As a new season of Iranian New Wave Cinema gets underway at the Barbican, writer Sofia Hallström considers how the films—many of which were victim to censorship when they were released—have an aesthetic and political importance that is more urgent than ever.

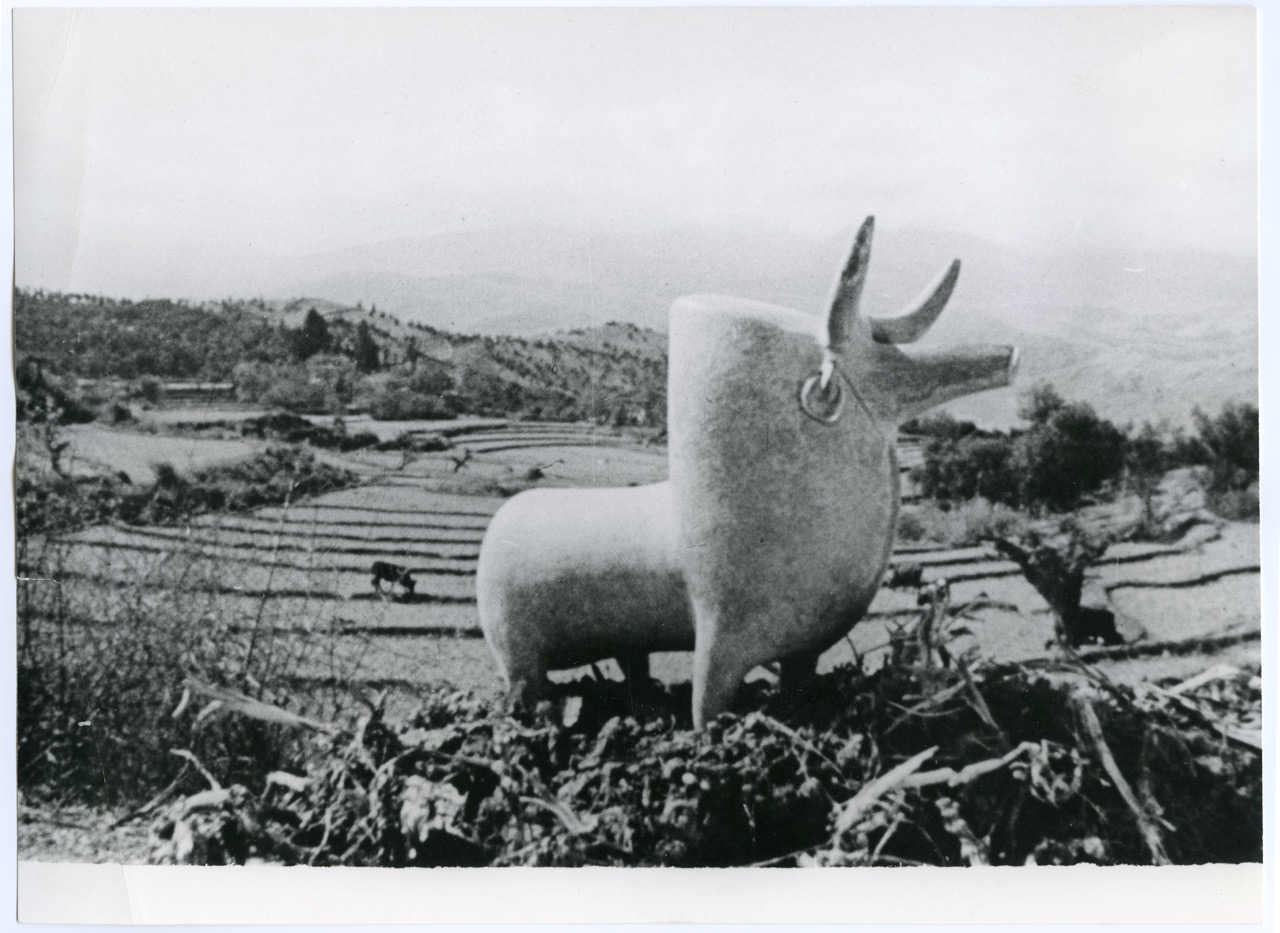

“Most of these films can’t be screened legally in Iran today, but they’ve circulated on tapes, DVDs, and now digitally. Their influence on Iranian cinema is immeasurable,” says filmmaker and curator Ehsan Khoshbakht, discussing the upcoming second season of Masterpieces of Iranian New Wave Cinema (4–26 February 2026) at the Barbican in London. “These filmmakers were making films when all the odds were against them… And some of the films in this programme have taken more than half a century to be seen in the way they were intended to be seen, or, in some cases, to be seen at all.” The programme comprises eleven titles of the late 1950s, 60s and 70s, including a world premiere and two films never before screened in the UK. Among them is Dariush Mehrjui’s The Postman (1972) which, as Khoshbakht explains, was “totally impossible to see for decades.” Best known internationally for The Cow (1969)—which was banned and later smuggled out of Iran to the Venice Film Festival where it won major critical acclaim–Mehrjui was hailed by Iran’s former Minister of Culture as “the creator of eternal works.” He was later murdered in his home in Tehran in October 2023, having just applied for a visa to attend Khoshbakht’s first curated film programme of Iranian pre-revolution films at MoMA, opening in the same month.

Iranian New Wave cinema emerged in the early 1960s in response to several cultural and political shifts. One major catalyst was growing dissatisfaction with filmfarsi, the dominant popular cinema of the period which relied heavily on melodrama, music, and dance, often drawing comparisons with Bollywood. These films typically centred on romantic and escapist narratives, themes that were increasingly curtailed following the 1979 Iranian Revolution after which conservative religious regulation intensified. There was however, also strong government-backed infrastructure for producing film, most notably the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Adolescents (Kanoon), which not only introduced young