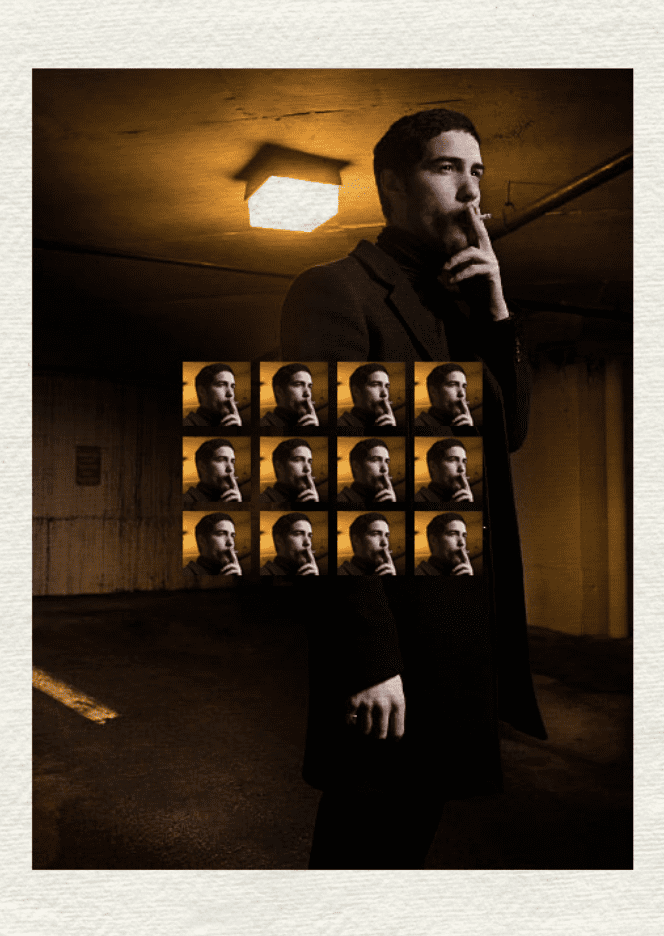

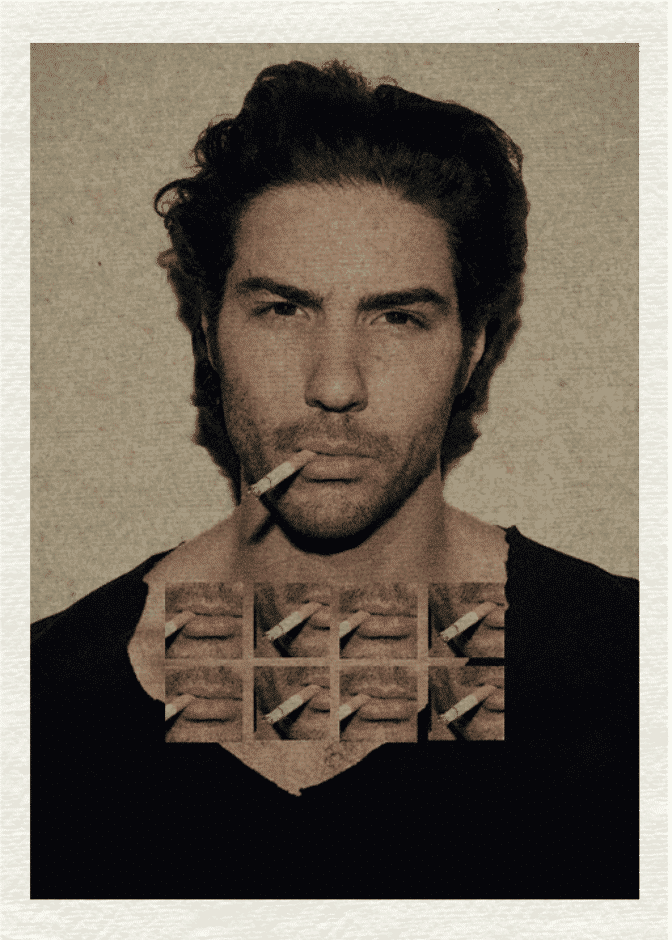

Without knowing Tahar Rahim’s biography, his origins are hard to point to on first impression. The French-Algerian actor is one of world cinema’s chameleons, having made a reputation for burying himself in a mixed-chocolate box of characters that have different motives and speak many languages. When we do meet, Tahar greets me with a gravelly New York accent. His features are Mediterranean. His clothes are Japanese. He is, of course, French—born in the suburbs of Belfort.

