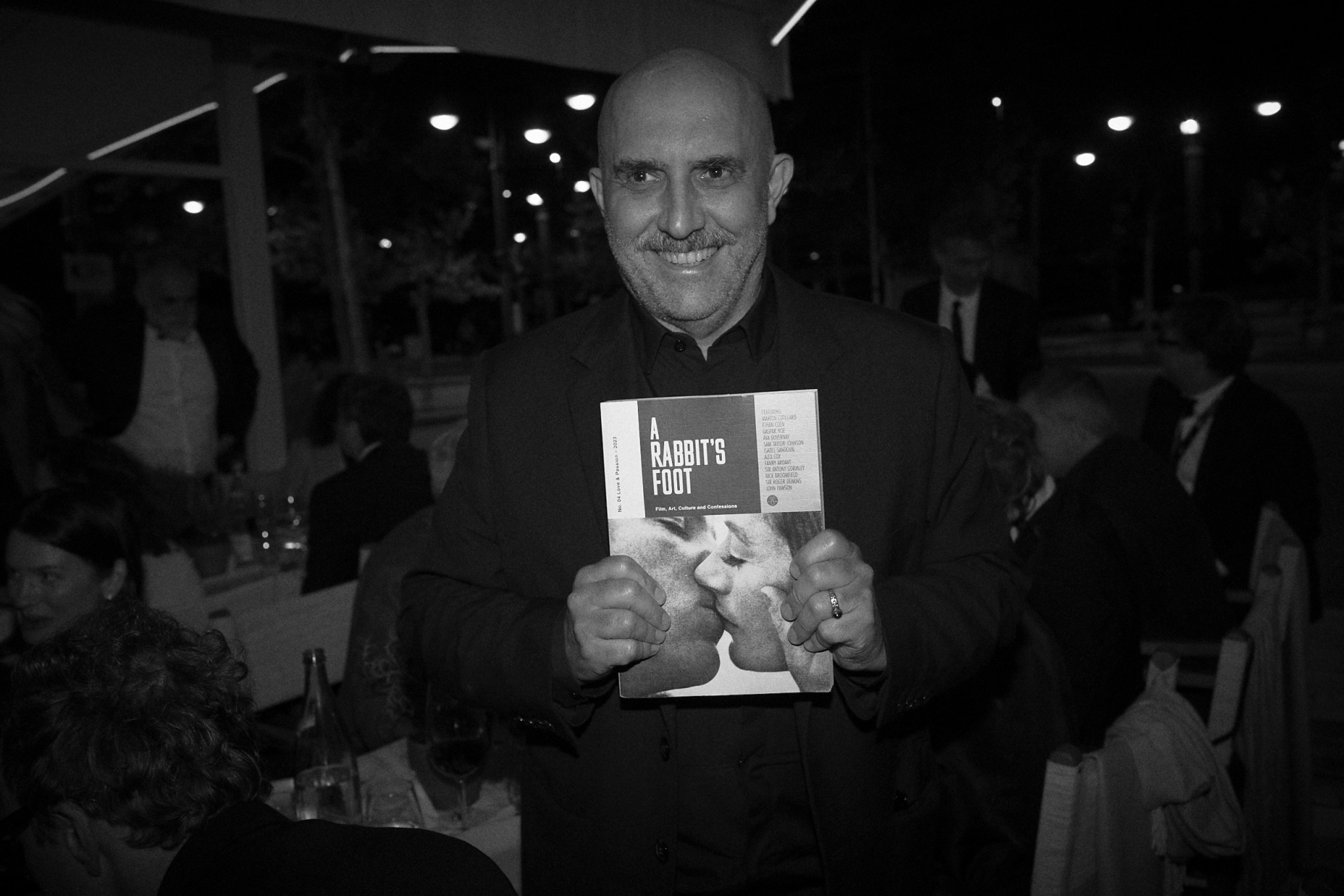

A hop and a skip outside of the Croisette is Fred l’Ecailler, one of Cannes’ most enduring hidden gems and a favourite during the Festival. Run by Fred Garbellini—a man who comes straight out of the movies—the restaurant is where A Rabbit’s Foot hosts Charles Finch’s Filmmakers Dinner each year.

On a few occasions in Cannes, I’ve dragged myself away from the festival and the gruellingly busy Croisette, and sought to step outside of the circus. Where do you go to breathe during an international film festival? And then, where do you go to eat and drink well? The industry types and film journalists are known to check in

at McDonald’s or procure a €15 croque monsieur at one of the brasseries. But a little way over, on the flat seaside stretch toward Antibes (wonderful Antibes), is a stretch of respite by Palm Beach where kiosks sell delicious and traditional pan bagnat sandwiches moistened with olive oil, tuna, and the juices of diced tomato. It is also where the best restaurant in Cannes is located.

