For thirty years, Benoît Delhomme has been most commonly known as a cinematographer, and you’ll recognise his wonderful imagery in films like The Scent of Green Papaya and What Time Is It There?, The Theory of Everything and many others. Though, over the years he’s proven himself as proficient with a brush as a camera, and his paintings illustrate a poignant crossroads with life, art and movie-making. He’s also begun to stretch his cinematic horizons further than ever, having just wrapped his directorial debut Mother’s Instinct, starring Jessica Chastain and Anne Hathaway. Below, Benoît goes deep on his experience working with the likes of Tran Anh Hung, Tsai Ming Liang, and Al Pacino. He also waxes lyrical on Matisse, the beauty of slow cinema, his love for painting, and the trauma of filmmaking.

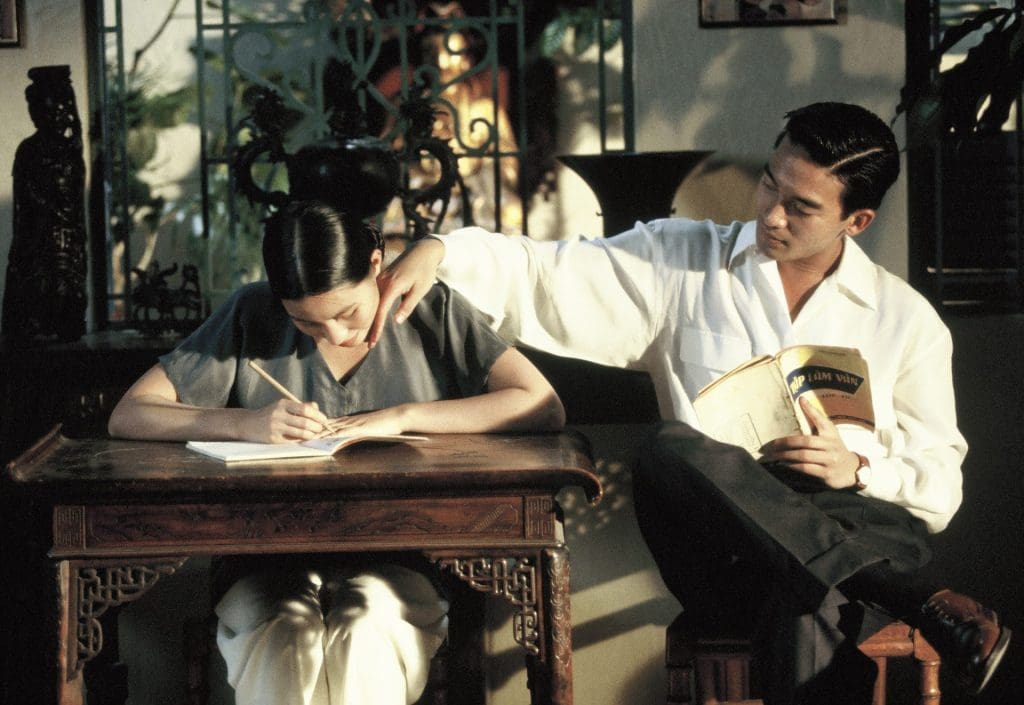

On The Scent of Green Papaya

I knew it was about 30 years since the movie—I couldn’t believe it. I was lucky to start my career on a film like this one. When you’re a French cinematographer you think you’re going to spend your life making French comedies, shooting a lot of diluted dialogue. In France, 30 years ago, the visual ambition in film was small. Directors were putting all their energy in the actors and very simple stories. And they didn’t want the stories to be distracted by the visuals being too strong. Tran Anh Hung has such a poetic vision of film. He wanted the film to be poetry. Poetry of the image. Finding the right transparency of the leaves. Trying to find the right texture. Professionally, ‘poetry’ was a new word to me.

