When the Royal Ballet Principle dancer Marcelino Sambé, bursts into the library at the Nomad Hotel, he greets me enthusiastically: “It’s so great to see you during the day!” This is in reference to the fact that we had previously met at several parties around London, where he possessed an effervescent charisma that is still a constant during our lunchtime interview.

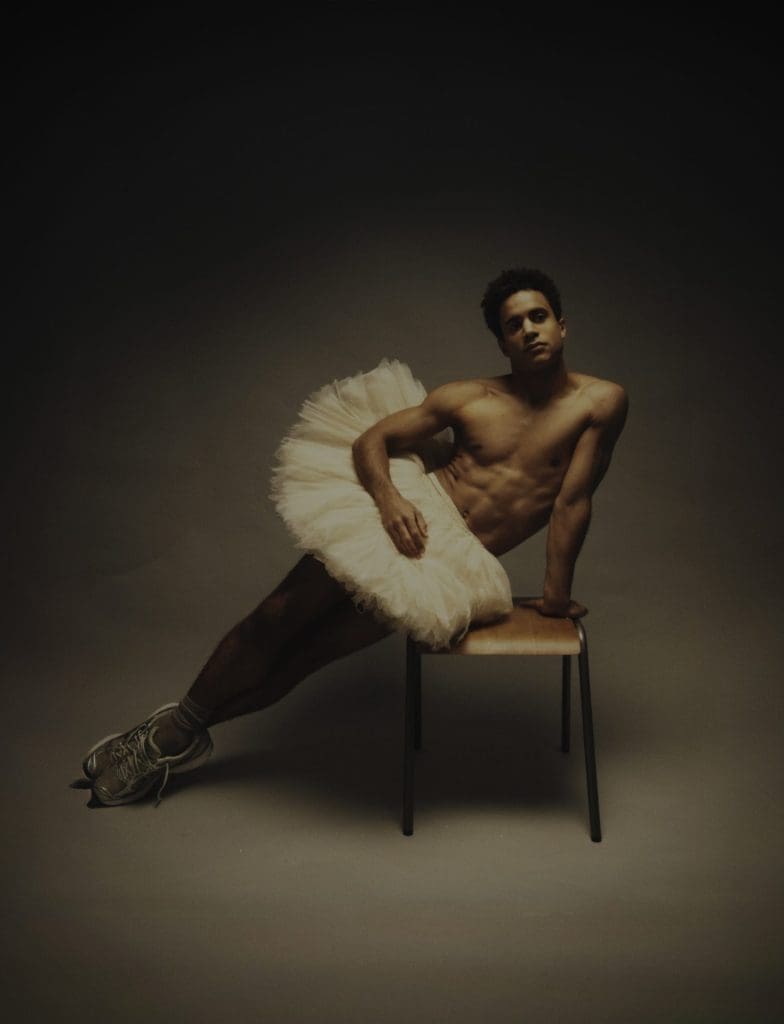

Sambé wants to change the perception of what a ballet dancer can be. Taking a break from ballet at the beginning of last year due to an injury, Sambé decided to spend his time meeting new people, to help a wider audience connect with the medium of this dance. Desiring them to see beyond the tutus and tights, Sambé discusses the responsibility dancers have to truly engage with the universal stories told within ballet. “Some ballet dancers still want to look like this idea of the perfect ballerina, like they came out of a music box,” he tells me, “But you can’t tell real stories and truly understand the complexity of a character if you’ve spent your life in a perfect tutu.”

As an artist Sambé is embracing his own vulnerability, and he urges other dancers to follow. Below he also discusses the long-awaited need for queer ballets, the relationship between dance and cinema, and preparing for his role as Des Grieux in Manon, which he will soon be premiering on opening night at the Royal Opera House.

Allegra Handelsman: Growing up in Lisbon, you started your dance studies learning African dance at the local community centre. How much influence does this style have on your performances today?

Marcelino Sambé: My point of view is quite unique because I did have that background, and I found classical dance through such a weird medium. When I’m thinking of dance, especially classical dance and the classical world, I see it from a different perspective because I’ve been exposed to a completely different way of presenting art and dance. But I’m only now realising how interesting that background is for me. When I was younger I thought it was hindering me, because when I started learning ballet at 10 or 11, I was behind, since I’d only studied African dance. My muscles were different, my way of listening to the music was different but as I grow, I understand how lucky I was to be exposed to this style of dance.

