Our Editor-in-Chief introduces our tenth issue—a celebration of the word in all its forms.

Los Angeles, 8th January 2025. As I write this, many parts of the city of Los Angeles are still burning. If the fires continue to burn, it is likely to become the worst urban fire in the history of the United States. Many of my friends and our readers live in the Los Angeles area and I personally feel very much part of that community, having lived in the city for over 10 years and having worked in Hollywood for more than four decades.

I arrived in my 21st year. I had a tiny 21st birthday celebration of pizza and champagne with my mother in a small room I couldn’t afford at the Chateau Marmont. This was, of course, way before André Balazs’ ownership of the hotel and the present refined, frayed coolness of the place. It was plenty refined back then too, but only cool in the eyes of fading stars, penniless newcomers, and a contingent of ladies of the night regulars, who on occasion lent me money.

I arrived in Los Angeles as a grown up, then: all of 21 with $1,500 in used notes in my pocket to join my mother Yo Yo, who was pursuing her dream of becoming a screenwriter and winning an Oscar. Her circumstances, financial and health-wise over the decade prior to her coming to Los Angeles, deteriorated to the point that she was now reliant on me for financial support (no wisdom in that), and vodka and valium were unfortunately her other crutches.

Born an heiress, married to and then divorced from my father Peter Finch, one of the most important matinée film star idols of the 50s and 60s, her fall to penury—to poverty—had been great and indeed fast. And yet, her passion for writing and the ruthlessness of her pursuit of a career as a screenwriter, at the cost of her social circle—who didn’t understand her vow to poverty, if it took that to succeed—was unbridled by any sort of shame. Even as her material life and mental health were destroyed in equal measure, as a result of what became her obsession, she continued each day to write from the crack of dawn, cigarette between her teeth; the booze locked up until that first drink at noon.

Issue 10 — order now

That writing—the power of the words and the word in any form to her—became her true opioid, her drug of survival, her raison d’être. For my mother, writing was both a necessary physical function and a cerebral lifeline to a creative dream which never materialised. It reminds me of what Trigorin replies to Nina in Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull, when she suggests his life is beautiful.

Trigorin: “I see nothing especially lovely about it. I must go at once and begin writing again. I am in a hurry.”

The full quote is essential in understanding both Chekhov and writing. And many great writers express this physical need, as Trigorin does, to get the words out of their bodies. A writer must write or die. The case of my mother was extreme: her madness and obsession with winning an Oscar limitless, and her successes too small, as she drowned in unfinished projects—in the requirements of a quotidian life she couldn’t manage and in the bottle which she needed and despised. She had asked Lawrence Durrell years before at one of her wonderfully wild parties what he did when he wasn’t actually writing: “I box naked in the dark,” he told her. Yes, he too, this sublime wordsmith, wrestled to keep the demons away and to get the words out. From my earliest memories, my mother’s fascination with the poetry of words was a constant in my life. The way she spoke—her wit coupled with her beauty, and her bedroom knee-high in books—is how I remember her best, and for the combativeness of her quest to finish a sentence properly, or to craft a paragraph or a piece of dialogue. The writers among you know what I am talking about. That she chose Hollywood as her final battleground was not by chance. She saw film as the sublime form of communication; the visual and the spoken word combined in exquisite form to tell a story in the most powerful way, and of course, if you believed this, then there was no other place for it than the Hollywood of those days; a time when the studios still made ‘grown-up’ films. That Hollywood is the reputed cemetery of writers didn’t cloud her dream—as it didn’t mine and still doesn’t. It still starts, after all, with a story and a script.

I wrote two films with my mother, both of which I directed, and a third film which we made with my friend Al Ruddy, who died last year. Her influence honed the fire I had inside me to write. I too held onto the dream that I would write a great script, and at the very least, a novel one day. And it was writing that paid my bills in the earliest days of my career in film. We would meet early in the morning and work on the pages either of us had written the night before. I ignored that she had no life other than this (or if she had a life outside of this work, I was unaware of it, as I too was obsessed with the work). It sustained us both. It fed us both. I would sell an idea and we would write it together, living as we did, script to script. Looking back now it breaks my heart that I never thanked her enough. She never had the success she deserved, as she wrote so well, especially brilliant in turn of phrase.