His career is just as varied. Rahim has played Indo-Viet killer Charles Sobhraj in The Serpent; Don Juan in Don Juan; innocent inmate Mohamedou Ould Slahi in The Mauritanian; a guilty Franco-Arab inmate in his breakout, Jacques Audiard’s A Prophet, and has finished working on Ridley Scott’s epic Napoleon, in which he plays the titular figure’s mentor Paul Barras. He speaks at length about what he has read about Barras while researching the role, drawing out another cigarette and mentioning, with some pride, the fact that his subject was the man who discovered Bonaparte. His wild fixation on whether Barras was ‘lucky or smart’ spells out his passion for getting under the skin of his characters, and it will be interesting to see what he does with the role when it is released this year.

Regardless, Rahim is one of France’s most important actors. His rise through the ranks of Gallic cinema, especially as a member of its large but overlooked North African community, is uniquely complemented by the fact that he also has a mainstream appeal thanks to his persistence in working with foreign directors. There’s the art-house credibility, too (he recently paired with enfant-terrible Serge Bozon for Don Juan), the blockbusters and the award-winning television shows, and he will be in Marvel’s Madame Web—although, he can’t talk about it yet. I ask him where he wants to work next, and he smiles and describes South Korean cinema with the same excitement as he did with Paul Barras, mentioning a new cinematic language: “It can only happen there,” he tells me, “they’re the new New Hollywood. That’s the country I want to work in the most.” But when it comes to travelling for projects these days, it’s a harder decision. “I have three kids now, and I can’t be away from them for too long.”

As Rahim begins to open up about his family and his religion, he tells me that he believes little is left to chance. He had to work his way up from the very bottom after moving to Paris as a young man in 2006, trying for roles while working at factories and nightclubs to survive. For plenty of actors, there would be a sense of entitlement at how far he has come, but Tahar is humble. He owes much of his success to his family and his faith, he says. “It’s hard to explain. I have a strong connection to God,” he adds, his warm smile making way for a more thoughtful expression, “This connection feeds me and I believe that it reminds me who I am.”

Then, as if on cue, a nearby minaret recites the call to prayer, and Rahim pauses for a second, smiles again, and adds, as if finally proving his point: “You see? Some things just can’t be explained.”

Everything else, from his first encounter with American film to his method and the representation of other Franco-Arab actors, he kindly explains for us here. This is Tahar Rahim—in his own words.

I grew up in a small town. Belfort has only fifty-thousand people and two movie theatres. They showed big mainstream movies, but not the arthouse films. On French TV channels, I remember a programme called Cinema de Minuit that introduced us to classics from around the world. But it was at midnight, so you had to be right on time—sort of like an appointment. That programme was a part of my education as an actor, and during my teenage years, I discovered New Hollywood from the seventies. I identified a lot with the anti-heroes that I would later portray. That was something I didn’t see in French cinema at the time. We’ve had no other revolution since then that has set the tone in terms of acting—that’s how powerful it was.

There’s a reason why I’ve starred in so many films outside of France. I grew up in a suburb where all cultures came together: French, Gypsies, North Africans, Africans, Arabs…you could discover all of them just by visiting their houses and having tea. You eat their food, hear their music, see different architecture or art, have conversations with them, and I’m a part of that. This is my France. So of course—because the man and the actor are linked, and because they feed off each other—to me, borders are just imaginary lines. It’s rich to discover new cultures, but I’ll admit that the languages? That’s work.

Speaking of languages, I worked on my American accent for a long time. I had to do it for my first job over there, The Looming Tower. The character is from Lebanon, but he left for the States when he was fourteen, and I portray him in his late twenties. Even if there’s a slight accent now, I chose to force it in the American direction. On The Serpent, they asked me for a French accent—but I didn’t want to do a caricature, so I found an in-between that worked. But in [Ridley Scott’s] Napoleon, they requested a British voice. It’s strange, because in that film I’m playing a historical French figure [laughs].