AH: You have previously played Crown Prince Rudolf in Mayerling and Romeo in Romeo and Juliet. When tackling these incredibly dramatic rolls, how much do you view yourself as an actor as well as a dancer?

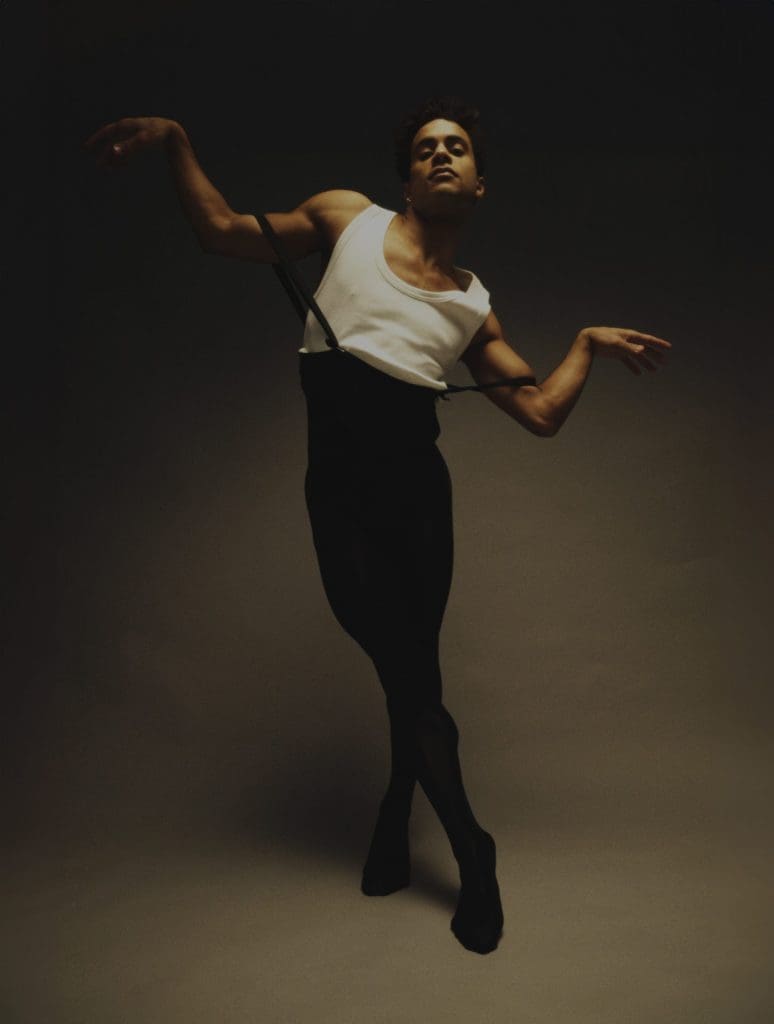

MS: When I was in America as a kid, I saw a couple from ABT [American Ballet Theatre] performing Romeo and Juliet, the balcony scene and it blew my mind. Until then, I thought ballet was just the Russian take of ballet, which I love, but I always thought it was just this classic style, so I was more inclined [towards] contemporary dance. But when I saw Kenneth MacMillan’s balcony scene, this couple intertwining, bending, kissing, being emotional and telling a story, I realised this is what I wanted to do. It’s the perfect compromise between classical and contemporary dance.

In ballet you have to trust everyone around you and you have to relinquish a lot of control, which is what acting is really about. I really dislike performers who come on stage and there’s a heightened energy around them. It’s not real, it’s not human, we’re not superheroes. Even if you’re playing a fairy, there must always be a human on stage.

AH: Your next role is as Des Grieux in Manon, which you will be debuting at the Royal Opera House, on opening night. How does this character differ from the others you have portrayed?

