In 1971, in the darkened cabin of a 747, I saw my first adult film, and by that I mean, a film for grown ups. Thirteen years old and obsessed with all things cinema, up to that moment, mid-way on the long flight from London to Los Angeles, the films I had seen could not be described as high brow or art house fare. The cinema I appreciated had spectacle, escape, lots of plot, epic battles between heroes and villains, and the odd – and to my thinking – unnecessary bit of kissing.

(I can confess now that I saw the western Bandelero four times in one week at a cinema in Leicester Square and teared up every time Dean Martin died in his brother James Stewart’s arms, and had an unaware prepubescent crush on Raquel Welch.)

Luckily, my parents were liberal minded and allowed my two younger brothers and I to see whatever was playing and had a rating we could blab our way into, this expanded when my father got a 16mm projector and an account at the Rank Film library. My brothers and I created our own film society, and our education now included the likes of The Wild Bunch, Soldier Blue, Night Of The Living Dead.

Nothing prepared me for the film I saw on that TWA flight. (N.B. In those days, a screen was pulled down at the front of the cabin and literally projected, suddenly becoming a cinema at 30,000 feet above ground. Usually there was one feature and that was your lot. Something safe for the whole family). Recently airlines like TWA and PAN AM, in an effort to be seen as having a bit of class, started showing a second feature, of a more sophisticated fare. When the stewardesses had not raised the white screen at the end of our feature film and instead announced there would be a second feature. A second film! I thought: “How lucky was I?”

Five minutes after the second film had started and the actors were speaking a language I could not understand, with writing on the lower part off the screen telling us what they were saying. I thought maybe I’m not so lucky, but as the old joke goes, at 30,000 feet you can’t exactly walk out. So, I settled in and gave it a go. And that is how I came to be watching the French art house sensation Claire’s Knee (Le genou de Claire) by Eric Rohmer. (Rohmer, like a couple of other prominent French directors of his time, started as a film critic for Cahiers du Cinema.)

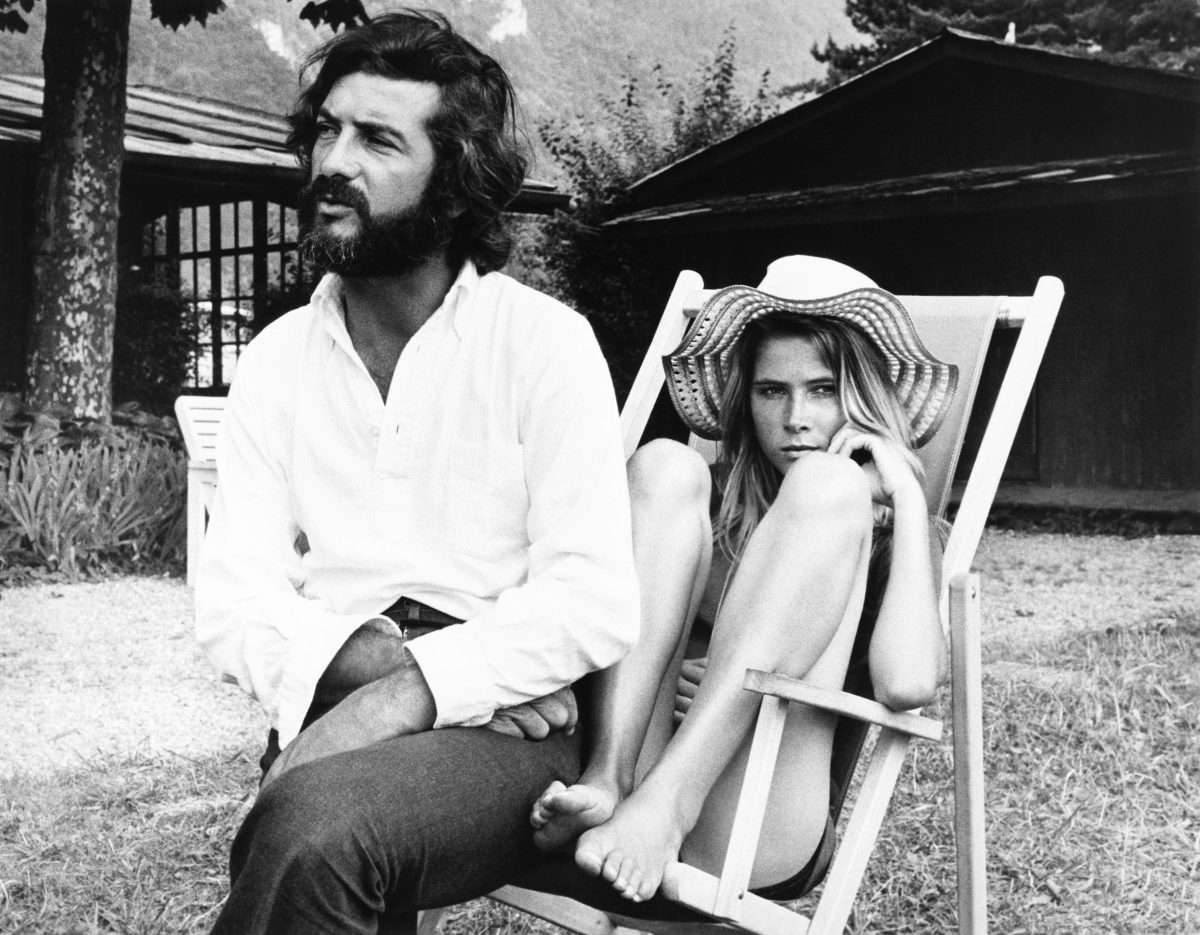

For those of you who haven’t seen Claire’s Knee, the setting is one of those idyllic French summers on a lake, where everyone seems to be on permanent holiday staying in large rambling houses by the water. Our main man, Jerome, with a mop of black hair and burly beard, motors around the lake in his flashy looking sports boat. He is about to get married and has come to sell his large house. He runs into an old flame, the alluring Aurora, a novelist, and they talk about lots of things (there is a lot of talking in this film), specifically though, they discuss how such a ladies man as Jerome could be settling down. And the gist of the film is that. Temptation comes Jerome’s way, and as in many French films, temptation comes in the shape of two young nubile girls, and not the more age appropriate women who are also holidaying by the lake.

