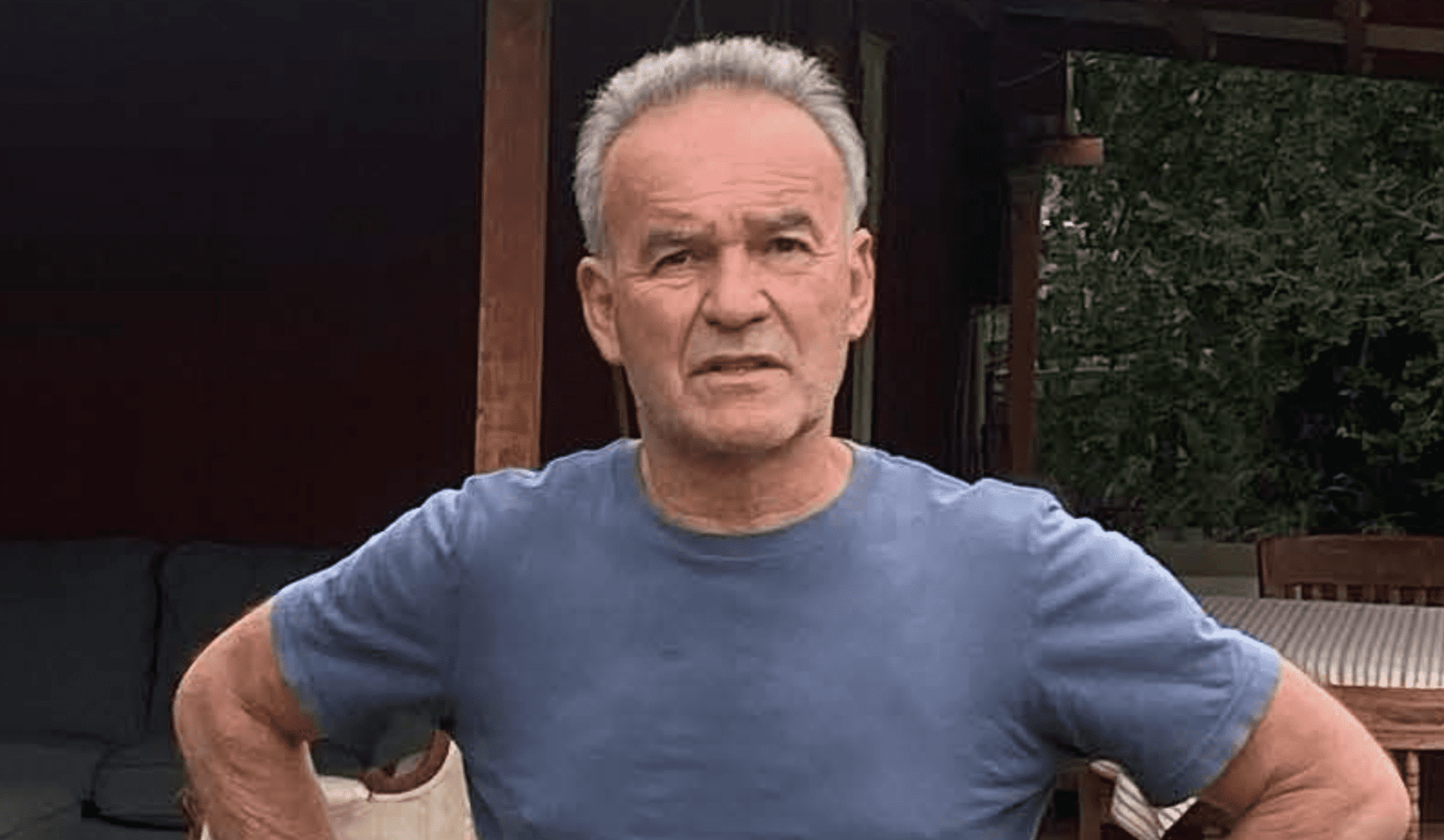

Nick Broomfield is one of the most extraordinary documentary filmmakers working today, having made over 30 films, many of which are classics; and all with a style and methodology often now emulated by younger documentarians.

But we couldn’t really praise Nick without being honest: we’re a touch biased; or just moved. A RABBIT’S FOOT editor Charles Finch is a close friend of Broomfield—he might even love him like a brother. Because Broomfield’s obsession with finding the truth, making the interpretation his own, and then ours, through an intimate excavation of his subjects, really does make him consistently unique in his artistic portraiture.

Relaxed by a park bench in London, Charles Finch talks with his old friend Nick on the meaning—and price—of truth…

You’re in your mid-70s, and you have had immense success in your life as a documentarian, creating your own style. And we were talking this morning about the challenges of making modern documentaries. Why is it so difficult now compared to how it was before?