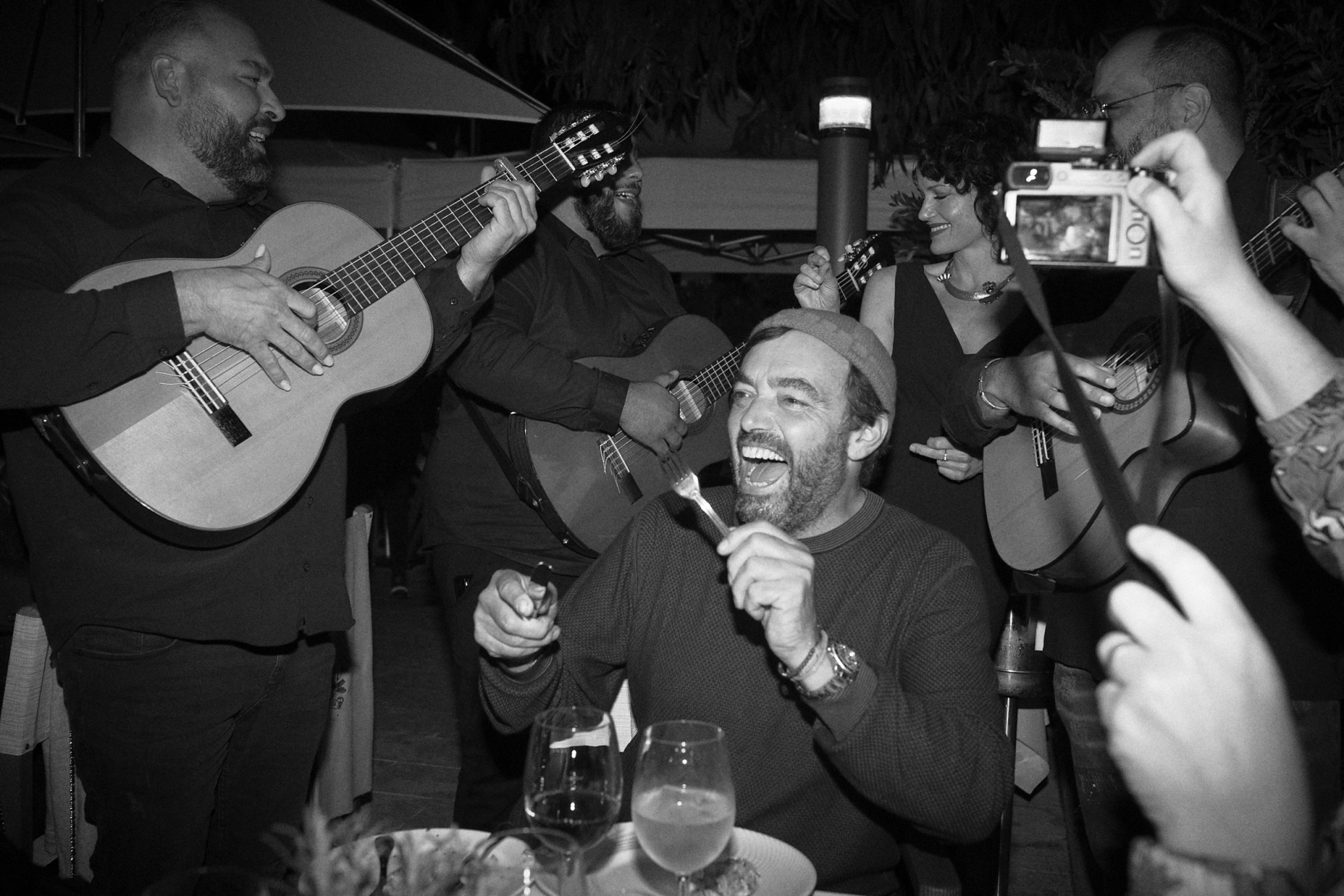

Fred l’Ecailler is on the Place de l’Étang, a quiet square characterised by the large pétanque pitches. From morning to sunset, at a restful pace that contrasts with the Croisette, groups of men play boules. In the evening, the place lights up and the nighttime is punctuated by sounds of the restaurant’s happy guests; the fairylights and the unintrusive white-shirted waiters wandering through the salon, gracefully manoeuvring with platters of freshly caught fish and corked bottles of chilled rosé wine.