As she lay dying in a public ward in London, she made me promise to get her film, Lisa’s First Orgasm, made—a challenging task to say the least—and to win an Oscar. And finally, she asked to have her ashes spread on the Blue Mountains. None of these have happened yet, but rest easy—I have a plan.

Charles Finch’s mother Yolande Turner, 30th December 1963. By Albert McCabe.

I am choosing to talk about writing in Hollywood to best illustrate not only my love of the written word but also the “word” itself as the starting point for artistic expression, which even today has not changed. Like Sisyphus, screenwriters push a project up a hill, then as it rolls back, they push it up the hill again. Writers of novels and plays are equally consumed with their craft and use of words to tell their stories, but film writing is more complex not only for the technical requirements but also for the lack of industry acclaim. It is why the WGA exists to protect the screenwriter.

In this, our 10th issue, we celebrate THE WORD itself with the inclusion of some of the great artists of our time, from writers and their stories to filmmakers and artists from around the world, and how they use the written and spoken word.

In London, I spend time with Sir David Hare, who talks of the early days with Film4 and his adventures from when there was an open checkbook to make experimental and socially impactful films. He is one of our greatest writers of contemporary drama, and also a poet and director of film and theatre, and we are honoured to have him in our pages. Photographer Laurence Hills candidly captures Hare at home in his study.

My deputy editor Chris Cotonou interviews the whirlwind of talent that is Jeremy O Harris. In New York, photographer Max Montgomery and our creative director Fatima Khan captured his spirit. Known best for the acclaimed Slave Play, he is a prolific and enchanting force of nature. If you don’t know his work, you will now.

From Tokyo, we bring you to Asako Yuzuki, the author of the bestseller Butter. As her fame increases, Yuzuki discusses her work and the tribulations of female writers in Japan. Continuing our journey around the world, we also introduce you to the Greek writer Efthimis Filippou, a long-term collaborator of Yorgos Lanthimos (who photographs him here) and one of Greece’s most important cultural voices. Filmmakers in this milestone issue include Edward Berger who writes to us of his use of the dialogue and silence in his films, notably from his brilliant film Conclave. Steve McQueen brings insight to his work on Blitz’s release. McQueen’s intense honesty and focus brings unyielding power to his films. His fearless observations keep our features writer Luke Georgiades on his toes. The master filmmaker Jacques Audiard joins us on the release of Emilia Pérez. His films re-invent storytelling and he is both an elusive, but present, and graceful genius. Discover here Halina Reijn, in a truly personal portrait by Kitty Grady, and watch her Babygirl. We are privileged to include Denis Villeneuve who is, in many ways, the Kubrick of today, allowing a vast canvas to somehow feel intimate.