Looking back I was very fortunate to have grown up with Channel 4 and the BBC. There’s a tradition in England of broadcasters basically looking at themselves as publishers. They publish an author’s work. The attitude of the streamers now is that they’re a studio, and they commission people to make their films, which they will then own. With the BBC and Channel 4 it has been possible to retain one’s own copyright and ownership of one’s work. That has completely disappeared now. It’s a different relationship, and the director is not particularly respected. Obviously it’s handy if you’ve got an Oscar. But the streamers have very particular things that they want—what with the algorithms and everything. They’ve taken over creative control of the kind of films that are being made.

But from a freedom of speech point of view, say I was to make the Nick Broomfield story as a documentary, presumably you would want to exercise some sort of editorial opinion and control over this piece which is about your life…

Not really because I’ve already submitted myself to a couple of crazy films where people would appear at my parents house and ask them a lot of inappropriate questions about me. Part of the joy and the wonder of journalism is that you do an unauthorised piece which contains the truth of somebody who hopefully is fair and impartial, which means you create an honest portrait of how they perceive the subject.

What is the truth to you?

I think when I started there was this so-called notion of balance that you gave both sides of the argument and somewhere in the middle was truth, which made for pretty boring films. I always felt that there was a subjective truth. There’s your subjective truth and as long as the audience understands that it’s your view, that this is what you believe, then I think that’s fine and they can take it or leave it. I think when you pretend that it is THE truth, the universal truth, and you assume Godlike properties, then there’s a problem.

That really sums up your work; there’s always an interpretive aspect to it. By so often putting yourself in the films, it feels clear to people that it is subjective.

Exactly. I was very lucky that I grew up under the influence of people like Tom Wolfe. The experience of making a story or writing a story was often as much an intrinsic part of the portrait as anything else. There’s the famous story of Frank Sinatra having a cold, and this writer goes out to interview Sinatra and is continuously put off by excuses that he’s not available or very busy, and in doing that, he reveals this amazing entourage of people surrounding Frank Sinatra and the complexity of his life around Palm Springs. What emerges at the end of it is that he had a cold and no one dared tell the journalist. It’s a brilliant portrait of the world he inhabited.

Out of your 36 films, what is the most important one to you emotionally?