MS: I’ve been reading the book, Manon Lescaut, which is all through my character, Des Grieux’s eyes, we never hear anything directly from Manon. He creates this amazing picture of her, which has informed me already how I want to play it. So far, I think it’s one of the most complex roles I have taken on. What makes him different from the other characters I played is that he’s completely uncorrupted at the beginning. Des Grieux has this beautiful and poetic energy, but Manon corrupts him in so many ways.

AH: Manon, based on the 1731 novel Manon Lescaut by Abbé Prevost, was composed by Kenneth MacMillan in the late 20th century. How much relevance do you think the story has in contemporary culture?

MS: When we talk about Manon, we see this woman battling with the idea of ownership. Women at the time, they had no control of their own money, they always had to find someone else to provide for them, even if they were the ones with the riches. Although it’s not as binary anymore, this idea of ownership remains a struggle for women. But also, the themes of love, obsession and possession are timeless. Ballet holds a mirror to society and Manon is torn between glamour and love.

AH: You and Francesca represented the culture of British ballet by dancing at the King’s Coronation Concert. (I don’t want to define you by labels) but as a Portuguese born, gay, black performer, when given such an incredibly large platform, do you feel an extra level of responsibility?

MS: Absolutely. When I was chosen to do this, I was mind blown, thinking about where I came from. It was personally such an achievement. Especially, performing in a country which is facing more and more political turmoil, with Brexit, I felt like I was representing so much more than just ballet. I was representing all the amazing workers who came from outside of the UK to find a better life.

AH: Traditionally ballet is an artform based on uniformity. There are many who believe, partly because of this, that there is a lack of diversity, ingrained in the culture of ballet. It’s still difficult to find ballet slippers or tights, that aren’t pink to match white skin tones, for example. Would you agree that the industry itself needs to prioritise diversity more?

MS: I think it’s a conversation which is so ongoing, it’s a conversation which has fallen onto the management [of the ballet companies] but actually I think dancers need to be part of it as well. What I’ve seen is that dancers are coming up to management with their own thoughts on this subject and management are happy to listen. In the Royal Ballet at least, I feel the director of the company Kevin [O’Hare] was always choosing me because of my talent and my identity never hindered me. I think more management are starting to embrace the background of their dancers, which means that there is some really exciting talent coming out of ballet schools. We are now slowly seeing these changes creeping in, which I think is incredible.

AH: What changes do you want to see in the industry?

MS: A difference I would really like to see is how dancers are perceived outside of the theatre. Some ballet dancers still want to look like this idea of the perfect ballerina, like they came out of a music box. But I want to show how dancers are complex creatures, we’re artists. You can’t tell real stories and truly understand the complexity of a character if you’ve spent your life in perfect tutu. I think there is a naiveness to this idea that dancers are special beings, for me there is nothing more perfect than vulnerability, imperfection and raw emotion. There needs to be more people in the ballet industry who really know the world, people with political ideas with a clear vision of what art really is.

I think there is a naiveness to this idea that dancers are special beings, for me there is nothing more perfect than vulnerability, imperfection and raw emotion. There needs to be more people in the ballet industry who really know the world, people with political ideas with a clear vision of what art really is.

AH: In a recent interview with The Times, you questioned why there were no original queer ballet stories. As a gay man yourself, is performing a queer story something we can expect from you in the future?

MS: I think queer ballets are so important. This world has been composed by so many incredible queer people, and we need more representation of this on stage. I think ballet would be the perfect medium to tell queer artists stories.

My dream is to choreograph and produce this idea I have for a ballet; I’m consumed with vivid dreams about it. I want to tackle the life of Tchaikovsky, not just because he was such an influential artist but [because of] the way he connected his life to his own creations. When I’m listening to his sixth symphony for example, that’s his suicide note. When he created the Nutcracker, his sister had just died, and the pain in the music is so extreme, when I’m performing it, I know I’m in a world of sweets, but the music is a sad, dark outcry of emotions.

