie’s ‘psychotically perfect’ routine as up next).

Patrick Bateman uses intimacy as a ploy, conning girlfriends into a position where they feel comfortable and then viciously murdering them. The whole thing is a metaphor for corporate greed, so it’s really no surprise that his techniques resemble those of the online influencer. Both exist purely for gain, every action or item worn a vehicle for enrichment. They thrive on others’ insecurities and a society/algorithm that eggs them on. Even more specific touches, like Bateman’s lotions, find echoes in the beauty reel. Where men were once expected to shave and get dressed, today their ablutions are more complex and particular: exfoliants, body balms and even nostril trimmers are now commonplace. Dressed to kill? Try groomed to kill. (The poster for American Psycho hints at the darkness beneath Bateman’s ‘killer looks’, with that very phrase written beside a chiselled Christian Bale who pouts and brandishes a shiny knife).

What defines today’s beauty reels, to me, is not narcissism. Rather it is a weird sort of tension between detachment and intimacy. Influencers turn their toilette – a private ceremony – into a public audience. By putting such an act out there for all to gawp at, they turn their ablutions into a collective ritual.

Bateman operates in a world that is obsessed with appearances: the police ignore his murder confession because he presents as a smart, upstanding citizen. To survive in this world – and ours – is to subscribe to an imitation game. The modern face of the beauty routine is, like Bateman, in the business of copying those who already look good, and often at the cost of their own identity. It also goes without saying that the influencer’s days are numbered: but as we face an evermore powerful anti-ageing cult, many end up in denial. Even the youngest influencers are in the business of imitating youth rather than enjoying it: they are energetic and peppy but the whole thing is a performance. Bateman himself was only 27.

The beauty reel is a simulation of intimacy that hinges on self-effacement. As Bateman himself says: ‘I simply am not there.’ Miss Congeniality, released the same year as American Psycho, teases out a similar tension. The protagonist is Gracie Hart (Sandra Bullock), an FBI agent and professional tomboy who must pretend to be a bimbo in a beauty pageant to stop an evil plot. She has never felt less like herself than when she catwalks out of the warehouse where her transformation took place (I mean that literally: she falls in kitten heels). Her beautician is a Victor Melling, played by Michael Caine, who orchestrates the greatest makeover scene in cinematic history. ‘Attention,’ a woman’s voice echoes across the warehouse. ‘All hair removal units – wax, electrolysis – to commence at 2300 hours.’ Melling, in a camp pink shirt, instructs stylists to make Hart’s hair ‘more fluffy’ and stands in hilarious contrast to a dark, military backdrop. Yet it is he who ultimately pulls the strings, and persuades a fashion-averse Agent Hart of how vital his job is. By earning her respect, he gets her to take the operation seriously.

Caine’s character is essentially the same as social media’s: he is omniscient and everywhere, scrutinising Bullock and noticing (when no one else does) that she is hiding cupcakes in her dress (carbs, for Christ’s sake!). He is also a dictator of taste, an etiquette nazi, and a man who sets nigh impossible standards for women to imitate. Pageantry is in every way the opposite of privacy: Hart not only surrenders her name but also her right to intimacy (hard as it is for an FBI agent to have any to begin with). Even though she ends up enjoying aspects of life as Gracie Lou, and learns a great deal from it, she does so at the cost of discretion.