I think it’s important to add here that Jerome is actively encouraged by his old flame Aurora, who sees these temptations as the possible fodder for the new novel she is writing. So Jerome talks and flirts with young nubile Laura who has a crush on him, they sit by the lake, go on mountain hikes, discussing their phantom relationship and why it can never be until Jerome out of the blue kisses her full on the lips, and Laura pulls away. Later, Jerome repeats every detail to Aurora, who listens without judgement. And then it’s all forgotten because Laura’s step sister – the older but still nubile Claire – shows up to stay. One afternoon helping her boyfriend pick cherries from a tree, Claire stands on a ladder in her short skirt and Jerome catches sight of her knee, and that is the rest of the film, his struggle with his desire for that knee. All very French.

When the film finished and the cabin lights came up, I wasn’t sure what I had watched, except it was like nothing I had ever seen. Truthfully, most of the film had gone way over my head, and boy did those characters ever talk and talk and talk. But…

It is the time now for films from twenty, thirty, even forty years ago, to be brought up before the court. Films once celebrated are now languishing in movie jail. When Charles (as in Finch) asked recently how Claire’s Knee would have been received today, I told him how I had come to see the film and he asked if I would rewatch it and then write about how I found it now. So, after having not done so since that TWA flight, I did.

The film is beautiful, it was photographed by Nestor Almendros who would go on to shoot Days Of Heaven, assisted by Phillipe Rousellot, he of Diva and Dangerous Liaisons. The location is so stunning it makes you want to tear up your passport and emigrate immediately.

Jerome is played by Jean-Claude Brialy (the go to actor of his day for all the french directors of the famous Nouvelle Vague) and he uses that speed boat to go between the women on the lake with a slightly predatorily air, rather like Warren Beatty pursuing the women of Beverly Hills on his motorbike in Shampoo.

Jerome and Aurora have what can be described as a “handsy” relationship. They are either stroking one another, fondling each other’s hair, toying with each other’s clothes or slowly enveloping an arm over the other’s shoulder like a snake around a tree limb, as they talk and conspire and confess. Their relationship brought to mind Valmont and Merteuil in Les liaisons dangereuses (or Dangerous Liaisons that Rousellot was to film many years later), where tasks of seduction are set in a competition to see who has the least morals. Aurora’s test for Jerome is different as neither of them want him to succumb to the temptation itself, but rather it will be his struggle that interests Aurora and which Jerome is willing to engage with for the artistic endeavour of her novel. It’s all for art’s sake.

Laura, the first of the young nubile girls, is very, very young. Of course, when I first saw the film, she was at least a couple of years older than me and brought to mind a cousin I had who, when we used to go on holiday, would always seduce men ten years older than her. But now? Whoah. As Jerome and Laura’s relationship progressed, I again thought of another film, Woody Allen and Marie Hemingway in Manhattan – no longer a favourable or comfortable comparison these days. To be fair, Laura’s crush on Jerome is an open topic between them and he repeatedly tells her why she cannot compete with his fiancee, but like his relationship with Aurora, it is very tactile – nay “handsy.” That he is the same with Aurora either explains this behaviour as personal to Jerome with all women, or Rohmer directed him to behave that way so that the audience would accept it as that. The kiss on the lips maybe not so much.

Another side note: I have just made a film where the main character a male high school teacher in his fifties, sees one of his students, a seventeen year old boy, hungrily trying to force something out of the snack machine. He offers him a candy bar he has brought to class for himself. A comment I got back from one of the viewers of my director’s cut was that the teacher was obviously a paedophile and they were waiting for him to pounce, but he didn’t because he isn’t. At some point we have to look at what is actually happening instead of how much is projection.

The introduction of Claire and her knee takes the film away from what is interesting about the relationship between Jerome and Laura, and into the mind of Jerome. He again confesses to Aurora that what he desires utmost is to place his hand on Claire’s knee, admitting that is the extent of his attraction as he knows her hardly at all. He gets his chance, sheltering from the rain with Claire (after a boat ride!), she is weeping after he has told her that her boyfriend has betrayed her, as he consoles her he places his hand on her knee, slowly stroking it. Not the leg. Or thigh: ust the knee. Claire looks at him confused, expecting maybe he might pounce, but he doesn’t, and she goes back to crying until the rain stops,

The film ends soon after. Jerome leaves for good, his obsession with Claire’s knee dispelled, all the characters disperse and Claire makes it up with her boyfriend. Watching the film again, once past the nostalgia, I was impressed. Rohmer told his tale through talk, with characters who revealed themselves while the other character listened and then answered and that was the action, the plot. My favourite film this year is The Worst Person In The World, where characters talk and listen.

I told neither my mother or father about that second film on my solo flight from London to Los Angeles, but the next time my brothers and I put in our order at Rank Films Library for our weekend viewing, my choice was My Night At Maud’s. Not a popular one in our film society. Rohmer led me to Truffaut, which led to Malle, then [Claude] Chabrol, [Jean-Luc] Godard, and [Claude] Lelouch and finally to the grandmaster, Renoir. I actually became a bit of a French film snob. It was when my mother took me to see Day For Night (La Nuit Americaine) that I realised I wanted more than to watch films, I wanted to make them. And I have Claire and her knee to thank for that.