A few years ago, I was called to meet Bernardo Bertolucci. He had an idea and wanted to see if it could be a movie. The idea was this: One man. One woman. One house. The man we only see at night. The woman only during the day.

“Would you be interested in talking to him?” my agent asked me. He was laughing. The question couldn’t have been more rhetorical. With Bertolucci’s work, I built all my cosmogony as a teenager—my politics but also ideas of romance, beauty, composition, love. Poetry.

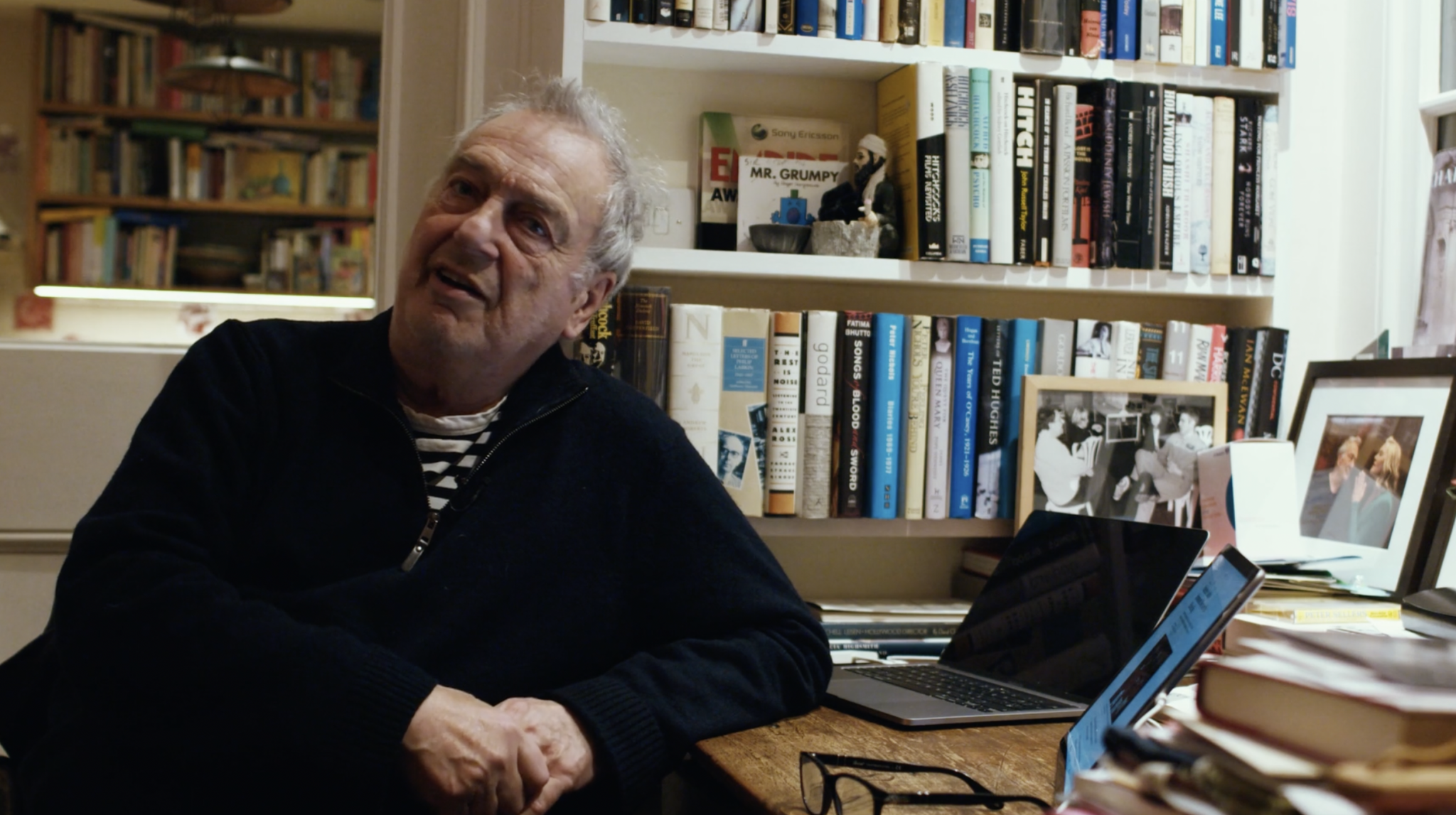

When I first entered his house in Rome, in via della Lungara, an elegant Indian gentleman greeted me as I sat down waiting in the blue and mustard living room. Immersed in all that beauty, surrounded by bookshelves full of videotapes, DVDs, movie posters, books, paintings, I tried—without succeeding—to meditate. To be calm and present. “Be here, at least now” I repeated to myself, “Stop being so anxious, fuck!” My thoughts frayed, I could not remember anything about anything. Not even how one talks to strangers, especially those who are so special. When Bernardo Bertolucci arrived, with his bruised body, and on a wheelchair, we sat facing each other. My heart was beating so fast I could feel it in my teeth. His smile, investigating me, was sweet but also mocking. He knew how agitated I was and it amused him.

While I tried to put together a few painful broken sentences, he talked to me about my last book, which he had read. He asked me what I had seen recently, then told me what he had just seen. I was unaccustomed both to the great masters and, not having a father in my life, to important men of that age asking me about myself and about life, and who were interested in hearing the answers.

I concentrated on his sweater to try to make everything easier. In particular, I chose to peek at a tiny stain on the wool, to make him more human. We drank coffee, his hands were shaking with disease, mine with fear. After a few minutes of shared tremor, he told me to come back the following day for breakfast. Together with my writing partner, Ludovica Rampoldi, from that day and for a year, I went back to his house, to write, talk, listen to music and to him. To drink espressos, bloody marys and to find a story, rummaging through all the possible stories that would appear. “Bring me two pages,” he told us every time.

And each time we brought two, four, then ten. A million.