audiences to art for free, but also gave rare freedom and resources to the next generation of filmmakers such as Abbas Kiarostami and Amir Naderi. Under art director Firooz Shirvanloo—whose political leanings encouraged a cohort of left-wing writers and artists, until his dismissal in 1972—Kanoon helped support their ideas and launch their work and careers.

Like the French, Japanese, and Czechoslovak New Waves and Italian Neorealism, Iranian New Wave cinema engaged directly with social reality and political upheaval while addressing a global audience. Iranian cinema of the period was embedded in international modernist film culture: Nosrat Karimi’s popular satirical comedy The Carriage Driver (1971) was influenced by Italian neorealism through his work in Rome as an assistant to famed Italian film director and actor, Vittorio De Sica. The Postman draws on German playwright Georg Büchner’s 1836 play Woyzeck whilst also combining neorealist tropes with Luis Buñuel-esque surrealism. Bahram Beyzaie’s The Ballad of Tara (1979) is a feminist reworking of Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa 1950s samurai epics. As critic Hamid Dabashi argues, cinema enabled Iranians to be “re-born as global citizens in defiance of the tyranny of the time and the isolation of the space that sought to confine us.”

The season also hones in on women filmmakers in the Iranian New Wave. On the season’s opening night, The Barbican will screen the only surviving fragment of Marjan (1956), the first Iranian film directed by a woman, Shahla Riahi. “Without Riahi, we wouldn’t have the extraordinary women filmmakers working today,” Khoshbakht insists, including Rakhshān Banietemad, Samira Makhmalbaf, and Shirin Neshat. Only 24 years prior to Riahi’s Marjan, Roohangiz Saminejad became the first Iranian woman to appear in a sound film, The Lor Girl (1932), portraying Saminejad’s as an unveiled woman in public. After its release, Saminejad received so much public harassment and family pressure forced her out of acting entirely. She was forced to change her name and live in seclusion as documented in 1960. Yet despite backlash, the film contributed to broader modernisation, a process later reinforced by state reforms and increasingly reflected in Iranian cinema, which established the image of the modern Iranian woman.