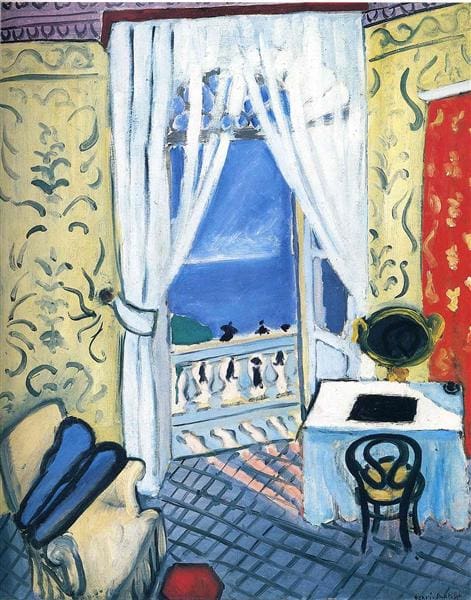

On Matisse

Before filming The Scent of Green Papaya, Tran Anh Hung showed me a painting by Henri Matisse. It was something called Interior With A Violin. He said, I know it’s not realistic, but this is exactly the kind of light and colour I would like in the movie. At the time, people were so obsessed with realism. But he thought it was more interesting to take inspiration from Matisse rather than other movies. I never saw myself as someone who wanted to make reality, in anything, I like to improvise with my feelings. I want to dig in different territories, I don’t want to be stuck with reality.

On Cyclo

For The Scent of Green Papaya we went to Vietnam for a few weeks. I saw the country, it was a big shock to my senses, and then I had to go back and literally adapt my memory of the country on a soundstage in Paris. But for Cyclo, we knew we wanted to shoot in Ho Chi Minh city, we knew we had to do it for real this time. It was incredible. I spent six months there. We were shooting for real in the city, we built sets in the middle of the main square in Saigon. We had thousands and thousands of extras passing through all day long. I can’t believe Tran had the energy to do all of that, to shoot there for real. On Cyclo, he had a very different attitude to the aesthetic he wanted. I was a guy coming out of film school trying to respect the rules, and The Scent of Green Papaya is full of rules. It’s a “perfect” movie. Cyclo was all about breaking the rules. He said to me ‘for this film, I would like you to imagine that every scene can be its own world—be open to new colours, new contrasts, new textures. I don’t want this film to look like just one thing.’ Many movies look the same from the first to the last shot. For those movies it’s all about consistency. For us, we were in the bubble of Vietnam. So let’s embrace the violence of the colours of this country. After thirty years in this field, It’s still the most powerful shoot of my life. I discovered so much. I found new ways of lighting at the time, using fluorescent tubes. I opened myself up.

On Slow Cinema

I’m not doing films to tell complicated plots. I don’t believe in lots of twists, and speeds and action. I can certainly do it, but my brain is more drawn to slow cinema. I love paintings too, so In cinema, I love when an image can take the time to tell you what’s happening within the frame. I consider Tsai Ming Liang a monk of cinema. When I worked with him, [on What Time is It There?] I learned a lot. He has an incredible sense of time passing. Transcendence. It was a beautiful shock. Even the slowness of the process was invigorating. We would take four hours to set up a single frame. We would sometimes do two shots a day, maximum. Everything was very slow and meticulous and beautiful. People nowadays don’t have the time to spend watching things, but It’s like a painting—there’s beauty in the audience sitting there and absorbing a single frame .With Tran Anh Hung or Tsai Ming Liang you can shoot a cup of coffee and make it meaningful. You can give soul to anything. A piece of fabric hanging on a line. You don’t need dialogue. The visual language of film is universal. The more I live, the more I want simplicity in the work I engage with.

On Tsai Ming Liang

Tsai Ming Liang took extreme simplicity to such extremes. For many years, he would use the same apartment as a set, he would re-decorate it for every film. It was a stage for him in a way. When we would arrive at the flat to shoot in the morning, he had on the page just a few ideograms of what scenes we would shoot for the day. Of course I couldn’t read in his language. He would talk to his team in his language, and so all I could interpret was the sound of his voice. And the sound of his voice describing the day to the crew would put me in some sort of meditative state. Afterwards, when the crew would translate what he said to me in French, I would still prefer the voice of Tsai Ming Liang. I understood more about his intentions without the translation. Just how you can’t verbalise the music of the world. The language of film doesn’t need to be the same language. I’ve worked with many directors from many different countries, and that’s only possible because looking through a camera together is a language unto itself. With Tsai Ming Liang it was like that. It was an interesting cultural exchange, we brought each other a lot.