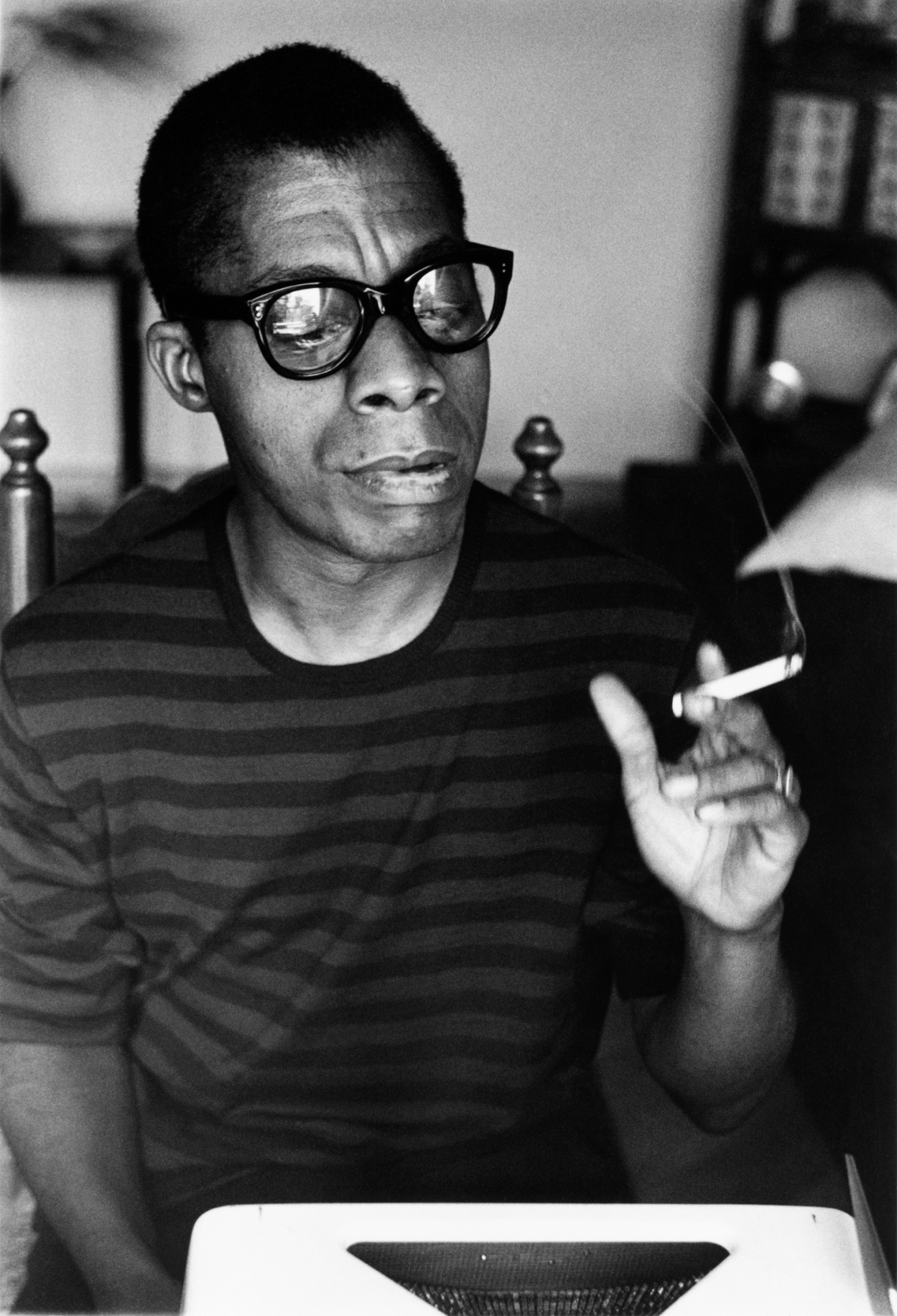

James Baldwin working on his typewriter in Istanbul. 1966. By Sedat Pakay.

What better way of illustrating the writers’ work than through the actors’ use of the word itself? To this end we chose four great actors of the screen and stage: Dame Judi Dench at home by Natasha A Fraser. Dame Judi allows us access to her country home and a glimpse of her life and stagecraft, at which she has no peer.

Dame Harriet Walter, another legend of the stage, graces our pages with humour and restraint, and she teaches us. Literally. And we have chosen Felicity Jones as our younger voice from the theatre and film, not only for her breathtaking performance in Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist but also for her translucence and her underlying grit. Our final actor is the great Adrien Brody, who time and again surprises and surpasses with the depth of his performances and his risk-taking. Brody’s performance in The Brutalist is one of the most important of all time. I went to see him perform at the Donmar, removed from the growing acclaim of The Brutalist, on the small stage night after night.

We include a conversation between sensational young director Brady Corbet and his friend, emerging director Fridtjof Ryder. It is an intimate piece, and a way of gaining insight into this brilliant filmmaker’s world that would be unique. If you have not seen The Brutalist, then please do. I tip my hat to Corbet’s bravura and talent. In our essay section, Elisabeth Robinson writes an extraordinary long-read on Hemingway through the eyes of Lillian Ross. We also include Daphne du Maurier’s love of Menabilly, written by Issy Carr from Rabbit’s Foot Films—a poetic piece that made me want to up sticks immediately and head to Cornwall. There is poetry from Imogen Lycett Green and art essays on Glenn Ligon and Lee Friedlander. There is much in this issue that I have not mentioned. After all, it is for you to discover. As we turn 10, we look ahead to 2025 full of hope that we can bring you more; that we can further grow. We have many plans for this year. Stay tuned.

Thank you for being part of A Rabbit’s Foot. Thank you, Team Rabbit, as ever.