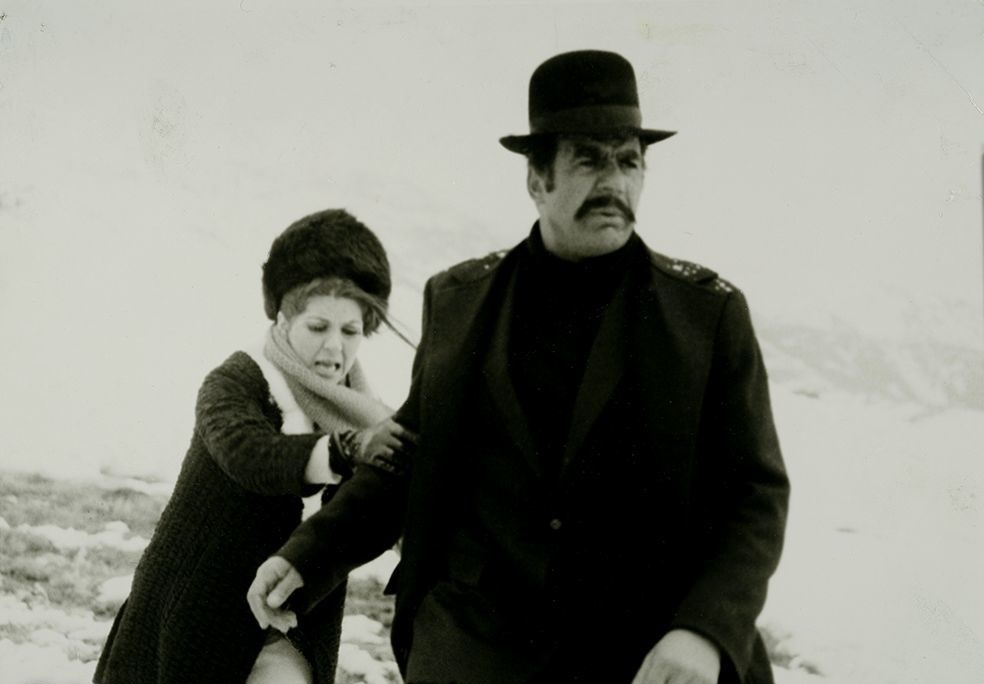

Marjan will be screened alongside The Ballad of Tara, a film completed during the Revolution and subsequently banned indefinitely. Khoshbakht remarks that “Iranians have never seen it in a cinema, which is extraordinary.” Shot in colour, it centres on a strikingly independent female protagonist in a rural village who becomes the object of desire for the ghost of a dead warrior. Marjan and The Ballad of Tara highlight the fragility of women’s authorship in Iranian cinema—both before and after the Revolution—while also challenging the restrictive ways women have been, and continue to be, perceived.

Dancer of the City, dir Shapour Gharib, 1970

One of the defining stylistic traits of Iranian New Wave cinema is the central role it assigns to the audience, with its heavy use of symbolism inviting interpretation. As Dr William Beeman, a professor who spent over eleven years in Iran studying arts and culture before the Revolution, explains in a documentary The Lost Cinema (2006): “Even when we have films that are rather political in nature, the basic ideals and morality of Iranian life are being emphasised. What seems to be defeat can actually be a victory as long as it’s a moral victory: the main character achieves this moral victory by refusing to sell out or refusing to yield to a superior power which is corrupt and illegitimate. Even in a situation where the character seems to be utterly devastated, the real redemption, the real hero in the film may in fact be the spectator, who becomes aware of the disparity between a corrupt superior power and a person who’s been victimised by that power.”