On Mother’s Instinct

I was supposed to be the cinematographer on this movie. Because I’ve known Jessica Chastain and Anne Hathaway for many years, I’ve worked with them both. I worked with Jessica on her first movie, Salomè, directed by Al Pacino. One week before the shoot started, the director, Olivier Masset-Depasse dropped out, and Jessica asked me to step in. I had a few hours to make up my mind. It wasn’t something I had planned. I always thought that my first film as a director would be much like my paintings. Very small budget, very free, with a personal subject. My own script. Unknown actors. My own universe, and my own memories. Suddenly, I’m working on this movie with no prep, a script I didn’t write, with two huge Hollywood actors. It was a huge challenge. But I said yes. The film is an english-language remake of the Belgian film of the same name, by the same director [Masset-Depasse]. It’s a thriller set in the 60s about two neighbours living in the Suburbs of New Jersey, and they both have a son. It’s a portrait of these two women, who are very good friends to start but whose relationship becomes more tense as the film progresses. It’s very Hitchcockian. Jessica says it reminds her of What Happened To Baby Jane?. That’s quite right. I tried to make it very simple, visually, and to put all my energy into working with these two actresses. That was new to me. As a cinematographer, I never talk to the actors. I want them to feel me there, and feel that I’m there to protect them and capture them as well as I can. But I want to be invisible. Actors like that from me. But here as a director, my place was different. That was the biggest learning curve, to learn how to approach the actors from a director’s point of view.

On Al Pacino’s directing style

I met Al while working on The Merchant of Venice, a Shakespeare adaptation. It was a few years before Salomè, and I felt a great, unspoken connection with Al. We felt each other—he would look at me, make a small sign or facial expression to communicate with me, but we never talked during the shoot. But I could feel he liked me, from day one. When he decided to adapt Oscar Wilde’s play Salomè, he called me and asked me to help him make this very tiny movie in LA. He was already doing the play of Salomè. He was doing the play at night, and during the day he wanted to shoot the film version. He had a very clear vision. He wanted it to be a Salvador Dali collage. Early Bunuel. He wanted something of that intensity, and he would star and direct. One day we came on set and Al said to me “Benoit, for this scene, try not to shoot me, I don’t feel right, I don’t feel in a good mood. Shoot all the actors, improvise, but don’t let the camera stop on me.” We started shooting, and after a few minutes I realised that despite his words, Al is, of course, performing incredibly. He was so good that I felt like I had to stop on him. So I’m panning the camera to the other actors, but also trying to capture him, and feeling very insecure about what I was doing. Suddenly, Al screams “CUT”. He looks at me and says “Benoît, come with me, we need to talk.” Jessica looked at me with a terrified look. I’m terrified. We go into the other room and he says to me “Benoît, look at me, who is the star of this movie?” and I shyly reply “you are, Al, of course”, and he said “and so why are you not shooting me?” [laughs] he said “you are here to capture my soul”. Imagine Al Pacino saying that to you. That line has stayed with me forever. I’ve since made many paintings about this phrase. It was only later he told me he only said that to create some drama for the scene [laughs]. I think about that moment all the time. I realised that it wasn’t against me when he said that. What I realised working with Al so closely is that there is not one director who he feels has completely captured who he is. No director can be good enough for Al Pacino. It’s not at all an insult to any of those other filmmakers. He is just that good. He still hunts for the perfect director to unlock his full potential. It was beautiful to be filming him, to try and be one of the best, to film him like no one had done so before.