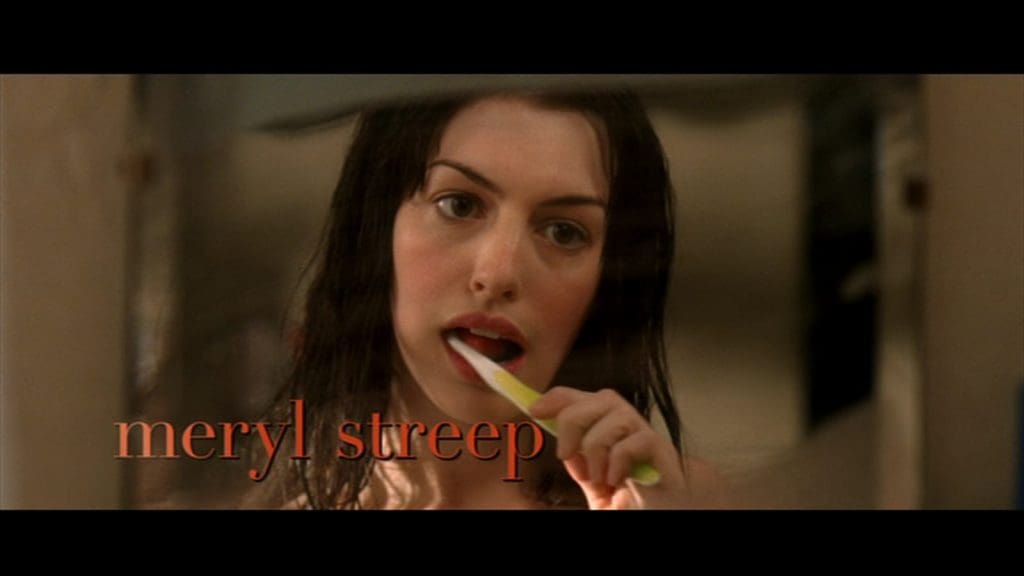

The tension between intimacy and detachment is also one between focus and absent-mindedness. In the opening scene of The Devil Wears Prada (2006), Andy Sachs (played by a young Anne Hathaway) brushes her teeth, hair, and throws on some lipstick all on autopilot, as she focuses on memorising cue cards ahead of her job interview. The footage is interspersed with parallel morning routines – those of the pedigreed female employees of Runway, a fashion magazine where Sachs will end up working. The juxtaposition of socks and stockings, Gap and Guerlain, is not just a tale of two outfits but of personal differences: between those who think looks are secondary to success, and those who equate the two

When Sachs struts into the Elias Clarke building, she frowns quizzically at a high-heeled employee – one of the very women whose meticulous beauty routine is shown alongside hers. Sachs is swiftly schooled by the redoubtable Miranda Priestley, who tells her the ‘lumpy blue sweater’ she has elected to wear tells the world she ‘takes herself too seriously to care about what’s on her back’, and that her anti-materialistic pretentions are foolish and out of touch. Priestley is the high priestess of icy aloofness, a woman who uses detachment as a coping mechanism to get ahead in a world dominated by men. As the editrix of a fashion magazine, to say beauty deserves to be beheld is to underplay the very reason for her professional existence. On her watch, beauty and fashion thrive as a cult that relies on an adoring but inferior public: the relationship between them and her is both intimate (they worship her magazine) and detached (she does not give them the time of day).

But what is real intimacy anyway? To go to the root of the matter – etymologically speaking at least – it is about contact (from the Latin intimare, to impress). ‘Why is it that putting a tie onto a man is even sexier than taking it off?’ asks Carrie Bradshaw in Sex and The City as she gazes into the eyes of her noncommittal boyfriend. The most intimate act of all is not to take off our clothes, but rather to put them on in the company of strangers. It is not during sex or foreplay that we typically show our true colours, but rather the morning after as we re-enter the world as a pair, pulling on the T-shirt we so keenly ripped off the night before. It is then, with the grim possibility of gunk in our eyes, that we are at our most naked.

his type of – real – intimacy is at odds with the format of the social media reel. Even on joint TikTok accounts shared by couples, it is impossible to fully suspend our disbelief that what we are seeing is authentic. That kind of contact can never be sincerely simulated by someone who knows the camera is there.

Modern filmmakers know this and since the advent of social media have tried out different ways to produce raw and real intimacy on camera. Often, that means away from the watchful eyes of other characters, and making the moment deliberately unspectacular. The first time Elio and Oliver have sex in Call Me By Your Name (2017), the camera literally pans and we do not even get to see it. The last glimpse we are offered shows them both still clothed. (Could the Sicilian director Luca Guadagnino have thought of etymology as well? Intimare gave way to intimus – the closest to the inside – and the tunica intima – the undershirt. The Italian intimità is not far behind…)

Recently, things have gotten more meta. In Barbie, the very possibility of intimacy is thwarted by the characters’ mechanical limitations. ‘I thought I might stay over tonight,’ a desperate Ken tells Barbie, who then asks, ‘To do what?’ After a pause, Ken replies he’s not sure. Greta Gerwig’s film also has something to say about beauty routines, making Barbie’s caricatural to a fault. At the outset she exists in a kind of metaverse: a dream-like space concocted by the girl who plays with her. In many ways it resembles the worlds of Instagram and TikTok: manicured, voyeuristic, woefully saturated. Barbie performs her ablutions for all to see: she’s still in bed when another doll waves at her saying ‘Hey Barbie!’ There is no privacy: everyone is an exhibitionist. The whole thing feels perverted, like beauty reels themselves.

If a beauty reel is doomed to only ever achieve partial or fake intimacy, it still finds its roots in cinema. Rewatching Christian Bale perform stomach crunches with an ice pack around his head is to realise Patrick Bateman looks alarmingly like the svelte, self-adulating boys-to-men of today, who ritualise their first waking hour in handsome minimalist flats for social media validation like urbane little Andrew Tates. They know that intimacy, when contrived and artificial, sells. Even the faded light and muted colours of the beauty reel are lifted straight from the American Gardens Building: a sleek, functional aesthetic that exudes wealth, anxiety and disinterest.