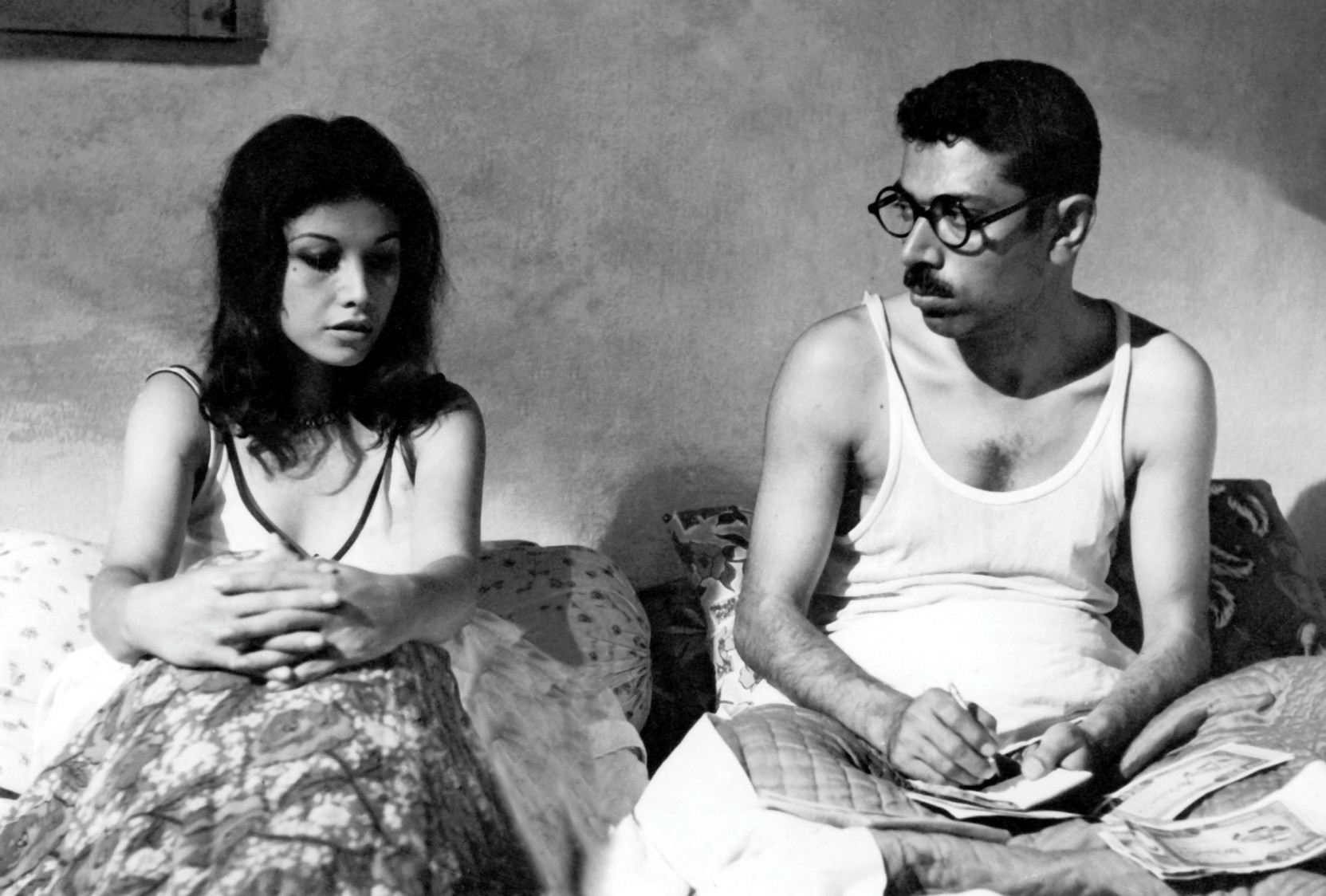

Take Masoud Kimiai’s The Deer (1974) as an example, described by Khoshbakht as “astonishingly militant, almost an invitation to armed struggle.” The film follows two former schoolmates reunited under desperate circumstances: one wounded and in hiding, the other a drug addict living in poverty. Their friendship reflects the social fallout of the White Revolution’s land reforms which started in 1963, and pushed large numbers of rural migrants into Iran’s industrial cities, where poor state planning left many unemployed, displaced, and vulnerable to drug use. Briefly released before being banned, The Deer was ultimately subjected to a forced alternative ending. At the Barbican, both endings are screened side by side, rendering censorship as structural violence enacted upon a film’s meaning.

It is crucial to distinguish pre-revolutionary censorship from the post-revolutionary censorship associated with Iran today. Before 1979, censorship was not governed by the moral codes that now dominate global perceptions of Iranian society. As Khoshbakht notes, “The absurd restrictions—of women veiled even in bedrooms, for instance—did not exist before the Revolution.” Women appeared unveiled in public life and on screen, though often at significant personal cost, as demonstrated by the harassment and forced withdrawal of early actresses like Roohangiz Saminejad. After the Revolution, censorship intensified and shifted decisively toward regulating women’s bodies and visibility, embedding moral control into law through the Iranian Constitution. Its ambiguously worded articles however, render censorship a subjective practice and dependent on individual bureaucratic interpretation. In response, filmmakers increasingly turned to symbolism, poetic language and allegory, a strategy that transformed restriction into a defining aesthetic of Iranian cinema. As Dr William Beeman observes, “The political cinema in Iran has a great deal of symbolism and symbolic layering in its construction, which gives it an artistic dimension that can be appreciated over and above the political dimensions of the film.”

“Some of the films in this programme have taken more than half a century to be seen in the way they were intended to be seen, or, in some cases, to be seen at all.”