I also began jotting down the story that, for me, was that of being with him, in that house, writing what we all knew was going to be his last movie. Maybe, I thought, we were there even if he knew that he was never going to make it to the set. We were there because his favourite thing of all was to write films, to imagine them. He knew that this was the sweetest way for him to spend his last months on earth. He perhaps thought that everything, even while disappearing, was going to be less painful if hours were spent in stories; in music that would accompany this last revolution. Choosing a soundtrack, writing dialogue on pain and disappearance, was in itself part of the ritual of disappearance, while his body slowly left him, while he slowly left his body, and life. Frame, then zoom out, so elegant and mastering this stunning camera movement too. I imagined all his helpers, his many friends, his family, his luminous and talented wife Clare People—all those who loved him—arranging for him, and with him, the best last round of dance. I imagined the backstage of the orchestration of our lunches, of the printed pages, the selection of the movies that were shown in the living room so that the three of us could be immersed in films, beauty, stories. “There is such an onslaught of the present,” he would say, “it leaves me exhausted.”

It was all a farewell waltz.

The onslaught of the present could be heard in his faint voice, in his beautiful struggle to refine, arrange, and shape this treatment, and then the script. To rally these characters too, follow them, make them disappear. From the treatment, which we read and re-read for months, he changed the tiniest details: ‘blue eyes’ into ‘light eyes’. He would file commas. Sculpt the solfeggio and the sound of the sentences. The entrances. The exits. “What are all these smiles in the script?” he would ask, when I read out loud.

And we took away all those smiles in the script.

He used to say, when cigarette ash fell on his shirt, that he was now his own ashtray. He lit more cigarettes, more ash fell on him, and the t-shirts replaced the sweaters with the arrival of summer. On the t-shirts too, I would concentrate on the little stains, or, by now, on how his t-shirts also spoke to me about him and us. Sometimes they had slogans from May ‘68 in Paris. On Godard. Scorsese. My favourite one had only the word California. It was blue. I saw California, then him in California. We laughed. We also cried.