The restaurant has been in operation for 28 years. Something about the lingering dust from the petanque court mixing in with the hot evening air, the scent of geranium and lavender from the gardens, is always intoxicating. It’s nice to be away from the Croisette, and it is especially pleasant to be away at Fred’s.

There is also Fred Garbellini himself, the great captain of this enterprise. He is a local celebrity, as much a part of the Cannes festival experience as the stars who gather here, and fashion houses continue to arrive at this small fish restaurant to host their grand parties (as well as A Rabbit’s Foot). I have never seen him wear anything but his striped marinière and red beanie hat—a uniform that reminds me of a sailor from Marcel Pagnol’s Marseille movies or a character from a Tintin comic. It’s hard not to imagine Garbellini in another time as a salt dog pirate. He has a black beard and is always ready with a roguish quip. Garbellini likes it when you order beer instead of wine, and especially if it is a bottle of 1668: “French beer!” But he is also completely no bullshit when it comes to stupid questions or requests; sometimes to the point of aggravation for the more overly pampered guests (I’ve been on the other end of it).

For many years, our editor has hosted his filmmakers dinner with Garbellini, and the pair have developed a friendship— and a mutual respect—that is built, I think, on a love for the sea; of sailing boats, and of a firm handshake and sharp replies. During a brief discussion, I spoke to Garbellini and asked him about his restaurant; a place preserved in the hearts of everyone who has paid a visit. Particularly the late Jean-Paul Belmondo, who was a regular, and who arrived shortly before his death.

“Managing a restaurant is, above all, a story of willpower, tenacity, and raw courage,” Garbellini explains to me. “It’s not always about studies; sometimes it’s a door that opens when others are closed. When you have the opportunity, you respect it. You cling to it. You give it your all.”

When I ask him about being a restaurateur, he replies, “I’m not a restaurateur. I don’t identify with that word.” For Garbellini, it smacks of management, schedules, and bills. “What I do is something else,” he says. “It’s a handful of passion. A visceral connection with the sea. Fish, for me, isn’t a product: it’s a language.”

It comes from Garbellini’s childhood. Even today, he regularly heads out on fishing boats for his catch, or purchases directly from fishermen: “I grew up with salt water in my veins, with respect for what the sea gives and takes away. I treat every fish I serve like a gift. My greatest pleasure isn’t filling a room. It’s seeing a sparkle in a customer’s eyes—that suspended moment when they realise they’re experiencing something unique. The right flavour, perfectly cooked, an almost invisible detail that makes all the difference. That’s my challenge with every service: finding the little magic that keeps eyes red. Bright. Alive. It’s not cooking, it’s alchemy. A quest. A form of poetry without a pen. So no, I’m not a restaurateur. I’m a sea lover who tries, every day, to share a little of that beauty on a plate.”

Polish poster for Purple Noon (Plein Soleil, 1969). By Bohdan Butenko.

“Desire is what transforms a dish into a memory, a service into an experience. Without desire, you might as well be selling nails.”

“Desire is what transforms a dish into a memory, a service into an experience. Without desire, you might as well be selling nails.”

Fred Garbellini

In the main dining room, I ask about a wood-carved model of a ship,which is treated with reverence by Garbellini and his team, and is rarely ever moved around for the sake of accommodating more seats. “This is a Thai boat,” Garbellini explains proudly, before leaning in and pointing out the intricate details that keep it afloat and powerful. I imagine Garbellini on that boat, shouting expletives to his crew. But the crew is also a family. Every year, I see the same faces; the same waiters, barmen (especially the kind gentleman from Mexico, who always allows an extra beer or glass of wine after hours), and chefs. “Surrounding yourself with real people creates a mini- family under pressure,” Garbellini says. “It takes trust, respect, and strength. Egos stay in the kitchen; the speed bumps are managed together.”

Like I said, in another life, he was a buccaneering leader of salty dog sailors. His kitchen is run like a brig. The captain is firm but well-respected. Garbellini explains his motivation like this: “Desire is that crazy driving force that makes you get up even when you’re tired. It makes you smile when you’re exhausted and makes you welcome each customer as though they were the first. Desire is what transforms a dish into a memory, a service into an experience. Without desire, you might as well be selling nails. It’s a profession of giving, not a career plan.”

So how did this small, unassuming fish restaurant become such an institution? “It’s about being clear about your numbers, your flaws, your limitations. It’s not a profession for dreaming with your eyes closed; it’s a profession for moving forward with your eyes wide open. And knowing that every day, everything can stop if we let up.”

Everything stems from simplicity, he says. It’s what hits the mark: “It leaves space: for imagination, for desires, for memories. A dish, when it’s sincere, awakens old memories—childhood, a corner of a table, a forgotten smell, a moment that returns without warning.”