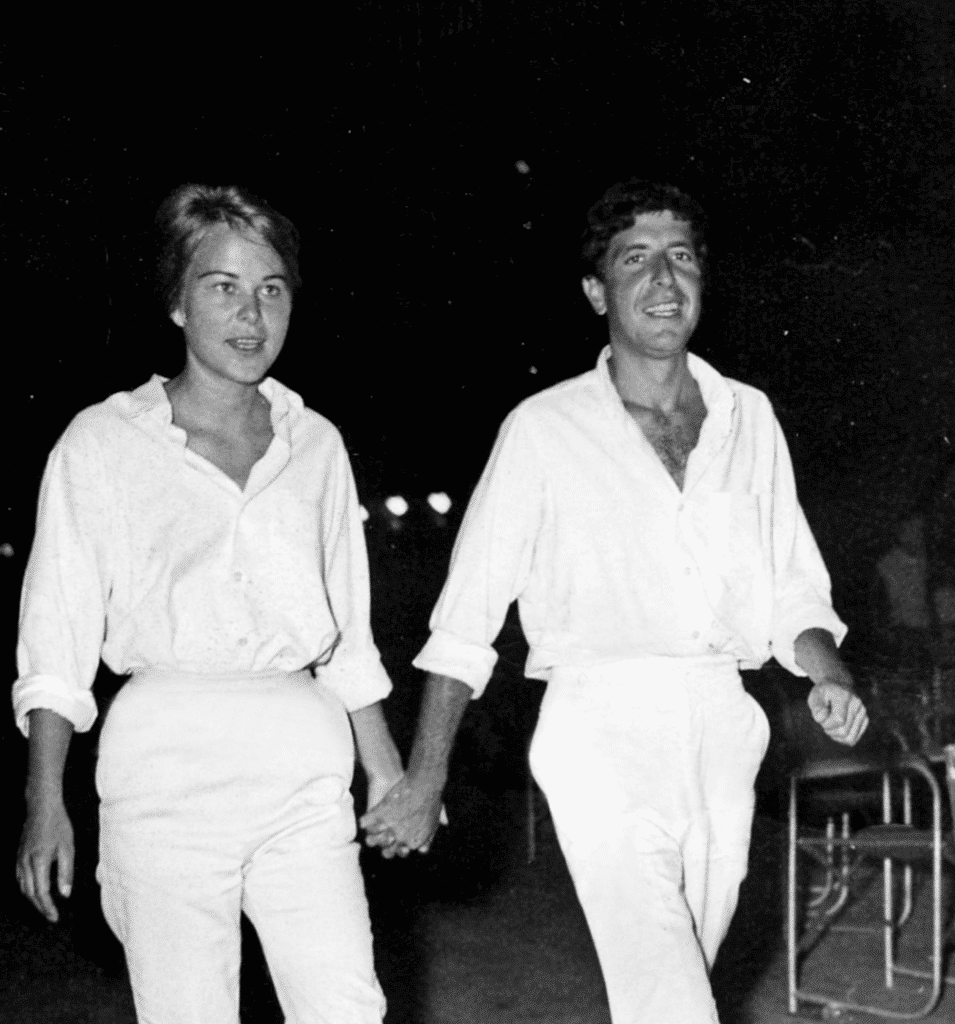

I’ve started making much more emotional films as I’ve grown older. Maybe one becomes more in tune with one’s emotions. I’m less angry. I think the film about my father was my most personal film, but I think the film I made about Marianne and Leonard was a very personal film about love.

Photography from Nick Broomfield’s personal archive.

You’ve made two documentaries about love affairs—some gone wrong—but you might think of Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love and their story as a love affair. Would you agree?

Absolutely. And Whitney is certainly about a love affair between Whitney and Bobby Brown, which obviously went wrong. I think it’s great making those stories because we’re all looking for a wonderful love affair that’s going to bring a lot more meaning to our lives and our relationships. People really identify with those stories.

In your experience making these documentaries, particularly on subjects that you get to know really well, who moved you the most?

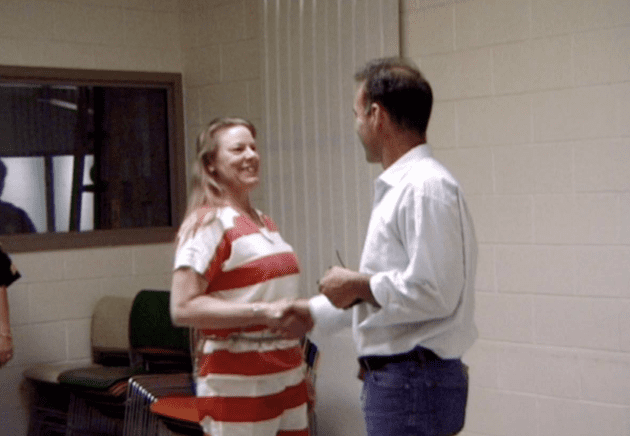

Curiously enough I was very moved by Aileen Wuornos, who I made two films about. She was a hitchhiking prostitute who had had a pretty awful life and ended up killing seven of her clients. I went to see her at a prison—the Broward Institute in Miami—and we struck up a weird relationship. I don’t know why but she thought we were a rock band who had come to perform in the prison that night. I think it was handy that her lawyer had only ever represented pot smokers, so he had a lot of marijuana on the way down to the prison, and when we got there we did a very foolish thing which was drive round the perimeter filming, which we probably wouldn’t have done if we weren’t sucking up fumes the whole way down. We got arrested by the prison guards and strip searched, and the rumours of us being strip searched were going round the institution.

Aileen just thought we were wonderful. I kept saying “we’re not a rock band, we just did a stupid thing” but we had this relationship for about 14 years. And when she was finally about to be executed and I was called as a witness to testify on her behalf, I realised that over those years we had written to each other backwards and forwards. I had found out so much more about her upbringing, how she had been raped by her brother and her grandfather, who she also thought was her father, and how she lived feral in the woods for quite some time and absent from school. In America there’s no real social services so no one was even aware of what she was going through. She grew up in this weird way, and ended up falling madly in love with another woman. She felt she was going to lose this woman because she couldn’t support her anymore…

I think her first murder was in self defence—a man called Richard Mallory, a known sex offender, was abusing her and had her handcuffed to the steering wheel of a car. And she managed to get his gun and shoot him, and then robbed him as he lay dead. I think she got into the habit of killing and robbing.

How many men did she kill?

Seven.

And were they all in similar circumstances?

Some of them were just Honest Johns who picked the wrong woman when she had lost her mind.

When you had spent time with her in prison did you feel as if she was sane?

I thought she was very schizophrenic. She thought her mind and her thoughts were being controlled by the prison comms. She thought she was going to be beamed up like in Star Trek. I filmed the last interview before she was executed and she didn’t understand anything, but she wanted to be killed. Jedd Bush was the governor of Florida at the time and he was running for re-election, and [Aileen] was hated. There was no way she was not going to be executed. She just avoided the electric chair—it was injection.

Did you watch it?

I didn’t want to have that imprinted in my brain.

And what did it make you feel about capital punishment?