I once cried as I re-read the script aloud.

“What are you doing, crying over something of yours?” he said.

“I thought I was crying over something of yours,” I replied.

Stealing his last little portion of wonder from everything, wrapping it up, possibly delivering it, was our calling, our happiness. It was crying for something that was ours, holding onto it tight, to then be able to let it go lightly. Never ours again, forever not ours again. His and Clare’s cats walked near us, on top of us, they knew everything about life and about the end. The same rays of sun warmed us all.

“I’ll close my eyes for a moment,” he would say.

And we either closed them with him and the cats, or typed lighter.

When I couldn’t be in Rome for a few weeks, he would complain. The sound of our being apart was that of his texts or the quick calls asking when I would be back. We spoke of movies, TV series. The Phantom Thread. Black Mirror. Maybe a piece at the theatre I’d seen in London, because Claire had suggested I should. Sometimes, we talked about food. What did you eat? What will we eat once together again? In England I ate the babaganoush he liked, from a grocery he liked, just so that I could write to him “I’m eating your babaganoush from Elgin Road”. When I returned to Rome, and the three of us went back to writing, to him and to our story, we also by now had our favourite recipes from his and his wife’s home. Sometimes, we would ask for a specific one we craved, and he was always happy to make us find it the following day. The salad was dressed in oriental style, the fried anchovies, and the macaroni with the tomato sauce was a little spicy. We always served ourselves twice. Sometimes three times. There was always dessert and fruit. Coffee and wine. We were so hungry. We said yes to everything.

Bernardo and I also went to the cinema together. We’d plan our own festival, his wheelchair parked near me. In the afternoon while it was raining outside, the room was all to ourselves and we thought that perhaps at the cinema, on planet earth, we were the only ones left. Given his age, and his role as a teacher and an immense man, before long I gave him a great role in my personal life beyond our work. Not having a father available, I might have too quickly given the role I had on hand for the auditions of that age. At the summons for the part, he arrived, smiling and loving and generous, and I threw open the door. I thought “Here you are!” Partly because I like to swing the doors wide open, saying “Here you are!” I like melodrama, crying, reassigning roles, and celebrating them. And partly because the role really belonged to him. He often asked me about me and about life, what I thought, and how I was. He told me if what I wrote made sense, if it was good. He wanted me near. And for me to do better, write better, fix something again. Then, once again. He cared. Had I travelled well? Was I tired? Was it raining in London? Was my child all right? After all, he had not been a father in his lifetime.

“We were so many children, we had been so for so long, that maybe it was impossible for both of us to be able to accept becoming fathers,” he once said about him and his brother Giuseppe. “This thing of extinction is very interesting,” he also said.

Even when he got a bit mad, maybe because I had to go away again, I understood him completely. And when he got offended if I was gone for too long I knew he was right. That time was so precious, how could I do anything else? How could I waste it? He was right and I now regret every single time I have left that room. Him. He knew I would one day. The only thing we were asked was not to depart from the adventure of creating together. Not to leave that story, and the marathon needed to reach it. To help each other keep the portal open, be magnets for the matter that was to land.

“I didn’t know you were so busy,” he’d say. “When will we write again?”

Mixing our voices with that of Bernardo’s felt like a miraculous act of love, beauty, and life. The sound of our own voice would disappear, leaving space for a shared one, and a shared brain, and body. With this one shared body we’d breathe big and write more and laugh loud and see better. It was a ceremony. “I had a very Kafkian dream: I was a beetle,” he laughed one morning. “Does this mean it’s the end?”

Looking for an end together, looking for the end together, was also a ceremony—a sacred one—and like every ceremony, it had its rituals, its prayers. Its grammar of torment and liberation. The search for the end of our story coincided with the search for the end of his earthly life.

“In films, I leave the end open because that’s how life is,” he always said. For an open ending in both the film, and for his life, we tried several. Until both for the film, and his life, the end came. Our times were ripe together. We typed the end, whispered the end, read it aloud, and lay it down for the night.