It’s never been a goal for me to portray real people. Films like The Mauritanian or The Serpent happened because I was pleased with at least one of three things. When I agree to a project, it depends on either the part, the script, or the director. When it’s a true story you have a responsibility…so it’s scary. But if you convey their emotion and humanity to the audience, it doesn’t matter if you’re exactly the way the subject is. What was hard in The Serpent was to understand Charles Sobhraj’s mindset, and to get into him. That was tough because I also didn’t want to meet him. Sobhraj is evil, and the fact he doesn’t have empathy…how do you create that? There’s a line in episode three that helped me get it right: “If I had to wait for the world to come to me, I’d be waiting still. Everything I ever had, I had to take it.” I connected to him at that moment. I related to that philosophy—because I had to go to Paris alone and carve my path with nobody’s help. You find one connection like this and then you have it. That’s acting.

I was surprised at how successful The Serpent was. I thought people would like it because so many streaming services have shows about criminals, but it had a huge impact. What I’ve learned is never to expect anything, or you get disappointed. I remember shooting [Jean-Jacques Annaud’s] Black Gold and that was a big flop, it was important to me and we worked so hard to make it. The marketing wasn’t great. You can’t control the success of your work, and thankfully as an actor, you can move on to the next project—which you cannot do as a director.

I once tried to write a script. But I wasn’t happy with it. If I ever direct a film, I wouldn’t be the writer. I think I was not so bad with the beginning and the end, but the body is tough. You pull a string and three others emerge. You know those big bowls with holes in them? Stop one hole and water gushes out of the other [in terms of plot]. It was supposed to be a period movie set in Paris in the 90s, during my youth as a kid, and it explored the way I would see people in the street interact.

I loved working with Serge Bozon on Don Juan. It’s an indie musical, and the challenge wasn’t the singing and dancing, but doing all of this in the strange Serge universe. He is a wild flower, his mind is somewhere else. I learned so much, because I’d never done this kind of style of cinema before. I became devoted to him, and we had an agreement: when he was happy, he would give me my own freedom in the performance. With every film, I need to feel like I have a chance to freestyle and that begins by making the director happy. It makes me feel self-confident and reassured, so I can sit back and wait for the happy accidental magic in the performance.

Since becoming a father, I’ve wanted to make more family movies. My kids are too young to watch the films I’ve starred in and I’d like to do something that I can enjoy with them. That was a motivating factor in doing a Marvel film like Madame Web. It’s also a childhood dream to be a part of that universe: this comic book mythology they have in America is something we don’t have in France. So, I never thought I’d play a superhero, as we just don’t have the same budgets as the American industry. Let me tell you, one day, I’d actually like to do a Western, and it has to be in America, right?

My childhood? I wish I could stay there forever. If only I could spend two hours a day there. I have my own kids, and although none of us are perfect, I hope I’m a good father. But in terms of love and care, their childhood is no different to mine. The difference is that they are more at ease. We didn’t have much money, and we weren’t a creative family when I was growing up. But I still rely on my family, and my faith in God to keep me grounded. My faith feeds me—and it’s always been there since I was a kid. I knew I was connected to something and I wanted to know who.

North African-origin actors are better represented than when I started out. If movies are a witness of a specific time, they have to be truthful and show these faces. Of course, I’m aware of my role in this: we share the same type of name. We show others that they can make it without being typecast—which is something I never wanted. It took a lot to not always be cast as gangsters. I’ve built a career on saying “no”. And it’s hard to say no when the siren sings. But I found my way thanks to foreign films and directors, because they approached me with different types of parts; much broader than what I received in France.

I need free time to be motivated. I was away for too long with my last projects, away from my kids and my wife…and this time in-between now is exciting, even though I have two other projects in the pipeline. The uncertainty keeps you young. You never know what’s around the corner, and it’s important to feel like you’ve never reached your goals. So I thrive in this restless, unknowing space. It makes me feel as though I am alive!