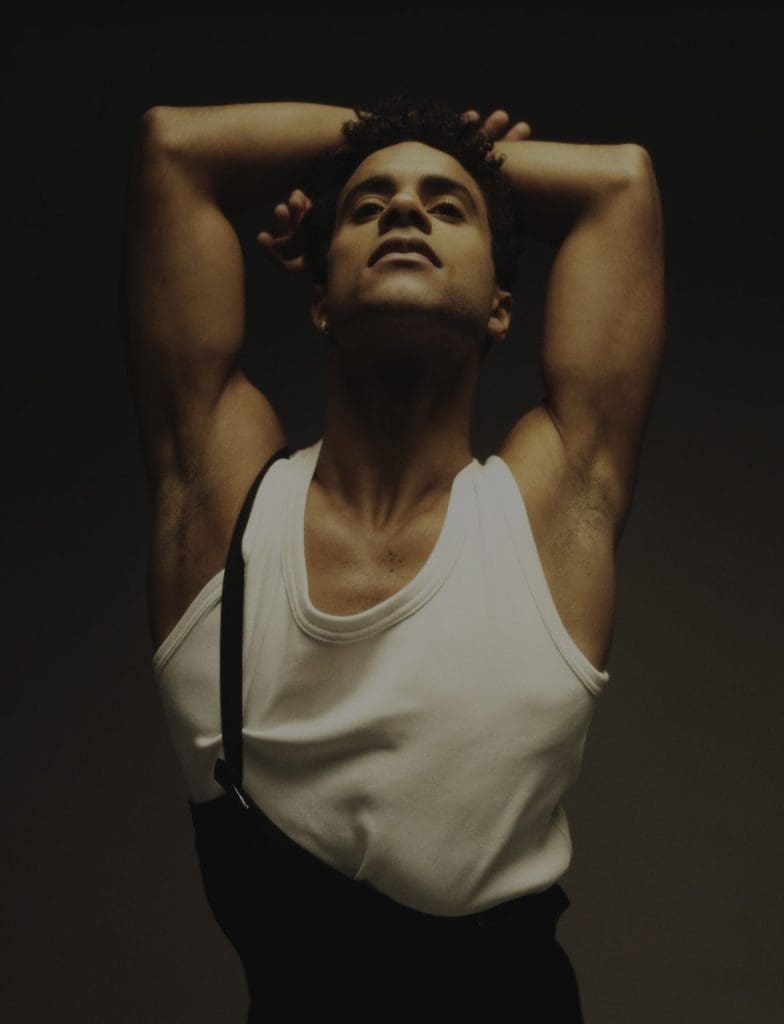

Marcelino Sambé photographed by Stanley Dunmore

Marcelino Sambé photographed by Stanley DunmoreAH: You recently suffered from an injury, which meant that you could not perform for a while. Did your view on your performances and the world of ballet change during your time off?

MS: I’ve had two major injuries, the first when I was young, and I was off for nine months. It was such a terrifying time in my life, because I had no perspective on the situation. Since I was focusing on my sadness, I gained very little from my time off. This time when I was injured again, I sprained my ankle, I decided that I was going to make the most of my time off to meet people, to understand more about what I want to do with my life and to gain more perspective on the world. It was a beautiful time. Since then, I’ve had a rebirth, a renaissance and now I’ve come back to dance, I’ve been enjoying it so much more.

AH: If you could change one thing about the public’s perception of ballet. What would it be?

MS: I think people have a preconceived idea of what ballet is, they need to look past the tutu and the tights and really understand the universal stories we’re trying to tell. It’s still a very niche art form and for me when you’re in the ballet world, you forget that some people find it weird. Watching a ballet is a fleeting experience, and because of this, it’s hard to connect to a wider audience. Cinema is an amazing medium to do this, but it will still only attract few people, because it is not a popular or commercial art form, it’s delicate.

AH: Ballet is a medium often depicted in film. Personally, for me, 1948’s Red Shoes or Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan come to mind. Are there any pieces of ballet cinema which have inspired you?

MS: I love Pina, it was a film which really influenced me, since she was one of my favourite artists. But, in general, I’m really influenced by cinema, going to the cinema is one of my favourite things in the world. I’ve watched Saltburn three times, I can’t get over it. I’m curious about cinema as a medium, and I’d love to be part of it in some way. I’m so drawn to great performances, the way actors can melt into the screen and become real, I think screen acting is something I can connect with for my stage performances. In the future, I’d love to choreograph films and help actors move better.

Marcelino Sambé will play Des Grieux in ‘Manon’ on 17th January and 17th February at the Royal Opera House.