Ehsan Khoshbakht on Masterpieces of Iranian New Wave Cinema

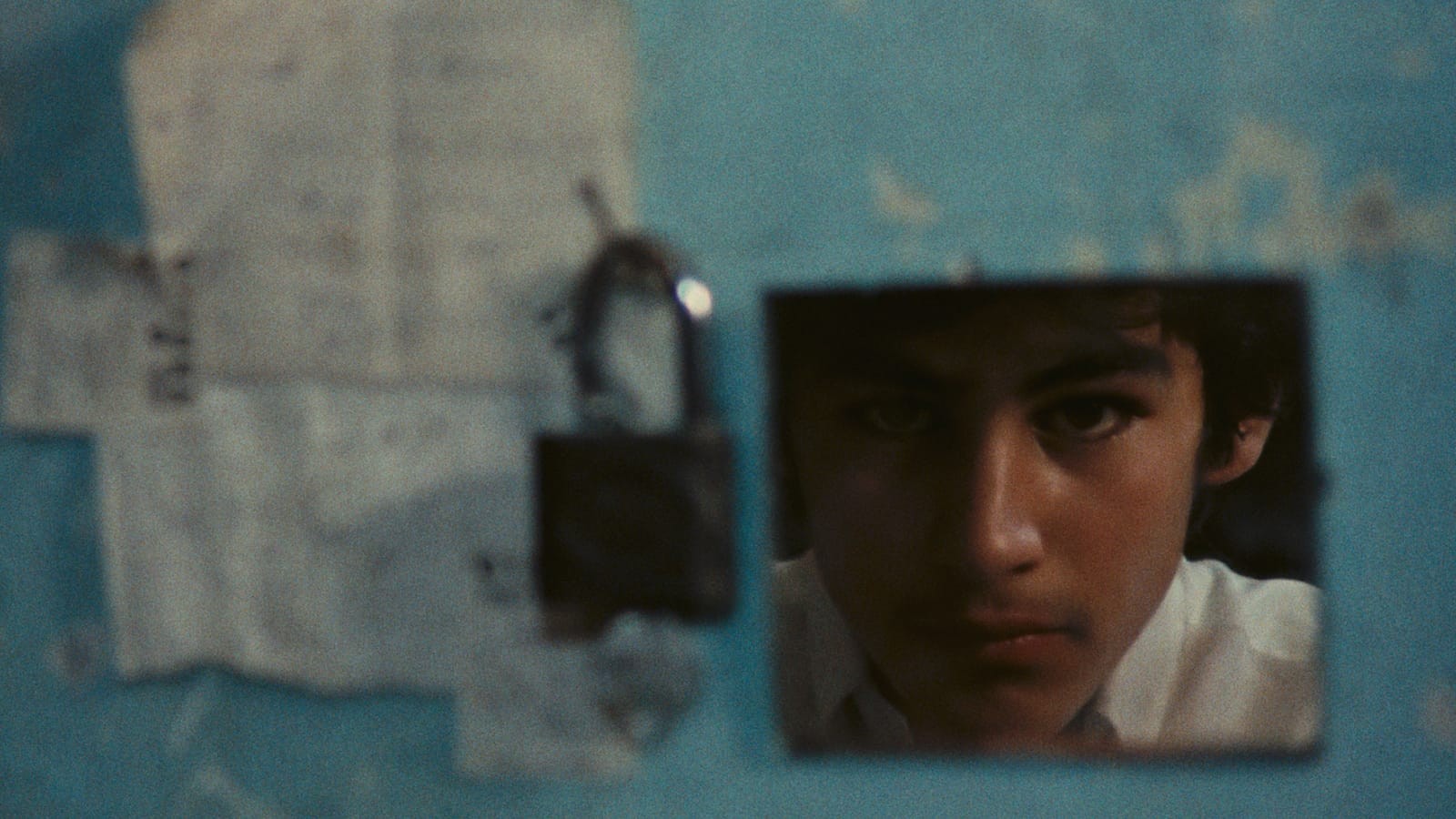

The programme itself is shaped by Khoshbakht’s work as a film restorer. Some of the films made in the period were lost or destroyed. A complete print of The Postman (1972) was only discovered last year at Arsenal Institute for Film and Video Art in Berlin and restored with support from Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation at Cineteca di Bologna. Screening at the Barbican on the 5 February, the narrative draws on Woyzeck by Büchner to weave satire, social realism, and symbolism into a bleak portrait of alienation and power. The programme closes on 26 February with the world premiere screening of Cineteca di Bologna’s newly restored Ebrahim Golestan’s Secrets of the Jinn Valley Treasure (1974). The restoration was made from an original camera negative discovered in Golestan’s house in East Sussex. “I was lucky.” Khoshbakht tells me. “It doesn’t happen every day that you find a camera negative in the director’s house.” In more recent history, filmmakers have continued to face restrictions. Under house arrest, Jafar Panahi co-directed This Is Not a Film in 2011 which was smuggled out of Iran on a USB drive hidden inside a cake. The film went on to receive international acclaim after screening at the Cannes Film Festival.

Despite the weight of Iran’s complex history over the past fifty years, Khoshbakht hopes audiences will not view these films solely as documents of repression. “I also hope they simply experience great cinema, regardless of the country of production.” Beautifully shot, bold and deeply empathetic, the films retain a striking immediacy, their humanist and avant-garde spirit undiminished by time. Rooted in an almost documentary realism, they favour real locations and ordinary lives, revealing how progressive Iranian cinema was in the 1960s and 70s and how deeply modernist these works remain. These films mattered not only because they existed against the odds, but because they helped shape global cinema, existing as both artistic triumphs and vital cultural records of their socio-political realities.