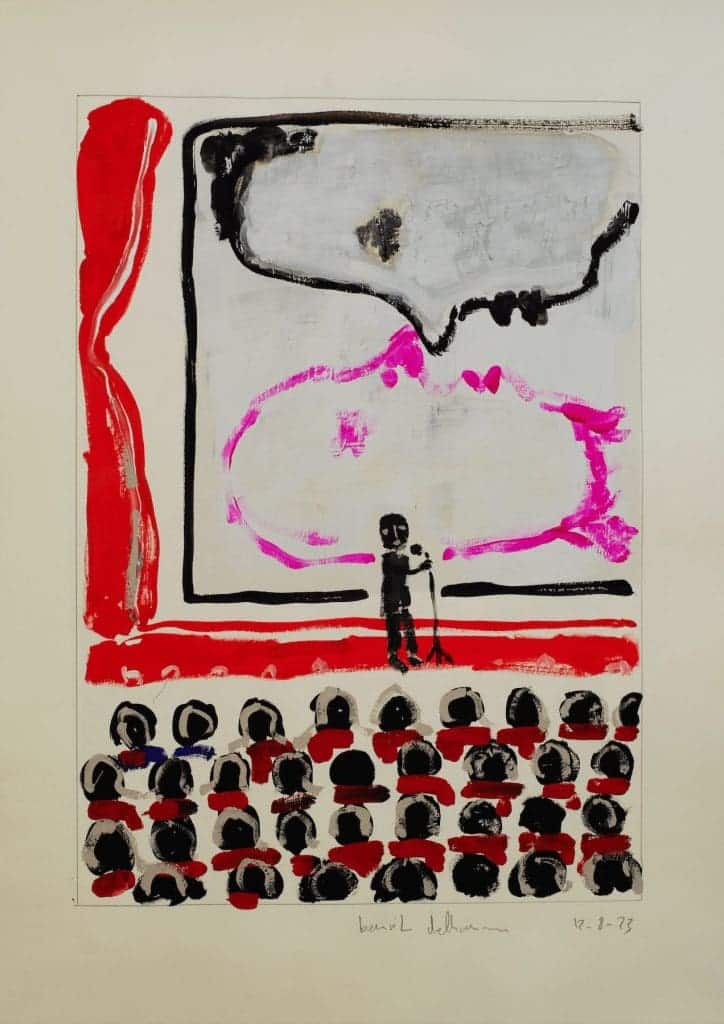

On Painting in Secrecy

The paintings I make are very intimate. As a cinematographer, you don’t talk about yourself. You only talk about yourself through the images you make for someone else. You have to be a psychoanalyst of the director, you work on his memory of things, of his ideas and sensitivity. You’re supposed to bring him images he can only describe to you. A lot of cinematographers do this very well, and I did too for a time. But I realised I had something to say for myself, and I felt painting to be the best way to do this, because I could do it on my own. I could imagine and build these worlds based on my own memories. It helps me say things that I can’t say with cinema or in words, as I’m certainly a shy person. It helps me communicate with people. At the time I thought it was risky to show to people, as I was showing a side of myself I had never shown before. In cinema we are criticised so much, now you make an image, and people start telling you they don’t like what they see in the top right corner. With painting, I wanted some space in my life and nobody could destroy it. It was a way to experience complete creative freedom.

On Finding a Balance of Painting and Cinema

I have two worlds in my paintings: one has no relationship to cinema—very primitive, completely from my imagination—and then another world is very connected to cinema. I asked myself, after many years of painting, why I should disconnect the two artforms. So sometimes I use things I’ve heard on film sets, and sometimes I’m channelling a certain trauma—of my 40 years of experience in the film industry. When you read things about the act of making movies, it seems like a film shoot is a love story. It’s not like this. It’s not a peaceful journey. There’s a lot of anxiety and conflict. Often filmmaking is disharmonious, because everyone is trying to create something beautiful in front of everybody else. I paint with the damage that cinema inflicted on me. When I sit on a stool to make a painting, I see myself on a film set, and I think about the process, and sometimes I miss my crew—I miss talking to people, experiencing their energy. Painting is sometimes very lonely. But also, when I make a film, sometimes I just want to abandon the set, get in my car and go home to my painting studio. For the last 20 years, I have tried to balance the two, because I need both. Both worlds give me so much.

You can find the print version of this issue by visiting our shop page!