I felt if it had been a caring society, they should have looked into why she was truant from school all these years and why social services were so absent…how that was possible that somebody could have had this unbelievably awful life that somehow fell through the cracks. But America isn’t interested in that sort of thing, the thing that was most upsetting was the feeling of retribution and vengeance. Prison guards clearly hated her.

Why?

They thought she was nuts, which she was. They came out with all these weird thoughts, and I remember them rolling their eyes and smiling at each other, because she was saying things that were clearly deranged. But at the same time they were going to execute her. She was frightened to go out into the exercise yard because a lot of other prisoners taunted her. She used to stay in her cell and write these amazingly long letters to her friend Dawn Bobkins and she did these incredible drawings that Dawn has. I did feel that Charlize Theron got a certain sense of her [when she played Aileen in Monster].

Who portrayed her in Monster. Did Charlize ever get in touch with you about her?

I gave Charlize quite a lot of the footage I had so she could base her portrait of Aileen more accurately. I felt the biggest story was “what created Aileen? The remedial things that should have happened in a more caring society never really occurred. So when she was executed it was devastating to me on so many different levels. We all went to Cumberland Island immediately after the execution, and it was kind of like grieving. The lack of concern and the glee with which most of the other newsagents covered it was pretty disillusioning.

Did she scare you?

Not at all, no. She had a great sense of humour. We had a good time together, and for a long time I never understood my own emotions towards her. But if I was asked questions about Aileen and I would find myself fighting back tears. I found it incredibly difficult to talk about her.

You’ve made interesting films about women throughout your career…

The woman who was most influential to me was in my first film Rent Strike, when I started film school. She was called Ethel Singleton and was a working class Liverpudlian. She really thought I was a middle class wanker but she was very fond of me. I used to stay in her house when I was in Liverpool. But she really thought my film on her was going to do absolutely no good because I was making a film about their problems, their housing problems. She was the chairwoman of the Abercrombie tennis association in Liverpool. I’ve seen her sway crowds of two-three thousand people. She thought “you’re going to make this film and then go back to your comfortable life and it’s going to make absolutely no difference.” And she would sit me down and politically educate me from her armchair.

Do you think society has lost some of its naivete?

There was an openness and an experimental spirit [in the 80s] where a lot of groundbreaking things happened, because it was encouraged. Now we’re living in a very structured commercial world with a lot of rules and regulations and there isn’t that kind of freedom at all.

It’s terribly hard now…if you want to do a documentary now you have to go through these pitch meetings. People will ask you what the end is. The whole thing about a documentary is you shouldn’t know what the goddamned ending is. You haven’t made the film, you don’t know what you’re going to find, you’re not making a piece of fiction. A documentary is unstructured, it’s a voyage into the unknown, and the film will be this incredible adventure which hopefully will be much richer than your original thought.

You may not know the end scene but you have the gist of the story.

You have a gist of the story but that all might change in the editing room and that was all quite encouraged. I always remember going in and Colin Young would say “what’s your idea Jimmy?” with this Scottish accent, and you would tell him an idea of the film you think you wanted to make, and he’d say “okay Jimmy, what’s plan B?”.

[Laughs]

He knew inevitably it would go incredibly wrong and you’d end up with something different, often much better than you imagined. But there was that interest in Plan B. That belief in the journey and that has gone now. The strength of documentary is that it isn’t scripted fiction, it should be like the wild west, it shouldn’t be structured.

Tell me about the film you’ve just made.

I wanted to do a film about the time I grew up, in my formative years in the 60s. I’ve often thought of a time when I was travelling back from school and I met Brian Jones from the Rolling Stones on the train. I saw him sitting in a first class carriage and plucked up the courage to bang on the door. He was incredibly friendly and asked me to come and sit down, and he turned out to be a trainspotter, his favourite line was the Western line built by Brunel. We chatted about that but I was more interested in all the trouble they were causing — they were our heroes because they were so anti-authority. But I was struck at how kind he was. Then he was dead seven years later. So it’s always been a bit of a mystery to me how somebody like who seemed to have the world at his feet could end up in such a mess just seven years later. It’s a look at that time — a very influential time in my life. It’s showing on the BBC May 15th. It’s called The Stones & Brian Jones.

Do you feel at peace now as a filmmaker?

One of the wonderful things about filmmaking I think is that you always feel like you’re just starting, because you’ve just learnt from all your mistakes from the last one. It’s all about storytelling, and you never get it right. So you always want to try something different. It’s a wondrous thing, and I feel incredibly lucky. I’ve never really done what anybody wanted me to do, I’ve had an incredible freedom that probably not that many filmmakers have had. I feel fortunate in that way.

What would you take down the rabbit hole?

A bottle of Courvoisier and some dry bananas.